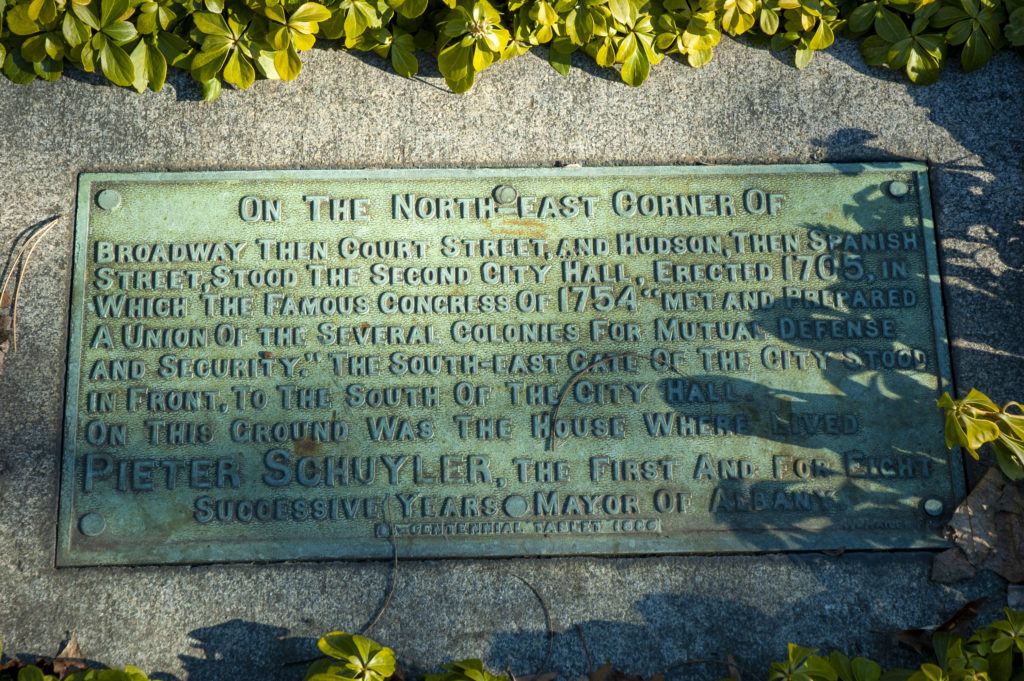

Today we have another Albany Bicentennial tablet that survived despite major construction at the area of its original placement more than a century ago. The Bicentennial Committee titled it “The South-East Gate,” but it covers much more than that:

Bronze tablet, 11×23 inches, in a granite block, similar to No. 7, in the walk, near the curb, in front of Van Benthuysen’s Printing and Publishing House on Broadway. Inscription:

“On the northeast corner of Broadway, then Court street, and Hudson, then Spanish street, stood the Second City Hall, Erected 1705, in which the Famous Congress of 1754 Met and Prepared a Union of the Several Colonies for Mutual Defense and Security. The Southeast Gate of the City stood in Front, to the south of the City Hall. To the north of this Spot a Bridge crossed the Rutten Kill, and on this Ground was the house where lived Peter Schuyler, the first and for sixteen successive years Mayor of this City.”

As can be seen, the actual tablet varied somewhat from the Bicentennial Committee’s approved copy, leaving out the bridge over the Rutten Kill and correcting the number of years that Pieter (as they chose to spell it) Schuyler was mayor.

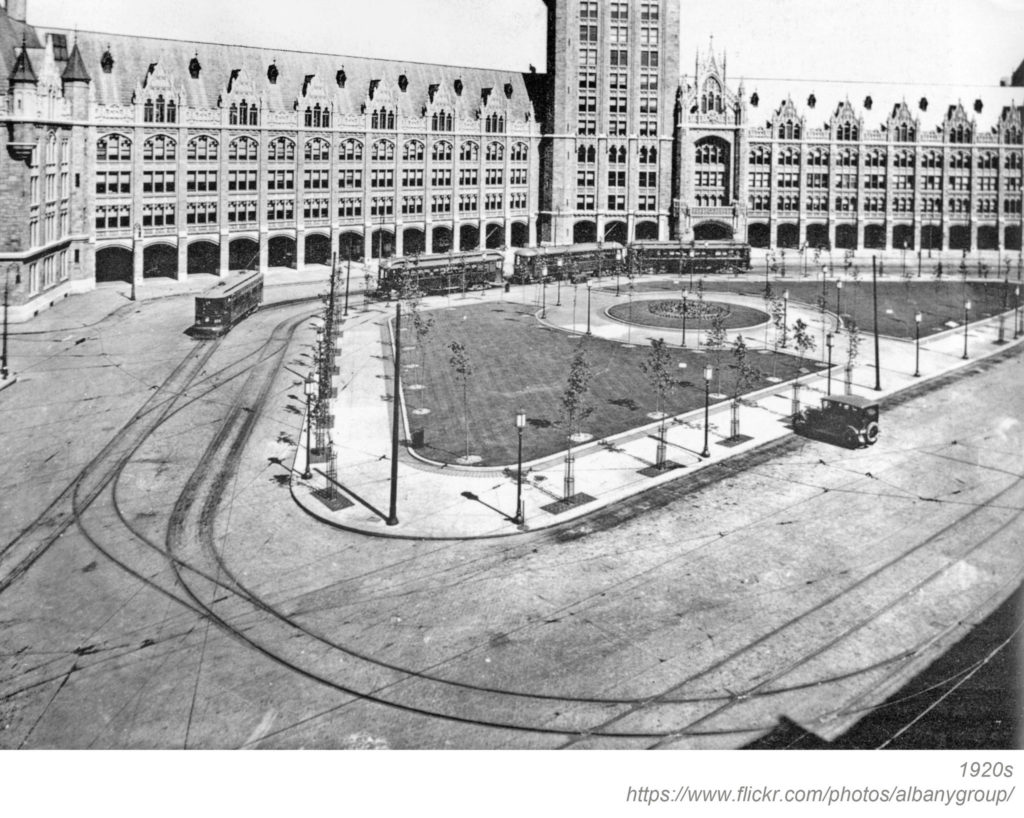

This tablet was still in place when the Argus reviewed their condition in 1914, but noted that like Tablet No. 1, this would be in the center of the roadway of an improved river front. Here, The Argus apparently got its markers confused, and provided some details that have nothing to do with this marker but do apply to the missing marker for the Schuyler Mansion.. We’re choosing to dismiss that as confusion – although it is accurate that the tablet had to be moved during construction of the Plaza, then perhaps the most important transportation hub in the city.

However it happened, this tablet did survive relocation and the reconstruction of the area, and is safely placed on a granite block today. The copy, as can be seen, somewhat changed from what the Bicentennial Committee approved, getting the years Schuyler served as mayor correct.

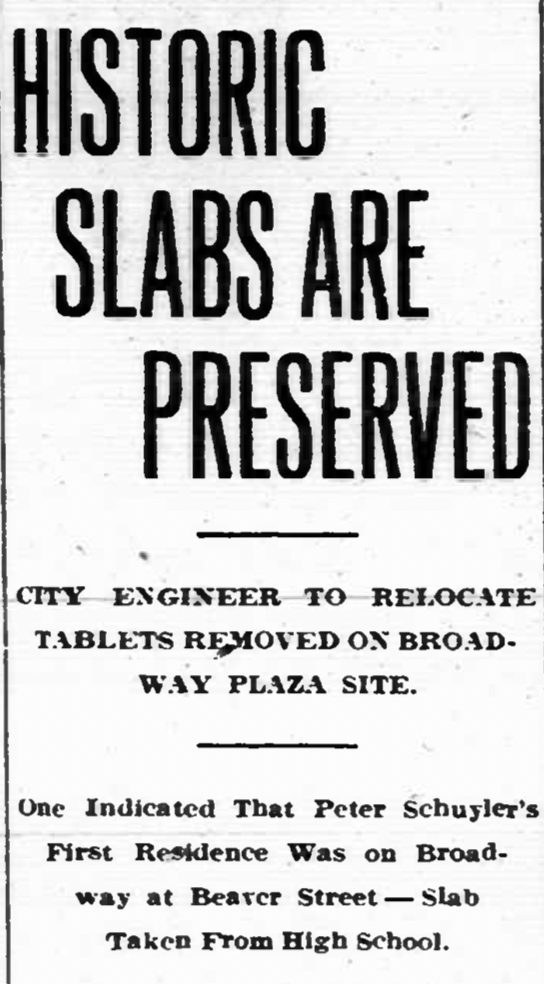

On October 3, 1915, The Argus declared “Historic Slabs Are Preserved,” indicating that the city engineer was to relocate tablets that had been removed from the Plaza site.

“Within a short time several of the bronze tablets that were removed by City Engineer Langan when the buildings on the site of the Broadway Plaza were razed will be replaced. Two of these are in Broadway, between Hudson avenue and State street; another is at the Steamboat square, but this will not be moved for it has simply been transferred to a point about 20 feet from the place where it was placed in 1886 by the bi-centennial officials.

The tablets were all removed to the house of the street department so as to be preserved while the work of razing the buildings on the Plaza site was in progress. Now that the work is showing considerable progress, it is the intention to re-locate the tablets in the places where they were intended to be. The city engineer had a map of the street made so as to get the tablets back in the exact location.

It has not yet been fully determined whether to put the tablets flush with the sidewalk or else to have them placed on a granite base. This matter will be cared for soon, however and the work done.”

The Steamboat Square tablet was Tablet No. 1. One of the other two was a tablet marking the first reading of the Declaration of Independence in Albany in 1776, shown below in its original form and with an interpretive plaque that tells you what it says. The third tablet was our current subject.

We won’t try to give a history of Pieter (or Peter) Schuyler here; there are plenty of other sites for that. And, as with the previous tablet, we don’t really know how long the gates of the city stood.

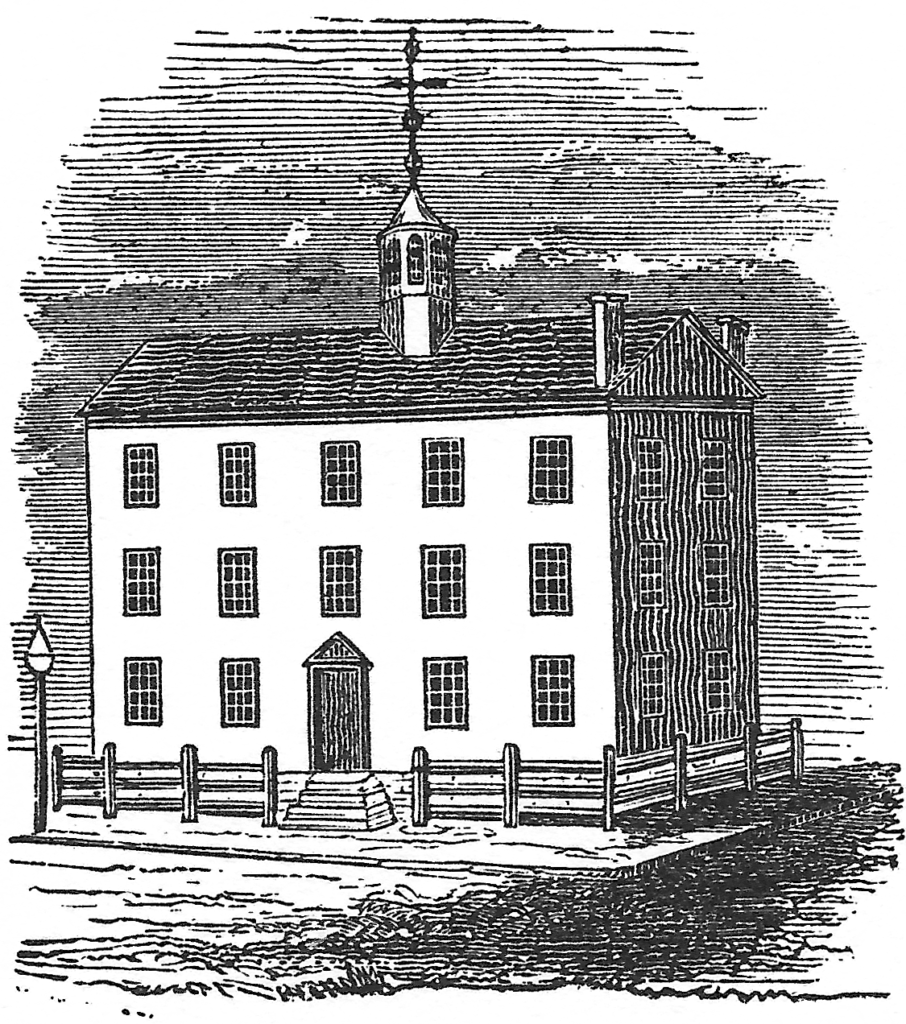

There seems to be exactly one drawing of the second city hall (and none of the first, for that matter), despite its important place in history – it was where Benjamin Franklin offered the Albany Plan of Union (little dreaming a street through Washington Park bearing that name would be most people’s only indication that ever happened). Nor do we have any images of Schuyler’s house.

Van Benthuysen Printing

We’ll take this opportunity to express our frustration in finding any good information on the history of Van Benthuysen’s printing operation, in front of which this marker was originally placed. Despite being a leading printer and publisher in Albany for decades, and possibly having brought the first steam press to the state, there is precious little information on Van Benthuysen’s history or operations. One of the few sources that has put anything together on Van Benthuysen is a page called DougSinclairArchives, which in writing about the architectural history of the Stafford House at 96 Madison Avenue, also touched on the Van Benthuysen family. Sinclair’s material seems well-supported by the other sources we could find, so we’ll rely on it here.

The Van Benthuysen family came to Albany around 1666. Obadiah Van Benthuysen, born in July 1787, began a five-year apprenticeship with printer Daniel Steele in October 1801, in which he was to learn “the Art, Trade and Mystery of Bookbinding.” He ended up taking over the business on Steele’s death. He first produced a publication called The Guardian at 19 Court Street, in 1807. In 1808, he moved the business to Liberty Street; five years later, he partnered with Robert Packard, and eventually Packard & Van Benthuysen located at the northwest corner of Beaver and Green Streets (later the site of The Capitol Hotel).

It is at that location that Obadiah Van Benthuysen is reported to have made the first successful use of a steam engine for running a printing press. “Albany and Its Business Houses” reported that in 1831 the Tract House of New York City tried a steam engine, but had been unsuccessful and returned to horse power, which was used to pull the belts that turned the drums and platen of a rotary press. In 1832 Van Benthuysen adopted a steam engine to the task and was successful. If reports are correct, he was already using steam to power his Albany Type Foundry; the date for the advancement is given as 1828.

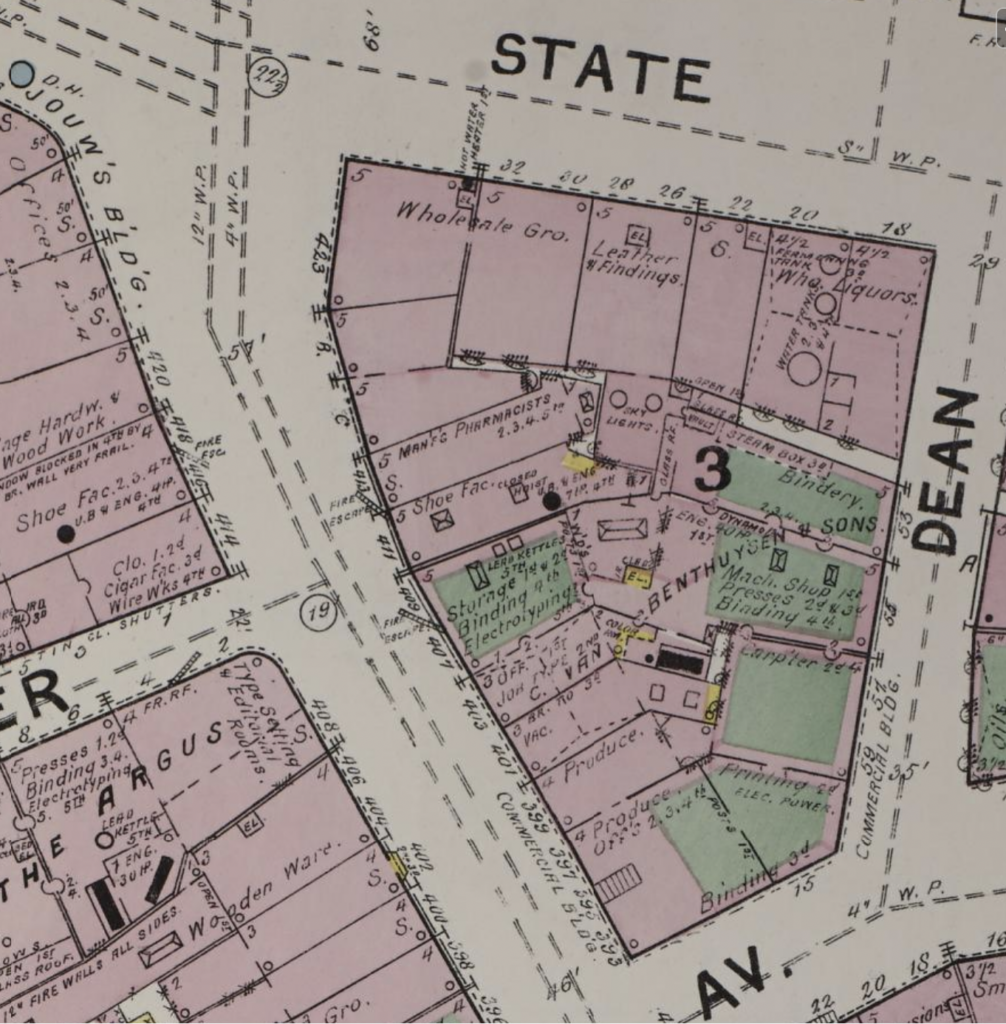

Van Benthuysen was also in the papermaking business, with operations in Cohoes, Castleton and Bath (later Rensselaer). Van Benthuysen then partnered with Edwin Croswell at the Albany Argus in 1823, printing not only the Argus but the official printing and binding for the State Legislature, a political plum of the day. Robert Packard left the business in 1838 (according to a Charley Mooney column in the Knick News). Obadiah died August 15, 1845. His sons Charles and Packard (presumably in honor of his old partner?) took over the business, and with their partner Cornelius Wendell in D.C., the company won a printing contract with both the United States Senate and the House of Representatives. At some point they moved their operation to Broadway, between State and Hudson, in what appears to be a series of old buildings adapted to their use. Van Benthuysen remained there until plans for the Plaza forced a move around 1913.

Packard moved on and Charles Van Benthuysen became the company’s principal. When his sons Charles Henry, Arthur and Franklin reached adulthood, the company reformed as Charles Van Benthuysen & Sons. The paper mills, later absorbed by other companies, went to Charles Henry, and Franklin ran the printing operation. The company ran until 1923, with its final location at 49 Sheridan Avenue being only 10 years old when it closed up shop. The Evening Journal at that time dated the business to the 1807 publication of The Guardian. “For years the establishment was located at 407 Broadway in a building that was razed to make room for the Plaza improvement.” Their Sheridan Avenue plant was taken over by J.B. Lyon printing, which then still had its building on Market Square, and which would merge with Williams Press late in 1923 to form a company with more than 1,000 employees that was then printing 70 different magazines as well as all sorts of other work.

There was actually a successor company to Charles Van Benthuysen & Sons – The V-B Printing Co., Inc., which moved to 2-4 Norton Street in 1923, and seems to have been more of a small job printer than the massive publishing operation Van Benthuysen was. Knickerbocker News columnist Charley Mooney said that paper salesman Frank T. Somma had gained the trust of the family owners, joined the company and wanted to continue it when Frank Van Benthuysen decided to close it – some of the business was continued, but he was only allowed to use the initials, not the old company name, and clearly he wasn’t sold the Sheridan Avenue plant, either. V-B was nominally headed by John W. Trueworthy, with Frank T. Somma as treasurer; Somma continued to run it through at least the 1960s. They moved to 1260 Broadway around 1969. (And if anyone wonders if that’s the same Frank T. Somma who once owned the White Sulphur Springs hotel on Saratoga Lake – yes it was. Charley Mooney mentioned it many, many times.)