We were doing so well up till now. The first five of the (arbitrarily numbered) plaques put up in celebration of the bicentennial of Albany’s charter in 1886 have all survived in some way. But here we hit our first missing plaque, with the one that marked the site of the first Lutheran church in Albany.

The land at the northwest corner of South Pearl Street and Howard Street in Albany has been occupied at least since the 1660s, and has hosted the original church, a 1786 replacement, a public market, a city administration building, the Mark Ritz Theatre, a parking lot, and now a parking garage. The one constant through the years: skeletons. Whenever digging is done there, skeletons are found. Specifically, Lutheran skeletons.

Here is the description of the tablet from the Albany Bicentennial Committee on Monumenting and Decorations:

Tablet No. 6—Lutheran Church.

Inserted on South Pearl street face of the City building. Bronze tablet, 16×22, inscribed:

“Site of the First Lutheran church. Built 1669. Removed 1816. Burial Ground around it. Between this Spot and Beaver Street, flowed Rutten Kill.”

The First Lutheran Church, Albany’s second church, dates its history to 1649, claiming to be the oldest congregation of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the United States. Its first building, which this marker once commemorated, was built in 1669 at the southwest corner of South Pearl and Howard, inside the Albany stockade. We have found no descriptions of that building, and it appears to have been gone (perhaps it burned, perhaps it was torn down, perhaps it just set out for greener pastures) when a new church building was constructed on the same site in 1786.

Joel Munsell, in his Annals of Albany Vol. 1, said he couldn’t ascertain the precise date of the first establishment of a Lutheran church (the congregation, not the building) in Albany. He noted that despite the struggles of the predominant Dutch Calvinist majority to establish their own church, they seemed to have energy to keep others from establishing competing houses of worship. Munsell said that the Lutherans (primarily the Scandinavians who had come in the early settlement) “seem to have been the first sect which the dominant party thought necessary to restrain in their mode of worship.” Complaints about their treatment led to their being permitted to worship in their own houses around 1656, but a Lutheran minister who arrived at Manhattan was forced to return to Amsterdam (the one in Holland). British rule brought formal approval of Lutheran worship in 1669, when Governor Lovelace proclaimed that “his Royal Highness doth approve of the toleration given to the Lutheran Church in these parts.”

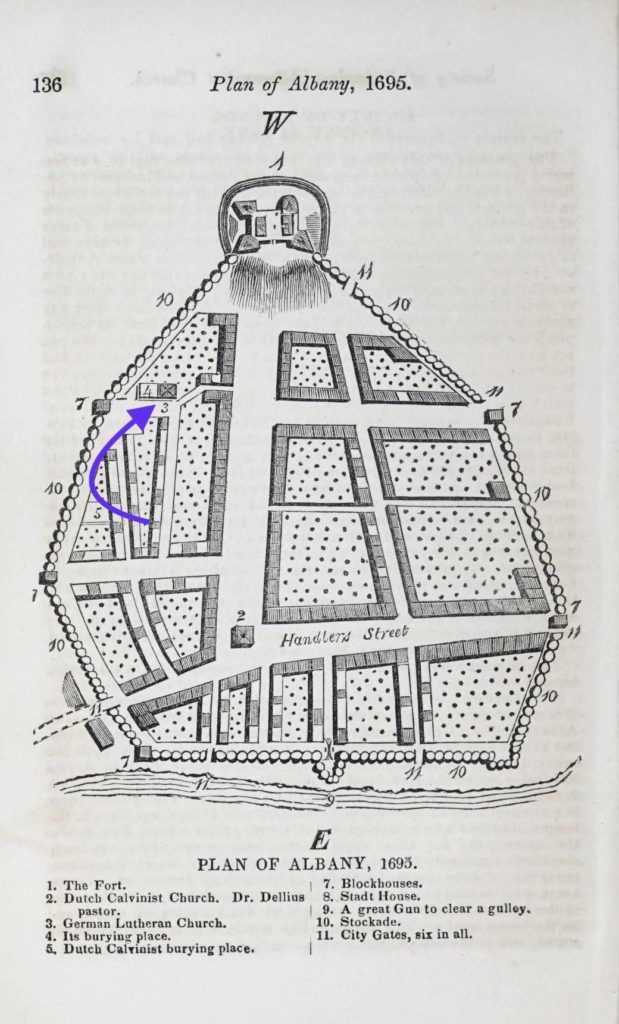

There seems to be agreement that the first Lutheran church building was constructed in 1669, the same year as official tolerance. It was built on a lot owned by Abram Staets (or Staats, or Staas). He conveyed the property to the church in 1680, but it was clear there was already a church on it at the time of conveyance. Staets conveyed the premises to elders and deacons of the Lutheran congregation Albert Bratt (or Bradt), Myndert Frederikse, Anthony Lispenard and Carsten Frederikse. Munsell refers to the 1695 map showing the “Lutheran church and burying ground, fronting on South Pearl street, and extending from Howard to Beaver street; or rather to the palisades, which formed the southern boundary of the city at that point.”

Munsell said he couldn’t learn much more about the history of that church from that point on. Although the Lutherans still had possession of their lot on Pearl street, “yet it is recollected by some of the elder citizens, that about the close of the revolution they had no church, but held their meetings for worship in a private house on the corner of Howard and Pearl streets, a front room in which was fitted up with seats sufficient to accommodate the few members belonging to the congregation at that time.” The church was “regularly incorporated” August 26, 1784, at time at which there was no church building; its pastor at the time, Heinrich Moeller, later wrote that he travelled with an elder of the church as far as New York and Philadelphia to raise money for a new building, which “was paid for soon after it was finished.” However, Moeller, who was only being paid half what he had been promised (plus firewood), soon moved to Pennsylvania for 12 years, after which he came back in 1801 for a second try.

“I found the charge easier than before, but my travels to Helderberg and Beaverdam, which congregations were necessary to make up a necessary living, proved injurious to my health, to which was added the heavy expense of keeping a horse and chaise, and the increase of prices for fire-wood and other necessaries. I left you the second time [in 1806], and am now comfortably settled for the short rest of my life.”

Rev. Heinrich Moeller

The new church building was completed and opened in 1786. By the way, services were in German until 1808, after which they were switched to English, “except one sermon in the forenoon of the last Sunday in each month.”

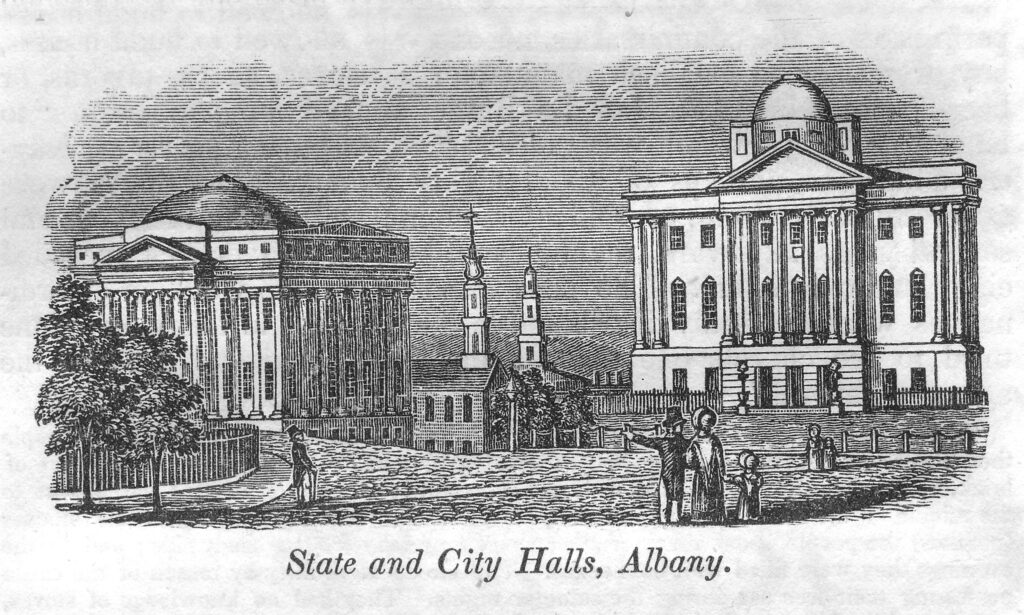

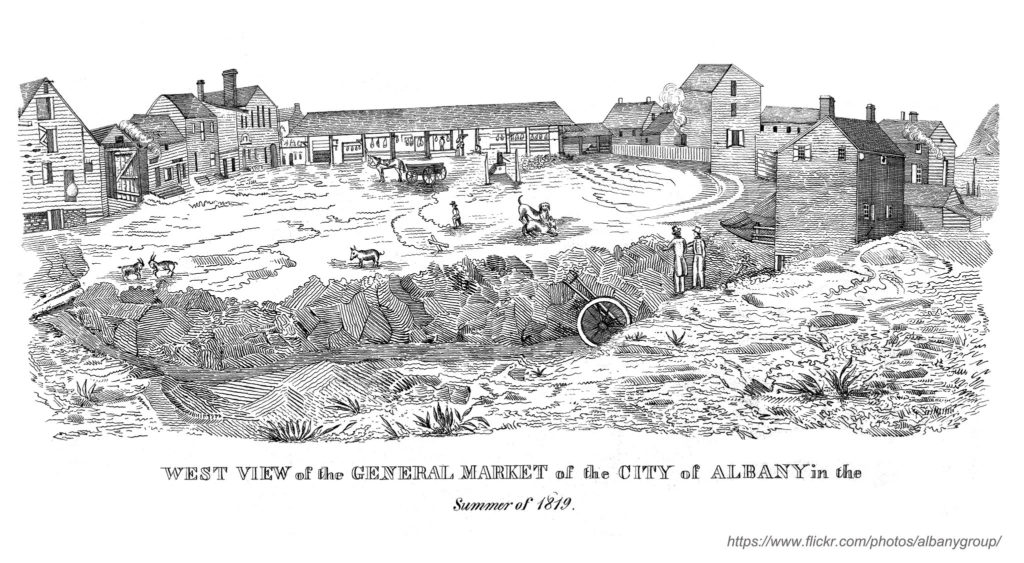

1816: Center Market

In 1816, the city purchased the church’s lot on South Pearl for a reported $32,000 in order to build a market on the site, or to expand the “Fly market” that already existed above the church on Howard Street. (It was then reported as bounded by South Pearl on the east, the Ruttenkill on the south, a “small run of water called Fort Killitie” on the west, and by Howard (“late Lutheran street”) on the north.) The common council gave the church a lot at Pine and Lodge streets, “on condition of the removal of their dead from the old burying ground on Pearl street. The expense of excavating the lot was $5,000.” The state then bought “the westerly and unoccupied part of their [Pine Street] lot, for $45,000, upon which the State Hall was erected. With this money the trustees excavated and built upon the property fronting on State, Park and Lancaster streets, which was occupied by them as a cemetery until the common council granted them their present cemetery lot by deed dated Nov. 1, 1803. These old cemetry [sic] grounds have been excavated to a great depth to make proper grades for streets and building lots – the cemetries [sic] of all the churches having been removed to their present location west of Knox street, on the south side of State, at about the same time.”

The cornerstone of the new church at Pine and Lodge was laid Sept. 16, 1816. Philip Hooker was the architect; the building was 40 by 60 feet, and cost about $25,000. It was repaired and renovated in 1848. Another building took its place; that building burned in 1934 and is now just a parking lot across from St. Mary’s Church.

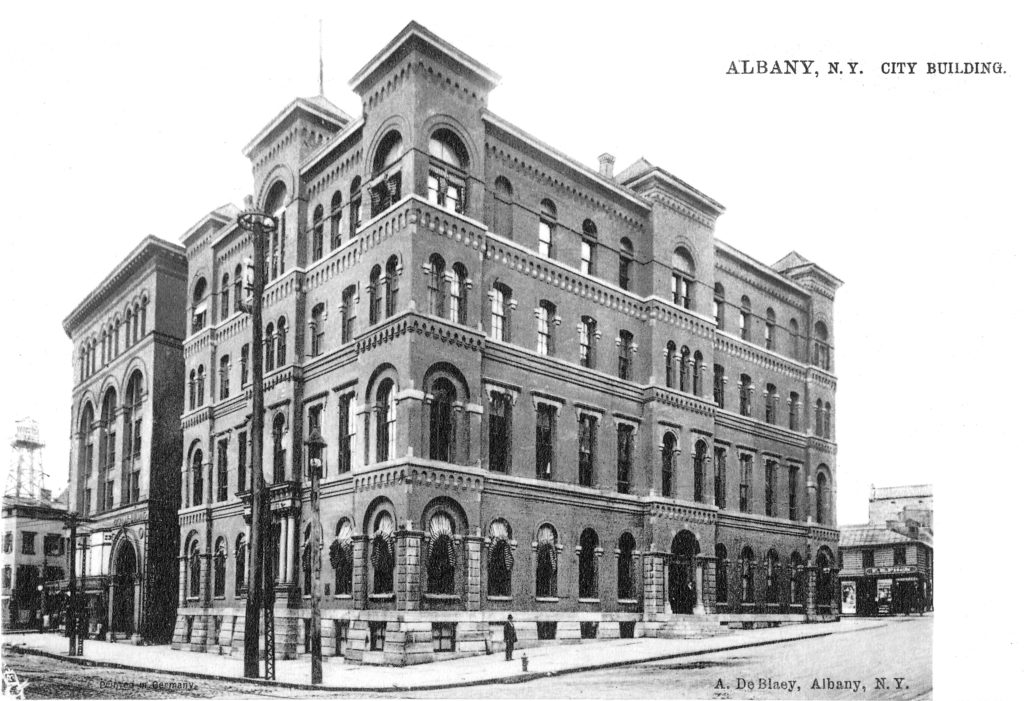

1868: The City Building and Bones

For many years, the site of the old church was occupied by a market building, often known as Center Market. Think of it like a commonly owned building where various producers could sell their wares, a sort of permanent farmer’s market. In 1868, a new city government building, eventually known by the illustrative moniker of “City Building,” was under construction. It was during excavation in August that workmen found that perhaps not all those bodies that had been buried at the old church had been moved. Initially, according to the Albany Morning Express, “they came upon three coffins lying close together. On being opened they were found to contain the bones of persons who were buried in them, in a tolerably good state of preservation. They were lying side by side, about five feet below the level of the sidewalk, and under that part of the market building occupied as Sawyer’s fish market . . . Soon after another coffin was discovered to the southward, and another to the westward.”

No headstones or other markers were found. The newspaper reported that “At first there were many speculations among the curious crowd as to how and when the ancient remains came there, for no one present had any idea of a burial ground having been in that vicinity.” Yeah, but then someone did what we all do — got out their copies of the Annals of Albany, from which the paper proceeded to recite the history of the site. (Seriously, Joel Munsell has to do everything around here.)

Other finds were made at the site, including a fireplace and hearth, “together with barrels of ashes, just as they were left.” We do not find what was done with the recovered remains, but given the year, we think re-interment at Albany Rural Cemetery would be likely.

With the construction of the City Building, the center market moved back a block to Howard and Williams; by 1884 it had moved to the area of Hudson, Beaver and Daniel streets.

The City Building became an active center of government, with police and local courts located there as well as departments of health, excise, charities, and the city clerk, among others. Police and fire chiefs were headquartered here. The top floor was a large hall that was used by the Jackson corps and police for drills. Fire at Martin’s Hall, home of the old Albany Theatre and immediately south of the City Building, spread to the top floor of the City Building, doing enough damage that reconstruction was necessary, and at that time the large hall was eliminated, replaced with more offices.

1923: The End of the City Building

By 1923, the City Building’s functions had been replaced by a new municipal building on Eagle Street, between Beaver, Howard and Daniel. and the City Building was to be torn down to make room for “a modern million dollar office building.”

The Knickerbocker Press lamented its loss, saying,

“For years, the steps leading to the main entrance of the building in South Pearl street have been a gathering place — a sort of forum – for persons widely known in the political and official life of Albany . . . The ‘forum’ is continued nightly even to this day. Of course, the faces have changed, but men active in official life still gather there.

“When the building is razed, persons who have been familiar ‘posts’ in front of the structure will have to seek new ‘headquarters’ for their nightly discussions.”

A developer named Herman Goodman was involved in constructing the new municipal building, replacing the old City Building, and he owned the DeGraaf building, which had replaced Martin’s Hall just south. Because this is Albany, the sale of the City Building got held up in political/legal intrigues centering on whether the alleyway between it and the DeGraaf building was a public street, and the sale was blocked at least three times by court order. Goodman appears to have gotten overextended, didn’t end up with the old building, and defaulted on his contract for the new one when it was nearly complete. The old City Building site went to a company called Goldfro Realty, which then sold it to the Lussier Hotel company of New York City, which announced in March 1924 that it intended to build a 400 room hotel on the site, without taking the alleyway that had been in contention. At the press announcement, Goodman complained loudly that he had lost money he felt entitled to. But in any case, the planned hotel never happened. Instead, we got the Ritz Theatre. And, most likely, we lost our bicentennial tablet around this time.

1926: The Mark Ritz Theatre

It’s not quite clear when, but the City Building, listed as 21 S. Pearl, was torn down some time after 1923 and replaced in 1926 by the Mark Ritz Theater, one of the Stanley Warner theaters (Albany’s Strand, Madison and Delaware were in the same chain). It was one of the first theaters in the nation to present talkies. It opened August 9, 1926 (showing Gilda Gray in “Aloma of the South Seas,” now a lost film about an erotic dancer).

It seems most likely that our missing bicentennial tablet went missing when the City Building was demolished around 1923. (It had been in place in 1914, according to the Argus.)

1964: Parking

In 1964, the Ritz building was sold to the Maiden Lane Parking Corp. It was noted that “The Ritz block is on the fringes of the South Mall, and within the area being considered for a civic auditorium for Albany.”

Now if you want to know where the first Lutheran church was sited, go down to the non-descript parking garage with retail that sits on South Pearl between Beaver and Howard. It would be nice if the plaque were somewhere on that garage.

1998: More Bones

We need to mention that in 1998, road construction at this intersection uncovered yet more graves. According to Albany Rural Cemetery, three graves were discovered on the site of the old Lutheran churchyard, along with such assorted items as wampum, bricks from the original Lutheran church, and pieces of pipes. The remains discovered were those of a woman and two men.

The woman was in her early 40s, one man was about 25 and the other was middle-aged. The younger man showed signs of tuberculosis. The pine coffin currently on display in the New York State Museum held the remains of the woman who has been nicknamed Pearl. A reconstruction of her face and skull are also part of the Beneath The City exhibit. There were no gravestones or coffin plates to identify the dead and they were believed to date to between 1710 and 1750.

The three sets of bones were placed in a single small coffin and, after a memorial service on May 15, 1999, were brought to the Church Grounds at the Albany Rural Cemetery and were laid to rest in the same section where later graves from the Lutheran lot at the State Street Burying Grounds (Washington Park) are also interred.

1 thoughts on “Albany Bicentennial Tablet No. 6 – First Lutheran Church”