Two notes: One: throughout this article there are variable spellings of Burdett-Coutts, and when quoting, I’ve reflected the spelling used in the source I’m quoting at the time. Two: of course the source materials use racial terms that are no longer acceptable, but as they were not intended as directly offensive, I have copied those uses when quoting source materials.

This is the story of a marker, or plaque, if you prefer. A marker that was intended to honor the Black citizens of Albany at the time of the city’s bicentennial, and specifically to mark the location of an elm tree contributed by one of Albany’s leading citizens, Dr. Thomas Elkins. We know the tree was planted, we know the marker was made (some years later) – but we can’t determine if it was ever placed in Washington Park. If it was, does it survive somewhere? If it wasn’t, why wasn’t it?

Albany’s Bicentennial: Many Guns Saluting

In 1886, Albany held a huge celebration of its bicentennial. it began on Sunday, July 18, with a day of religious observance. Monday was Educational Day, a day for the school children to take part in exercises. Tuesday, July 20 was All Nations Day — “the day to be set apart for national sports, exercises and observances; the same to be under the direction and control of the German, Irish, English, Scotch, French, Italian, Holland other national societies, in such manner and form as they may determine and in such places as they may select.” The day was also to feature a regatta, followed by a nighttime illuminated boat parade. July 21 was Civic Day, for which sleeping in was not advised, as it was begun with a 38-gun salute at sunrise. The national societies, Knights Templars, Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, singing societies, and fire companies would parade that day, followed by more regatta and “a grand historical pageant, under calcium and electric light and colored fires.”

Oh, if you hadn’t been startled from your bed by the 38-gun salute on that Wednesday morning, perhaps the start of the actual Bi-Centennial Day on Thursday, July 22 would do the trick: two hundred guns were fired at sunrise, fifty each at four different places. Then a military procession and the full bi-centennial exercises and night-time fireworks. That didn’t end it though, for on Friday, it was Trades and Manufactures day, with all the trade unions, assemblies, manufacturing and business interests, grocers, butchers, and brewers, printers, tanners and cigarmakers, followed by an afternoon concert and night time singing by the singing societies in Capitol Park “with a discharge of rockets, bombs, etc., as a grand finale.”

All this is by way of background for telling a story and hoping to find the ultimate disposition of a historic marker placed in Washington Park by the Burdett-Coutts Benevolent Association (read a little bit more about them here) on behalf of the Black residents of Albany. Their formal participation appears to have been limited to All Nations Day, a celebration of immigrant cultures, which both makes sense and doesn’t. If any of the Black societies participated in other days’ programs or parades, it wasn’t recorded.

Dr. Thomas Elkins, one of Albany’s most fascinating African Americans of the 19th century, proposed to donate an elm tree to be planted on behalf of the community, “as a memorial of the colored citizens.” At a meeting of a large number of Black residents at the African Methodist Episcopal Church on June 16, 1886, led by J.F. Chapman, Robert McIntyre, representing the Burdett-Coutts Association, was authorized to secure permission to plant the tree in Washington Park. Burdett-Coutts would also parade, “and had invited the Nemo club, of New York city, as their guests.”

The All Nations Day Ceremonies

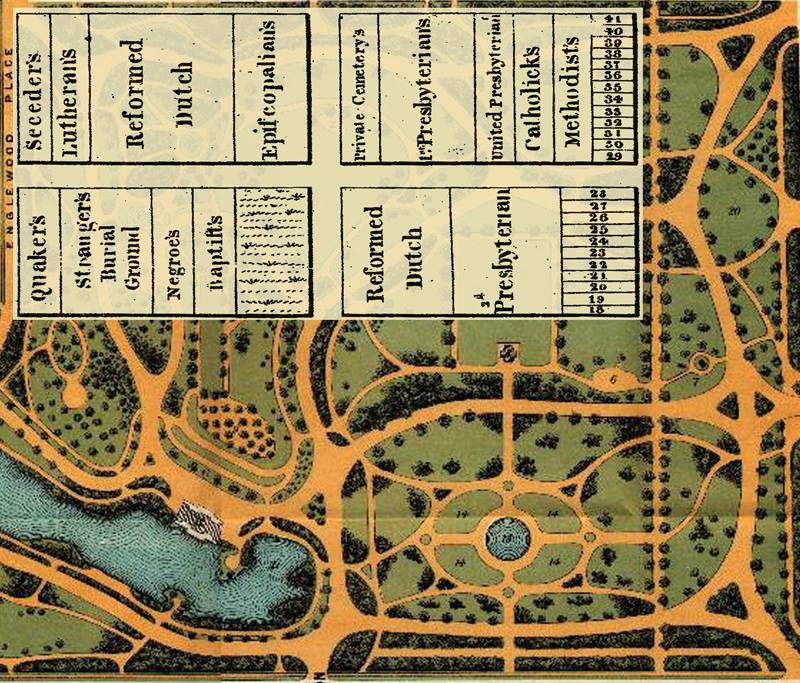

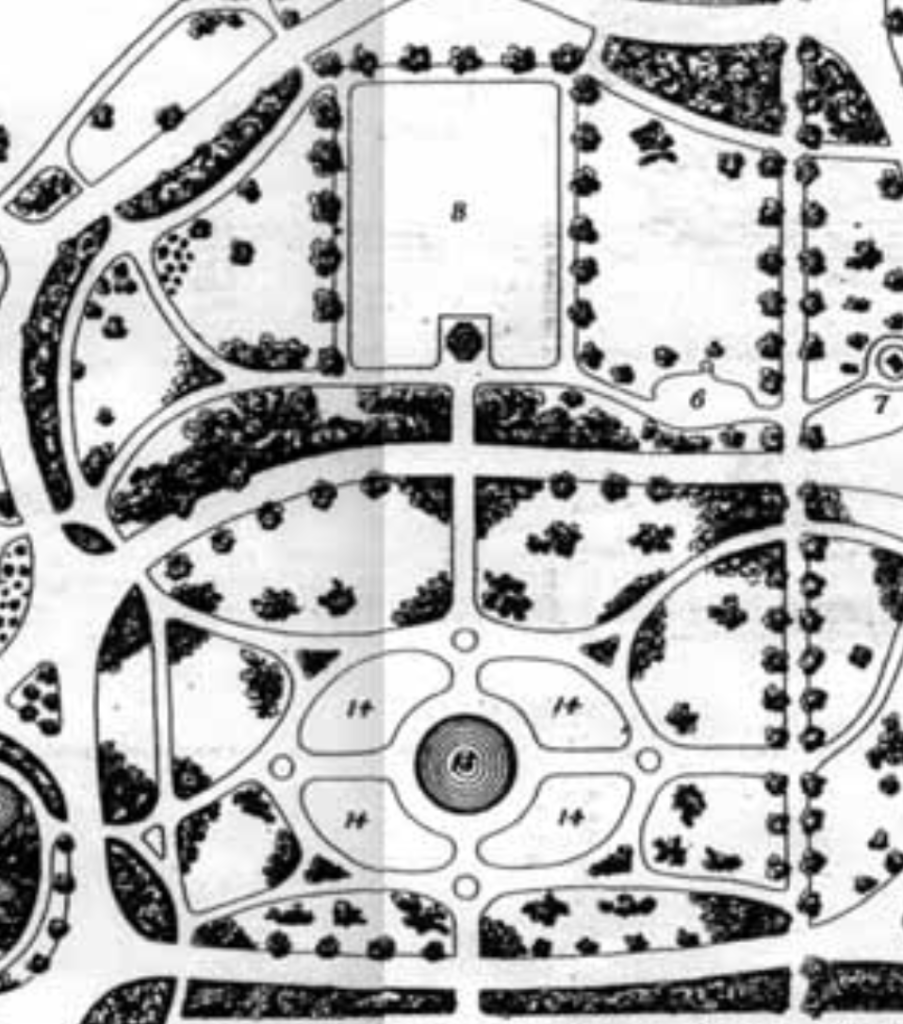

On All Nations Day, the Irish and Germans also held ceremonies and planted trees. A. Bleecker Banks, in his book recording the Albany Bi-centennial celebration, wrote: “After the Germans had concluded their exercises, the colored citizens proceeded in a body to where their elm tree was to be planted. It is on the same plot, a few rods from the German oak. (We learn from a much later article that the Burdett Coutts tree was “about 200 feet from the croquet ground, and a little west of north from the King fountain.” The German tree was “directly north of the plot set aside for the King fountain.”) Reaching the place the tree was placed in position, and a short but fervent prayer offered by the Rev. Mr. Derrick. “He thanked God that, as representative of a once down-trodden and despised race, they had the privilege enjoyed on that occasion.”

Then Thomas H. Sands Pennington, the noted African-American pharmacist who then resided in Saratoga Springs but was the president of Albany’s Burdett-Coutts Benevolent Association, had some things to say to the Mayor, Common Council and others of the Bi-centennial committee.

“What a wonder! What a crime! what a shame! Two hundred years ago the Dutch settled here to commence life in an independent way. After being here a short time, by trading with the Indians, who were the aborigines of the country, they became rich, and like all others thought they must have servants, and not being able to make any out of the American Indians, they sought other fields to procure the requisite laborers. After a short time Africa was proposed by some inhuman, although Virginia had already commenced the African slave trade.

“This method of involuntary servitude was carried on in this state until about sixty-eight or sixty-nine years ago, when the legislature of the state abolished the diabolical system of slavery. This, however, in one sense was true, but taking into consideration the many disadvantages that the descendants of Ham labored under, on account of color, and their former condition, we might almost as well have remained as we were. But the bi-centennial has brought about a great change. To-day, that once persecuted race, meets here on one broad platform, and independent with all nations, we have met for the purpose of commemorating the settling and to perpetuate the celebration of the bi-centennial. And we, as a part and parcel of this great republic, in common with others, purpose to plant an elm, with appropriate tablet attached, to show our affiliation with and approval of this movement.”

More on that tablet in a while.

After Pennington spoke, Robert J. McIntyre, identified as the chairman of the Colored Citizens’ association, accepted the tree from Dr. Elkins. In his remarks, he brought up some controversy about the establishment of Washington Park around 1871 on what had been the State Street Burying Ground; burials had just about stopped there by the Civil War, following Albany Rural Cemetery’s opening in 1844. The burial grounds were quite near where the trees were being planted.

The likely location

In 1876, just 10 years before the bi-centennial, although the burial grounds were gone, the area now taken up by the King Memorial Fountain was still occupied by two blocks of houses, from Knox Street to Snipe Street.

By the time of the Bi-centennial, those were gone, apparently, and Banks referred to that site as set aside for the King Fountain, which was first commissioned in 1878, but not actually completed until 1893. The croquet grounds were just north of that area, delineated by Hudson Avenue, as it was no longer named by the time of the 1891 map that clearly shows the area where the trees were likely to have been planted, north of the King Memorial Fountain area but below the croquet grounds:

Robert J. McIntyre’s Remarks

It’s not clear what McIntyre’s specific complaint was, though it is known that while about 14,000 graves were moved to Albany Rural Cemetery, not all were. The African American section was poorly documented, and it’s easy to imagine that removals to the new cemetery were less than complete. So it is possible that is the basis for some of McIntyre’s remarks, which were as follows:

“Dr. Elkins: As the chairman of the Colored Citizens’ association of this ancient and honorable city, it affords me pleasure to be the Albanian to whom the duty of the receipt of this tree from your hands should fall. You have spent the greater part of your life — now well up in the limit mentioned in Scripture as the time allotted to man — upon this part of the great State of New York known as Albany. When this place was but a wyck, or place of rest, as its name implies, there were among its inhabitants many people, mainly Germans who, though not the first to settle in this new world, still had foresight enough to sail up the Hudson in search of a new land flowing with milk and honey. Time will not permit a complete recital of the history of this our native city at this time, still, as you have stated, many years ago the African race which we, in part, represent, were found here serving as servants to the farmers having secured these rich lands from their original owners, the Mohawk tribes of Indians, and were proceeding to till its soil and improve it in every manner till it has reached so near a state of perfection as you find around and within its borders to-day. It is not my purpose to undertake to relate a history of this city or our connection with it; yet, I desire to say that in answer to those ignorant negroes who were anxious to know of me the color and style of our flag, I point them with pride to the starry flag, whose bright stars and broad stripes float a warning to all who train under or claim any other, and wish to tell them that in Africa, where all of our forefathers came from involuntarily, there was no civilization, no education, no houses and no flag, and that having served and fought and bled and died on America’s shores we, too, have a right to feel at home under its flag, which is our flag, and though we appear to-day in line as colored people, we are the second best Americans, and I am proud to say, Albanians.

“I notice that the present of this tree, whilst it marks an era in the history of Albany, is actually presented to the mayor, aldermen and commonalty of Albany. I accept it, therefore, and feel sure that its future welfare will exemplify in a strong degree some of its characteristics, foremost of which is its sturdiness. We, like this elm tree, have come here to stay. Our German friends have here erected one to mark their part in the celebration of the two hundredth year of our city’s birth. To them I say in closing, that for courtesies extended to us in this Bi-centenary, we return thanks. We know them as a noble, generous, hospitable, loyal people, and I add the hope that this fresh bond of reciprocal union between them and us may soon tie us as firmly together as the ivy does the tree ground which it loves to cling. I cannot let this day pass without calling to your minds a fault in connection with this park. Within this piece of ground many of us have shed many bitter tears upon the graves of loved ones. In my own time I have followed more than a dozen relatives to their graves, and here in sight of this place stands the largest tree within this park, an elm at that, and it was planted by my mother when it was but a switch about fifty years ago. Joining with you in the hope that this tree may grow to be so large as to attract attention, I thank you for the patience with which you have listened to my feeble remarks.”

A parade followed. “The colored citizens had a delegation in this division. They were members of the Burdette-Coutts [sic] Society, and rode in carriages. An elegant banner, presented by the ladies, was displayed.” In Banks’s history, the French groups, acknowledged as very small in number in Albany, received five paragraphs of description; the Irish who followed received six. The Italians, flogging the Columbus myth, received only a single paragraph but even that was much longer than this blurb the Black citizens were honored with.

So, what happened to the plaque?

So, there was the matter of a tablet or plaque to commemorate the tree. On April 8, 1893, the Times-Union ran an article titled “For Colored People / Commemorating the Planting of the Elm.”

“While seven years have not yet passed since the bi-centennial celebration in this city, there are but few people who will remember that during that memorable week three trees were planted in Washington park — one by the Irish societies; second, an oak by the German associations, and the third, an elm by the colored people.”

The article then introduced some confusion:

“About that time the monumenting and decorating committee had procured from Mr. Peter Kinnear the bronze tablets to be set on the stone to be used as monuments; and the Coutts society agreed that at some future time similar monument and tablet should point out the elm.”

In looking at Banks’s account of the bicentennial celebration in 1886, we find that the Decorations and Monumenting Committee of the celebration had made recommendations and provisions for four evergreen arches to represent the gates of the old city; nineteen granite slabs with bronze tablets; five bronze tablets to go on buildings; five bronze tablets noting old street names; and “decorations,” meaning further plaques, for the City Hall, City building, Schuyler corner, Pemberton corner, Schuyler mansion, and the Manor house in Albany, the Manor house in Greenbush, and “other ancient houses.” There were 42 plaques in all created for the Bi-centennial, but it does not appear (from Banks’s account) that any were provided for the commemorative trees planted by the Irish, German or Black societies. It’s not clear whether Kinnear’s monuments had anything to do with the trees, although that’s what the Times-Union implied. So while the Burdett-Coutts society committed that they would provide their own commemorative plaque, some seven years later it still had not been done.

“The elm thrived, has grown hardy and gives evidence of becoming quite a tree in time,” the Times-Union reported. But a marker was promised to be put in place soon.

“Their hopes and works will soon be fruition for stonecutters are already at work hewing out the block. The marker will contain the following inscription:

‘This tree was planted by the Burdette [sic] Coutts association in behalf of the colored citizens of Albany, at the bicentennial exercises, 1886. Dr. Thomas Elkins, Chairman; Samuel H. Mando, John H. Deyo, Committee.’

“The stone block will be about two feet high and the tablet will be set in the stone. The work will be set up this summer.”

It wasn’t, and it’s not entirely clear why.

Earlier that year, in February 1893, members of the Female Lundy Society, an African American female charitable organization, held a meeting at which Dr. Elkins unveiled the bronze tablet that was to be “placed in Washington park to mark the tree planted by the colored citizens of Albany during the bi-centennial ceremonies.”

After the Times-Union article, on May 28, 1893, The Argus reported that the bronze had just been completed. “The inscription is in Roman letters, and the tablet has a frosted surface. It will soon be placed in position. The Burdett-Coutts association will be present, wearing their handsome new golden badges, with monogram letters. Dr. Elkins is chairman of the committee.”

Was the monument barred by the Park Commission?

But 1893 came and went without the monument being placed. So did 1894. On August 29, 1894, the Albany Evening Journal reported this fact in an article headlined “No Cemetery Appearance / Washington Park Commissioners Object to a ‘Tombstone’ in the City’s Garden.”

Well, that’s ironic. Another stacked subhead reads: “Application To Place It Alongside the Tree Planted by the [Burdett-Coutts] Association in 1886 Not Acted Upon — The Memorial Tablet Ready and Its Custodians Waiting for a Favorable Reply to Place it in Position.”

“A handsome bronze tablet resting on a base of unhewn granite [dimensions unclear] inches in size at the top has lain in a barn for a whole year because permission cannot be obtained to place it in Washington Park.The tablet and stone were made for the Burdett-Coutts Benevolent Association of this city by Haight & Clark. The association is composed of colored men and there is much feeling among them because so much time has elapsed since they made application to be permitted to place the tablet in the park.

“In the year of Albany’s bicentennial – 1886 – the Burdett-Coutts Association planted an elm tree in the park just west [sic] of where the King fountain now stands and about 30 feet from the road. This was carried through by Dr. Thomas Elkins, Samuel H. Mando and John H. Deyo, and no objection to the planting of the tree was made at the time by any of the park commissioners. The tablet is intended to commemorate the planting of the tree. It is decidedly ornamental. The inscription is in raised letters and it reads:

‘This Tree was planted July 23, 1886 by the Burdett-Coutts Benevolent Association of Albany, N.Y. In behalf of the colored citizens of this city. Thomas Elkins, Samuel H. Mando, John H. Deyo, Committee.’

“John H. Deyo is a night watchman at the state capitol and has been the spokesman of the committee. A ‘Journal’ reporter found him last night. Mr. Deyo said that he called upon one of the park commissioners about a year ago and made application to have the stone placed beside the tree in the park. The commissioner, he says, replied that they did not want to make the park look like a cemetery, and added that there would be some objection to the placing of the stone. Nevertheless, Mr. Deyo says, the commissioner promised to bring the matter before the board.

“Since that time the colored people have heard no more about the matter, except, of course, they know the park commissioners have not given permission to place the tablet. Owing to the long silence, Mr. Deyo has been of the impression that the desired permission had been denied.

“Mr. Dudley Olcott, president of the park board, was seen by a ‘Journal’ reporter. He said that he did not remember any such proposition coming before the board at any time during the past two years. He was decided on this point.

“As to the possible objections that might arise in regard to placing a tablet in the park, he declined to be interviewed.”

So, we’re left with the uncomfortable question of whether this plaque ever made it into the park in the first place. If it did, what ever happened to it? If it did not, well . . . why? Was it really a concern that the park, which had been built in a cemetery, not look like a cemetery? Or was there more to it? Unfortunately, the trail of the plaque runs cold.

As does the trail of the tree itself. We find no further mentions of it in later years. It would be natural to assume that it could have fallen to Dutch Elm disease, which first hit the US in 1928 but really had devastating spread in the 1950s and 1960s, essentially defoliating our leafy cities. And it may well have been the case. But in 1897, just 11 years after the tree was planted, the Times-Union was reporting on the devastation being caused by the elm tree beetle, “which is destroying nearly all the shade growth in the city.”

Haight and Clark

Just as an aside, it seems a little odd that the Burdett-Coutts Association had to go to another foundry other than Peter Kinnear’s – after all, his seems to have cast all the other markers placed in the bicentennial year – but the article above indicates the final casting was by Haight and Clark, which was a foundry on Pleasant Street, just off North Pearl and immediately adjacent to the rail lines.

Leave a Reply