Continuing our series on the tablet placed in honor of Albany’s charter bicentennial in 1886, we come to a marker that was intended to celebrate the Vanderheyden “palace.” Unfortunately, the tablet has been missing for more than 130 years – the building it commemorates has since been succeeded by three other buildings, and now it is just the open part of Ten Eyck Plaza.

Tablet No. 17 – Vanderheyden Palace.

Bronze tablet, 16×22 inches, inserted in front of wall of Perry building. Inscription:

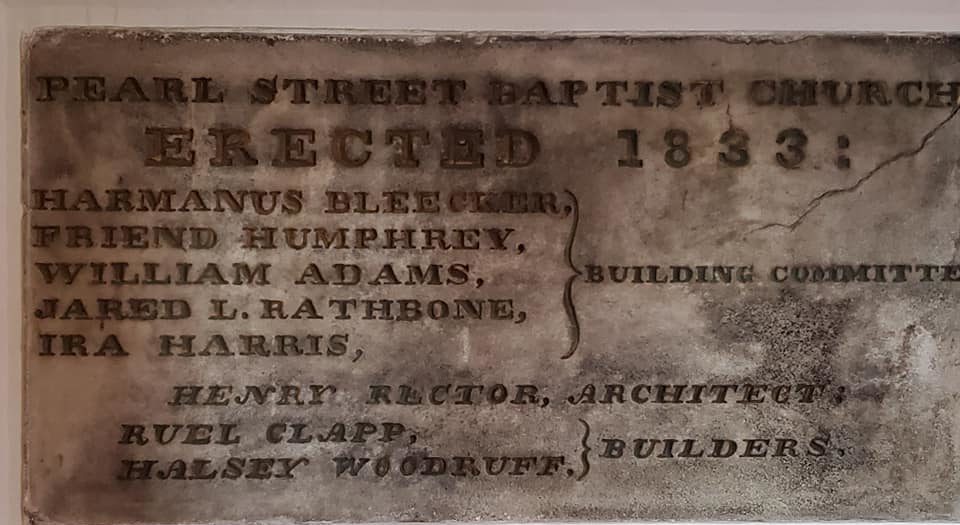

“Site of Vanderheyden Palace. Erected 1725. Demolished to make space for the First Baptist Church, 1833.”

Vanderheyden Palace

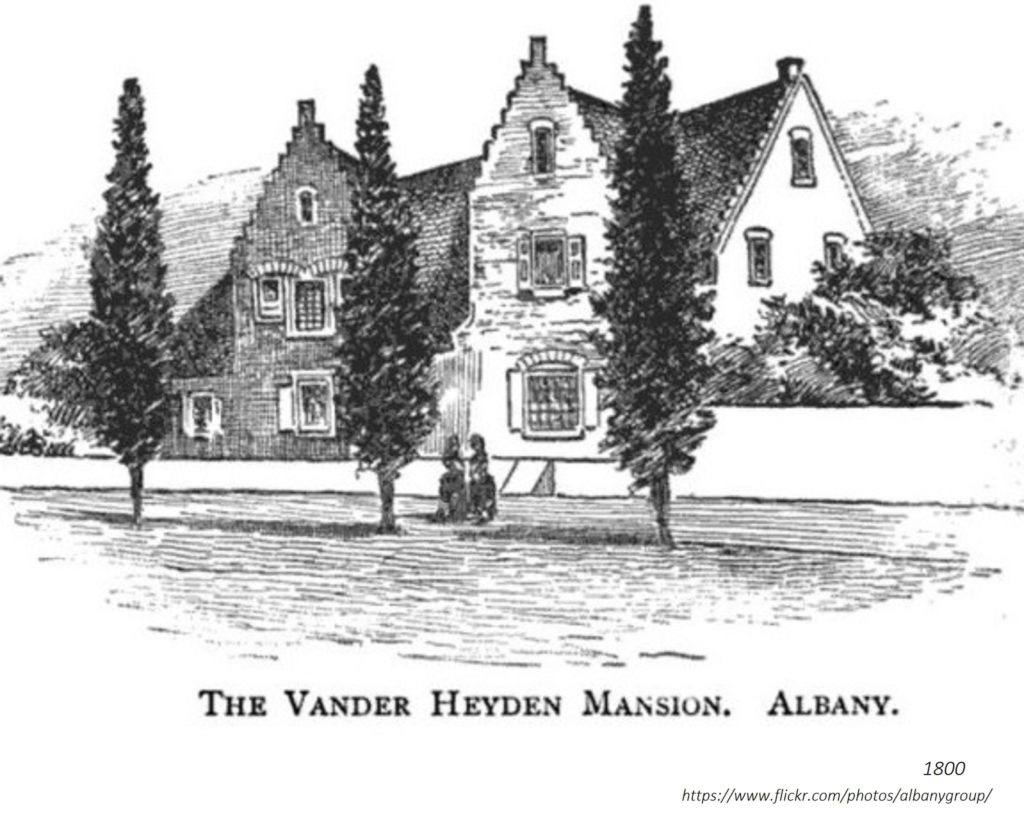

I had no knowledge of the Perry Building or Vanderheyden Palace before learning about this tablet. “Palace” may be overstating it, but the Vanderheyden mansion (yes, it can also be spelled Van der Heyden) was a stately structure dating to about 1725, originally built by Johannes Beekman. It stood at the southwest corner of North Pearl and Maiden Lane, when Maiden was still a through street.

Merchant Jacob Vanderheyden (part of the Vanderheyden family whose ferry landing established what became Troy) bought it in 1788, and it was as Vanderheyden’s residence that Washington Irving had occasion to describe the house in his novel “Bracebridge Hall.”

Jonathan Pearson, in his “A History of the Schenectady Patent in Dutch and English Times,” has a section on ancient Albany county buildings, and quotes Joel Munsell regarding the Vanderheyden palace. Munsell said it was built in 1725 and demolished in 1833. The original was 50×20 feet, having a hall and two rooms on each floor. “It is said to have been constructed of bricks, etc., brought from Holland.” Munsell questioned that, noting that by then there were brickmakers here, although bricks that served as ballast in ships were sometimes used in homes. In “Bracebridge Hall,” it was the home of Heer Anthony Vanderheyden. Munsell writes: “The iron weather vane, a running horse, was placed above the peaked turret of the door at Sunny Side,” Irving’s Hudson Valley home.

Pearl Street Baptist Church

In 1833 the “palace” was demolished to make space for the Pearl Street Baptist Church. We haven’t found much history of that church, grand though it was. It apparently was a congregation that separated from the First Baptist Church; an article in the Albany Morning Express in 1869 quoted the pastor, Dr. Bridgman, saying that the separation of 123 members was “with only sentiments of love for those from whom they separated,” seeking a more central and convenient location. Importantly, the bicentennial marker got the name of the church wrong.

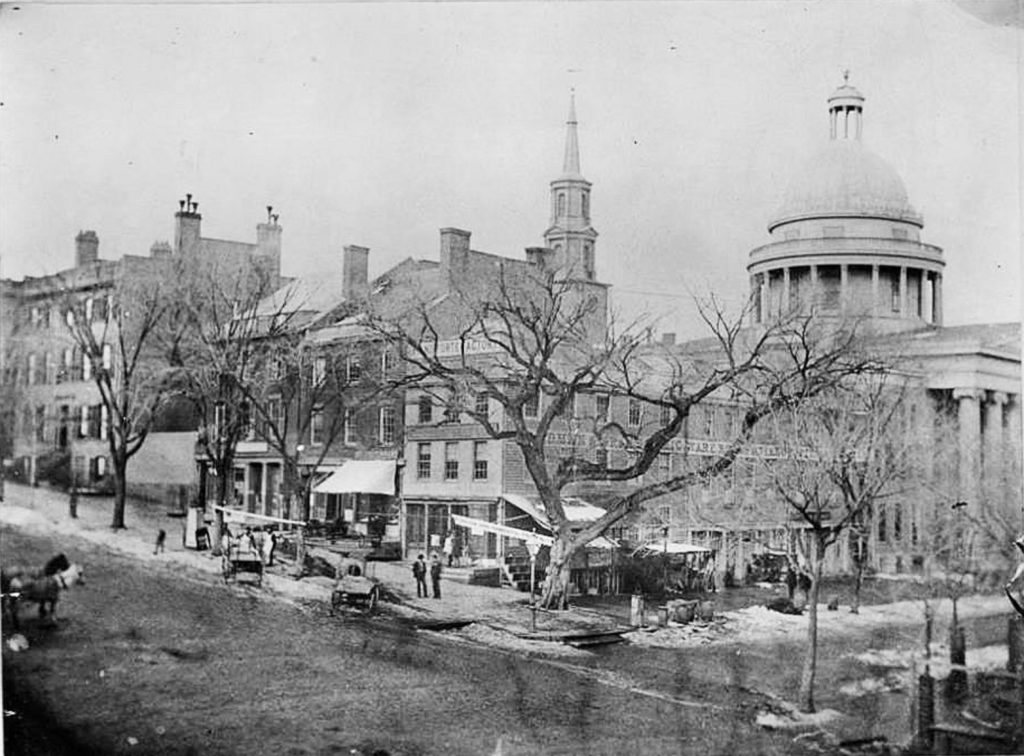

According to the history of the Emmanuel Baptist Church, by 1866 the Pearl Street church had been outgrown, and the congregation sought to build elsewhere, resulting in their current church building up on State Street between Swan and Dove.

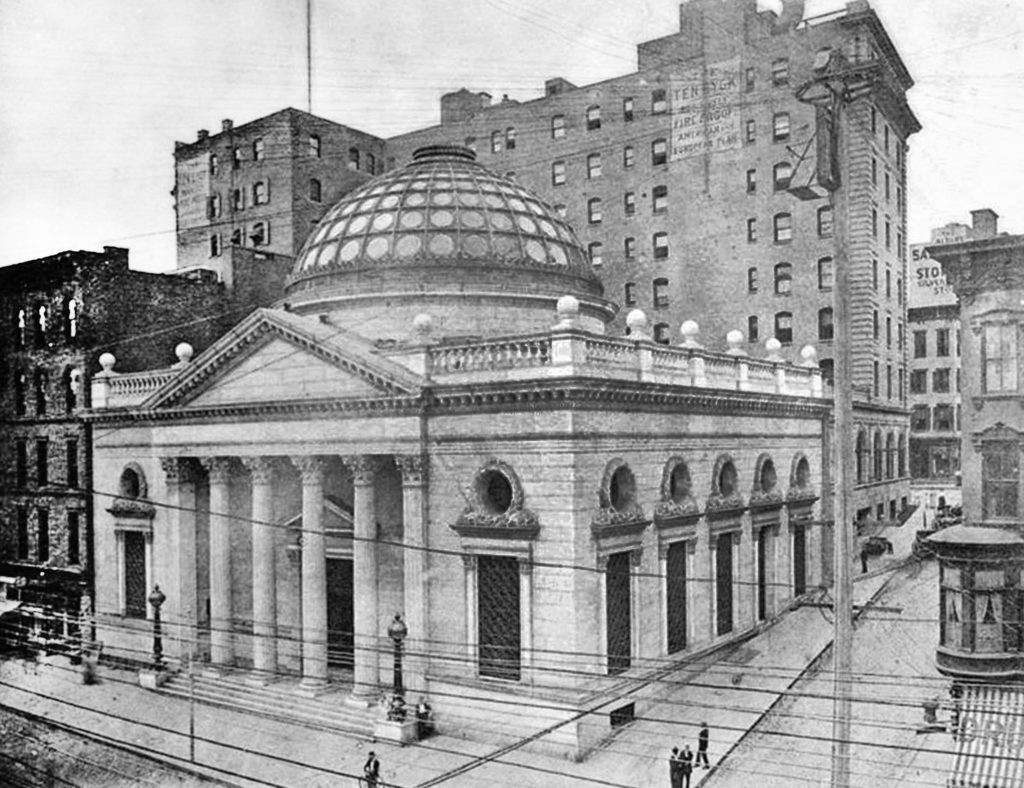

The Perry Building

One newspaper reported that in June 1870, the Pearl Street church was sold to the trustees of the Albany Savings Bank for $35,000 (estimated at $733,000 in 2021 dollars). But another report says it was sold to Eli Perry, a prominent member of the church who happened to live next door, owned a number of business and residential properties, and served several terms as mayor of Albany. He had the building substantially remodeled (certainly to the point of being unrecognizable on the outside), and christened it the Perry Building, which opened around 1871. A number of church congregations seem to have used it for their meetings at various times, and the Odd Fellows also occupied a large hall on an upper floor.

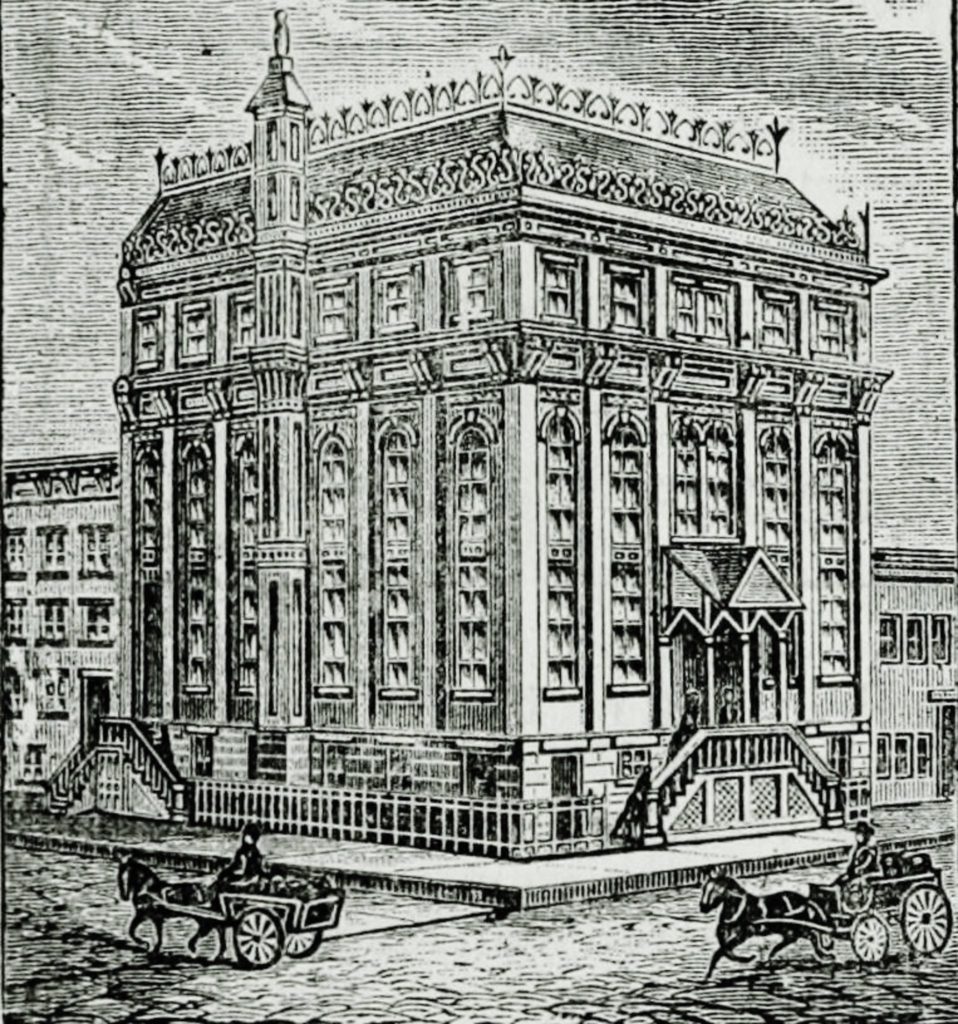

There was a fairly minor fire in the building in 1895, at which time the Argus called it “the old Perry Building,” despite it being barely 25 years since it had been substantially rebuilt. That article revealed that the top floor had previously been used as the Odd Fellows’ Hall; the third floor, where the fire began, was the art studio of Miss Charlotte Decker. “The second floor is occupied by Rummel Bros., decorators; Mr. Hirschberger, tailor shop; and Prof. Dennison, music teacher . . . The lower floor is occupied by Goldring Bros., florists. P.D.F. Goewey, jeweler, occupy the next door . . . The old Perry building was used as a church some twelve [sic] years ago by the Baptists of this city. The building was afterwards remodeled, and iron stringers placed in the granite front. The building is now owned by the P.J. McArdle estate.” In addition to the Baptists, it appears that the Unitarian Society also met there in the 1870s.

Albany Savings Bank: The marker goes missing

Perry died in 1881; 10 years after his death, his estate auctioned off all his property holdings, and the Perry Building was auctioned to Patrick J. McArdle, in 1891, for $47,800. In 1896, as the Albany Savings Bank acquired a series of parcels on which to build their grand new bank, McArdle was paid $66,000 for the property, and demolition began that summer. And here is where our bicentennial marker seems to have gotten lost. An 1898 article in the Albany Argus relates this story:

“‘I wonder what has become of the bicentennial bronze tablet which graced the old Perry building?’ asked a gentleman who stood in front of the new Albany Savings Bank on North Pearl street yesterday. ‘When the old building was torn down,’ he went on, ‘the tablet and the Odd Fellows’ sign that had been on it for years were removed. The Odd Fellows got one tablet and they took it away, but what became of the city’s bronze tablet I do not know.’ The Argus reporter, acting on the suggestion, called on Peter Kinnear. He made the bronze tablets, of which the city ordered a ton during its bicentennial year, 1886, and the gentleman who made the above remark was in the party of city officials which went about the city and placed the tablets on the historical buildings. Mr. Kinnear did not know what had become of the tablet, but he said that Wheeler B. Melius would know, for he always kept track of them. He was not at his office and could not be found last evening, for he is still living at his country home. It is just possible that the Albany Savings bank people intend to place this handsome tablet in a conspicuous place on its new building. Whether this is so or not was not learned yesterday, for J. Howard King could not be found. At the bank, however, nothing was known of the matter.”

Melius was a long-time municipal functionary who served in the county clerk’s office, along with many other positions, and was widely regarded as an expert in local real estate titles, a collector of maps, and the first person who tried to index the clerk’s records. He does seem like the guy who would have known. The Argus of October 9, 1898, wrote:

“Wheeler B. Melius has become to be looked upon as the custodian of the bicentennial historical tablets. Whenever an old structure containing one of these bronze pages of history is demolished, the tablet is either lost or mislaid or finds it way into a junk shop. When the Perry building was torn down for the Albany Savings bank building, the tablet on it disappeared, and has not since been discovered. This occurrence annoyed Mr. Melius, and he proposes to have a law enacted making it a misdemeanor for any one to sell or buy these tablets. Each one has cast on the back of it: ‘Property of the City of Albany.’”

It doesn’t seem like ol’ Wheeler ever turned this one up. A much later article on missing tablets in the Argus in 1914 indicated that “this site is now occupied by the Albany Savings bank, and no one connected with the bank knows anything about the tablet.”

Albany Savings Bank was formed way back in 1820. Was there also an Albany City Savings Bank, owned by the Cornings? Yes, there was. Did that cause confusion? Yes, it did. Albany City Savings Bank later became the City Savings Bank of Albany, allaying almost no confusion. There was also an Albany County Savings Bank, also a different institution. Eventually City Savings Bank and Albany County Savings Bank merged into City and County Savings Bank.

Meanwhile, plain old Albany Savings Bank just kept on going about its business. It was still operating in its grand building in 1968, when the closure of the Ten Eyck Hotel and subsequent departures of businesses there started people thinking about “renewal.” In 1970, the State’s Urban Development Corporation bought the Ten Eyck Hotel and entered negotiations with the bank to buy its parcel, in order to build a four-block complex including a new hotel, a bank, retail stores, an office tower, and underground parking for 1300 vehicles. A surprising amount of that plan actually happened, except of course the parking. In fact, the bank did move into the new complex, and its old tablet is visible inside the current bank building, by the elevator.

Long after Albany Savings had left its Maiden Lane location and taken on the horrific “Albank” moniker, they were merged into something called Charter One Bank of Cleveland in 1998, which was merged into something called RBS Citizens of Providence in 2007, a collection of banks operating as Citizens Bank, which it seems to be still.

Leave a Reply