Well, that’s it. A project that I expected to complete within a few months ended up dragging out over the course of just about three years. In that time, I’ve written about little else here on Hoxsie – it’s been Albany in 1886 for quite some time. When information was sparse, when the stories were hard to tell, when there just wasn’t much at all to say, some of these entries really took time. (I’ve also been busy with other projects. No regrets.)

I’ve truly been heartened by the interest in and support for this project, including a number of folks who have contributed photographs, additional research, and gentle corrections. We found a few markers that I was unable to locate on my own and confirmed the absence of others.

This all started with trying to find out about a marker that was never placed, the Burdett-Coutts marker that should have celebrated the contributions of Black residents of Albany, and which “mysteriously” never was placed in Washington Park as planned. Then I started in on the rest of the markers. The Bi-Centennial Committee named 40 markers in its official publication, but we know that at least 47 were cast.

The discrepancy’s a bit of a mystery. The official publication that we have relied on throughout this series, “Albany Bi-centennial: Historical Memoirs,” by A. Bleecker Banks, chair of the Bi-Centennial Printing Committee, wasn’t published until two years after the bicentennial itself. In July 1888, the Argus complained that the promise of “an elaborately compiled, illustrated, adorned masterpiece of the printers’, engravers’ and artists’ handiwork” had not yet been produced. “This wonderful production – for wonderful it should be considering the time it has taken to collate its contents, assuming they have been collated – still ‘hangs fire.’” The Argus sarcastically hoped the book might be presented “sometime during the present century.” All the more odd – or perhaps it was sarcasm in return – that Banks opened the publication with a preface that said, “It was only necessary to follow the different statements of the Albany daily newspapers to make the compilation of the facts and give the data of Albany’s Bi-Centennary Celebration.”

The text itself makes no mention of time having passed before the publication came to fruition, nor does it explain the differences between the text for the bicentennial tablets as presented by the committee and how they finally appeared. Nor does it account for the at least seven tablets that weren’t listed in the official program – at least some of which carried a date of 1886 and thus should have been included in the publication two years later.

What the markers were about

Of the 47 tablets:

- Only twenty-one remain, though a number of those have been moved from their original locations, and two of those are replacements. That’s not a terrible survival rate, because some of the ones that remain have seen some terrible neglect, especially the ones that reside within sidewalks.

- Six denote churches – Old Dutch Church, Lutheran Church, First English Church, Old St. Mary’s, First Presbyterian Church, First Methodist Church – and one denotes a more generic “Jewish Congregations.” Despite the prominent role of Black churches in abolitionism in Albany, the Bicentennial Committee didn’t choose to recognize any African-American churches or congregations.

- Eight denote specific people: First Patroon, Philip Livingston, George Washington, John Shutte, Johannes Van Rensselaer (on the Crailo marker), Joel Munsell, Anneke Janse Bogardus, and Joseph Henry.

- Eleven denote specific (non-church) buildings: Fort Orange, Schuyler Mansion, Oldest Building in Albany, First Theatre, Manor House, Municipal, Fort Frederick, Old Capitol, VanderHeyden Palace, the Old Lansing House, and Crailo. Of those, only the Schuyler Mansion and Crailo (which isn’t in Albany) still stand.

- Thirteen recognize individual streets: Washington Avenue, Hamilton Street, Dean Street, State Street, Norton Street, Franklin Street, Broadway, James Street, Eagle Street, Exchange Street, Clinton Avenue, Monroe Street, and Madison Avenue.

- Six recognize places around town: Old Elm Tree Corner, City Gate, Lydius Corner, North-West Gate, South-East Gate, Academy Park.

- Two recognize forgotten streams: Foxen Kill and Beaver Kill,

- Only two recognize some kind of event: Washington’s Visit and the Bicentennial Loan Exhibition.

What the markers weren’t about

In that festival of commemoration, only one woman, Anneke Janse Bogardus, is ever mentioned, and it’s for her fortune and property. There isn’t a Black person or institution memorialized – not even a Black church. Yet, several slaveholders were recognized with markers.

No industry or business is favored, either. As noted above, only two were about particular events – even given the extensive amount of history that has happened here.

The makers of the markers

Very little has been written through the years about the men who made these markers.

The patterns – the designs themselves – were the work of William Hailes Sr. The Bi-Centennial Committee didn’t ever credit him, but many of the markers bear the legend “W. Hailes Fecit,” meaning “William Hailes made this.”

Hailes was foreman of the pattern shop at Rathbone, Sard & Co., the stove manufacturers, for many years, later running his own business as a pattern maker on the third floor of a major building at Hamilton and Broadway for 20 years before his death. His 1892 obituary makes no mention of the bicentennial markers, but it does give us some of his story.

Born in Portsmouth, England in 1824, he came to America with wife and daughter at the age of 24 and settled in Albany, where he remained. “He was a natural inventor and had received many patents, notably those involving the construction of stoves and car wheels.” (In fact, we found 20 patents under his name, mostly involving stoves, from 1862-1894.) He listed himself as a pattern maker in some censuses and directories; in 1870 he gave his occupation as “inventor.” His pattern workshop, at least in 1875, was on the third floor of 15 Hamilton Street, a building that was either part of or just directly behind the still-standing (but condemned) Four E-Comm Square on Broadway. His home that same year was 197 Hamilton, toward the western end of the block between Eagle and High, a block entirely wiped out by the construction of the Empire State Plaza. He died of valvular heart disease at age 68 at Van Wies Point in Bethlehem, and is buried at Albany Rural Cemetery.

The Albany Argus reported in 1914 that there is extensive wording on the back side of each of the tablets:

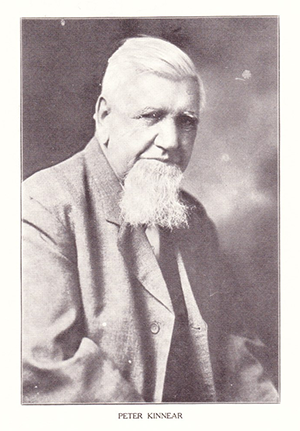

“The property of the City of Albany, N.Y. To Be Kept Perpetually on This Site. Peter Kinnear founder. Monumental Committee, Walter Dickson, Charles Edmond Jones, Samuel Bartow Towner, Leonard Kipp, Wheeler Blinn Melius, George Rogers Howell, Harmon Pumpelly Read.”

We haven’t observed the back of a tablet so cannot confirm that, but other sources also indicate the casting was done by the foundry of Peter Kinnear.

Peter Kinnear is a much more familiar name to Albany history buffs. His 1913 obituary said “he was in every movement that tended to better the city and his time and his money were always ready to aid any worthy cause.” He was born in 1822 in Forfarshire (now Angus), Scotland, apprenticed as a machinist at the age of 10, and worked in Belfast, Manchester and Liverpool before coming to Ontario in 1847. He then worked in New York before settling in Albany, working in Orr’s brass foundry, later Orr & Blair, which eventually became Blair & Kinnear.

He is also noted for his role as a backer of the Hyatt brothers – John Wesley Hyatt developed celluloid and a commercial use for it in billiard balls; brother Isaiah put the substance to use in the Albany Embossing Company, maker of dominoes, checkers and other game pieces. It’s curious that Kinnear’s obituary says “the first corporation formed to manufacture celluloid was aided by Mr. Kinnear because of his faith in the inventor, Isaiah S. Hyatt,” – it was John who did the inventing. Eventually Kinnear, then of the firm of McElroy and Kinnear at 68 Beaver Street, gained control of the billiard ball business, forming the Albany Billiard Ball Co. The Pruyn family got hold of the embossing company, and both had their hands in yet another celluloid venture, The Bonsilate Company.

Kinnear’s obituary noted that despite being 91 years old, until 10 days before his death he “had been attending to his business as head of the Albany Billiard Ball Co., going out to the Delaware avenue plant daily.” He was also a prominent member of the St. Andrew’s Society, president for nearly 14 years, and instrumental in the creation of the Robert Burns statue in Washington Park.

I’ve found all of this so very interesting, thank you for all of your efforts to bring this Albany history lesson to us. I’m anxious to know what you’ll begin looking into next!

Thanks, Lisa! I think I’m just going back to random, short things – whatever strikes me as interesting. I’ve had a long list built over over the past few years.