Continuing with our series on the bicentennial tablets placed around the city of Albany in honor of the bicentennial of its charter – but we don’t have a lot to say about a long-missing plaque for a long-gone watercourse.

Bronze tablet, 16 x 22 inches, in southern wall of building north-west corner of Canal and North Pearl streets. Inscription: “Foxen Kill — Ancient Water Course flowing in Early Times to the River — Now Arched over. This is Canal, Formerly Fox Street.”

In 1914, the Albany Argus listed it among three tablets that had been refastened with slot-headed screws, “instead of having the heads filed flat as originally;” more than that, they noted that the screws on this one had loosened. In 1876, the building on that corner was owned by E. Vischer, and around the time the plaque was placed, it was home to White Sewing Machines and apartments or a rooming house. That building is long gone, and there is no sign of the tablet.

Janny Venema, in her tremendous resource “Beverwijck: A Dutch Village on the American Frontier, 1652-1664,” writes about the “third kill,” which marked the northern boundary of the village. She writes that it was called the Vossenkill (Fox Kill), “probably because Andries de Vos had his residence on it.” After 1653, a brickyard and tile kiln was established just north of the third kill, and Broadway was still close enough to the river that the kiln was damaged by an ice floe in 1666 (as were several other houses and barns, up and down the street).

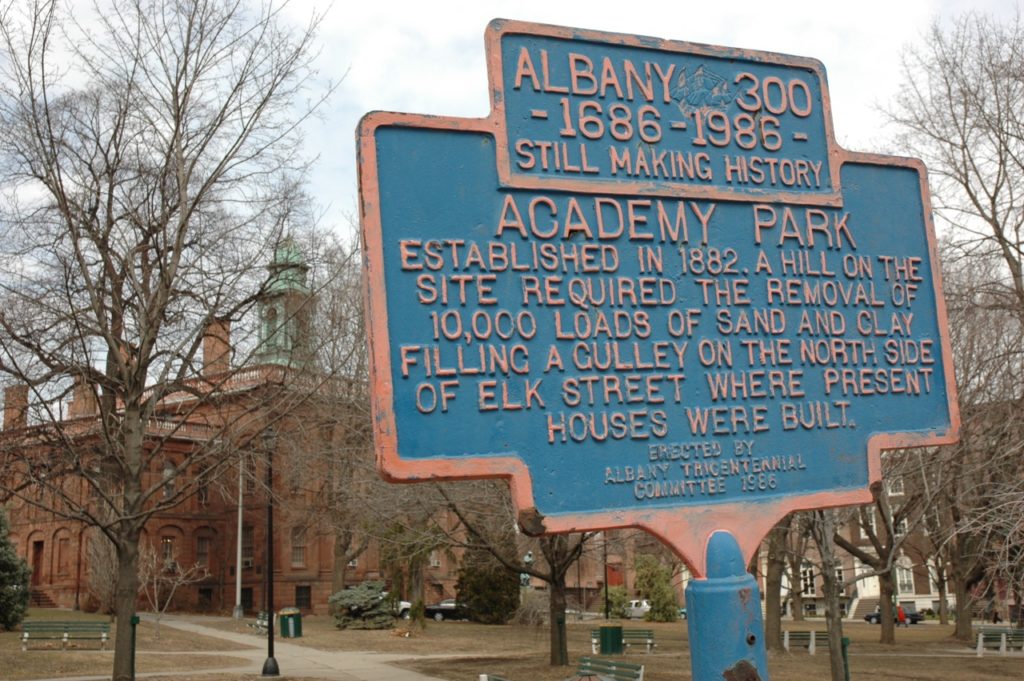

The Foxen Kill began somewhere up the hill along or near modern Washington Avenue or Elk Street, and flowed down the hill and then through a ravine down that cut through modern-day Academy Park (which was substantially filled in), along Eagle Street and into what is now Sheridan Avenue, then emptied into the Hudson River at the foot of Columbia Street (when the Hudson shoreline was much further west than it is today). The ravine is evident on the 1698 Roemer map, just beneath the legend cartouche:

Earliest Albany was marked by three major kills, the southernmost being the Beaver Kill, or first kill; the second being the Rutten Kill; and the third being the Vossen Kill.

An 1859 article attributed to Joel Munsell said that “The Foxen kill, when the city was first settled, and for a long time after, afforded an abundance of fish. It ran outside of the stockades, which for a great many years formed the northern boundary of the city. It is but little more than a quarter of a century [prior to 1859] since it was crossed by a bridge in North Pearl street, near Orange.” By 1859, all three had been converted into sewers, redirecting rainwater and worse down to the river, covered over or channelized. The street that ran alongside, and perhaps over, the former Foxen Kill became known as Fox Street, naturally enough. At some point it became Canal Street, and was so named in 1849’s “Annals of Albany,” where Munsell wrote that it ran from North Pearl to Snipe Street (now Lexington). Eventually Canal extended another block west to Robin Street.

The Albany Times and Courier, in complaining about the nuisance of the Albany Basin in 1865 (complaining about the Albany Basin was a major pastime in the 19th century), recalled that in 1832 a cholera outbreak had begin on July 3 “at the rendezvous for the army recruits, at the foot of Columbia street, and likewise at the foot of Maiden lane; from these locations it spread itself in either way, until it reached the public sewers of the old ‘Foxen kill’ and that of Hudson street; from thence it proceeded in a fatal manner up the courses of these streams to the surface of the ‘Pine Plains.’” The Albany Basin was blamed. It’s entirely likely it was the kills that carried cholera, given they were treated as sewers, and more likely they were contaminating the basin than vice versa. Nevertheless, it was this outbreak that drove the effort to convert the Foxen Kill into an actual sewer.

Local columnist Edgar Van Olinda, writing in 1965 for the Times-Union, said that:

“Branching from the old bed of the ‘Foxen Kill,’ was a deep ravine, passing under the land where the Cathedral of All Saints now stands. Further on, the water ran under what is now the Education Building . . . It is thought that this ravine extended to the parade grounds of Fort Frederick, which stood at the top of what is now Capitol Hill with its northeast bastion on the site of the present St. Peter’s Episcopal Church.”

He went on to indicate that considerable quicksand conditions were encountered when setting the foundations of the Education Building and, later the Alfred E. Smith State Office Building, conditions caused by the previous watercourses. It’s also worth noting that the area that is now Academy Park was substantially filled in at some point, so the course of the water was likely down to what is now Sheridan around Eagle Street. The old 1698 Roemer map confirms this, showing a deep ravine plunging down to the Foxen Kill, with perhaps another stream leading into it below.

Not too surprisingly, the street was originally named Fox Street; when it was changed to Canal is not clear, nor is the genesis of that name. It was Canal, running from North Pearl to Snipe, in 1849’s “Annals of Albany.” Munsell in that edition writes of an 1848 drowning that occurred in the pond at the head of Canal street, “formed by the pent up waters which formerly supplied the Foxen Kill. This was the sixth life lost in the pond during two years.”

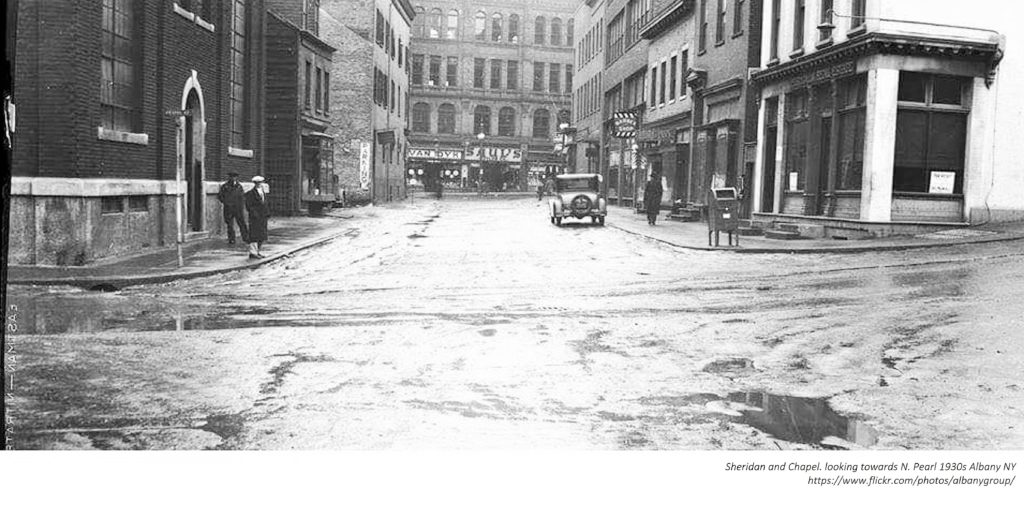

According to Van Olinda, in 1900 Canal Street was renamed Sheridan Avenue in honor of General Philip Sheridan, the West Point graduate from the class of 1853 who became a key Union general, who also pursued a scorched earth policy in the Civil War and later was responsible for all kinds of horrors perpetrated against Native Americans. There has always been a bit of controversy about Sheridan’s Albany bona fides. Van Olinda wrote that as a child, Sheridan lived on Canal Street, “diagonally across the street from the present publishing offices of Capital Newspapers,” meaning what is now a parking lot (naturally) at the northeast corner of Chapel and Sheridan. Some have suggested that Sheridan’s family made only a brief stop in Albany as they moved west, and his birth in Albany (which some dispute, and Sheridan offered conflicting evidence) in 1831 had no particular meaning as his family never lived there. . In his memoirs, Sheridan indicates that his parents came from Ireland to Albany at the suggestion of his uncle, and intended to remain there, but they weren’t able to succeed in Albany and in 1832 moved to Ohio. However, some say he lied about being born in Albany because he had political ambitions and needed to claim native birth, when he may actually have been born on the passage from Ireland.

In 1951 a plan was announced to widen Sheridan between Chapel and North Pearl, from 20 feet to 43 feet, which meant the building on which the bicentennial plaque had been placed, 92-96 N. Pearl Street, would have to be demolished, along with buildings at 9, 15 and 23 Sheridan Avenue. “The single block of Sheridan between N. Pearl and Chapel is currently a fire lane because of its narrow width,” the Knickerbocker News reported, adding – as if this were not a foregone conclusion – “The widened portion would be repaved.” The three-story brick building at 92-96 N. Pearl then included George Dolmas’s restaurant and grill, and Menchel’s Fur Shop, with eight apartments above. The former United Traction Company powerhouse at 15 Sheridan had recently been demolished by the owner.

The demolition didn’t happen right away, however; as late as 1960, the building was still there, hosting Peek’s Cleaners, George Dolmas’s restaurant and Menchel’s Furs. Menchel’s moved to 56 North Pearl in September 1961. In May 1961, it was announced that planning had started for the “long-awaited widening and resurfacing of lower Sheridan Ave.” Apparently a dispute with the owner of 92-96 N. Pearl, Coplin Yaras, blocked the project for a decade; in the end he was awarded $98,000. By then the only tenants were George’s Restaurant, Menchel’s Furs “and a widow who lives in an upstairs apartment.”

In none of the articles is the bicentennial marker mentioned.

Leave a Reply