Once again, one of Albany’s Bicentennial markers is missing – and this one wasn’t even in Albany. The Bicentennial Committee listed the following text on Tablet No. 26:

Tablet No. 26 —Johannes Van Rensselaer

In bronze, 7×16 inches, set in the wall of the original mansion on the Greenbush banks. Inscription: “This Manor House, Built by Johannes Van Rensselaer, 1642.”

That refers to Crailo (previously called Fort Crailo, though never was it a fort). The building wasn’t built in 1642, and it wasn’t built by Johannes Van Rensselaer (although he did expand it). The text was actually expanded considerably before placement, as reported by the Argus in 1914, reading:

“Supposed to be the oldest building in the United States and to have been erected in 1642 as a manor house and place of defense known as Fort Cralo [sic]. General Abercrombie’s headquarters while marching to attack Fort Ticonderoga in 1758, when it is said that at the cantonment east of this house, near the old well, the army surgeon R. Shuckburg, composed the popular song of ‘Yankee Doodle.’”

We have no evidence that this rather wordy marker still exists – it doesn’t appear on the building or grounds, and email to Crailo on the topic was unanswered.

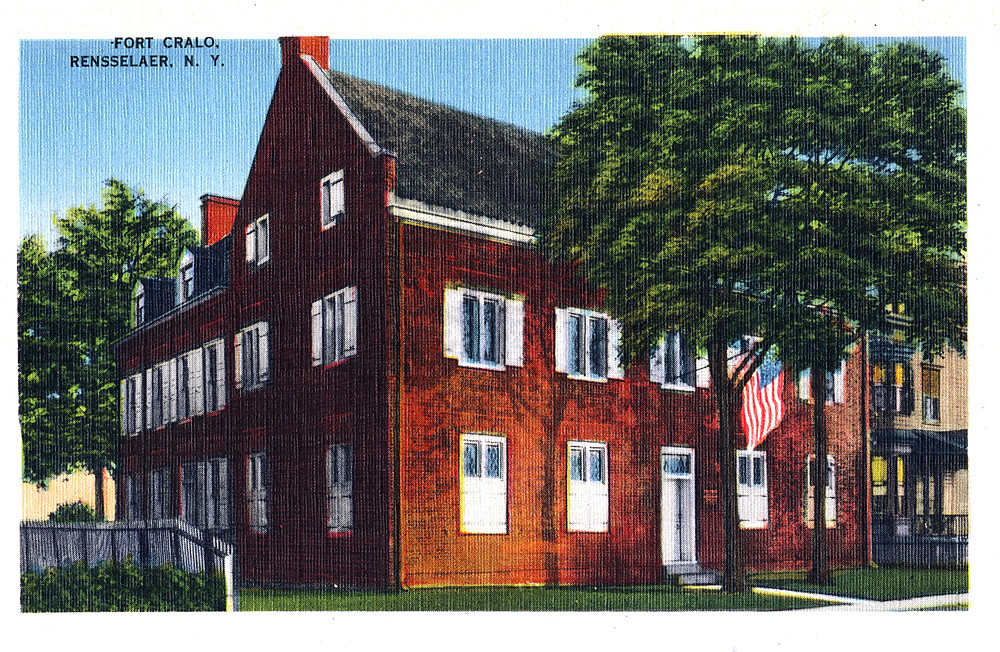

Crailo

The name Crailo seems to have been imported from Holland, meaning “Crows’ Woods,” according to Margaret Reynolds’ “Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley,” the only book we’ve used in our research that features a foreword by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“The patroon owned an estate southeast of Amsterdam in Holland, called Crailo (Crows’ Woods), and in the Greenen Bosch on the Hudson a farm was soon laid out which by 1661 had received the name of Crailo. A letter written by Jeremias Van Rensselaer in 1668 refers to: ‘a convenient dwelling-house’ on Crailo. From 1675 to 1678 this farm was occupied by the Reverend Nicholas Van Rensselaer (then director [of the Patroonship]), after whose death it was in the possession of his widow and her second husband, Robert Livingston, who rented it to a tenant.

“In 1685, by a formal agreement, Crailo reverted to the Van Rensselaer family in Holland and then in 1695, by the Settlement above mentioned in that year, it became the property of the fourth patroon, Kiliaen Van Rensselaer. When the latter received in 1704 from the English Crown confirmation of title to his great landed estate he made provision for his younger brother, Hendrick Van Rensselaer (born 1667, died 1740), by giving him the Greenen Bosch (inclusive of Crailo) and also a tract called Klaver Rak in what is now Columbia County, New York.”

She summarizes that “Crailo was a farm occupied by a succession of tenants until in 1704 it became a permanent home for the cadet branch of the Van Rensselaer family.”

1642: Not.

We now know the 1642 date on the marker to have been wildly untrue, with respect to the building that stands there today. Crailo was built in the early 18th century (probably 1704) by Hendrick Van Rensselaer, grandson of Kilian, the first patroon. (It may have then incorporated elements of a 1642 structure.)

The source of the 1642 date seems to be an inscription on a stone in the foundation that reads “K V R 1642 Anno Dominie,” along with another that contains a portion of the name of Domine Johannes Megapolensis, who lived in Greenbush from 1642 to 1649. But a stone with a date on it does not a house make, and Reynolds and most other researchers who aren’t reaching for antiquity recognize the rest of the building has nothing to do with 1642, and the stones were likely taken from another structure, a very common practice. Reynolds also asserts that it is very unlikely the current Crailo was built as a two story house, and that it more likely had a very steep pitched roof.

Reynolds theorizes that it was Hendrick Van Rensselaer, on being granted Greenen Bosch, who built a “large house in the style of the more pretentious houses in Albany,” with two full stories covered by a very steep roof. Hendrick lived there from 1704 until his death in 1740. Either he or his son, Johannes Van Rensselaer added a lower rear wing, where a brick marked “J V R” is set in the north wall, and another inscription reads “Rensselaer, 1762.” Reynolds indicates that could be the year the gambrel roof was added to the house.

The interior finish of the house was done over significantly by Johannes’s grandson, John Jeremias Van Rensselaer, around 1800.

Even if Crailo had been built in 1642, it would only have been among the oldest colonizer-built dwellings in the continental U.S.; several older dwellings still stand today.

Yankee Doodle

And of course, we can’t talk about Crailo without talking about “Yankee Doodle.” Here’s how Reynolds relates it:

“In general it must be said of Crailo that it has lost its original and typical architectural character and has become, like so many old homes, a register of social evolution. It was lived in by people of wealth, who occupied it with the greatest luxury of their period, and it was a center of social influence. So much has been written of the hospitality extended at Crailo to persons of prominent and importance that it would be gratuitous to touch again upon that side of its history. Also well known is the tradition that the lines of Yankee Doodle were composed here. That was in 1758. General Abercrombie, his staff and troops, on the way to Ticonderoga to battle with Montcalm, halted in the vicinity of Crailo. A young officer, it is said, was seated on the curb of the well near the house, saw the raw recruits coming on from the farms in motley garments and in his amusement at their appearance dashed off the famous doggerel.”

The song is more specifically credited to an army physician, Dr. Richard Schuckberg (or Shuckburgh). The version we know isn’t the version Schuckberg wrote, because that’s how America works. (Many accounts set a date of 1755, which doesn’t appear to make sense, as Abercrombie’s battle at what was then Fort Carillon was in 1758.)

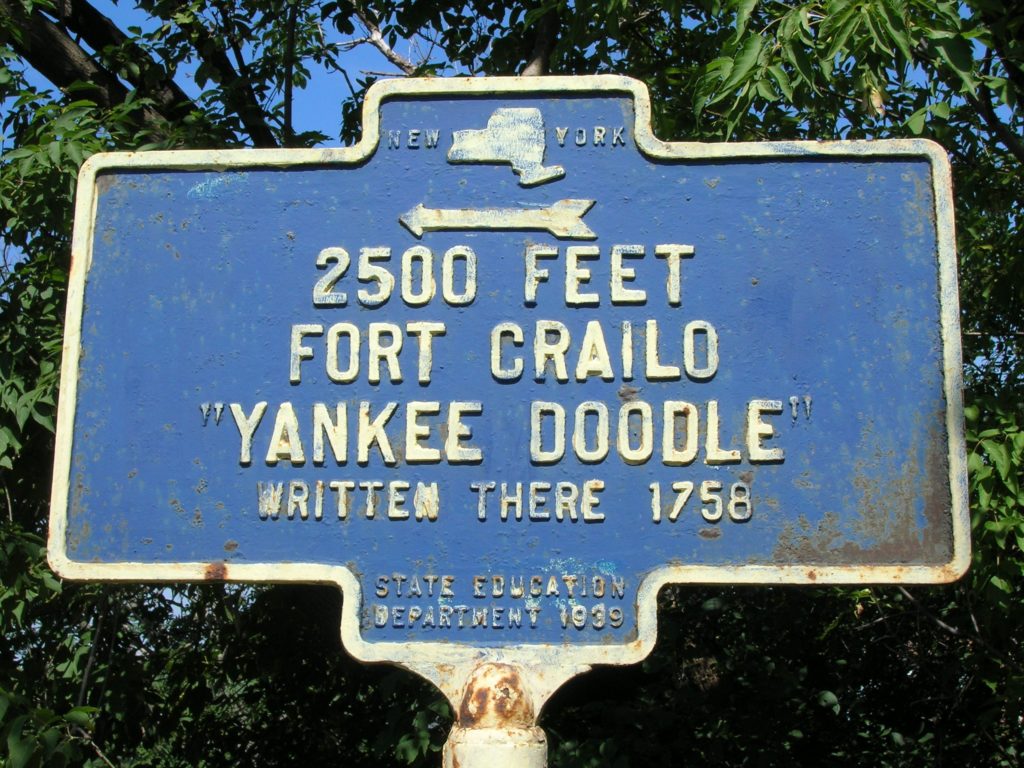

We lived next to Rensselaer for years, and yet don’t have a single photo of one of the several signs pointing to the home of Yankee Doodle. We rely here on Howard Ohlhous’s post to HMDB of this marker that was, at least in 2022 (according to Street View), still posted along the Columbia Turnpike at the bridge over the railroad tracks.

Decay and Rescue

Many articles and popular stories portrayed Crailo (then always called “Fort Crailo” – though the home had defensive features, it was never a fort) as the oldest house in America. This it never was. But even if it had been, that certainly didn’t cause much interest in preserving it. In 1910, the Christian Science Monitor wrote that,

“Silent and tenantless, the old house is yet impressive and dignified in appearance. The attic and an unornamental porch in front are comparatively modern. The interior is curiously planned, all the rooms on the same floor connecting with each other, usually by means of closets. There are several levels on the same story, the doors in some places opening several feet above the floor of the lower room. There were secret passages to the river and to the well, and there is still a trapdoor in the cellar ceiling.”

In about 1885, William Callendar of Greenbush had purchased the property for $14,000, $10,000 of which was in a mortgage held by Jane Van Schaick. An 1897 article reprinted from Leslie’s Weekly in the Portland, ME Daily Press said that since 1893 Crailo had been the property of the estate of Jane Van Schaick, “who died in Albany that year, soon after she had acquired title through mortgage foreclosure. The lack of a tenant resulted in negligence of the premises, and village vandals gained entrance by removing the boards from the windows, and they not only injured the fireplaces, but made way with the stairs and whatever they could move.” The New York Chapter of the Society of Colonial Dames held a fair trying to come up with the purchase price, but were unsuccessful. On August 4, 1897, Leslie’s reported, the property (which included two others houses and property) was sold in a “partition suit” to “John Circhenacher” for $4,300.

The New York Sun spelled his name as John Kurcenaker (there are several other spellings available), and said he beat out Albany lumber merchant George Welsh in an auction for the property that took place at Cole’s Tavern in New York City. He wanted the river frontage for his ice business. The Sun wrote:

“Whether the house will be refurnished and long remain to be respected by those who like to dwell on the historic past, or whether it will serve as an ice house, is a matter of conjecture by the many interested in old Fort Crailo, the oldest house in America.”

We repeat: not a fort, not the oldest house in America.

In Leslie’s Weekly of Jan. 19, 1899, Albany historian Cuyler Reynolds wrote about the 1897 sale of the estate to “an iceman of Rensselaer named Peter Kurcenaker,” noting that the value of Crailo itself was estimated about one-third of the property he had paid for, and that “the Yankee Doodle house” was out of repair principally “because relic-hunters had broken in and desecrated its parts.” It turned out that Kurcenaker couldn’t afford the repairs, “so he decided to tear it down and sell it brick by brick, believing that there was more money in it as a souvenir bank than as a house.”

Kurcenaker took out an advertisement to that effect, which brought angry responses at his proposal to tear down one of the oldest houses in the United States, some asking what it would cost to move it elsewhere. But it also brought bids on the materials, including from a Kentucky man who asked for 400 bricks so he could build a fireplace in his library, and from historical societies that asked for boards from which they would make cabinets, tables and bookcases. At the time of writing, it looked likely the house would be destroyed.

Finally, a Van Rensselaer stepped in. The Christian Science Monitor wrote:

“Many years ago the old house passed from the possession of the Van Rensselaers, and since 1893 it has been unoccupied. In 1897 it was sold at auction to an ice dealer. The probable destruction of the ancient landmark aroused the interest of several patriotic women, and in 1899 it was purchased, with a small strip of land, by Mrs. Ellen Van Rensselaer Strong of New Brunswick, N.J., representing a stock company, with the object of making the house habitable and eventually to make of it a historic museum, to be cared for by the Daughters of the American Revolution, to whom it would be presented. For several years, however, the matter has been at a standstill. The property is held by the little band of devoted women, who still hope to see their desires fulfilled. The roof is kept intact, and the solid walls might yet stand for centuries, but vandalism has stripped the interior of much of its ornamentation.”

A 1936 article in the Albany Evening News said that Crailo “suffered sadly from decay” for a century until the Daughters of the American Revolution “took up the task of preserving the historic shrine for posterity.” The News credited Susan De Lancey Van Rensselaer Strong (not “Ellen”) with the effort to have the DAR buy and restore the building, but nothing came of it in all those years. It wasn’t until 1924 that Crailo was gifted to the State of New York. Under the State’s care, restoration began in 1932.

“A year later, rebuilt as far as possible with original materials and with materials resembling as closely as possible the original, even to the addition which was built on the fort proper in 1740, the shrine was opened to the public.”

That didn’t prevent the Historic American Buildings Survey, in its 1940 notes, from calling the building’s present condition “Good, but recently completely renovated to the detriment of its authenticity.” After the vandals and the iceman, it’s not clear the renovations were to blame.

Originally held by the State Conservation Department, Crailo is now under the care of the State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, which says that “Crailo today tells the story of the early Dutch inhabitants of the upper Hudson Valley through exhibits highlighting archeological finds from the Albany Fort Orange excavations, special programs, and guided tours of the museum.”

Leave a Reply