I started out to write a little bit about Dr. Thomas Elkins, one of the most remarkable and accomplished African American residents of Albany. I was challenged by two things: there is so much to say about Dr. Elkins, and much has already been written elsewhere. I may well come back to him, but he is a big topic.

But in researching Dr. Elkins, I found another Black Albanian who has not gotten nearly his due: Thomas H. Sands Pennington. Frequently identified as T.H.S. Pennington, his life and accomplishments were truly remarkable, and all the more so for having succeeded in the face of the blatant discrimination of the time, becoming, despite that, a highly regarded pharmacist in Saratoga Springs. He was connected not only to Dr. Elkins, but to Albany hotelier Adam Blake, the Burdett Coutts Benevolent Association, and to escaped slave and abolitionist James William Charles Pennington.

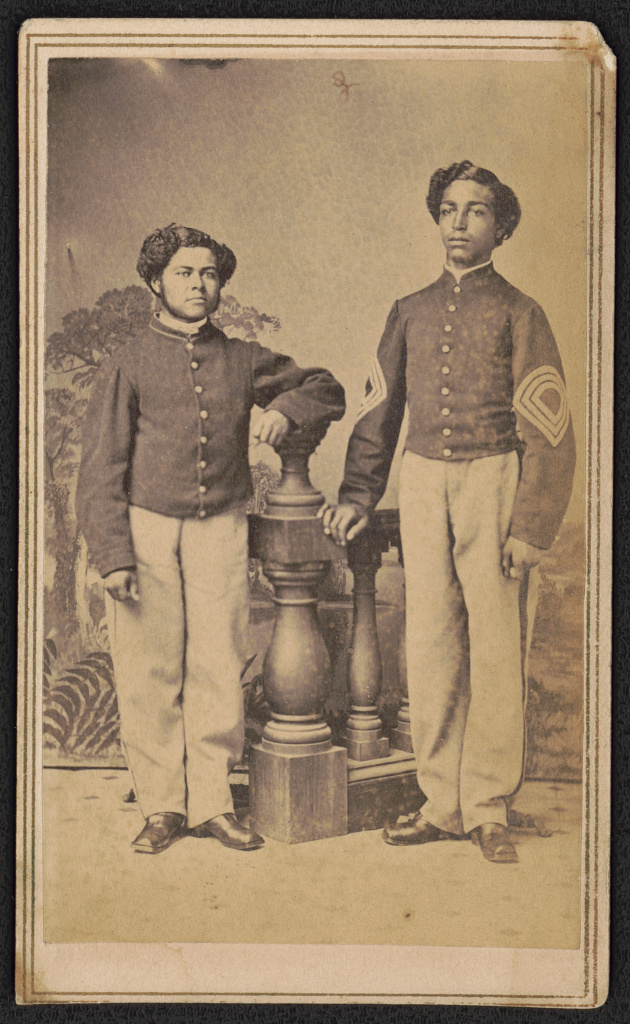

I’m now tremendously grateful to Reginald Pitts for locating this Library of Congress photograph of T.H.S. Pennington, serving in the Civil War as a Hospital Steward. He is standing to the left of Sergeant Major William L. Henderson. Both were serving in the 20th U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) Infantry Regiment:

T.H.S. Pennington received his training with Dr. Elkins in Albany, and worked in the city for a time as well as leading one of the Capitol City’s Black benevolent societies. He also worked in New York City before and after the Civil War, and spent some of his later years in Troy. But from about 1867 to 1890, Pennington was a fixture in the resort city of Saratoga Springs.

James W.C. Pennington

I can’t begin to tell the story of James W.C. Pennington — for that, I would recommend “American to the Backbone,” by Christopher L. Webber (2011). An abstract begins:

“At the age of 19, scared and illiterate, James Pennington escaped from slavery in 1827 and soon became one of the leading voices against slavery prior to the Civil War. Just ten years after his escape, Pennington was ordained as a [minister] after studying at Yale and was soon traveling all over the world as an anti-slavery advocate. He was so well respected by European audiences that the University of Heidelberg awarded him an honorary doctorate, making him the first person of African descent to receive such a degree.”

It is Webber’s book which says that Pennington adopted Thomas H. Sands:

“James Pennington returned to New York not only with a new wife but also a newly adopted four-year-old son. Thomas H. Sands Pennington was the child of Sarah Blackstone Sands, who had died on March 28 at the age of 31 and on her deathbed asked the Pennington adopt her son.”

It was in 1848 that Pennington returned from Hartford, CT, to New York City with a new wife, Almira Way of Hartford, and a new son, Thomas H. Sands Pennington. This and other records seem to indicate that Thomas was born about 1844. So from this we know the name of Thomas’s mother; we don’t know about a father. A Raphael Sand, a Hartford hotel worker, lived at one point in a residence where Pennington had earlier lived in Hartford (according to Webber), and, interestingly, Rafael J. Sands, a baker, later lived with Thomas in Saratoga, but there is no certainty that he was his father, and it seems to me more likely he was an uncle. We’ll get to that.

From his birth in 1844 until 1863, I have found nothing in the records about the life of T.H. Sands Pennington. He first appears in the records I’ve been able to view in 1863, in Albany, where he registered for the draft. Listed as Thomas Pennington, age 22 (as of 7/1/1863), he gave his race as “colored,” and reported that he was an unmarried clerk who had been born in Connecticut. He was living at Broadway, at the corner of Clinton Avenue. But by then, he was already long trained in what would be his profession: pharmacy.

Training as a Pharmacist

For these next details, I’m beholden to a Nov. 1897 article on “The Negro in Pharmacy” that appeared in “The Druggists Circular and Chemical Gazette.” It’s that article that gives some of Pennington’s timeline and connection to Dr. Elkins. It said that Pennington “received his lessons in the rudiment of pharmacy from Dr. Thomas Elkins, of Albany, himself a colored man, in 1854-55.”

He went to New York City after 18 months of training and filled in for an owner of a black-owned store at the corner of Grand and Mercer streets known as Miller & Vosburgh; but when Mr. Miller returned to health, “Mr. Pennington was obliged to look for another position.”

He returned to Albany and joined the pharmacy of H.B. Clement at the corner of Broadway and Clinton., where Clement was in business with various partners for decades. That address was Pennington’s residence when he registered for the draft; it’s entirely possible he lived on the premises of the pharmacy.

As a clerk, Pennington was mentioned in the Morning Express of August 16, 1861, as having been passed a counterfeit bill by one of a group that was operating across New York at the time, passing bills that were counterfeits of the Judson Bank of Ogdensburg. (Recall that before the Civil War, banks issued their own currency.) It’s worthy of note that the event happened between 9 and 10 o’clock at night – a time when pharmacies today are nearly all closed.

“Here [with Clement] he remained for about six years, when, in December, 1863, he offered his service to the Union League Club, of New York, who assigned him to the position of hospital steward for the Twentieth United States Colored Troop.”

Civil War pension files and Veterans Schedules confirm that Pennington served as a hospital steward in the 20th United States Colored Infantry. He enlisted Feb. 9, 1864.

Saratoga Springs

The Druggists Circular article says that after the war, Pennington worked in the pharmacy of Philip A. White of New York for “a couple” of years. White was an African American pharmacist who was located at the corner of Frankfort and Gold streets, an area now largely occupied by ramps to the Brooklyn Bridge.

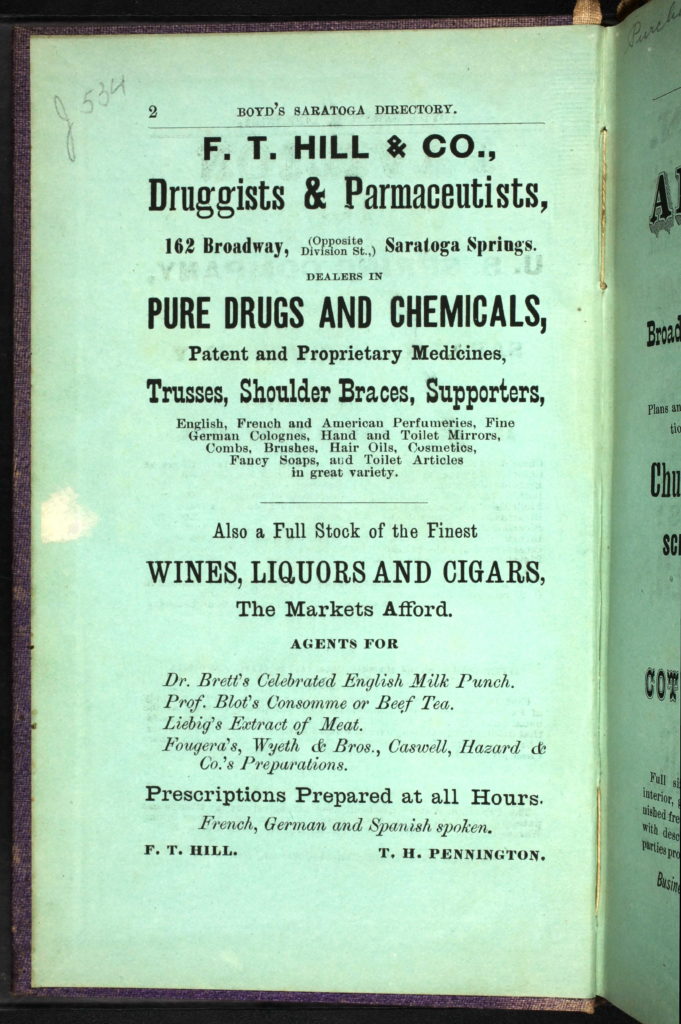

Pennington went to Portland, Maine, to start his own store, but “not being satisfied with the outlook” returned to New York State, accepting a position as an “extra clerk” for the season of 1867 with F.T. Hill & Co. of Saratoga Springs. And it was here that he would settle for many years. “His entrance into the business at this fashionable summer resort was liberally criticized, many thinking that it would injure the firm by whom he was engaged, and others considering that it was a shrewd business move to get the good will of the many negro servants employed about the hotels.”

The article also tells stories of how Pennington was able to win over prominent clientele with his abilities and attitude — stories no doubt written by Pennington himself, or someone very close to him who provided this information for the article. One involved a former Governor of South Carolina who, after having Pennington “paint” his finger joints with tincture of iodine, begrudgingly acknowledged, “You do know something.” Pennington said, “I informed him that there was no charge for the drug or for service rendered, but that I would be pleased to have the patronage of himself and family while they remained at the village. He replied emphatically. ‘You shall,’ and he kept his word.”

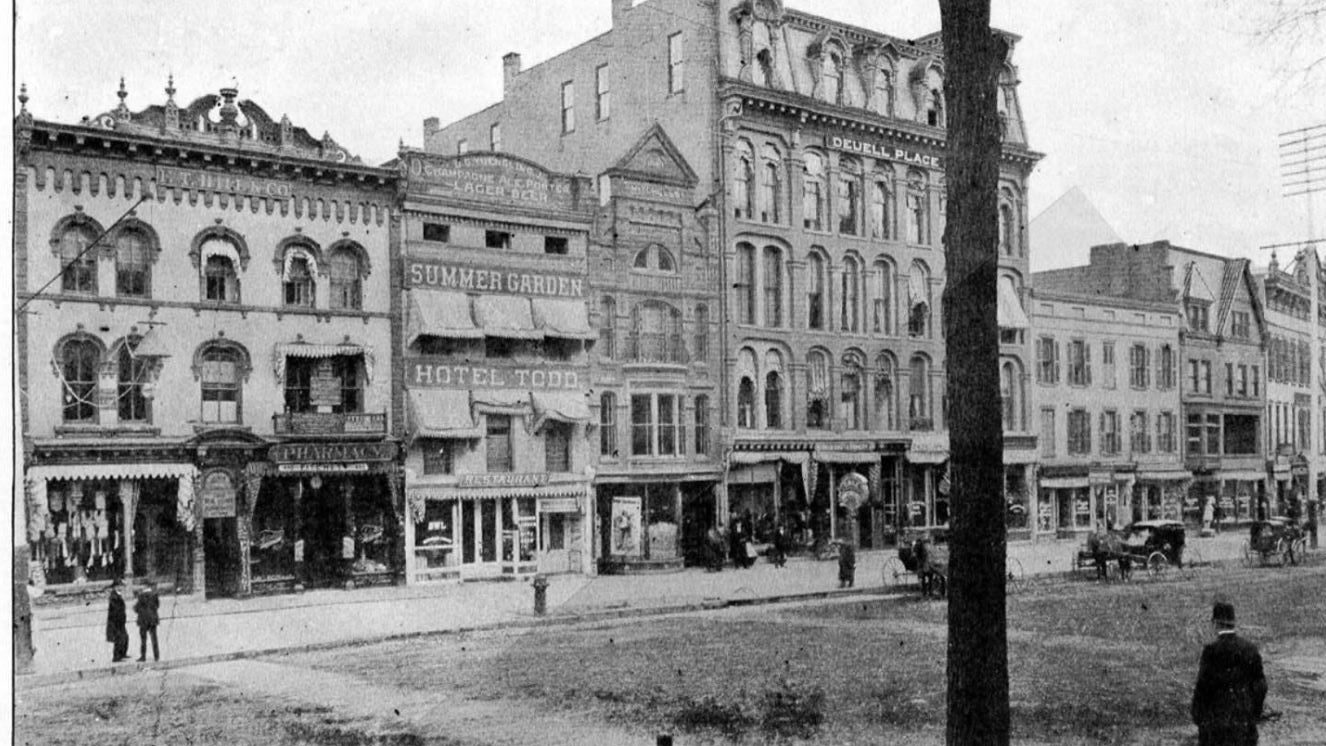

The story further tells of an ex-judge of Saratoga County, whose denunciations brought a rebuke from the pharmacy owner, Franklin T. Hill, who is reported to have said, “I employ those whom I consider competent and am pleased with, to assist in conducting my business. If you do not like them, you have the privilege of going elsewhere.”

(While it doesn’t contain much on Pennington himself, I strongly recommend Myra B. Young Armstead’s 1999 book “Lord, Please Don’t Take Me in August,” which details Black life in the resort towns of Saratoga Springs, New York, and Newport, Rhode Island, demonstrating how resorts brought their own advantages and disadvantages for Black residents, some of whom were attracted by seasonal work and some of whom made these places their homes year-round.)

Owning His Own Pharmacy

The Druggists Circular article indicates that Pennington remained with Hill and its successor until 1880, when he purchased the business on his own. “For ten years he conducted it successfully, but in 1890, owing to a combination of unfavorable circumstances, he surrendered.”

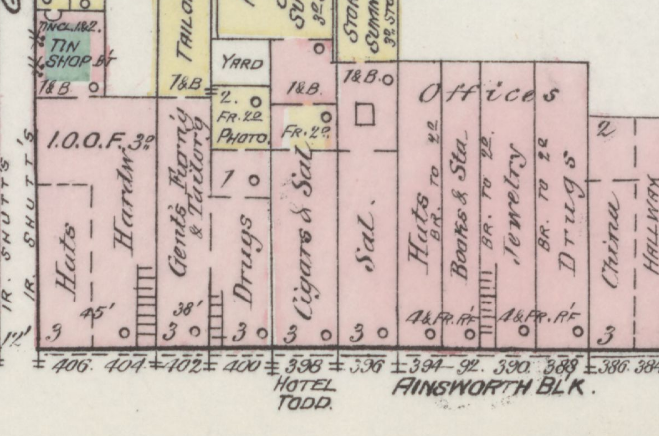

Digging a little bit into that — there must have been a special relationship between Franklin T. Hill and Thomas H. Sands Pennington. Franklin T. Hill was born in Woodbury, Vermont, in 1819, and lived in Saratoga for about 30 years until his death in March 1875. He never married, and accumulated “a fortune of about $60,000.” Hill had a partner, listed in his advertising, Dr. John L. Perry, Jr. That partnership dissolved effective April 1, 1873, “by mutual consent, John L. Perry, Jr., retiring from the firm. The business will be continued by F.T. Hill, J.S. Hill and T.H.S. Pennington, who have formed a copartnership under the style and firm name of F.T. Hill & Co.” at 162 Broadway. In the next directory listing in 1874, the company is listed as “Hill F.T. & Co. (T.H. Pennington), druggists, 162 Broadway.”

(It’s just a side matter, but an interesting one, that Franklin T. Hill was an executor of the will of John L. Perry, Sr. Interesting, because in 1874, John L. Perry, Jr. opposed probate of that will on the ground that his father was not of sound mind, and that the execution of the will was obtained by fraud and undue influence. Perhaps that family intrigue led to the dissolution of the partnership.)

So Pennington was a partner in the pharmacy business by 1873, about 6 years after coming to Saratoga. When Hill died in March 1875, T.H.S. Pennington was an executor of Hill’s estate.

We find Pennington that year listed as in charge of the prescription and family order department of B. Schermerhorn, “successor to F.A. White,” at 400 Broadway in Saratoga. That’s a bit confusing, in addition to getting the name wrong, clearly. Armstead’s “Lord, Please Don’t Take Me in August” says that Pennington was the sole proprietor by March 1875, that he was listed as manager of the pharmacy in city directories in 1875 and 1876, but was out of business by July 1876 (according to R.G. Dun and Co. credit ledgers). She writes that Dr. Perry’s assistance enabled Pennington to reopen the pharmacy in 1880, and “for the next ten years, he ran the drugstore, which clearly catered to a mixed clientele.”

So exactly how he progressed through the 1870s isn’t especially clear, but once the business was under his own name in the 1880s, he did a lot of advertising in The Saratogian, particularly for patent medicines, especially from 1883-85.

The Burdett Coutts Benevolent Association

Phelps’s “The Albany Hand-Book: A Strangers’ Guide and Residents’ Manual” takes an encyclopedic approach to explaining Albany of the 1880s, and in the 1884 edition, it has an entry on “African Race,” and that entry said that under the census of 1880, “there were 1056 negroes in Albany. Many are employed as waiters at the hotels and on steamboats, etc.; some are well-to-do, and they have their representatives in the learned professions.” It then listed institutions “peculiarly their own,” including the Burdett Coutts Benevolent Association.

Joseph Aubin Smith was an African American who worked for years in the hotel business, including a year as superintendent of the Kenmore Hotel working for Adam Blake. According to Smith, the Burdett Coutts Benevolent Association came about because of his stay in London, where he provided information “to parties of Americans going on the Continent.” While there, he stayed with a family named Terry, and Mr. Terry had been in the service of Baronesss Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts for 14 years. The Baroness was frequently called the world’s greatest philanthropist. Smith tells his story in “Reminiscences of Saratoga: Or, Twelve Seasons at the “States.”

“On returning to America I spent a social evening with an esteemed friend at Albany; and the conversation drifted to the subject of forming a society, the object of which should be charity and benevolence, with special reference to extending a helping and in time of sickness and death . . . Looking around for a suitable name, I suggested that of Lady Burdett Coutts, which was unanimously adopted, and which has remained the name of the society to the present time.”

The organization was founded in 1879, coincident with the time Smith went to work as superintendent of the Kenmore Hotel, owned by Adam Blake, probably the most prominent African American businessman of his time. It isn’t clear precisely when, but T.H.S. Pennington became its president, and was re-elected to that position at least once, in 1884. The Saratogian of Feb. 28, 1884 wrote:

“The Burdette-Coutts [sic] Benevolent Association of Albany, of which our esteemed townsman, T.H. Sands Pennington, is the president, held a public installation of officers in the Jackson corps armory last Thursday evening. This association was organized in 1879, for benevolent, charitable, literary and social purposes, and was incorporated under the laws of the state of New York in 1880. The installation at which Mr. Pennington entered upon his duties, was the first public one ever given. A programme consisting of musical and literary exercises was rendered, after which dancing and refreshments filled out the balance of the evening. Mr. Pennington returned home Friday morning and reported a capital time.”

Thus far I haven’t found much more on the work of the Burdett Coutts Benevolent Association; it’s worthy of considerably more research. On the one hand, it was a prominent enough Black association to gain occasional notice in newspapers and guidebooks; on the other hand, like most Black associations, that notice was scant and infrequent.

The 1880s

In the 1880 census, T.H.S. Pennington is listed in Saratoga. He listed his age as 34 (which, if true, would mean he was born around 1846 instead of 1844); wife Isabella J.B. was 33. They had a daughter, Emily Isabella, who was 5 years old. At the next residence was Rafael J. Sands, age 63, a baker, and Emily A. Sands, 53. (All were listed as mulatto, using the racial distinctions of the time.) T.H.S. reported his father’s birthplace as Cape De Verde Islands (and his mother’s as Connecticut, where he was born); Rafael’s birthplace was also Cape De Verde Islands, a center of the Portuguese slave trade. We haven’t learned more about Rafael, but speculate he was likely an uncle.

Courtesy of Yale University’s Randolph Linsley Simpson African-American Collection.

Pennington appears to have been prosperous throughout the 1880s. As mentioned, he frequently advertised in The Saratogian in the mid-1880s for his patent medicines, including Pennington’s Norwegian Troches (lozenges), Odontine (for teeth), and a variety of insecticides.

He was even given a writeup in 1888’s “Empire State: Its Industries and Wealth,” a useful compendium about businesses throughout the state. Here is what they had to say:

“T.H. Sands Pennington, Pharmacist, No. 400 Broadway.— In elegance, reliability and extent of trade the pharmacy of Mr. T.H. Sands Pennington at No. 400 Broadway, occupies a leading position at Saratoga Springs. The career of the house since the accession of Mr Pennington to the proprietorship in 1880 has been prosperous and successful, and under enterprising and efficient management the volume of transactions has steadily increased with each succeeding year. The store is spacious in size, and all its appointments are handsome, attractive and appropriate, no pains or expense being spared to make it as complete as possible in every feature. A very large stock is carried of pure drugs, chemicals and pharmaceutical preparations, essences and extracts, wines and liquors for medicinal purposes, toilet articles and fancy goods, druggists’ sundries of all kinds, and, in fact, everything kept in a first-class establishment devoted to this trade. The proprietor makes his purchases from the most reputable sources, approaching first hands only, which is duly appreciated by all who patronize this house. The prescription department is carefully and systematically directed, and the limit of precision and safety is reached in every case. Mr. Pennington is well and favorably known in this community as an experienced and accomplished pharmacist. He is a member of the American Pharmaceutical Association, and we cordially commend his establishment to visitors in Saratoga as worthy of every confidence.”

We know nothing of the arrangement with Dr. John L. Perry that put T.H.S. back into the pharmacy business in 1880, but it would appear that the failure of that arrangement — perhaps a simple inability to pay back a loan — ended it. On April 23, 1890, the Schuylerville Standard reported that “the drug store of T.H. Sands Pennington, was closed Thursday morning, at Saratoga, by Deputy Sheriff Frier, on an execution of $6,338 in favor of Dr. John L. Perry.” In January 1891 the Pharmaceutical Record reported that “Walker & Fichett succeed to the business of T.H. Sands Pennington. W.H. Walker has been in Saratoga Springs for a dozen years or more, while I.P. Fichett was formerly in Poughkeepsie, though for a year past in Saratoga.”

His Final Years

Following those “unfavorable circumstances,” the 1897 article from the Druggists Circular reports that Pennington spent a season as an assistant to C.F. Fish in Saratoga, and “when the season closed he secured employment with H. Gnadendorff of Troy. He remained at this place until the death of Mr. Gnadendorff last year.” That made us pleased, because Hermann Gnadendorff, a Prussian native whose business was first in Schenectady and later in Troy, had a particularly splendid stained glass transom window that still decorates his former building in Troy, and now we can imagine a physical location where Pennington spent some years of his life. In 1892, while working at Gnadendorff’s at 14 Second Street, his home was at 69 Ferry Street in Troy. (That building at the northwest corner of Third still stands.) In 1894, he was living at 188 Ferry; in 1896, he was listed at 1849 Fifth Ave., a spot that is likely now the location of the Firestone service station just south of Congress Street.

Following Gnadenforff’s death, Pennington went back to C.F. Fish in Saratoga, “where he remained until taken sick last summer [1896]. When last heard from he was still unable to return to work,” at age 52. He had filed for invalid status under his Civil War service on May 23, 1891, so it’s entirely possible he was suffering diminished capacity in some form throughout the 1890s.

Although he may not have been working, in 1899 he wrote a paper that received notice in the journal The Western Druggist. Titled “Economy in the Kitchen of Pharmacy,” it was noted by the Committee on Practical Pharmacy of the American Pharmaceutical Association at the annual meeting Sept. 1899.

[We simply have to note that the annual address that year delivered by the association president was on the topic of – not making this up – the white man’s burden, “particularly in so far as the new relations between the United States and the Philippine islands are concerned; and American pharmacists have a share in this burden of civilizing the far-off heathens by sending them medicinal supplies, teaching them true pharmacy, and by establishing among them pharmacies of modern type. In this way, the speaker thought, not only would this country profit financially, but we would rid ourselves of the surplusage in our ranks . . . Before many years a great number of American pharmaceutical graduates will be found doing business in the Philippine and West Indian islands.”]

Thomas H. Sands Pennington died March 5, 1900 in Saratoga, “after having submitted to an operation for hernia. He was for more than a generation engaged in the drug business in Saratoga, and for a long time lived in Troy,” reported the Schuylerville Standard.

Pennington’s Own Words

For the final words, we return to The Druggists Circular:

While seeking employment as a junior and also in 1890-91 Mr. Pennington applied to many of the druggists in Third avenue and Sixth avenue, this city [New York], and also answered many advertisements.

“The character of my reception was varied,” he afterward said. “Some were curious, many were friendly, others were curt, and a few were insulting.”

In speaking of some of his experiences, Mr. Pennington says:

“As a clerk I always endeavored to treat those around me in a courteous and gentlemanly manner, and with very few exceptions it has been reciprocated.

“As manager and employer I have always received due consideration and have frequently received recognition from sources from which it was least expected.

“From the trade generally I have always received courteous treatment.”

Mr. Pennington thinks that the reason there are so few Afro-Americans in pharmacy is because they meet discouragement at the outset of their careers, which increases in proportion to their advancement. The negro is refused employment “because we think it will be detrimental to our trade;” or “our clerks might make it unpleasant for you.” Hence the man of ability seeks employment in other lines. Mr. Pennington has observed one thing, however, and that is where one negro has run the gauntlet and established himself as a pharmacist, it is much easier for others to get a foothold. He relies upon an always intelligent and discriminating public to see that every man is finally recognized according to his own worth.

I love all of your articles, and have learned so much about the more obscure parts of the Capital District’s history from them. I am especially interested in African American history, and you never disappoint. I am going to have to read up further on Mr. Pennington.

Thank you!

Hello!

Thanks for the detailed and informative post on Thomas H. S. Pennington! I was rather surprised when you stated that you hadn’t found a photograph or any likeness of Mr. Pennington, as I have been aware of one for quite a while. Mr. Pennington served in the Civil War as a Hospital Steward in the 20th USCT; the attached will show him standing (on the left of the picture) in his full uniform with Sergeant Major William L. Henderson, also of the 20th USCT . The provenance of the likeness is the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2016646171/).

I am a fan of yours, and when things ease up a bit, I will be heading up to the Capital Region and do some sightseeing. Your posts have been a great help, and I am happy to, in some small way, return the favor. Wishing you the best!

Thanks again.

Thanks so much! No, I never ran across that one in my searches, so I’m very grateful!

I was going to ask how you were sure which was which, but I’m going to assume it’s the the rather hard-to-miss sergeant major’s insignia. Wow is that large!