As noted before, until what is now known as the Livingston Avenue Bridge opened in 1866, Albanians or Greenbushians who wanted to cross the river could either take a ferry or wait for winter. Then the railroad bridge near Livingston Avenue opened … and as long as it was the only bridge, it was just “the bridge.” It didn’t need a designation, such as the North Bridge, until another one was built and added some confusion. That was first just called the “new” bridge, then the South Bridge, and eventually the Maiden Lane Bridge. For nearly a century, this swing bridge was part of the Albany riverscape, but it appeared almost quietly and was taken away with hardly a notice.

In March 1869, the Albany Evening Times wrote about the coming addition:

“The new bridge will soon be commenced, and will be completed this year. When it is completed a new depot will be erected on the grounds bounded by Montgomery, Quackenbush, Water and Columbia streets. The new depot will also accommodate the Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad, and probably the Delaware and Hudson’s Albany and Susquehanna Road. The bridge will be of iron, and will not only accommodate the railroads but also foot passengers [which the North Bridge did not]. It will cross the river between Maiden lane and Exchange street, and land between the Boston and Hudson River depots. It will cross Maiden lane at Quay street at a sufficient elevation to allow vehicles to pass beneath it. The old bridge, at the north end of the city, will also be raised at Broadway sufficient to allow vehicles to pass under it, and nothing but the passenger trains for the West and East will cross the surface of Broadway at that point. This change will be owing to the excellent management of W.H. Vanderbilt, Esq., and we feel assured it will be duly appreciated by our citizens.”

W.H., by the way, was William Henry “Billy” Vanderbilt, the son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. He was the still only a vice president of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad (becoming President in 1877).

Later that same year, the Albany Evening Journal reported that the New York Central Railroad track had been extended from the Northern Railroad at Columbia street to Quay street, “a portion of the old freight houses on Quay street having been torn down for the purpose. The track has been laid along the dock on Quay street from Maiden lane to Columbia street, and it will also be laid from Columbia street to the elevator. The object of this extension is to enable the cars to receive cargoes of coal, iron, etc., directly from the boats. It will also be convenient in bringing materials for the new bridge.”

Early in 1870, the Evening Times reported that the contract for building the substructure of the new bridge had been awarded to Charles E. Newman of Hudson. “The new bridge will be shorter than the present one, and will terminate at the old depot in Maiden lane.” Later in the year, The Evening Times gave a thorough description, reprinted in the Sept. 22, 1870 Troy Daily Whig, of the “second great highway over the Hudson at Albany.” Since we first published this entry, we’ve come across a later article that gave some differing particulars and identified the bridge as the work of the Phoenix Bridge Works; for that updated detail, look at this entry. Nevertheless, this is what the Whig wrote in 1870:

“The bridge starts from a point at or near the west end of the old Hudson River Railroad passenger house in East Albany. It runs thence in a straight line 1012 feet until it strikes the Pier, at a point about 100 feet north of the State street bridge, thence it curves rather sharply to the north over the Basin, crossing Maiden lane and Quay street diagonally, and passing through the building on the northwest corner of Maiden lane and Quay street, runs into the old Central Railroad yard. The line then runs through what was the Central ticket office, intersecting the main track near the Delavan House.

Across the main channel of the river are four piers, with 185 feet span, and a swing or “draw-bridge,” 272 feet long and 185 feet from the Pier. There are seven spans of 70 feet each across the Basin, which makes the total length from end to end, including the approaches, 1550 feet. The bridge is to be 30 feet above low water mark. Across the main channel the bridge is perfectly level, but after leaving the Pier there is a fall of 2-1/2 feet to get into the yard.

The entire superstructure is to be of iron of the very best quality,. The bridge is to be double tracked and on each side will be a foot bridge six feet wide. The swing-bridge will be constructed in the most approved style, and will be operated by a small steam engine, to be located at the top of the bridge, over the turn-table.

At present two of the piers on the Greenbush side are nearly completed. Work has been commenced on all the others, and masonry on about half of them. There are now 150 men employed, and it is expected the bridge will be entirely completed and ready for use in about sixteen months, or the 1st of January, 1872. When this bridge is done, it is the intention to replace the superstructure of the old or ‘upper bridge’ with iron, which was the design when originally built. This bridge is to be used exclusively for passenger trains, and the old one for freight.

The President of the Bridge Company is Horace F. Clark, Esq., of N,.Y., the son-in-law of Commodore Vanderbilt; and the Vice President, Chester W. Chapin, of Springfield, Mass. The contractors who are doing the work, are for the sub-structure or mason work, Charles E. Newman of Hudson, N.Y., and for the super-structure or iron work, Kellogg, Clarke & Co., of Philadelphia.

The entire cost of the bridge will be $1,000,000, and when completed will rank as one of the wonders of the world.

We are under obligations to Chief Engineer Hilton for information furnished and courtesies extended.”

That last was a reference to Charles Hilton, chief engineer of the Hudson River Bridge Company, who had first surveyed for a bridge across the river fifteen years before in anticipation of creating “the last connecting link to an uninterrupted railroad communication from the Atlantic to the Pacific.” That initial effort was delayed by court actions. But construction finally made progress and, according to Arthur Weise, the first train crossed on Dec. 28, 1871. The Maiden Lane Bridge was open.

The bridge and its pedestrian walkway, which created an important connection for those traveling on foot or by bicycle, operated for nearly a century. But then came the collapse of passenger rail in the United States in general, and in Albany specifically. With the closure of Union Station in 1968, the Maiden Lane Bridge no longer served a particular purpose. Its tracks, and most of the tracks in that area, were a major impediment to the plan to build an interstate highway along the river, and so the bridge’s days were numbered, and the numbers weren’t high.

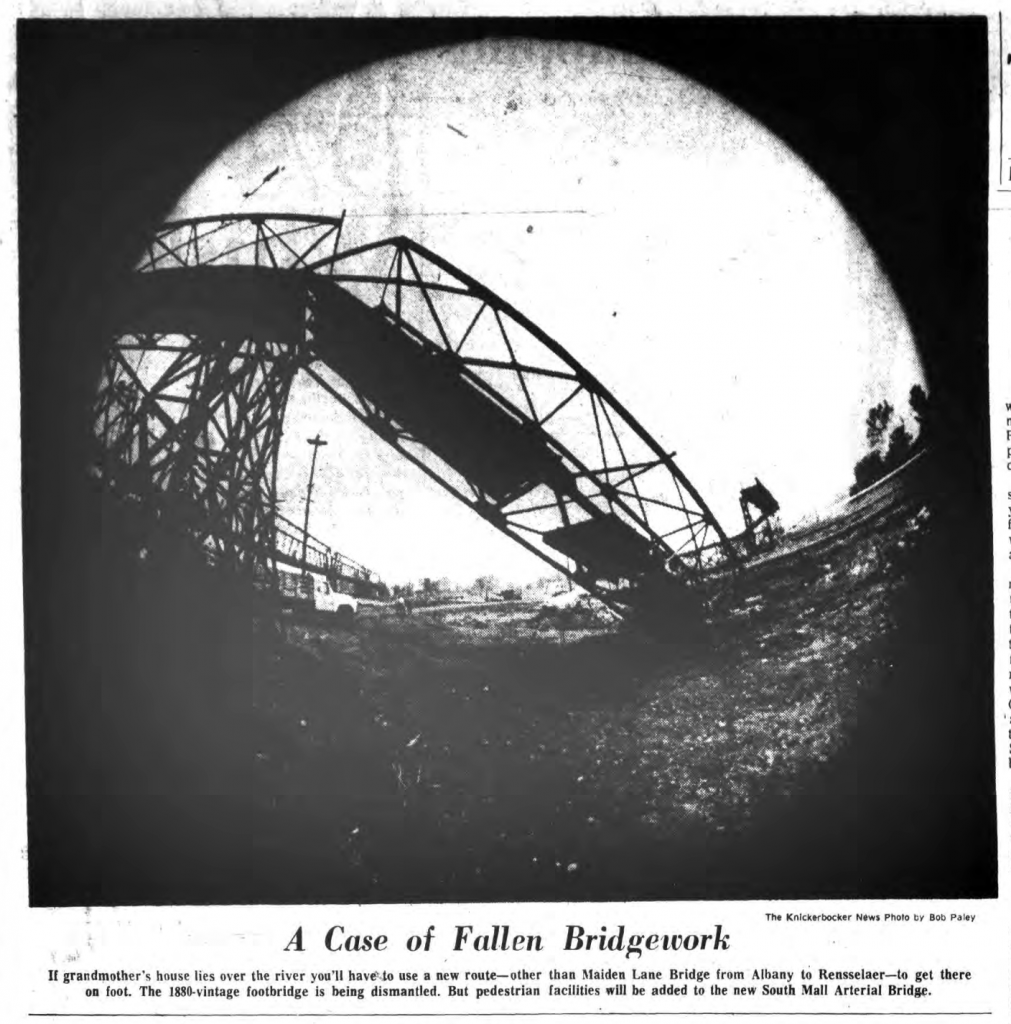

Was there an outcry over the scrapping of what was once considered a wonder of the world (at least by some in Albany)? Not much. In March 1969, A planning agency called the Hudson River Valley Commission criticized the lack of mass transportation planning in the Capital District at the same time it approved the demolition of the bridge. “Before formally reviewing any further Department of Transportation projects for this area, the commission will request a statement of how the projects relate to mass transportation planning for the Capital District.” In other words, we’ll let you eliminate any hope of Albany ever having passenger rail service again, but don’t let it happen again. A Troy Times Record article from November 26, 1969 noted that the bridge would be demolished within the next 10 days, as part of the contract of the Peter Kiewit Contracting Company’s work constructing portions of the Riverfront Arterial. Demolition was to be completed by the middle of January, 1970. The walkway had already been dismantled, back in September of 1968.

Leave a Reply