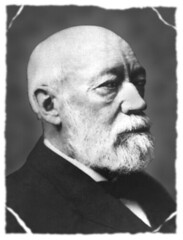

John Wesley Hyatt was born in Starkey, New York, on the west side of Seneca Lake on November 28, 1837. When he was sixteen, he went to Illinois and became a journeyman printer. He (and later, his brother Isaiah) came to Albany and worked in printing. His interest in invention is shown by his patent of a knife sharpener in 1861. The story goes that Phelan and Callendar, a major manufacturer of billiard tables in New York City, offered a $10,000 prize for the creation of a composition ball to replace ivory. Years later, in 1914, the New York Times related that Hyatt entered that competition in 1863, and that “it was by accident that Mr. Hyatt discovered the chemical product that has brought him fame the world over. He was accustomed to use collodion for cuts while working at the printing trade. One day a bottle of collodion overturned, and it was after watching the solidification of the collodion that he got the idea of making celluloid.”

Whether celluloid was invented in 1863, 1868 or somewhere in between, Hyatt filed for a patent in 1865 (granted in 1870), and continued working as a printer for several years, living at 32 Chestnut St. and later at 149 Spring St. He must have been working on business arrangements during that time. In 1867 Hyatt was with Osborne, Newcomb & Company, checker manufacturers at 795 Broadway. By the end of 1869 Hyatt had turned his invention into a number of commercial products, all being manufactured in Albany. In that year, the Osborne, Newcomb was sharing space with the Hyatt Manufacturing Company, making billiard balls, checkers and dominoes at 795-797 Broadway (now an empty urban field just north of Livingston Avenue). (Encyclopedia Britannica suggests the checkers and dominoes weren’t celluloid, but were a mix of wood pulp and shellac Hyatt developed prior to celluloid.) By the end of 1871, the billiard balls were being made by the Hyatt Manufacturing Company at 19 Beaver Street, just west of Broadway. His brother, Isaiah Smith Hyatt, took up the checker and domino business as the Albany Embossing Company, a few blocks south at 4 and 6 Pruyn St. The material was also apparently put to pioneering use in dental plates, by the Albany Dental Plate Company. (Despite numerous references to this company in the histories of celluloid, I find no reference to this company in the city directories of the time.)

There are numerous hints that all was not well with the finances of any of these companies. Even in the year in which Isaiah was listed in the city directory as President of the Embossing Company, the New York Times wrote glowingly of the enterprise and identified Robert C. Pruyn, of one of the most established families of Albany, as its head. 4 and 6 Pruyn Street was also home to the Albany Saw Works, an established firm run by Pruyn (“manufacturers of extra cast steel circular, mill, gang, cross-cut and other saws.”) The Times also spoke of embossing wood, not celluloid, and of the company having been burned out twice in the previous two years. One has to wonder whether those fires were related to a persistently reported quality of the new celluloid material – that it was explosive. The oft-repeated stories of exploding billiard balls are unlikely to be true, but it cannot be denied that cellulose nitrate was a dangerous material to work with, at a time when workplace safety was not a primary concern. (Hyatt’s later factory in Newark, NJ suffered 39 fires in 36 years, killing 9 and injuring 39.)

That same article in the Times, written at the very close of 1871, effused over the Hyatt Billiard Ball Company,

“who make billiard balls of a composition which, when colored, can hardly be distinguished from ivory balls, and which, in addition to many other advantages, are claimed to be much more durable. They certainly have this one superiority over ivory balls, that whereas ivory is always apt to be unequal in density, giving a tendency to irregular direction and to ‘wabbling,’ the composition balls have an unerring center of gravity from the mere fact of their being composition — every component part being thoroughly mixed and disseminated throughout the ball.” The Times went on to describe the manufacture of the composition balls: “These balls are composed principally of “gun cotton,” reduced to a fine pulp and molded. The other ingredients are as yet a secret, which the makers do not desire to make public. After molding, the ball is put in a globular press, and reduced about one-third in bulk. It is then put away to be dried. When partially dry it is put into a bowl of quicksilver to test the uniformity of its centre of gravity. If not true in its balance it is thrown aside; if true it is again pressed and again put on the shelf to be thoroughly dried before it is taken to the turner and the polisher. Three months elapse from the day of molding till the time when a ball is ready to be sent to purchasers. The balls cost about one-half the price ordinarily charged for ivory balls.”

The history of the company gets foggy from there. One account says that the Albany Dental Plate Company changed its name to the Celluloid Manufacturing Company and moved to Newark, New Jersey, in 1873. By all accounts, the Hyatts did move to Newark and developed new machinery and new uses for celluloid. In 1881 they founded the Hyatt Pure Water Company, and ten years later Hyatt established the Hyatt Roller Bearing Company of Harrison, New Jersey. He was even an early bio-fuels enthusiast, converting spent sugar cane into fuel. His patents also included a knife sharpener, a new method for making dominoes and checkers, a lockstitch sewing machine, a machine for squeezing juice from sugar cane (which led to the development of his roller bearing), and a new method of solidifying hard woods for use in bowling balls, golf stick heads and mallets. A series of advertisements extolling the company esteemed his roller bearing as vastly more important than celluloid:

Many millions of Hyatt Bearings are now manufactured annually. Their use has extended to practically every class of machinery and every form of transport where efficient, dependable bearing performance is demanded. They are operating in mammoth industrial plants – in mine cars and factory trucks – in farm tractors and implements – and in millions of motor cars and trucks.

Honored by the Society of the Chemical Industry with its Perkin Gold Medal (named in honor of the inventor of mauve) in 1914, Hyatt died at his home, Windermere Terrace, in Short Hills, NJ, on May 10, 1920.

A previous version of this article focused on the question of where the original Hyatt factory stood, and therefore where celluloid was first invented and produced. It’s still available here.