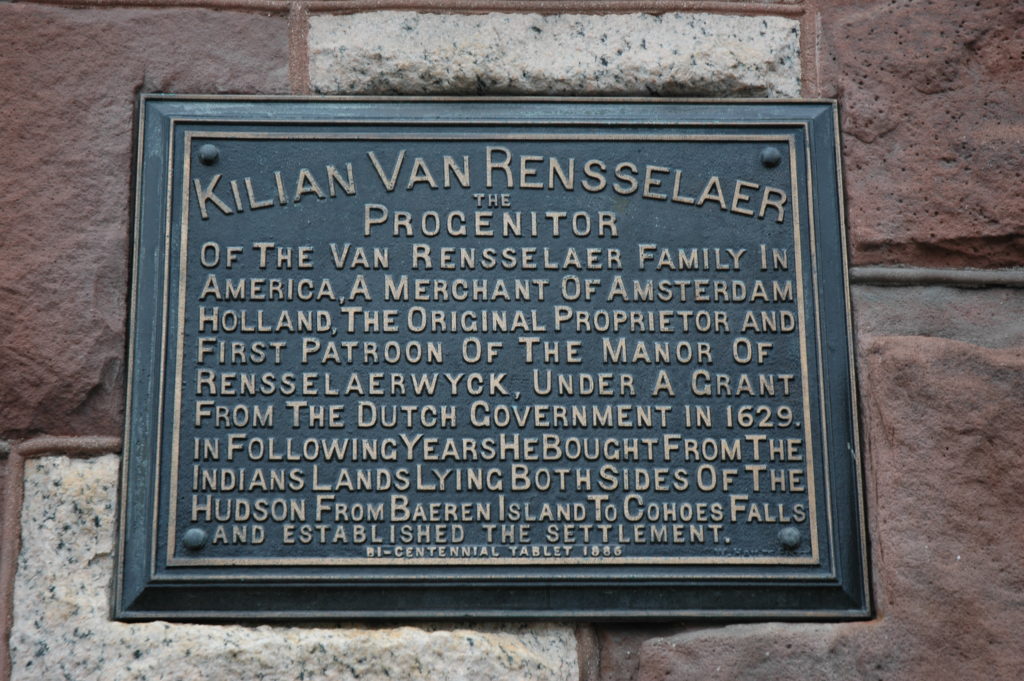

Continuing our series on the bronze markers that were placed by the Albany Bicentennial Committee in 1886 – the words below were approved to commemorate the first Patroon:

Tablet No. 4—The “First Patroon”

A bronze tablet, 16×22 inches placed in the City Hall, and thereon inscribed:

“Killian Van Rensselaer, the Progenitor of the Van Rensselaer family in America, was a Merchant of Amsterdam, Holland, and the Original Proprietor and first Patroon of the Manor and Rensselaerwycke; Patent Granted

him by the Dutch Gov’t in 1629.

The following year he bought from the Indians Lands lying on both sides of the Hudson River from Baeren Island to Cohoes Falls and Established the Settlement.”

This tablet (somewhat edited from the copy above) still exists on the front wall of Albany’s City Hall, which was pretty much brand new in the year of Albany’s bicentennial, 1886:

A note: the vast majority of historical documents spell the Patroon’s name as “Kiliaen,” so that’s the spelling we’ll go with here.

What’s a Patroon?

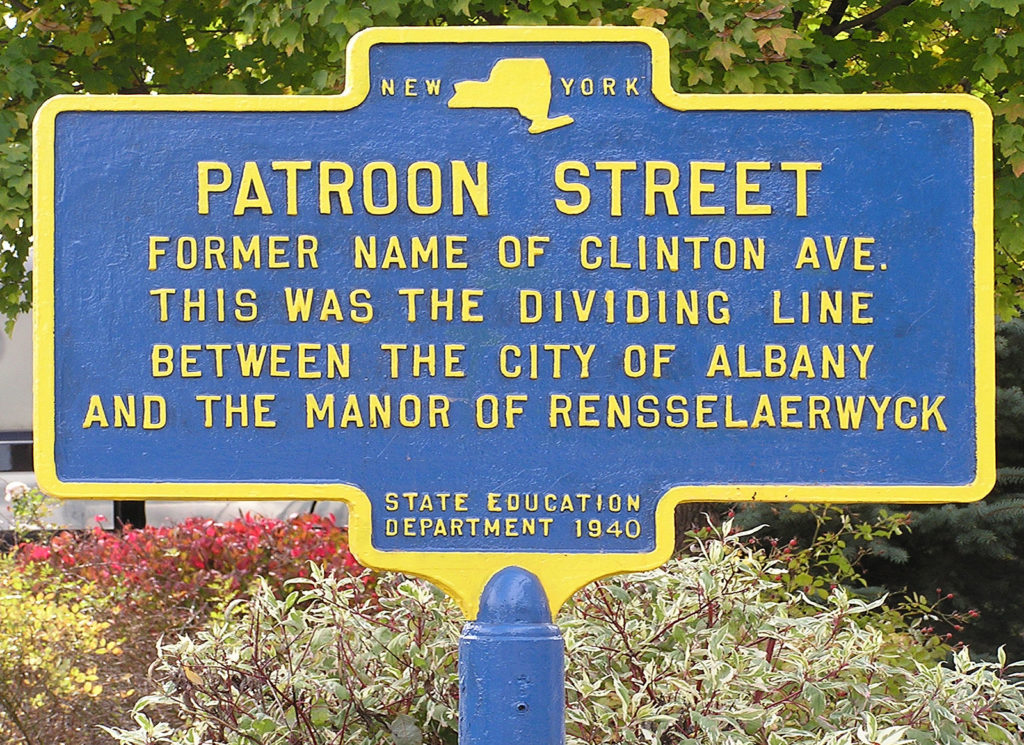

Generally, a Patroon is not someone we’d probably like to celebrate today, but there is no question that the first one, Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, was responsible for white settlement in the area. Members of the Dutch West India Company could select lands and erect them into a patroonship “under his exclusive personal proprietorship and governmental authority.” This system was what brought white colonists to lands claimed by the Netherlands. Kiliaen Van Rensselaer’s agent, Bastiaen Jansz Krol, negotiated terms of sale of land with Mohican representatives in 1630, a time when Europeans had already complicated previous conflicts between Mohicans and Mohawks, and the Mohicans were migrating eastward across the Hudson River into Massachusetts.

Initially settlement in what was soon called Rensselaerswijck (or some variation thereon) was mostly on the east side of the river in Greenbush (from the Dutch “Grönen Bosch,” which means … “green bush”). As W.W. Spooner* put it, “It was Van Rensselaer’s wise and far-seeing policy to settle his colonists in close proximity to one another, instead of distributing them widely. By this plan of concentration of settlement he secured for them the advantages of intercourse, of union for defensive purposes, and of progress to the dignity of a community within a reasonable time. The point chosen was the vicinage of Fort Orange, now Albany. The fort was the first trading post erected by the Dutch on the Hudson after the discovery, and up to Van Rensselaer’s time had existed merely as a station incidental to the fur trade, no attempt whatever being made to colonize the country.”

It does not appear that Kiliaen Van Rensselaer ever actually set foot on these shores, but he set up a feudal system of tenancy that persisted for more than two centuries. It outlasted even slavery in New York, and it should be noted that Van Rensselaer’s descendants were significant slaveholders as well.

Kiliaen Van Rensselaer died young, about 51 years old, in 1646. Kiliaen’s eldest son, Johannes Van Rensselaer, became the second patroon; like his father, he never came to Rensselaerswijck. The colony at this time was run by vice governor Brandt Arendt Van Slichtenhorst (succeeding Arendt Van Corlaer’s somewhat brief term). Kiliaen’s second son, Jan Baptist, came to Rensselaerwijck in 1651 and assumed directorship in 1652, without being named patroon. He returned to Holland, and Kiliaen’s third son, Jeremias Van Rensselaer, became the third patroon, coming to the colony in 1658. It was during his patroonship that New Netherland was surrendered to England, in 1664, but Jeremias held British citizenship and thus qualified to own land and continue to exercise his rights. He worked for many years to establish the patent for his brothers and sisters as well as himself, and a grant for Rensselaer Manor was finally made in 1685, 11 years after Jeremias’s death. Brother Nicolaus took control then, in 1674, but he died in 1678. Ryckert, Kiliaen’s fifth son, became the fifth patroon. It was Ryckert who owned the farm called “The Flatts,” which he sold in 1670 to Philip Pieterse Schuyler, and is now known as Schuyler Flatts. (This according to Spooner; other sources lay out somewhat different succession.)

The patroonship was technically an English manor or lordship, as of 1685, but the title of “patroon” persisted. The first lord of the manor was Kiliaen, son of Johannes (the second patroon). This Kiliaen died in 1687 without children, and succession devolved on Jeremias’s eldest, another Kiliaen, the second lord of the manor, who died in 1719. His son Jeremias became the third lord of the manor; his father died when he was only 14, and Jeremias died unmarried in 1745, moving the lordship to Stephen Van Rensselaer I, the fourth lord, who died shortly thereafter in 1747. His sixth child, but the eldest surviving son, Stephen II, became the fifth lord of the manor when he was but five years old; his brother-in-law Abraham Ten Broeck ran his affairs until he reached the age of majority. It was Stephen II who built the manor house in 1765. Like most Van Rensselaers, he died fairly young, at 37, in 1769, and that led to his son, Stephen III, becoming the sixth and last lord of Rensselaer Manor.

The “Good” Patroon

Stephen Van Rensselaer III, often simply abbreviated “SVR,” was called “The Good Patroon.” A graduate of Harvard, he was something of a progressive who wanted to see development of what had been a very stagnant manor, dramatically lowering rents on his thousands of farms to stimulate growth. He was an active politician, and advocated for a canal to reach the Great Lakes. He fought as a general in the War of 1812, and founded the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

He also, despite being the “good” patroon, vigorously defended and extended his feudal control over his vast holdings, which was outlawed in New York in 1787. Have no fear for poor Stephen: everybody’s hero Alexander Hamilton helped him in extending this system by creating the “durable lease,” under which tenants were allowed to work sections of land for a payment of 10-20 bushels of winter wheat per 100 acres, four fat fowl, and a day’s labor with a team of horses and wagon (the latter could be converted to firewood, by informal agreement). The patroon maintained all timber, mineral and water rights. If a tenant chose to sell, a quarter of his selling price went to the patroon – and all the tenant could sell was the right to work the land, and any improvements he had made to it. The patroon still owned everything. How the durable lease was different from the Patroon system is really hard to discern.

Although SVR reduced and often just ignored rents, he would not divide up his estate, and at a time when westward expansion was calling, his decision was harmful not only to his own position but to the development of his lands and the very development of Albany and Rensselaer counties. Even though his rents were paid largely in produce, wheat and chickens, because he never forced payments, indebtedness accumulated to the point that when he died in 1839, he was owed $400,000 by his renters. (It’s not easy to discount currency that far back, but let’s say that’s about $12 million in modern money.)

Economically, the whole patroon/manor system disincentivized investment in local land and structures, and incentivized anyone who didn’t want to live under the thumb of a manor-lord to move west. But it did keep absolute control and wealth concentrated in a very few families. In 1846, the SVR estate had 1397 leasehold farms in Albany county, covering 233,900 acres; in Rensselaer county, they held 1666 leasehold farms, totaling 202,100 acres. Between them they were charged with providing 43,600 bushels of wheat a year in rent. You had to pay the patroon, and if you made any improvements (say, a house), when you sold them off you had to pay a quarter of that to the Patroon.

This exploitative system began to break down after the death of Stephen Van Rensselaer III in 1839; his heirs aggressively pursued back rent (as they were directed to by his will, and required to do in order to pay the estate’s significant debts). Even current rent was hard for many to pay because, for starters, this wasn’t great soil. Efforts to collect led to the Anti-Rent War, which saw militant tenants organizing, riding, and creating some terror dressed as “Calico Indians.” (John L. Brooke, in “Columbia Rising,” says that “in assuming Indian identities, the Anti-Rent militants signaled their sense of being excluded from routine civil life.” He wrote that in 2010; now we can assign even more meaning to that as we think about their willingness to continue to exclude Native Americans from civil life.) It coincided with the division of the manor between SVR’s two eldest sons, east and west of the river. The Anti-Rent movement succeeded in getting constitutional amendments in 1846 abolishing the lease-hold tenures and the quarter-sales requirements (anyone selling his lease to another was required to pay the manor one-quarter of the proceeds), and that essentially ended the manorial system.

*(We owe the Van Rensselaer family lineage to an article by W.W. Spooner, “The Van Rensselaer Family,” in American Historical Magazine Vol. 2., No. 1, January 1907. Other sources may number patroons differently.)

The Patroons and Slavery

It’s no accident that the histories of the various patroons and the institutions they created barely mention slavery. When they do, they position it, as is commonly done for northern states, particularly New York, as a comparatively minor happenstance. While this makes white people who live in the area feel better about its place in history, it is simply not true.

It is not minor, for instance, to own 15 other human beings, as Stephen Van Rensselaer III, the “good” patroon, did in 1790. (In 2007, Fortune magazine ranked SVR as the tenth richest American of all time.) That he did some very good things does not negate that he did some very bad things, like owning human beings, or working out a way to continue his feudal powers despite their having been outlawed. Of course, many of his tenants owned slaves as well. (In 1790, Albany County had 3722 enslaved persons counted, the most of any county in the state, and the vast majority of those had to have been on Van Rensselaer property.)

What enslaved persons previous patroons may have owned is not as easy to discern, and scholars are really just starting to dig into the topic that has been so well hidden for so long. But we know that there were slaves in Albany since before it was chartered, and Albany’s richest families were all involved. The Discover Albany site notes: “Jan Baptist van Rensselaer sent his younger brother Jeremias from Albany to Manhattan to select a slave for their farm and homestead in 1657. His brother wrote back and said he had purchased for 50 beaver pelts ‘a tall, quick fellow who can work well.’ His name was Andries.”

Leave a Reply