So how did Schenectady, a stockaded community, come to be unguarded at a time when it was known the French and their allied tribes were looking for opportunities to retaliate? The answer is unsurprising to any New Yorker: politics.

In 1689, New York and New Jersey were governed as part of the Dominion of New England, under Sir Edmund Andros. His Lieutenant Governor, Francis Nicholson, tended to New York and New Jersey. To say that Andros and Nicholson were widely despised would not be an overstatement; Nicholson regarded the colonists he governed as “a conquered people,” even 24 years after England had gained control of New Netherlands. Even in New England, where no conquering had taken place, Andros was hated. As soon as news arrived in 1689 that the Glorious Revolution had deposed King James and that William and Mary now ruled Britain, a Boston mob arrested Andros and other officials and restored their former government.

In New York City, Nicholson had word of the Boston uprising on April 26, 1689, but tried to keep it quiet. About the same time, he learned that France had declared war on England, and most troops at his disposal were away in Maine, protecting border communities. On May 30, the local militia seized on an insult by Nicholson as a cause for open revolt. They relieved Nicholson of the keys to the powder magazine and raised merchant Jacob Leisler to command; they then declared they would hold Fort James (at the tip of Manhattan) on behalf of William and Mary until a new governor was sent.

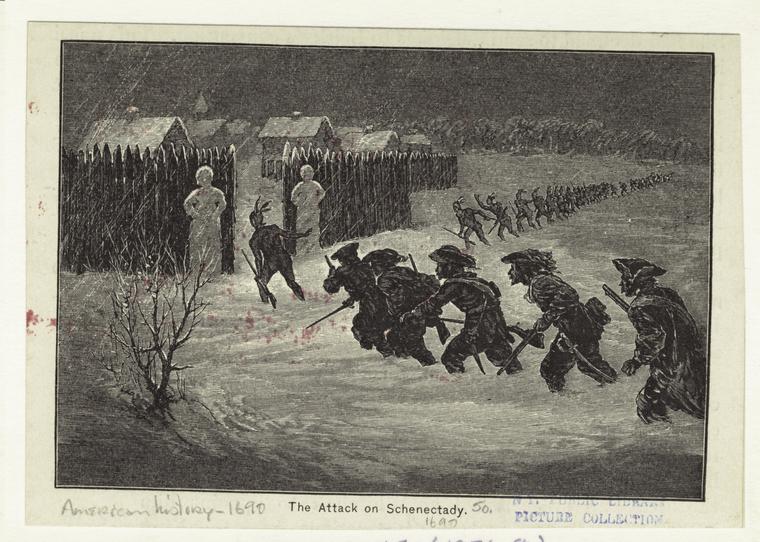

Leisler’s rule was not accepted by all. The city fathers of Albany proclaimed the rule of William and Mary and established a governing Convention of their own, which refused to recognize Leisler. However, nearby Schenectady, which had been in some formof friction with Albany since its founding, was much more divided on the issue, and so Leisler focused efforts there on building support, offering them rights of trade they had always been denied by Albany. Differing accounts, mostly after the massacre, may make it impossible to know what really happened, or why none of the 24 soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Enos Talmadge, of Capt. Jonathan Bull’s Connecticut militia company, were guarding the gates that night. It is said that Leisler’s supporters in Schenectady derided the counsel of Captain Sander Glen and his brother Johannes, who lived across the river, and that they also disdained the militiamen, who were opposed to Leisler. Unwanted, the militia men may have simply kept to themselves. (Some years later, despite the lesson of the massacre, the community’s disdain for the militia would spark a mass desertion among the ranks.) The only thing all could agree on was sending a scouting party north to Lake George to see if there were any advancing French; given the vastness of the wilderness, it isn’t surprising that a scouting party of 40 Mohawks sent north to look for French invaders did not happen to encounter the enemy force, but it may have been the small community’s only line of defense.

Albany leader Robert Livingston later claimed that the residents of Schenectady would not listen to the magistrates of Albany, and “neither would they entertain ye souldiers sent thither.” Leisler, in turn, blamed Albany. In either case, whatever protection there was proved entirely ineffective. And everyone agrees that the gates were open that night. Tradition has always held that they were guarded only by snowmen.

So, a king is deposed, France and England are at war, a colonial militia seizes power, two communities continue their in-fighting, a gate is left unguarded . . . and 60 people are slaughtered in the night.