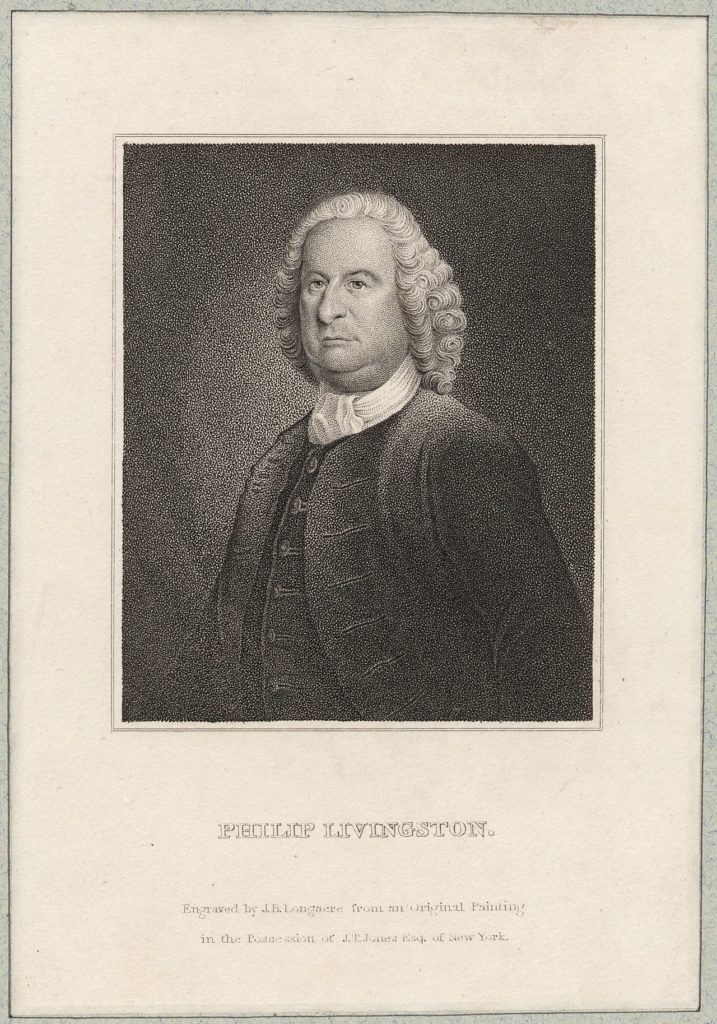

Continuing our series on the tablets placed around the city in commemoration of the bicentennial of Albany’s charter as a city, we have another one that has gone completely missing. Fortunately, it was replaced, in a way, but there seems to be no record of what happened to the original. This one marked the birthplace of Philip Livingston, most famous as one of New York’s signers of the Declaration of Independence, less famous as a privateer and slave-trader.

Tablet No. 12—Philip Livingston

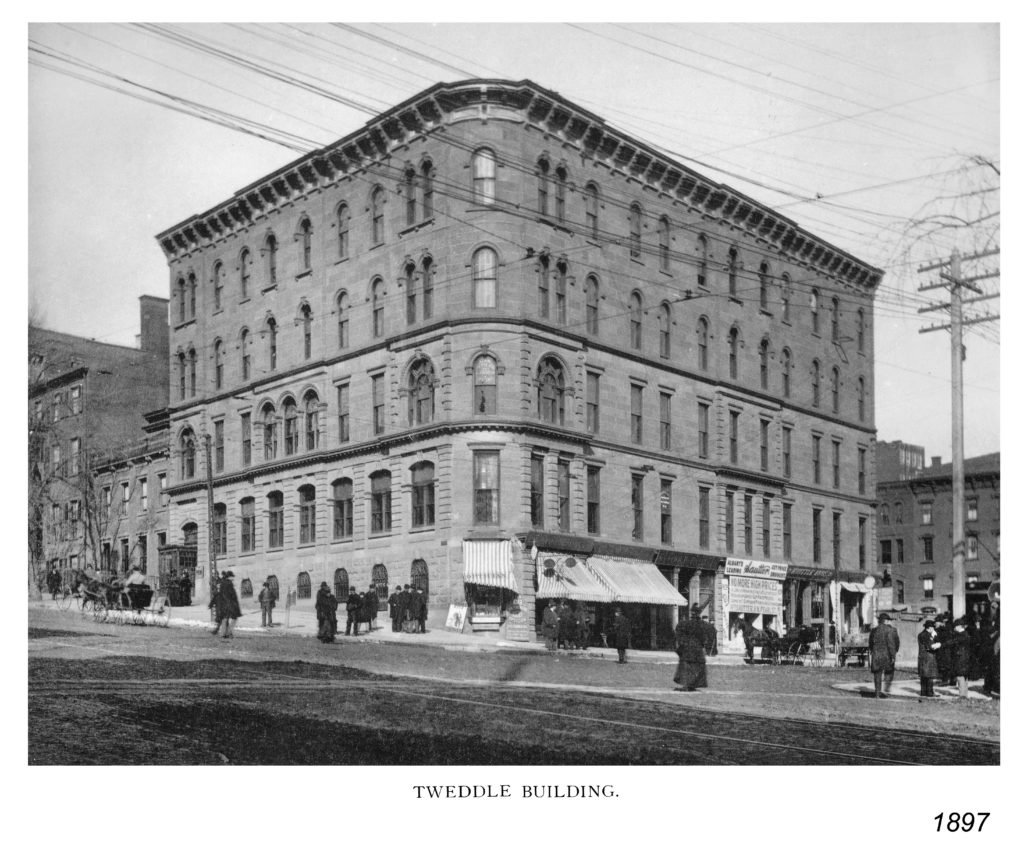

Bronze tablet, 16×22 inches, inserted in Tweddle building over Sautter’s apothecary store. Inscription :

“Upon this Site Philip Livingston, One of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, was Born 1716.”

Today, the fact that Philip Livingston signed the Declaration of Independence tends to be all we remember about him. Here in Albany, both Livingston Avenue and the Philip Livingston Magnet Academy (previously Philip Livingston Junior High School) are named for him. If you search the old newspapers for articles on Philip Livingston, you’ll find them with headlines like “Philip Livingston, Pathfinder of Liberty,” and the notation of “Philip the signer” helps us keep him separate from the other Philips, including his father. As with many of the founding fathers, his role is worthy of examination. Yes, he was an important figure in the movement for independence from Britain. At the same time, he was an inheritor of vast wealth who expanded his fortune through land speculation, privateering, and the slave trade.

So, how does one get to sign the Declaration of Independence? It helps to be born fabulously well-to-do, as Kurt Vonnegut would have said. The Livingstons were fabulously well-to-do. Robert Livingston, Philip’s grandfather, married Alida Schuyler Van Rensselaer, and was granted the lordship of Livingston Manor, which encompassed a significant portion of Columbia. Robert’s son Philip, who became the second lord of the manor, was born in Albany in 1686 in the family house at what would later become known as the Elm Tree Corner, the intersection of State and Pearl. This Philip married Catherine van Brugh in 1708, and became a powerful merchant, dealing in furs, grain and flour. It appears he was also very actively involved in the slave trade as well – not just owning slaves, although he certainly did that, but owning slave ships and actively trading for enslaved humans.

According to Cynthia Kierner (“Traders and Gentlefolk: The Livingstons of New York, 1675-1790”), Robert’s son “Philip’s extensive trade with the West Indies led to his involvement in the African slave trade. In the 1730s and 1740s, he was one of New York’s leading importers of slave labor from the sugar islands, and also one of few New Yorkers who imported slaves directly from Africa before the abolition of the Spanish Asiento in 1748. In 1738, Philip [the signer’s father] bought a one-third share in a voyage to Guinea, where two hundred slaves were purchased and consigned to his son Peter Van Brugh Livingston and his partner in Jamaica. New York’s direct trade with Africa grew significantly after 1748, and the Livingstons continued to be among the colony’s leading Africa traders.” Kierner names the eldest sons, Robert and Peter, as the most extensively involved in Philip the elder’s business, and it was Robert who inherited the manor in 1748. But other sources also connect Philip the signer (as he is commonly called) with the family slave trade.

Philip the signer, subject of this bicentennial tablet, was born in the family’s Albany house in 1716. Legend has it that it was he who made it the Elm Tree Corner, by planting a tree in front of the family home in 1735, but many have cast doubts on that, nearly as far back as the story goes. (We’ll talk much more about the Elm Tree Corner with Bicentennial Tablet No. 16).

Businessman, Politician, Privateer, Slave-trader

Our Philip probably didn’t live in Albany very long; the family’s manor house was Clermont (in Tivoli), and he was only 12 when his father became lord of the manor. He graduated from Yale College in 1737, came back to Albany for a bit where he married Christina Ten Broeck. The Livingstons, who had nine children, made their home on Duke Street in New York City (probably the current Stone Street), and maintained an estate at Brooklyn Heights that overlooked New York harbor. During the French and Indian War, Philip was active in privateering, owning shares in six privateering vessels. (For the unfamiliar, privateering is piracy with a sheen of legitimacy because it is undertaken against an ostensible enemy.) New York’s Signers of the Declaration of Independence says, “Philip Livingston apparently was not above winking at the law for profit, since he was also part owner of the ship Tartar which was involved in illicit wartime trade with Spanish and French ports in the West Indies.” It also appears that Philip was actively involved in the slave trade, although there is sometimes some confusion about which Philip was which. He was part of his father’s company, Philip Livingston & Sons, along with brother Peter, and that company was very active in bringing enslaved people to New York.

His activities in New York city were extensive. “The Livingstons of Livingston Manor” by Edwin Brockholst Livingston reports that Governor Charles Hardy wrote of Philip in 1755 that “among the considerable merchants in this city no one is more esteemed for energy, promptness, and public spirit, than Philip Livingston.” He was an alderman for the East Ward of the city from 1754-1762. He was a founder of the New York Society Library, the first president of the St. Andrew’s Society in 1756, a founder of the New York Chamber of Commerce in 1770, and one of the first governors of the New York Hospital in 1771. He was also one of the early advocates for the establishment of King’s College, now known as Columbia University.

As a figure in government, after his time as alderman, Philip was later elected to the general assembly in 1759, and rose to the position of speaker. He was selected as a member of the Stamp Act Congress in 1765, speaker of the New York General Assembly in 1768, the first Continental Congress in 1774, and to the Congress which declared independence in 1776. He was also involved in a 1774 association to “execute the plan of commercial interdiction against Great Britain,” was president of the New York provincial congress and charged with framing a new constitution for the colony. He was elected a Senator under the new constitution and took his seat in the first Senate in September 1777.

When the British captured New York City in 1776, the Livingstons moved up to Kingston. Their Duke Street home became a barracks, their Brooklyn Heights home a hospital. When the British took Kingston in 1777, they ventured across the river and took pains to burn the estate at Clermont. The Livingstons had moved to the relative safety of Albany, along with the rest of New York’s government.

Livingston’s health was poor, as he suffered from dropsy (now edema), but he maintained his commitments to the revolutionary government. It was as New York’s delegate to Congress that he found himself in York, PA, where he died suddenly while attending the sixth session of the Congress; he was buried in York’s Prospect Hill Cemetery.

While those activities are well-documented and repeated in various biographies, Philip’s involvement in the slave trade is not. Edwin Brockholst Livingston’s book, while giving a very rich history of his own ancestors, barely mentions the slave trade, other than to say that, “Though accustomed to the ownership of household slaves themselves,” the Livingston family did not align themselves with those who objected to Jefferson’s clause in the original draft of the Declaration of Independence “rightly condemning the iniquitous slave trade.” But without supporting documentation, this may be wishful thinking or willful ignorance of a family shame, writing as he was in 1910. It is true that Philip’s brother, New Jersey Governor William Livingston, wrote in favor of abolition and applied to the New York Manumission Society, to which his cousin Chancellor Robert R. Livingston also belonged.

Despite being fabulously well-to-do, Philip died in such debt that his executors renounced the administration of his estate, and it took an act of the State Legislature to name trustees to resolve the debt. Have no fear for the poor family – Livingston Manor continued on as a feudal estate in a new form. Livingston’s grandson was Stephen Van Rensselaer III, the so-called “good Patroon,” so the family had control of both the massive feudal manors in New York. Columbia University estimated that in the 1790 census, the various branches of the Livingston family owned 170 slaves. It’s most interesting that they quote Robert R. Livingston, who continued to own slaves, as arguing against a bill that would have barred Black people from voting and holding office. “Rendering power permanent and hereditary in the hands of persons who deduce their origins from white ancestors only” would lay the foundation for a “malignant . . . aristocracy.”

What happened to the bicentennial tablet?

The Bicentennial Committee report says the tablet was inserted over Sautter’s apothecary, a drugstore in the Tweddle Building, but we can’t see it there in this detailed picture of the Tweddle Building, courtesy of the Albany Group Archive. It’s possible it’s the dark spot in the wall just above and to the left of the optician’s awning – which would put it in an ironically difficult position to read. It’s also possible it’s behind one of the Sautter’s signs.

But the Argus in 1914 reported there was already some mystery around the tablet even then: “There is no indication of any of the tablets at the place mentioned and Charles B. Krum, of the firm of William Sautter & Co., who was with the firm in 1886, does not remember any tablet having been placed there. On the other hand, Major Harmon Pumpelly Read, the sole surviving member of the monumental [sic] committee, is of the opinion that the tablet is still attached to the building and is behind Sautter’s large sign.”

So perhaps the plaque was gone before the Tweddle Building was finally razed in 1915. There is a replacement, but we can’t help but wish the original had survived.

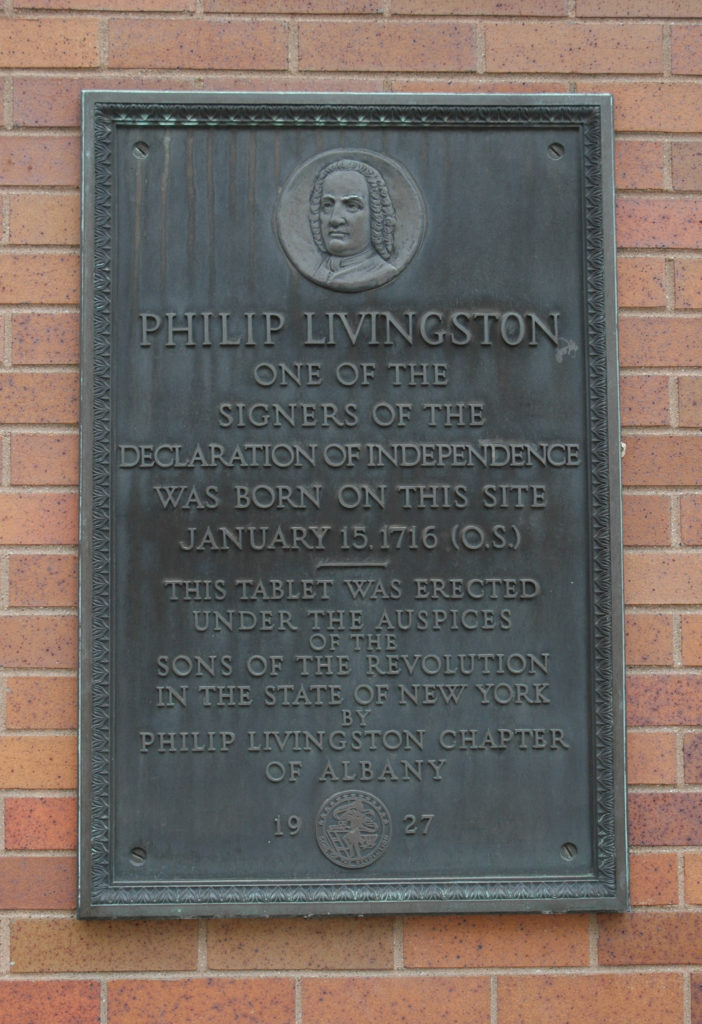

The replacement tablet

The marker that currently adorns the side of the colossally nondescript building holding down the Elm Tree Corner was cast and placed on the Ten Eyck Hotel in 1927 by the Philip Livingston chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution (who also cast the marker for Col. Marinus Willett in Washington Park). It has nearly the same copy as the bicentennial marker, adding the specific birth date and devoting as much of the plaque to the beneficence of the Sons of the Revolution as to the plaque’s subject. The ceremonies for the plaque involved a flag ceremony and color guard, bagpipes and speechifying. It’s interesting that there were quite a few newspaper articles on the planning and installation of the marker, and yet not one of them references that fact there had been a previous marker for that very purpose. We’re more than a little bit happy and more than a little bit shocked that this more recent marker survived the demolition of the Ten Eyck and its replacement by the ’70s structure that originally housed the modern Albany Savings Bank, and now houses a Citizens Bank and Starbucks.

Hi Carl … great article! I do very “junior” genealogy research on my family name (Livingston’s from Jamaica) and was wondering if you are aware of any contacts for this family above w/ rooted genealogies from Jamaica.

My 4th Great-Grandfather is Henry William Livingston born late 1700’s. The link currently has his father as being Phillip Phillip Livingston (1741-1787) as he had a son Henry around the same time in Jamaica. I do not think the link is accurate but wanted to see if I could prove/disprove.

Is there a contact that you are aware of that I could connect with? My information is below.