Continuing our series on the tablets placed in honor of the bicentennial of Albany’s charter as a city, tablet number 14 marks the location of “the old Lansing house,” or Pemberton Corner.

Tablet No. 14 — The Old Lansing House

Bronze tablet, 11×23, inserted in a granite block, similar to No. 7, in walk in front of the present house at Pearl and Columbia streets. Inscription:

“Built 1710—Known for 68 years as the Pemberton Corner—a Trading House outside of the Stockade.”

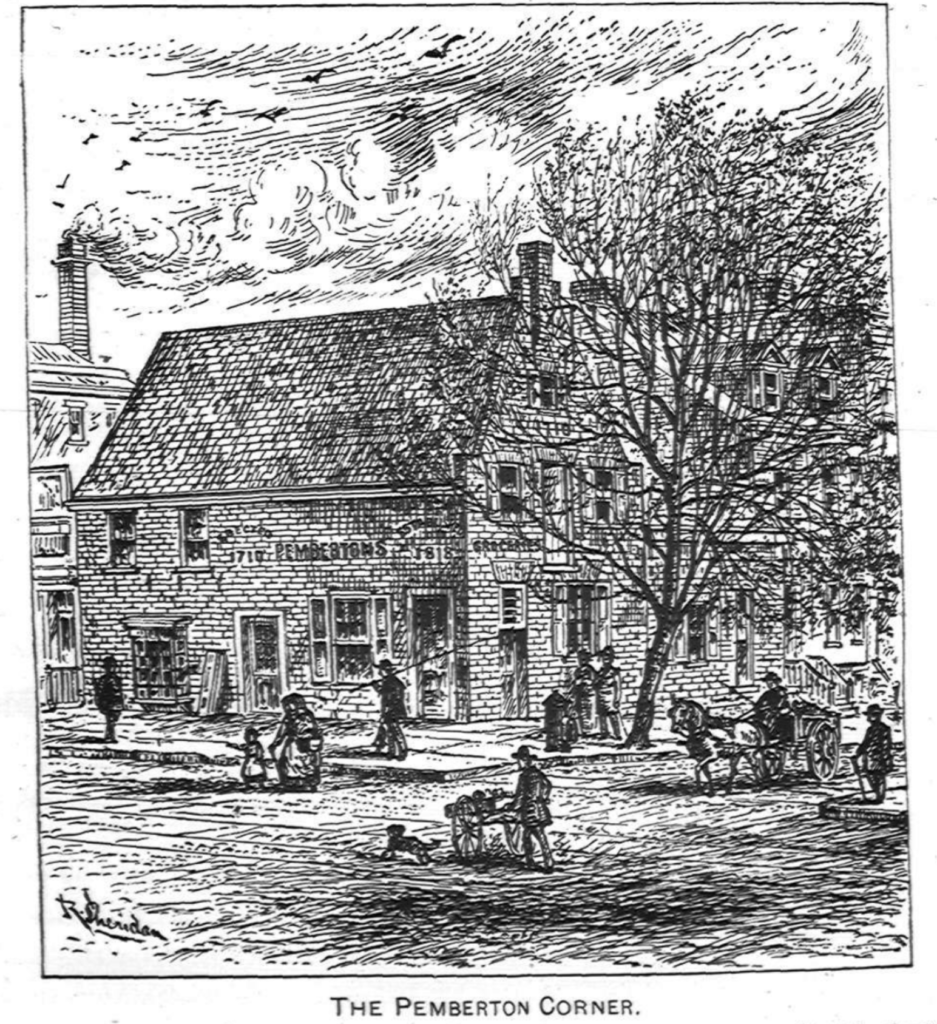

We have a stunningly detailed photograph of Pemberton’s from 1887 or so; unfortunately, the tablet doesn’t appear to be very visible in this view – we suspect it’s the small bit of raised granite just to the left of the pole, hidden in snow. The building was destroyed shortly thereafter, in 1893, replaced by the Pemberton Building, which served an expansion of the Albany Business College (already in business next door, as seen in this photo).

A 1914 report in the Albany Argus indicated that this marker was one of three (14, 16, and 28) which were originally “set in granite blocks and 16 inches above the sidewalk, with slope tops to shed water and protect them from wear. With the improvement of Pearl street they have been lowered and are now flush with the walk, and it is only a matter of time when the inscriptions will become obliterated.”

In fact, although bearing the name of the original pattern maker, this one looks suspiciously like a replacement. It doesn’t match any of the other bicentennial markers, and its typeface appears rather modern for 1886. We can’t be certain, but it’s entirely possible.

Starting with the Lansings

Lansing family genealogies are confusing as can be, given their propensity to recycle names. This is the family for which Lansingburgh is named. Different genealogies give different lineages, so figuring out which sons belonged to which parents it challenging. In fact, based on the sources we were able to find, we would not say with any confidence just how the Lansing line descended. All sources seem to agree that the first Lansing to come to New Netherlands was Gerrit Frederickse Lansing, a baker who came from Hasselt in the province of Overijssell, Holland, in 1640. After that, timelines and his descendants stop making sense, but it appears he had a son Gerrit, a baker who was born in Holland before his parents emigrated. One of that Gerrit’s sons, perhaps, was Jacob Gerritse Lansing (the middle name being revealing of the father’s name in the Dutch naming convention). It would appear that Jacob was born June 6, 1681. He married Helena Glen (granddaughter of Scotia’s Alexander Glen) about 1710, which apparently is when he built a house at the corner of what is now North Pearl and Columbia streets, then just outside the city gates.

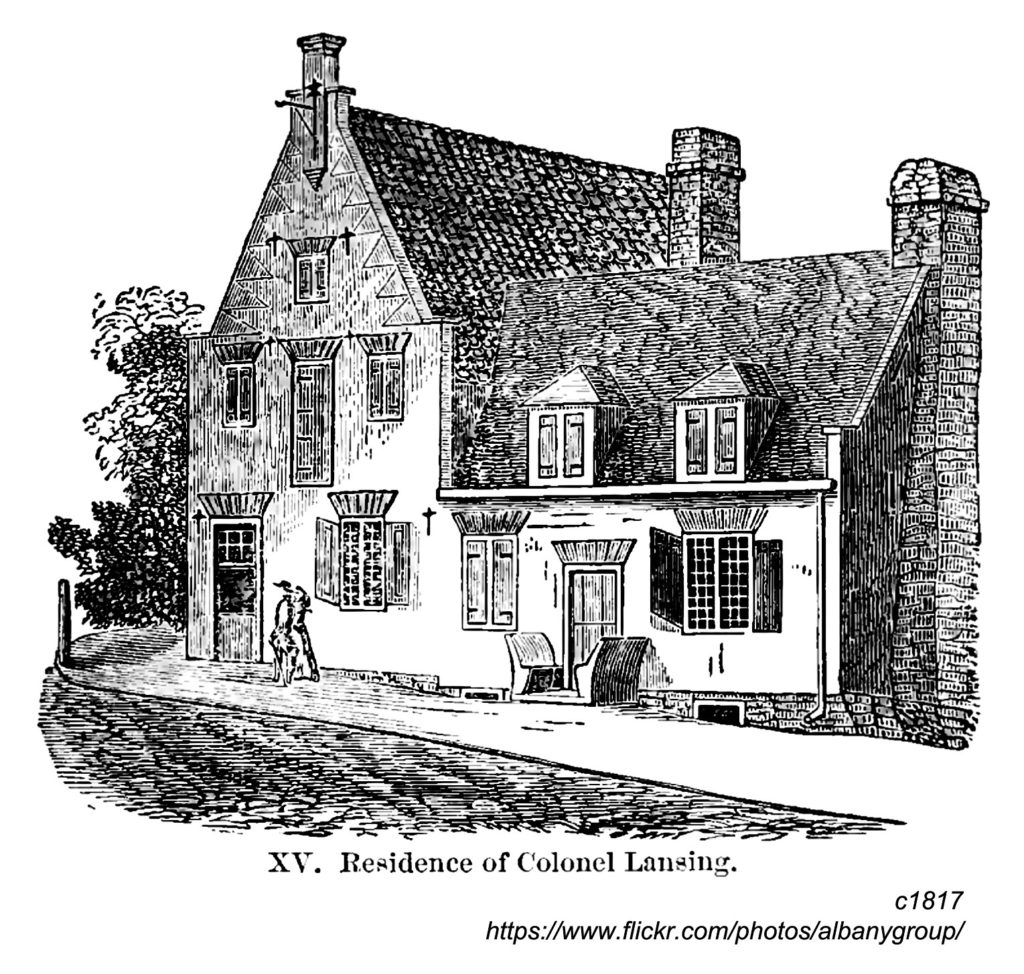

Many sources call that home the Colonel Lansing house – and it is true that Jacob’s son, Jacob J. Lansing, a colonel in the Albany militia during the Revolution, was born there in 1714, and lived there until his death in 1791. But calling it the Colonel Lansing house seems to be confusing one’s Lansings (which is extraordinarily easy to do); Col. Lansing did not build it.

Albany newspaper columnist Charlie Mooney provided a description of the house itself, consistent with several others we’ve found. In fact, some common language suggests a common source for most of the descriptions. every one of which indicates the curious condition of no two rooms being on the same level:

“The structure was of peculiar construction, no two rooms being on the same level, and to pass from one room to another a person had to walk either up or down three or four steps. The windows were originally of small diamond-shaped panes set in lead. The ceilings were not constructed of lath and plaster, but the beams and sleepers, which showed plainly, were polished. The fireplaces were faced with porcelain and ornamented with scriptural scenes. In common with so many buildings of the era, the house had dormer windows, with solid wood shutters fitted to them that certainly most have barred light as well as the fresh air. It was constructed, too, with a high gable roof (another common feature of Albany’s early Dutch houses). The roof was trimmed and fastened with iron anchors, and atop it was a weathervane, another ‘must’ for the Dutch home builders. It had, too, that necessary adjunct of comfort common to the early Dutch regime — the side seats at the front door. In an era when traffic certainly wasn’t what it is today around North Pearl and Columbia, the good Dutch burghers spent a lot of time on the side seats, puffing on their big pipes.”

Diana Waite’s Albany Architecture provides some additional detail: “The parapet gable facade on Columbia Street had fleur-de-lis iron beam anchors that held the brick wall to a timber frame. The brick, laid in Dutch cross bond, formed a zigzag pattern called vlechtwerk (wicker work) along the upper edges of the gable.”

Jacob Gerritse Lansing, the builder of the home, was a silversmith, as was his son Jacob, and his grandson Jacob. (So many Jacobs.) Spoons by the first Jacob can be found in internet searches; the Albany Institute has a silver teapot he made on display. He served various public functions, such as alderman, and High Constable of the Third Ward (in 1704), as well as “surveyor and fyremaster.” The fyremaster was charged with visiting “all voeder [silage] houses and fyreings within this Citty, once in each three weeks, and wherever ye same be held in unconvenient places to fyne ye owner thereof in ye summe of 6s.” He appears to have died in December 1767, aged 86. His son, Colonel Jacob Lansing, appears to have lived in the house until his death in 1791.

Was it ever Widow Visscher’s house?

It is often written that the house passed from the Lansing family to a Widow Visscher, whose first name is never given, who is said to have lodged Native Americans who came to trade at Albany (at a time well past peak trade). She is referred to universally as if she were a known personage, and not a single thing about her is ever revealed. Every story associated with her and her supposed lodgers has some racist tinge to it, so repeat them we shall not, as they seem to have little to no validity. Other stories that speak of Native American trade taking place at the house, even when they don’t involve Widow Visscher, use exactly the same questionable language, suggesting everything coming from a single, unreliable source, which may have been Joel Munsell’s “Annals of Albany.”

In fact, the Albany Argus in 1886 said that the Widow Visscher never lived in this house to begin with:

“A number of years ago, an anonymous writer in Harper’s Magazine pictured Albany as it stood at the beginning of the century. In the Pemberton house he placed the Widow Visscher, a mistake, as her residence was on the north-west corner of Canal and Pearl streets. She afterwards removed to the old yellow house in Columbia street, opposite James, where she died . . . Early in the century it had so far changed its character that a Mrs. Wilson kept school in the wing. For many years past it has been used as a grocery store.”

Perhaps one of the things keeping this legend going is a mural, one of many, at the Dewey Graduate Library of the University at Albany, titled, “Widow Visscher and the Indians,” illustrating the oft-repeated story. It was one of a large number of murals painted by William Brantley Van Ingen of New York City as a WPA project in 1937-38 for the New York State College for Teachers, predecessor to SUNY Albany. A history of the murals suggests that the Widow Visscher may have been Lydia Fryer Visscher, second wife and widow of Matthew Visscher. She is listed on tax assessment rolls in 1799, and in the census of 1800, which unfortunately does not give precise locations, only wards, but does indicate that her household at that time included herself, a younger female, and three slaves. And she did live on North Pearl Street, at what was then numbered 100. (Other sources indicate the Widow Visscher was named Sarah. An 1830 notice from the chancery court speaks of a lot of the widow Visscher that was in the area of “the Gore, and which lies on Green, Division and Hudson streets.”)

The Pembertons

So we know that Col. Jacob Lansing lived in the house until his death in 1791. Maybe Lydia Visscher lived there, probably she didn’t. But we do know the Pembertons bought the building in 1818 and began a grocery business.

Ebenezer Pemberton was born Oct. 9, 1778 in Preston, CT, the great grandson of the Rev. Ebenezer Pemberton, an early (1691) graduate of Harvard who preached in the Old South Church in Boston. With wife Sarah, they had nine children and came to Albany before 1810. Their son Ebenezer Pemberton was born March 1, 1803; his brother John was born in 1807. (We rely on this Pemberton family history.)

The elder Ebenezer is listed as a paper stainer in the city directories from 1814-1818, at 88 and then at 90 State Street, with his house listed as 43 Maiden Lane. We’ll admit we were confused by the profession of “paper stainer,” but we got some clarity upon finding his listing for 1822, when Ebenezer was listed as a “grocer and paper hanger” at 55 Columbia, corner of N. Pearl. So it seems we’re talking about wall paper. (In that same year, Sarah was listed as a milliner at their home at 88 State.)

Based on these listings, and the ages of the sons, it seems likely that the elder Ebenezer established Pemberton’s grocery business, and that Ebenezer and John followed him into the business. Ebenezer senior died in 1823, at only 44 years of age, and that year Ebenezer Jr. was listed as the grocer. Sarah died in 1837, at 58. The business was listed as E. & J. Pemberton by 1838, possibly earlier. Ebenezer Jr. died in 1859.

Early on, Pemberton’s ran a very popular smokehouse, and was noted for its cheese and smoked fish. The business remained in the family for many years. John’s son John Pemberton took over the business at some point; his son Howard worked along with him until he left to serve in the Civil War. John continued until he died July 31, 1885, which seems to have brought Howard back into the business, which he ran until 1892. When Howard Pemberton died in 1928, he was called the last link with the old fur traders.

The Pembertons also owned several lots to the north of their building, and Howard constructed the massive modern building to the immediate north of his family’s historic property, known as the Pemberton Building, in 1886, to serve as the home of the Albany Business College (designed by Ogden and Wright), which previously been in rooms above the Exchange Savings Bank on Broadway starting in 1857.

Even before Howard Pemberton retired in 1892, concerns were raised about the future of the old Lansing home. There was a plan for the building to be acquired by John G. Myers, who offered it to the Albany Press Club as a home for their activities, but they declined. There was talk of turning it into a museum, although not at that site – the proposal was to move it up the hill to a spot on Eagle Street opposite the Capitol, as part of a much larger museum that would include the Van Vechten hall property, the Douw Lansing property, and more. It would have a frontage of 200 feet on Maiden lane, 75 feet on Eagle, and “some” on State. It would front on the Capitol Park and would “cost some money, even a great deal, all things of the kind do.” That, of course, never happened.

Instead, in 1893, the Lansing house was demolished, and the Albany Business College was extended with the building that stands on that corner to this day. (ABC remained there until 1933 when it moved to Washington Avenue.) A brief on the Lansing-Pemberton house written for the Historical American Buildings Survey in 1937 said: “The building has been destroyed, but there is in the possession of Mr. Andrew L. Delehanty, 455 Ontario Street, Albany, New York, an original pediment from the door of this house and also one of the iron anchors used to fasten the construction work to the supporting walls.” Whether any of those artifacts survive would be interesting to know.

We do know that the Albany Institute has tiles that came from the original fireplace, depicting biblical scenes:

Legacy

The Lansings, the Widow Visscher, and the Pemberton family all had one thing in common beyond their connection to this corner – they or their families all owned slaves. While we haven’t found any mention of whether the Jacob Lansings owned slaves, the Lansing family certainly did; Abraham Lansing owned a number of enslaved people. Lydia Visscher we’ve already noted owned three slaves. And while we have not found indications as to whether the grocery Pembertons owned slaves, as they established their business fairly close to abolition in New York, their family did. In fact, the Pembertons were connected to the Livingstons in founding Princeton, which has acknowledged the taint on its founding trustees Ebenezer Pemberton Jr. (not our Ebenezer) and Peter Van Brugh Livingston, brother of Philip Livingston, Albany’s signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Pemberton Corner

“Pemberton Corner” is a name that was lost with time, but we’re not clear just when it faded away. The Pemberton Building that housed ABC was purchased by a Brewster, and was known by that name for several decades. But even though the Pembertons had been gone and the building demolished for nearly 40 years, in 1930 Whitney’s Department Store was selling a line of women’s hosiery under that name:

Leave a Reply