We talked a little bit about Edward Delavan and his role in developing the temperance hotel that became Albany’s premiere gathering place for 50 years before it burned spectacularly, but his life deserves a little more examination. As noted before, Edward Cornelius Delavan was born in a place called Franklin in 1793. (One biography says Franklin was in Westchester County, of which I find no proof; another says it was Franklin, PA, which is out in the western part of the state.) His father died when he was relatively young and the family moved to Albany. Delavan apprenticed to a printer, Whiting, Backus and Whiting, from 1802 to 1806. They were the publishers of the Albany Centinel until 1806, when for unknown reasons the Centinel ceased publication and was replaced by a paper with the unlikely name of The Republican Crisis. Possibly during this transition, Delavan left and went to Rev. Samuel Blatchford’s school in Lansingburgh for two years (All this according to American National Biography). After that he clerked in his older brother’s wholesale hardware business, rising to partner and then moving to Birmingham, England in 1815 to become the firm’s import agent.

An effusive tribute to Delavan in Winskill’s The Temperance Movement: And Its Workers, Volume 1 wrote that the Delavans were Huguenots who came over with the others who left France for a home in the new world. It said that Delavan came to Albany in 1802, and that “The first book he read, after the New Testament, was the Life of Benjamin Franklin, which led him to choose the trade of a printer, and he entered the office of the Albany Daily Advertiser, which at that time was published by Whiting, Backus, and Whiting. Here he labored for four years.” [Actually, the Advertiser doesn’t appear to have existed at that time, first being published in 1815, but the Centinel did.]

This biography claims that Delavan was the first American (“other than diplomatist”) to land in Liverpool after the declaration of peace in the War of 1812, and that he spent seven years in Birmingham, where he became intimately acquainted with Washington Irving. In 1822 he returned to America, and established a hardware importing business in Hanover Square in New York City. It is mentioned that the Erie Canal’s opening led to extensive trade, but this story doesn’t recount that he made money in real estate as a result of the canal’s opening. “Having been eminently successful in business, Mr. Delavan retired to Albany,” in about 1827, and moved to Ballston in 1833. Was the hardware business then so lucrative that the average dealer could retire by the age of 34? Not quite.

I’m not sure it’s quite forgivable, even given the spirit of the temperance movement, that The Temperance Movement omits just exactly how Edward Delavan got so rich: he imported wine. Lots and lots of wine. But somewhere along the line he had a change of heart about wine, and told that story that his “attention was directed to the temperance question by the example of a drunken servant, who was reformed by signing the pledge, and became a useful citizen . . . [Delavan] found that out of fifty of his early acquaintances no less than forty-four had been utterly ruined by intemperance.” Delavan became a very vocal advocate of temperance. He led the State Temperance Society for several years, paid to launch the American Temperance Union, and bankrolled extensive printed literature on the subject. His efforts led to New York’s brief flirtation with prohibition in 1855.

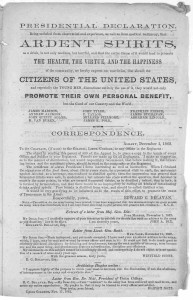

Even among temperance advocates, his zeal was extreme, as he fought against wine (even communion wine) at a time when most advocates were only concerned with hard liquor. He famously accused Albany’s brewers of using diseased water, attracting a libel suit; the facts, however, were on his side. He had or made significant connections on a national level; his “Presidential Declaration” regarding ardent spirits was signed by James Madison, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, James K. Polk, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan and Abraham Lincoln. He spent years collecting the signatures. Some of his correspondence with Lincoln is preserved in the Library of Congress, as are the tracts he was permitted to send to the Union troops imploring them to avoid drink.

Even among temperance advocates, his zeal was extreme, as he fought against wine (even communion wine) at a time when most advocates were only concerned with hard liquor. He famously accused Albany’s brewers of using diseased water, attracting a libel suit; the facts, however, were on his side. He had or made significant connections on a national level; his “Presidential Declaration” regarding ardent spirits was signed by James Madison, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, James K. Polk, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan and Abraham Lincoln. He spent years collecting the signatures. Some of his correspondence with Lincoln is preserved in the Library of Congress, as are the tracts he was permitted to send to the Union troops imploring them to avoid drink.

“Mr. Delavan printed upwards of one thousand millions of pages of temperance literature – more than enough to wrap the whole of our earth in paper.” He carried his mission overseas, even meeting with King Louis Philippe of France. He appears to have devoted his entire life to temperance, until he died on Jan. 15, 1871, at the age of 78. “To the surprise of many, he left nothing to the antiliquor movement and gave his property, valued at $800,000 to $1 million, to his family. Liquorless towns in Wisconsin and Illinois were named in his honor.”

Leave a Reply