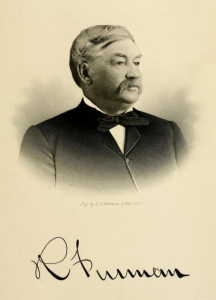

Some of the details of how the Edison Machine Works (now you know it as General Electric – GE) came to be located in Schenectady are lost to time, but it’s very clear that it wouldn’t have happened had it not been for the efforts of Col. Robert Furman, once a real mover and shaker and now a name barely noted in the city. Furman was originally from Franklin in Oneida County. He moved at 17 to join his brother Rensselaer Furman in Schenectady, clerking in Rensselaer’s store. He then went to work for the merchant Myndert Van Guysling and took the time-honored path of marrying the boss’s daughter. Furman seems to have had a talent for organization and entrepreneurship, and was an endless booster of local business and civic concerns. He was apparently close to Governor Horatio Seymour and was asked to raise a militia regiment, the 83rd infantry, during the Civil War, thus becoming a colonel, but he never saw battle. He was elected to the state Assembly for a term, and directed significant appropriations to Schenectady, including for the first armory along Crescent Park, which he also had a hand in creating. He helped create the local YMCA, and advocated for a street railroad. He dabbled in railroads as well. The building he constructed at the northeast corner of State and Ferry, long known as the Furman Block, still stands today (apparently part of Schenectady County Community College – to people my age, it was Roberts Piano Store). His home at Smith and Lafayette still stands, as St. Joseph’s Rectory. There was much more. But he was perhaps most important, and most instrumental in the effort to bring Thomas Edison’s works to Schenectady.

Some of the details of how the Edison Machine Works (now you know it as General Electric – GE) came to be located in Schenectady are lost to time, but it’s very clear that it wouldn’t have happened had it not been for the efforts of Col. Robert Furman, once a real mover and shaker and now a name barely noted in the city. Furman was originally from Franklin in Oneida County. He moved at 17 to join his brother Rensselaer Furman in Schenectady, clerking in Rensselaer’s store. He then went to work for the merchant Myndert Van Guysling and took the time-honored path of marrying the boss’s daughter. Furman seems to have had a talent for organization and entrepreneurship, and was an endless booster of local business and civic concerns. He was apparently close to Governor Horatio Seymour and was asked to raise a militia regiment, the 83rd infantry, during the Civil War, thus becoming a colonel, but he never saw battle. He was elected to the state Assembly for a term, and directed significant appropriations to Schenectady, including for the first armory along Crescent Park, which he also had a hand in creating. He helped create the local YMCA, and advocated for a street railroad. He dabbled in railroads as well. The building he constructed at the northeast corner of State and Ferry, long known as the Furman Block, still stands today (apparently part of Schenectady County Community College – to people my age, it was Roberts Piano Store). His home at Smith and Lafayette still stands, as St. Joseph’s Rectory. There was much more. But he was perhaps most important, and most instrumental in the effort to bring Thomas Edison’s works to Schenectady.

In 1886, the Edison Machine Works, building the Edison tubes that carried power underground, was located on Goerck Street in lower Manhattan. That was a cramped works, sometimes running lathes out on the sidewalks, with no opportunity to expand, and so Edison was on the search for a new factory site.

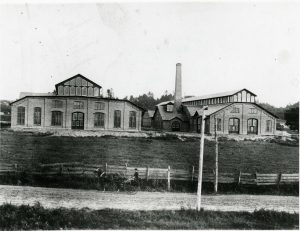

It happened there were two unfinished factory buildings on the outskirts of Schenectady (the plant was in Rotterdam until it was annexed into the city), intended to be the McQueen Locomotive works, a company formed by Walter McQueen, who was breaking off from the Schenectady Locomotive Works (later ALCO) and State Senator Charles Stanford. Stanford put $72,000 into the buildings, but according to the Schenectady Daily Union, “McQueen resigned before any machinery was in place and Senator Stanford died unexpectedly so that the project was stranded.” With McQueen gone back to the old locomotive works and Stanford dead, Stanford’s estate was left holding two buildings without a purpose, and looking at a significant loss. That might have been that, had it not been for Col. Furman, who was determined to secure an industrial future for the site and the city, where the locomotive works was the only major industry.

How Edison’s scout Harry Livor became aware of the Schenectady site depends on which version you care to believe. A Schenectady Gazette story from 1936 said that Livor dispatched to scout upstate, “observed the two gaunt, unfinished buildings from the window of his train, and forthwith stopped off at Schenectady to investigate. As soon as he had the facts in his possession, he notified Edison, who sent his financial agent, Samuel Insull, to look at the site.”

That’s one version. The other, less repeated, is that Livor was stopping at the Delavan House in Albany, negotiating for a site on a river island in Albany. Which island, we are not told, and there is no mention of such a visit or other possibility of Edison’s works coming to Albany that we can find. But in this version, Robert Furman hears that Edison’s scouts are at the Delavan and hastens to Albany to convince them to come to view the unfinished McQueen works.

The Daily Union wrote that:

“Chief [Detective] Ben Van Dusen distinctly recalls the events of the time and says that ‘the Edison people were in Albany stopping at the old Delavan House. They were negotiating for an island in the river there. Col. Furman heard of it and went there as fast as he could get there. He saw these men at the Delavan House and told them that here in Schenectady were two buildings already built and ready for occupancy: well located and suitable for their use. He not only persuaded them to see these buildings but at once secured barouches from Matt DeFreest’s livery stable and brought the crowd over here as quickly as practicable.”

Either way, it’s clear that Furman was instrumental. The debtholders of the McQueen works, apparently the Stanford estate, wanted $45,000 for the property (eight acres in all), but Edison was only willing to pay $37,500. Neither side would budge. Col. Furman started banging the drum or passing the hat or however you want to phrase it: the citizens of Schenectady contributed the $7,500 difference.

Raising that sum of money was not a foregone conclusion for what was then a pretty sleepy little community, with the single major industry of locomotive building and a broom industry in decline. Edward F. Cohen, who then worked for grocer Jonathan Levi, recalled the effort in a story in 1928, telling that N.I. Schermerhorn, Charles Thompson, Sam W. Jackson, “Bob” Furman and another gentleman (perhaps H.S. Barney) came to see Mr. Levi, saying that they had all but the last $500. They said the Edison works would employ 200 by Oct. 1st of that year, 400 by January 1st of the next year, 1,000 within three years, “and in time probably 2,000.” That was one of the few underestimations in business history. Levi promised half the last $500, and with another key contribution from an anonymous citizen, the last of the $7,500 was raised by the end of June, 1886.

By December 1, the factory was starting to operate. 25 men were working; within a few weeks, 300 workers moved up from New York. The Edison Machine Works was on its way.

In his “Schenectady County: Its History,” Austin Yates, who had lost an election to Furman, wrote:

“In person Colonel Furman was a man of full habit, portly and well preserved. There was nothing of the keen and wily look that romance gives to the successful capitalist. His manner and speech were open, frank and blunt and permeated with a sense of humor that was almost joviality. He was unstintingly charitable to the poor, intensely sympathetic with the suffering, yet so unostentatious that few knew from whence came the sorely needed help. Merchants were directed to send abundant stores and from his own doors almost daily went relief to every worthy soul of whose trouble he knew.” Furman died on January 5, 1894, at the age of 68.

Leave a Reply