Once upon a time, the construction of a new office building really meant something – it was a point of pride for a community to know that a modern structure with all the modern amenities was being constructed to serve the premiere business of the city. The Lorraine Block was just such a building.

In 1899, Welton Stanford, hardware store and real estate magnate bought up property at the corner of State and White streets (White later became Clinton) and began to have plans drawn up for his “dream block.” Welton was the son of State Senator Charles Stanford, and nephew of Leland Stanford, and was the last Stanford to live in the Locust Grove homestead that later became the Ingersoll Memorial Home for Aged Men, and still stands (sorta). In building his modern office block, Welton named it for his only daughter, Lorraine, who was 14 when the building was completed in 1902. (Much more on Welton below.)

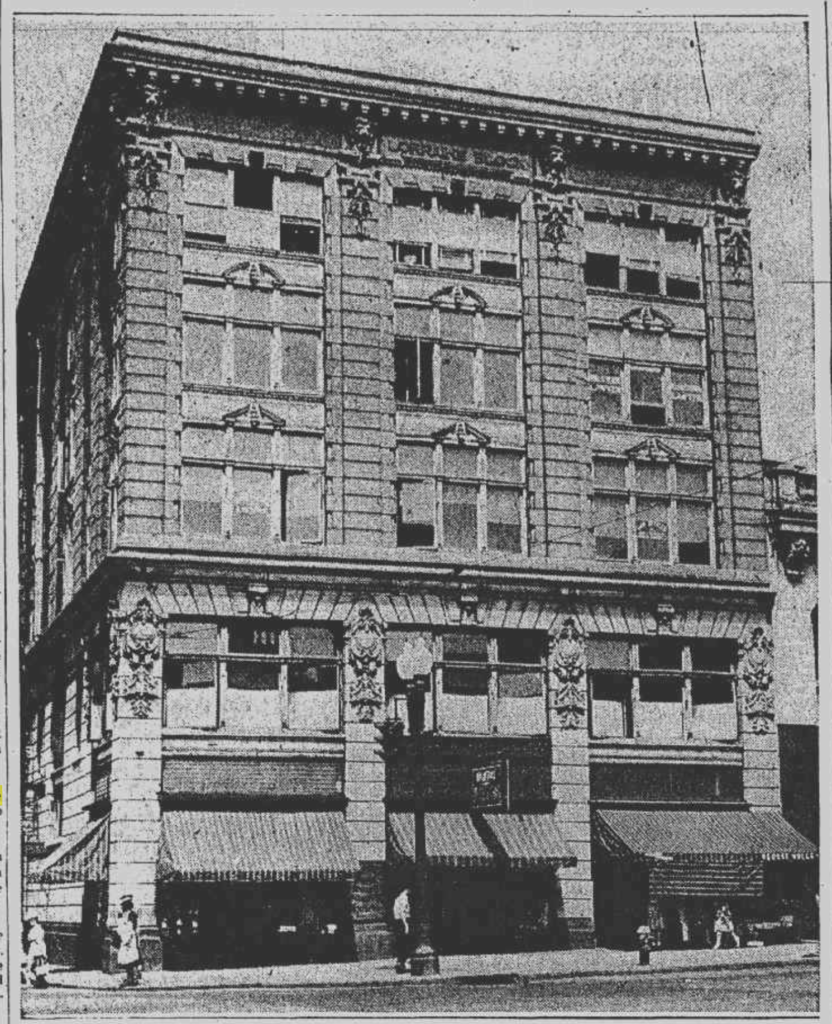

Stanford was running a real estate office at 145 Jay Street as well as Stanford Hardware, in the Stanford Block on the northwest corner of Broadway (Center Street) and State. That building later became part of The Imperial store, and is now Mexican Radio. The Schenectady Daily Union was established there in 1865 by Charles Stanford. Much of this information comes from an article by the legendary Larry Hart from 1972, who wrote: “When tenants began moving into its gleaming office space early in 1902, the five-story Lorraine Block had officially joined the ranks of the more impressive structures in downtown Schenectady. It was looked upon as a symbol of the city’s reawakening to an industrial and economic boom to begin the new century.” For many years, it was considered Schenectady’s premiere business location.

What came before

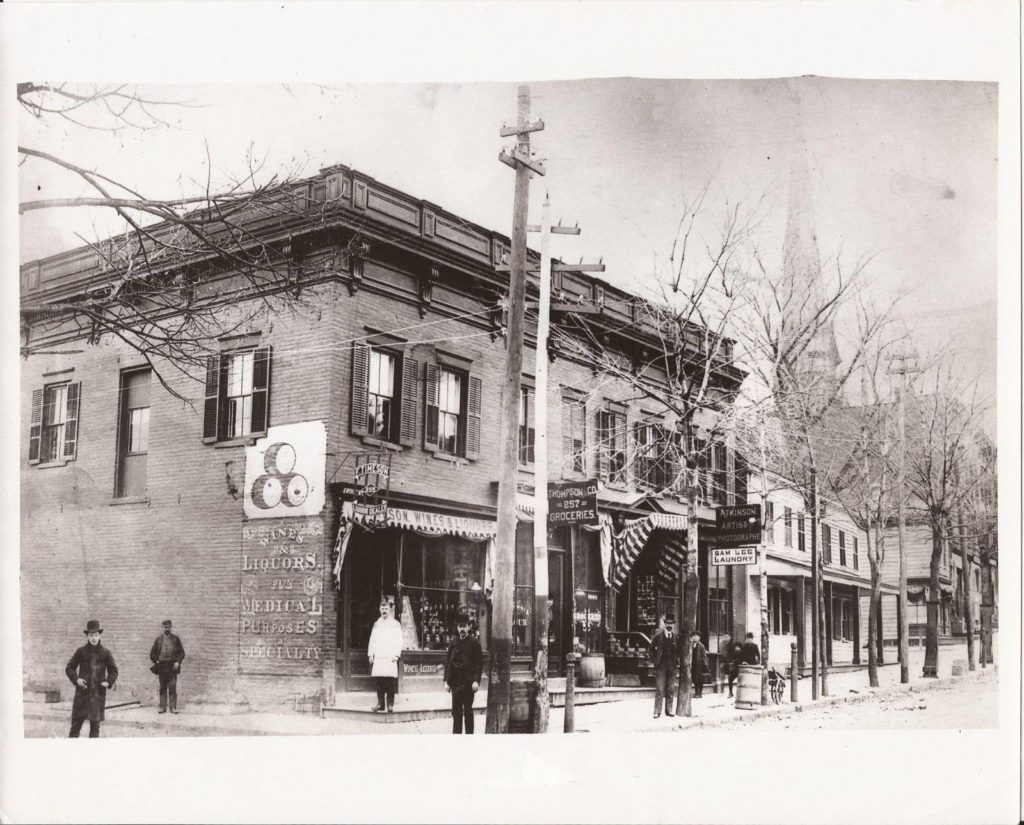

Before the construction of the Lorraine Block, the site held a two-story brick building that housed several businesses, including Hebner & Sleeter’s grocery store, Sam Lee’s Chinese laundry, and apartments. Next to it (visible on the right in the photos above and below) was a story and a half wooden landmark known as Park House and, later, Wasson’s Park House or Wasson’s Hotel. That building gave way to a new headquarters for the Schenectady Illuminating Company – in later years it housed Walker’s Pharmacy.

There was a complication in its construction – the old Cowhorn Creek (also Coehoorn Kill) ran right through the property. The creek ran from a mile east of Schenectady, flowed down through McClellan Street and through the cemetery, over Liberty Street and through Clinton, across State to Dakota street, and then out to the river. Hart reported that Stanford was able to use his influence to get the creek diverted from his property, although it continued to be a problem for the surrounding area until the WPA diverted the Cowhorn into underground sewer pipes in 1941.

Larry Hart wrote, “Once it was built, the Lorraine Block became Welton Stanford’s business quarters. His was the first office to be opened. To the rear, Olney Redmond opened the first of his restaurants in Schenectady. . . In 1923, three floors were added to the rear portion of the Lorraine Block, in fact over that portion which had once housed Redmond’s Restaurant. The building itself extended 102 feet along Clinton Street, with 53 feet of frontage on State Street. For many years, it was the only structure in the downtown area with two passenger elevators.

“There have been a lot of tenants in the Lorraine Block and rarely was it not filled to capacity. Its office space was a favorite of attorneys, especially, over the years. The ground floor business accommodations enjoyed some long-time occupants. One of these, located at the corner of Clinton and State during the 1930s and early 1940s was the Farm Restaurant.”

Sales and resales of a landmark

That 1923 addition came about as the result of a sale to a real estate man named Peter Arthur, following the death of Welton Stanford in 1922. Welton died in Los Angeles (presumably visiting daughter Lorraine), and his body was brought home to Locust Grove and then buried at the Stanford Mausoleum in Vale Cemetery.

In 1944, another sale of the Lorraine Block at 505 State Street made news as the “largest transaction of its kind in Schenectady in many years.” Held at the time by Schenectady Savings Bank, which had taken the building in a foreclosure against the Lorraine Office Building, Inc. in 1940, it was to be sold to a new corporation made up of unnamed “local persons,” one of which seems to have been the attorney Alexander Diamond. He was joined at least by Nathan Bilgore, a liquor distributor, and real estate broker William Friedman. The property was then assessed at $177,000, $95,810 on the land and $81,190 on the building, the largest assessed property of its kind in the city. It was also said to be the only structure of its kind with two elevators, installed in the 1923 expansion. Its five stories contained stores on the ground flood and offices on the upper floors. First floor tenants included Save Supply Co., Walker’s Pharmacy, American Fruit Co., Lorraine Barber Shop and Perfection Shoe Shop. Ten years later, the Lorraine Block was sold again, for $250,000, to “members of a nationwide real estate syndicate” based in Brooklyn. It was still noted as the only building downtown with two passenger elevators, and it was still perhaps the highest assessed building of its type. At the time of the 1954 sale, tenants included Walker’s Pharmacy, the Lorraine Barber Shop, Debs Clothing Shop, Perfection Shoe Repair, dentists and a podiatrist, and lawyers and insurance and real estate brokers. The building changed hands again in 1963. (Interesting to note that in reporting the 1954 sale, the Gazette used exactly the same photo of the building it had used in 1944.

The end

The building went into bankruptcy in 1971 and came to an end in 1972, when the Albany Savings Bank bought the Lorraine Block, the former Illuminating Company building, and the site of the former Strand Theater to build a branch office. By then, the Lorraine had fallen into the state of shabbiness that prevailed in downtown Schenectady at the time, and it must have seemed that any sort of modern building and new business was a welcome improvement. But, wow, what a piece of 1972 junk they built there – a faceless, brick-clad wedge in place of two of the more lovely buildings ever to grace the street. A Gazette editorial lamenting the loss of the Lorraine foresaw what was going to happen “as many old structures are either biting the dust or getting a face-lifting.” They said that “Whatever is done, whether it’s a whole block or several blocks of alteration, we can only hope that it is done according to a rigid plan calling for good taste and architectural compatibility. If an overall scheme is abandoned and developers are free to effect changes haphazardly, Schenectady’s main stem might resemble a circus midway.”

Lorraine

Whatever became of Lorraine? Only 14 when her namesake building was opened in 1901, she was married in 1910 to Glen Huntsberger (a graduate of Stanford University) and moved to Los Angeles, California. In 1972, Larry Hart inquired whether she had any memories of her namesake building, and she noted that “perhaps the one which remains most vivid was of Walker’s Drug Store where they sold the most delicious ice cream sodas for only 10 cents.” Lorraine shows up in the social columns from time to time as she returned to Locust Grove to visit her mother. Beyond that, though, we haven’t learned much about Lorraine herself.

An appreciation of Welton Stanford

All of this may lead one to think that Welton Stanford was a lifelong Schenectadian – but apparently not. A brief biography in the “History of Los Angeles County, Vol. 2” indicates that he was born in Albany to Charles and Jane Stanford. When Charles was induced to go west by his brother Leland (who ran a railroad or started a university or something), Welton was moved west as well.

“Mr. Stanford was for many years identified with California interests. He spent his early youth in this state. His father, Charles Stanford, came to California in 1849 and started a business in Sacramento, during the early gold rush, while later he became actively associated with the business activities of his brothers Josiah and Leland Stanford. Welton Stanford again came to California at the time of the opening of transcontinental railroad service, and was connected with the railroad offices in Sacramento. He came from Australia, where he had spent about two years in business with an uncle at Melbourne. He eventually returned to Schenectady, New York, where he long maintained his home, his residence having been formerly owned by General Schuyler, of Revolutionary fame, and having been continuously occupied by the Stanford family for five generations.”

When he returned to Schenectady, he became editor and publisher of the Daily Union, the newspaper that father Charles had started. Retiring from that, he went into real estate (his family, after all, held vast tracts of land). “He took lively interest in civic affairs, was a member of leading social clubs, and was an earnest member of the Dutch Reformed Church, as is also his widow, who now resides in Los Angeles. For fifteen years Mr. Stanford conducted a little Methodist Chapel, which he later presented to the parish and which is now known as the Stanford Methodist Community Church at Schenectady. He served for many years as elder of the Dutch Reformed Church at Lishaskill, the Schenectady suburb in which he resided, this having been the birthplace of his wife, whose maiden name was Katharine G. Lansing, and who is a representative of a family whose name has been one of prominent in American history for many generations, dating back to Colonial times. The marriage of Mr. and Mrs. Stanford was solemnized September 27, 1876, and nearly half a century passed ere the gracious bonds were severed by the death of the revered husband and father. Mr. and Mrs. Stanford became the parents of three sons and one daughter: Welton, Jr., is a resident of Detroit, Michigan; Charles died at the age of ten weeks; Grant Lansing is a representative member of the bar of Schenectady, New York; and Lorraine is the wife of Glen E. Huntsberger, of Los Angeles. In the home of Mr. and Mrs. Huntsberger, at 16 South Kingsley Drive, the widowed mother now resides.”

That all came from an appreciation in a Los Angeles paper shortly after his death from stroke at the Huntsberger home on Jan. 14, 1922.

Leave a Reply to Carl Johnson Cancel reply