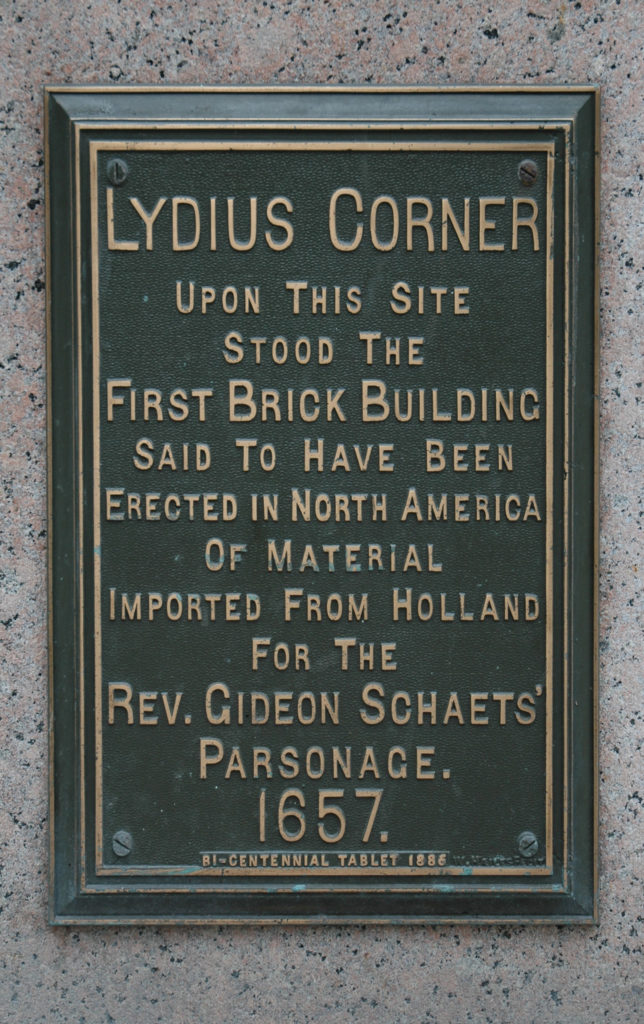

After a long hiatus (in part brought on by life in general, in part brought on by a major hack of our websites that needed cleaning up), we’re back to our histories of the tablets placed around Albany in celebration of the city’s charter bicentennial in 1886. This one marks the Lydius Corner, perhaps also known as Dexter Corner, and now more plainly as the northeast corner of State and Pearl.

The text described by the Bi-Centennial Committee differs just a tiny bit from the finished marker:

On north-east corner of State and North Pearl streets – Bronze tablet, 16×22 inches, inserted in Pearl street wall. Inscription: “Upon this Site Stood the First Brick Building said to have been Erected in North America. Of Material Imported from Holland for the Rev. Gideon Schaet’s Parsonage.”

This one still exists! It’s right down at sidewalk level next to the State Street entrance to the Subway sandwich shop, in what we guess is now called the Bank of America building:

Dominie Gideon Schaets

According to Stefan Bielinski at the New York State Museum, Gideon Schaets was born around 1607 in Holland; he and his wife Agnietje were teachers who ran a small school. He was later ordained in the Dutch Reformed Church, and came to Rensselaerswyck and Beverwyck to replace Dominie Johannes Megapolensis in 1652. His wife Agnietje appears not to have come with him, although at least one child did, or at least eventually joined him. He lived until 1694, and was buried beneath the Dutch Church.

Schaets (or Schaats, among other spellings) had a colorful tenure. In 1676, he got into a tussle with his church’s Consistory, not for the first or last time, and charged Dominie Renselaer (also given as Renzelaar, in our favorite variant spelling of Rensselaer ever) of false preaching, which Renselaer declared a “false lie.”

In 1679/80, he got into a tussle with Albany Lutherans. According to O’Callaghan’s “The Documentary History of the State of New York,” Schaets complained that Myndert Frederickse Smitt came to his house and told Schaets “never to presume to speak to any of his Children on religious matters, and that he the Dom[inie] went sneaking through all the houses like the Devil,” adding that their Lutheran minister didn’t do such things. Schaets also complained that Myndert’s wife was said to have “grievously abused & calumniated [Schaets] behind his back at Gabriel Thomson’s house, as an old Rogue, Sneak &ca. and that if she had him by the pate, she should drag his grey hairs out of it.” For her part, Myndert’s wife Pietertje denied saying that, but said that Schaets had called her religion a “Devilish Religion.” In the end it appears that Myndert and wife acknowledged the Dominie “in open Court to be an honest man, and that they know nought of him except all honour & virtue and are willing to bear all the costs hereof,” which costs were six beaver pelts and six “cans” of wine.

The house in which he lived appears to have been owned by the Reformed Church, as Schaets and the Consistory in 1679 “freely without any persuasion promise to convey and give a proper Deed of the house occupied at present by Dom: Gideon Schaets to be for the future a residence for the Minister of Albany for the benefit of the Congregation of the Reformed Church here; as the house was built out of the Poor’s money and now being decayed, the W: Court promises to repair said house and keep it in good order fit for a Minister for which purpose it shall be conveyed.” In 1680, the Consistory consented to contribute “the sum of one thousand guilders Zewant, for the reparation of the said house.”

There is no mention then of the house being the first brick house in North America, and the claim seems unsupported. There is mention in a 1900 article that the wooden beams may have come from Holland, but not the bricks themselves. It’s often said that the bricks were used as ballast in ships, and that that was the source for some of the earliest bricks in North America, but we find no other details of this particular building’s construction.

The Trouble With Anneke

In 1681, Schaets got into hot water with his own congregation again, possibly over the behavior and reputation of his daughter, Anneke Schaets. According to a profile at geni.com, Anneke had an affair with none other than Schenectady founder Arendt Van Curler in 1663, prior to her marriage to someone else, and that year bore a child named Benoni Arentsen Van Curler (or Corlaer), Jr.

Anneke later married a sloop captain named Thomas Davidse Kikebel, who lived in Manhattan. The couple appears not to have gotten along, nor to have lived together much; she lived mostly with Dominie Schaets.

This caused an amount of dissension in the church that appears to have gone on for decades, with some women refusing to attend church if Anneke were present. In 1681, there was an Extraordinary Court session held at the request of the elders and deacons of the church because Gideon Schaets refused to “visit them for the purposes of holding religious meetings in the Church.” Anneke had previously agreed she would “willingly [ ] absent herself the next time from the Holy Table of the Lord . . . as it was her duty, so as to prevent as much as possible all scandals in Christ’s flock.” The elders asked the court to call Schaets into court; the court sent a messenger (“the Bode”), twice, and twice Schaets refused to appear. On a third visit, the Bode found Anneke, who told him, “Mine Father will not come; they may do what they please, for the magistrates are wishing to make me out a W[hore].

The magistrates then sent constable Jacob Sanders with a special warrant:

“Who having visited the house and being unable to find him the constable then asked his Daughter, Anneke Schaets, where her father was? She answered–Know you not what Cain said? Is he his Brother’s keeper? Am I my father’s keeper? Whereupon the constable told her that she should let him bring him. To which she answered, she had nobody for him to bring, and had she a dog, she would not allow him to be used by the Magistrates for such a service. The Magistrates had their own Bode.”

Schaets was found and finally agreed to appear before the magistrates so long as the church leaders (the “consistory”) were not present. It ultimately resulted in an agreement that Anneke would be sent to her husband Thomas in New York, on June 9, but “as she was so headstrong and would not depart without the Sheriff & Constable’s interference, her disobedience was annexed to the letter” that would recommend her to the officials in New York.

The couple soon returned to Albany to settle their affairs, and the court was recommended to try to reconcile them. The court took this on, and it seems the couple agreed they could get along as long as two men watched over Kekebel’s conduct at all times. On July 29, 1681, the court wrote that:

“Tho: Davidtse promises to conduct himself well & honorably towards his wife Anneke Schaets; to love & never neglect her but faithfully and properly to maintain and support her with her children according to his means, hereby making null and void all questions that have occurred and transpired between them both, never to repeat them, but are entirely reconciled; and for better assurance of his real Intention and good resolution to observe the same, he requests that two good men be named to oversee his conduct at N. York towards his said wife, being entirely disposed and inclined to live honourably & well with her as a Christian man ought, subjecting himself willingly to the rule and censure of the said men.

“On the other hand his wife Anneke Schaets promises also to conduct herself quietly & well and to accompany him to N. York with her children & property here, not to leave him any more but to serve and help him and with him to share the sweets and the sours as becomes a Christian spouse; Requesting that all differences which had ever existed between them both may be hereby quashed and brought no more to light or cast up, as she on her side is heartily disposed to.

“Their Worship, of the court Recommend parties on both sides to observe strictly their Reconciliation now made, and the gentlemen at N. York will be informed that the matter is so far arranged.”

In 1685, Dominie Schaets was regarded as “very feeble,” but he outlived a second wife, who bequeathed a house to him in 1688. He lived on until 1694, having served the Albany church for about 42 years, and was buried beneath the church. We’ve talked before about what happened to those burials.

The Lydius of Lydius Corner

So the corner was noted as the home of Gideon Schaets, but named for a Lydius. First was Johannes Lydius, born in Maesden, South Holland, the eldest son of Rev. Hendricus Lydius (all this, again, courtesy of Stefan Bielinski). Lydius became dominie of the Reformed Church of Antwerp, Belgium, by 1692, but he, too, had problems with his congregation, which led him to accept a call to minister the Dutch Church at Albany, arriving in 1700. “New improvements were made on the domine’s house, and a new turned bedstead was purchased for Dom. Lydius at 40g[uilders].” (Munsell, Collections on the History of Albany, 1865) He also ministered to Schenectady’s church from 1705-1709. While his age is never exactly clear, he was somewhere in middle age when he fell ill in 1709; he wrote a will that noted he was “sick in body” in September of that year, and died in Albany on March 1, 1710.

By the way, we do presume, but haven’t any evidence at the moment, that old Lydius Street was named in honor of the Dominie Johannes Lydius. The street was renamed to Madison Avenue, apparently after 1863 (when we still find real estate listings on Lydius).

His son, Colonel John Henry Lydius, lived on in the house, as did John Henry’s son Balthazar. Apparently it was Balthazar for whom the corner was eventually given the long-lasting epithet Lydius Corner.

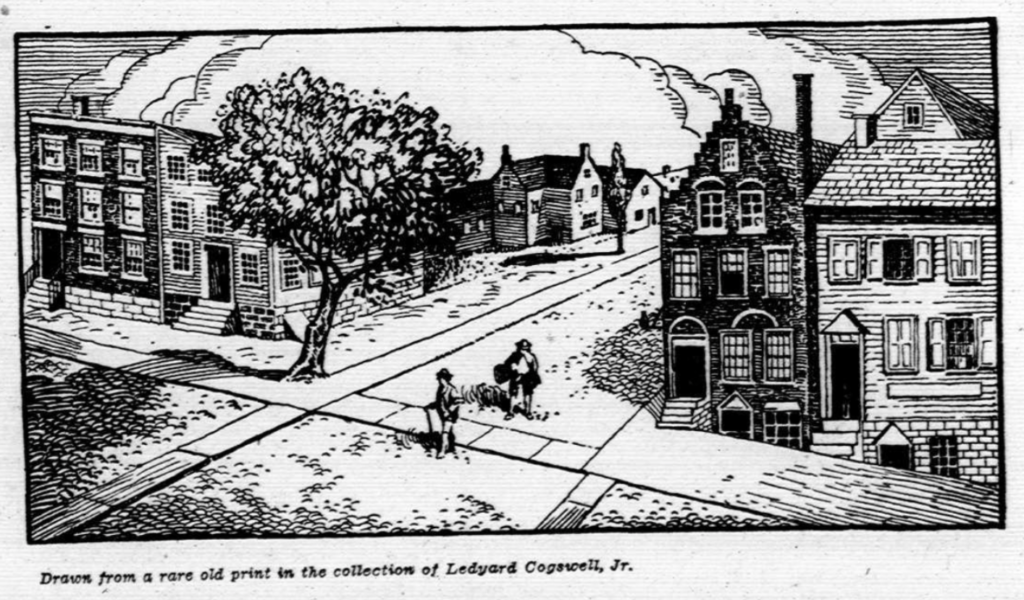

An article in the Argus in 1901 cites “memories and incidents of interest” around the old Lydius corner, the northeast corner of State and Pearl. “The lot, originally patented to Jan Thomase in 1664, successively passed to the possession of Cornelis Steenwyck, Jochem Staats and Jacob Tysse Vanderheyden. In 1679 Peter Schuyler occupied a house on this lot. From 1657 until its demolition in 1833 the corner was occupied by a two-story and attic brick building, with a terraced gable, after the prevailing Dutch style. The gable faced State street and contained the main and basement entrances. The Lydius house, when it was razed, was believed to be the oldest brick building in the United States. The building finally passed into the possession of Colonel John Henry Lydius, son of Dominie Johannes Lydius. Colonel Lydius left America in 1776, and died near London in 1791.”

An Argus article in 1900 says, “Colonel Lydius was a man of great ability and intrepidity, but was imperious and unscrupulous. Serious charges were brought against him in 1747 by the council of the province, for abjuring his Protestant religion in Canada, of marrying a woman there of the Roman faith; and of alienating the friendship of the Indians from the English. Colonel Lydius died in Kensington, near London, in 1791, having retired to England in 1776.”

Balthazar Lydius, Terror to All The Boys

The Argus continues: “The old house descended to his son, Balthazar, who lived there unmarried for many years. He was an eccentric old bachelor and during the early years of the last century was a terror to all the boys of the city. It is said that late in life he married an Indian squaw. The present building, erected in 1832, was for many years known as Apothecaries’ hall.”

An article in the Argus in 1903 focusing on the ‘Plan of a Survey of State Street Albany Made in 1792 by John Bogert” says that

“The Lydius corner . . . was occupied at the time of the survey by a very eccentric old gentleman, Balthazar Lydius. He died on the 17th of November, 1815, aged 78, and was the last male descendant of his family, which was ancient and respectable. The house in which he lived was supposed by many to have been imported from Holland; bricks, woodwork, tiles and ornamental irons, with which it was profusely adorned, expressly for the use of the Rev. Gideon Schaets, who arrived in 1652. The materiale [sic] for the house arrived simultaneously with the old bell and pulpit, 1657. It was supposed to be the oldest brick building in North America at the time of its removal in 1832.”

A 1900 article in the Argus (one of a series of “Historical Fragments” written by “Jed”) also wrote about the Lydius corner. It says the lot in 1664 was described as 69 feet wide on Pearl street and 30 feet on Jonker (later State) when it was patented to Jan Thomase (Mingael).

“The records do not show who the previous owner or occupant was. It passed through the hands of Steenwyck, Staats and Vanderheyden in short order, and a house on the lot was occupied by Pieter Schuyler in 1679. There may have been more than one house on the lot. The 1657 house built for Gideon Schaets was later known as the Lydius house.

“In 1821 the old house was altered somewhat in order to accommodate the upper rooms to the purposes of a printing office for Cantine & Leake, State printers, and during the progress of the work a pewter plate was found attached to one of the timbers which disclosed the fact that the beams which supported the floor were brought from Holland for the building of the Dutch church, but were found to be too short and were used in the construction of this building. The church was built in 1656, the cornerstone being laid on June 2 of that year by Rutger Jacobsen with great ceremony, which would seem to establish the date of the erection of the old house, which must have closely followed the building of the new church.”

The article then focuses on Balthazar, repeating the description of him as the terror of all the boys of the city, and more:

“Strange stories, almost as dreadful as those which cluster around the name of Bluebeard, were told of his fierceness on some occasions; and the urchins, when they saw him in the streets, would give him the whole sidewalk, for he made them think of the ogre growling out his ‘Fee fo, fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman.’ He was a tall, thin Dutchman, with a bullet head, sprinkled with thin white hairs in his later years. He was fond of his pipe and bottle, and gloried in celibacy until his life was in the ‘sere and yellow leaf.’ Then he gave a pint of gin for a squaw, and calling her his wife, he lived with her as such until his death, in 1815.”

Another story says that Lydius “bought a white woman named Letty Palmer for a bottle of rum, a pound of tobacco and a silver dollar. The husband repented of his bargain, and called on Letty, but was met by Balthazar, who soundly horsewhipped him for his interference.”

The article also cites an unnamed writer who had occasion to visit the Lydius house as a youth. “To my eyes it appeared like a palace, and I thought the pewter plates in a corner cupboard were solid silver, they glittered so. The partitions were made of mahogany and the exposed beams were ornamented with carvings in high relief, representing the vine and fruit of the grape. To show the relief more perfectly, the beams were painted white.”

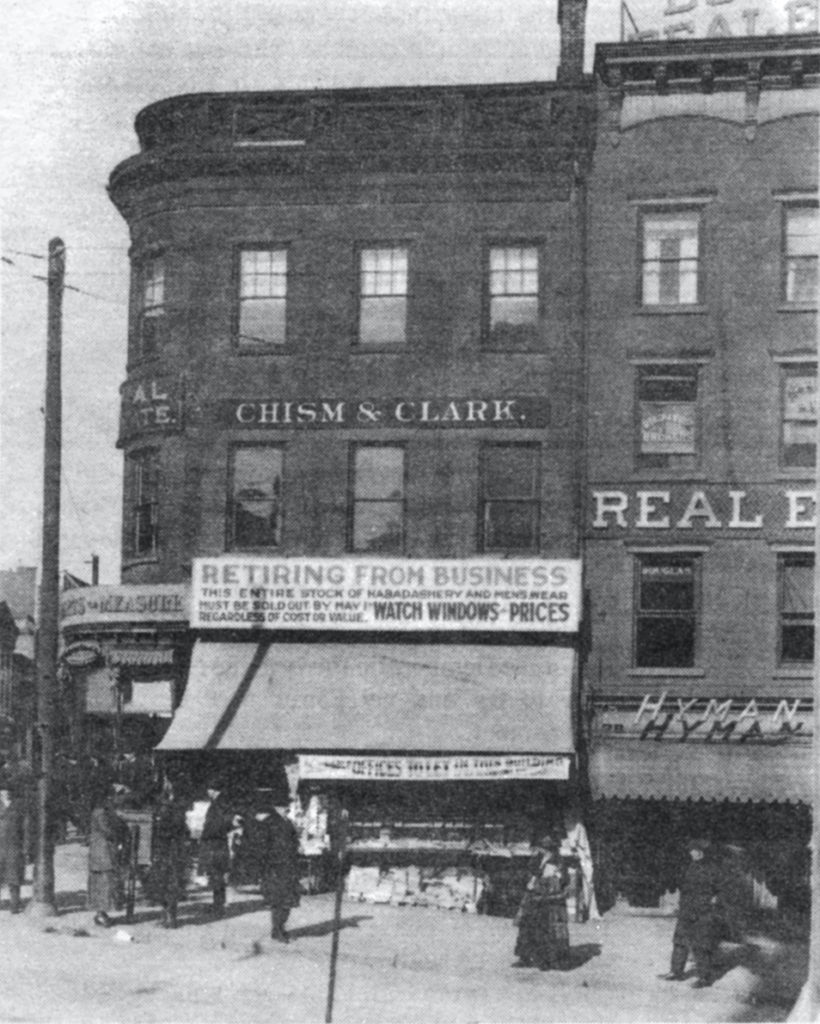

Apothecaries Hall

The lot and buildings were put up for sale at public auction in 1828. The Lydius house was torn down in 1832 by James and George Dexter, who built the building that was then known as Apothecaries’ (or Apothecary) Hall. James was a land agent (in 1860, anyway) and George was a druggist; they were brothers who lived together; George’s daughters also lived with them, as well as several servants, in 1860. James died in 1867. George, who then lived at 113 State Street, died in 1883, at age 83.

Apothecaries’ Hall operated for some time, and seems to have attracted druggists (there were ads for leases that included the “philosophical apparatus,” which means scientific equipment, in the 1870s). George Dexter seems to have operated some form of apothecary there through at least 1849, selling every cure-all imaginable. Following that, it went by the name of Dexter & Nellegar’s.

In 1875, though it was reported that “Mr. Olcott is looking for a site for his new bank,” and that George Dexter was asking $75,000 for the Apothecary Hall site. (The Olcott family of Ten Broeck Mansion fame were long connected with the Mechanics & Farmers Bank.) Olcott ended up choosing a site below James Street, and Apothecary Hall continued for another half a century.

An 1895 Times-Union article reported that “The best paying property in Albany is said to be the old Apothecary hall on the corner of State and Pearl streets, so long run by Dexter & Nelligar [sic]. It is now owned by a daughter of Mr. George Dexter, and returns to its owner over 30 per cent on its valuation.”

New York State Bank

The site was redeveloped in 1926-1927, when the New York State Bank decided to build a very large new office tower, designed by Henry Ives Cobb. The most famous thing about this building, now approaching its own century mark holding down the Lydius Corner, is that it incorporated part of the facade of the bank’s Philip Hooker-designed building, which was moved carefully up the street, into its own center facade. The building now houses the Bank of America. And we were happy to find that when it was built, the bicentennial marker survived.