Our last entry talked about the Albany Bicentennial celebration and the fate of a marker meant to commemorate the Black citizens of Albany that may never have gotten to its intended location in Washington Park.

Now let’s talk about the bicentennial markers that did make it to their intended locations (mostly). We know what all of them said because they were recorded in the historical memoirs of the Albany Bicentennial written by Mayor A. Bleecker Banks.

As part of that elaborate week of celebrations in 1886, there was a Committee on Monumenting and Decorations, chaired by Walter Dickson, and including Charles E. Jones and Samuel B. Towner, as well as members of the celebration’s advisory committee. The committee was originally the Committee on Decorations, “to have charge of same and of monumenting the city if deemed advisable.”

And they deemed monumenting the city very advisable indeed. In May 1886, Dickson presented a detailed report on behalf of the committee, which provided for “four evergreen arches; nineteen granite slabs with bronze tablets; five bronze tablets in buildings; five bronze tablets, old street names; decorations for the City Hall, City building, Schuyler corner, Pemberton corner, Schuyler mansion, Manor house, Albany; Manor house, Greenbush, and other ancient houses.”

The evergreen arches were to be placed at each place designated as the city gates of 1695. The committee took its work seriously:

“Your committee, aware of the grave responsibility to them entrusted, of monumenting the site of old land marks and cherished spots which are intended to add to the attractiveness of the city of Albany, and which will, doubtless, arouse in the hearts of unborn generations a stronger love of birthplace and home, and a more deeply impressed familiarity with its early history and its prominence in securing the liberties he, as a native, now enjoys….”

Not wrong, Committee on Monumenting and Decoration; you were not wrong.

They presented their intended bronze tablets on June 10, 1886. To the best of our knowledge, they were all cast (though often with changes to the text), and most were placed as indicated in the Banks book. For the next little while, we’re going to highlight each of these, providing a photo and current location where possible, so that we may arouse in your hearts a stronger love of birthplace and home. We’ll use the order that was used by Banks; the numbering of the tablets appears somewhat arbitrary but gives us a reference.

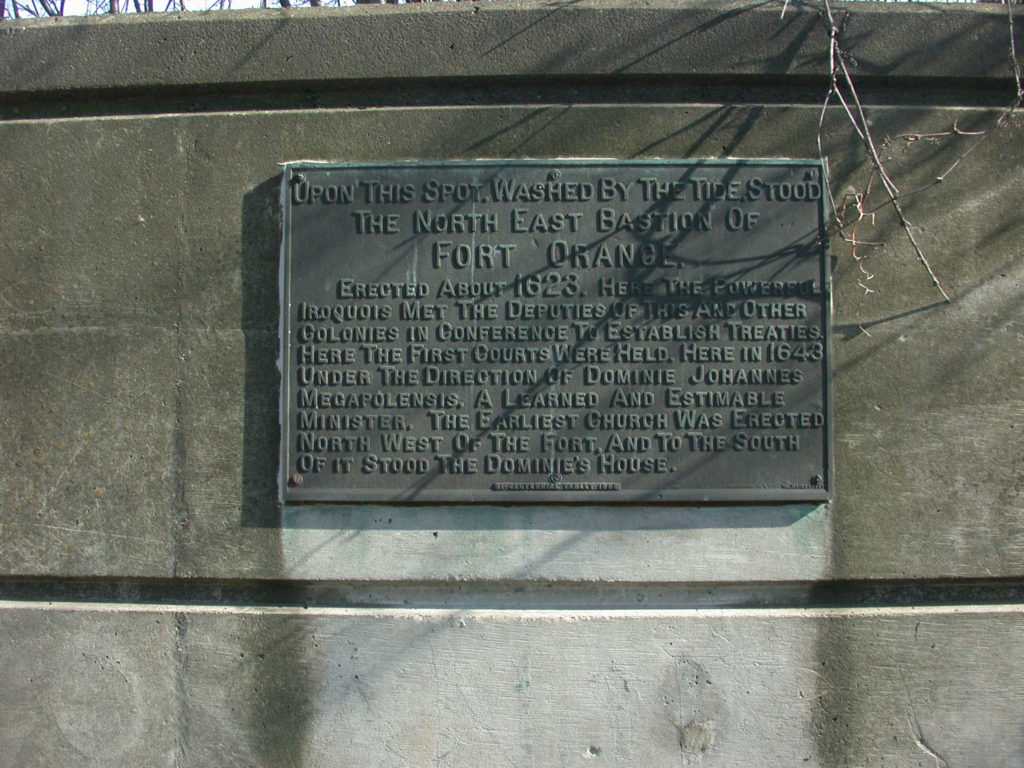

Happily, the first tablet in the list, Tablet No. 1 – Fort Orange, still exists. The committee described it thus:

Tablet No. 1 —Fort Orange

Located fifty feet east of the bend in Broadway, at Steamboat square, will be placed a granite block 3×4 feet square and sixteen inches high, with a slanting top to shed water and surrounded by an iron railing for protection. On the top of this granite will be placed a bronze tablet 20×32 inches, with raised letters on stippled ground-work fastened with flush bolts. On it will be inscribed:

“Upon this Spot, Washed by the Tide, Stood the north-east Bastion of Fort Orange, Erected about 1623. Here the Powerful Iroquois met the Deputies of this and Other Colonies in Conference, to Establish Treaties. Here the first Courts were Held. Here, in 1643, under the Direction of Dominie Johannes Megapolensis, a Learned and Estimable Minister, the Earliest Church was Erected North West of the Fort, and to the South of it Stood the Dominie’s House.”

Fort Orange, which was a fur trading post established in 1624 (according to more recent research), was completely distinct from the community of settlers established in Rensselaerswijck under the Patroon, and in fact there was plenty of friction between Kiliaen Van Rensselaer and the Dutch West India Company (you can read about it here), which owned the fort. Pieter Stuyvesant did about all he could to discourage settlement around the fort. This distinction is why some of us get a little incensed when people say Albany was originally Fort Orange. Not exactly. (There’s more on Fort Orange at the New Netherland Institute site.) A major power struggle between the Patroon’s agent and Stuyvesant culminated in the West India Company seizing the little village in 1654 and proclaiming it Beverwijck. (I’m being inconsistent with the spellings. It’s fine.) So it would be more true to say that what became Albany began in spite of Fort Orange, not as an outgrowth of it. True spite.

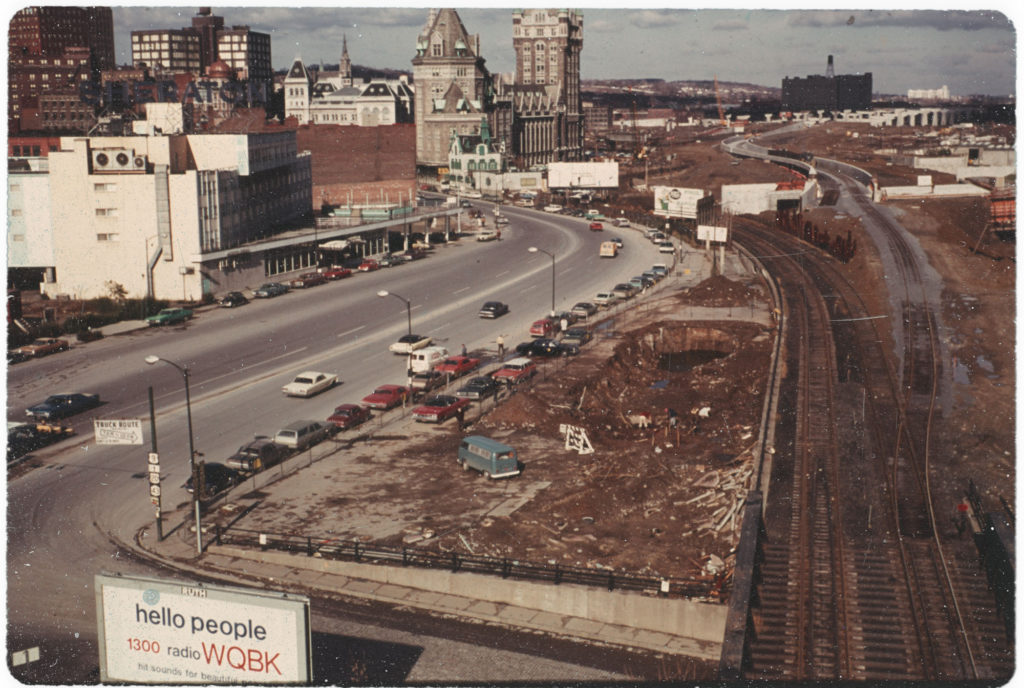

As we said, this one still exists, but you have to be an observant pedestrian (or a seriously distracted driver) to find it. It is currently attached to a wall along a sidewalk underneath one of the high flyovers to the Empire State Plaza, on Broadway between Pruyn Street and Madison, in a bleak no-man’s land. Not a terribly fitting representation for Tablet No. 1, but it’s a miracle that it not only survived, but was properly placed in construction when all that mess was created back in the ’60s and ’70s. We’re grateful it survives, though its granite block and protective iron railing are, of course, lost to history.

Dominie Megapolensis was one of the more important early Albany figures. The State Museum’s Stefan Bielinski notes that he brought his family to New Netherlands in 1642, and came to Rensselaerswyck shortly thereafter (Albany historian Joel Munsell said he came here August 11, 1642). He originally lived in Greenbush and preached at his home there, but then the Patroon’s storehouse near Fort Orange was adapted into the first Dutch church. Megapolensis served until 1649, when he moved to New Amsterdam.

In 1914 the Albany Argus wrote that:

“Because of its exposed position in Steamboat square, tablet No. 1, ‘Fort Orange,’ was surrounded by an iron railing. The block and tablet are in good condition, but the railing is much bent and somewhat broken. This and No. 29, ‘Southeast Gate,’ in front of Van Benthuysen’s printing house on Broadway, will be in the centre of the roadway of the improved river front. No. 1 not only commemorates Fort Orange and the events connected with it, but also marks the site of its northeast bastion; while No. 29 locates the site of the residence of Peter Schuyler, Albany’s first mayor, as well as indicating the position of the southeast gate and the second city hall.”

There had been a much earlier fort, established following Hudson’s journey, called Fort Nassau. But it didn’t lead to or coincide with European settlement, so we don’t really consider it part of Albany’s history, just something that happened a bit before. Its location had been a bit of a mystery for many years, but John Wolcott thinks he has pinpointed it.

With thanks to Andy Arthur for pointing this out to us, we’re able to show the site that was excavated prior to the construction of I-787, across from the hotel that still stands on Broadway between what would be Liberty Street and Pruyn:

3 thoughts on “Albany Bicentennial Tablet No. 1: Fort Orange”