Most folks in Albany are probably at least familiar with the name of the Dudley Observatory. Those who still remember when it was in Albany remember its second location, on South Lake Avenue, but that was not its premiere location — it was originally set high up in Arbor Hill in a place still known as Dudley Heights. The Annals of the Dudley Observatory, Vol. I, published by Weed, Parsons in 1866, which was ordered to be printed and distributed by the Secretary of State in 1865, briefly provides a history of the observatory:

The establishment of this Institution was first proposed in 1851, by Dr. James H. Armsby. The plan was submitted to Thomas W. Olcott, Esq., who was the first to promise to aid the enterprise. Prof. Amos Dean became interested in the project, and wrote to Prof. O.M. Mitchel of Cincinnati, for advice and cooperation.

Mitchel immediately offered himself for the job – “If I had control of such an Observatory as you propose to build, I think great progress could be made in this department of progressive science.” Olcott, William H. DeWitt and Ezra P. Prentice each put up $1000, and then Olcott presented the plan to Mrs. Blandina Dudley, widow of Charles E. Dudley, who put up $12,000 and got what we would now call naming rights. Further subscriptions in the city raised $25,000, and the Legislature granted an act of incorporation in March 1852. Prof. Mitchel selected a site and General Stephen Van Rensselaer donated the land on which the Observatory building was erected, what is now Dudley Heights in Arbor Hill.

The building was completed in 1854, and its benefactors provided even more cash to fit it out with instruments, including another $13,000 from Mrs. Dudley, $10,000 from Olcott, and others. Formally, the Observatory was inaugurated August 28, 1856, at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science; a eulogy to Mr. Dudley was delivered at that event, and Mrs. Dudley ponied up another $50,000 for a permanent endowment. In all, she provided $105,000 to the effort. (This inauguration came just one day after a similar event for the Geological Hall.)

What did the Honorable Charles E. Dudley do to merit this long-standing recognition? His eulogy, contained in the Annals, hardly gives a clue. It speaks of his “devoting some years to the pursuits of commerce, in which his labors were rewarded by abundant success,” after which he retired from active business “and became a citizen of Albany, where he was allied by marriage with one of its most respected and influential families.” Born in England to Loyalist parents who had fled the colonies, he came to the newly United States with his mother in 1795. He came to Albany somewhere around 1812, engaged in business, whatever that may have meant, and married Blandina Bleecker. Through his Bleecker connections, he became part of the Albany Regency, serving several terms as Mayor of Albany before he became a State Senator, and, when Martin Van Buren resigned his U.S. Senate seat to become Governor, Dudley was elected to fill the Senate vacancy. He served a term and then retired to Albany.

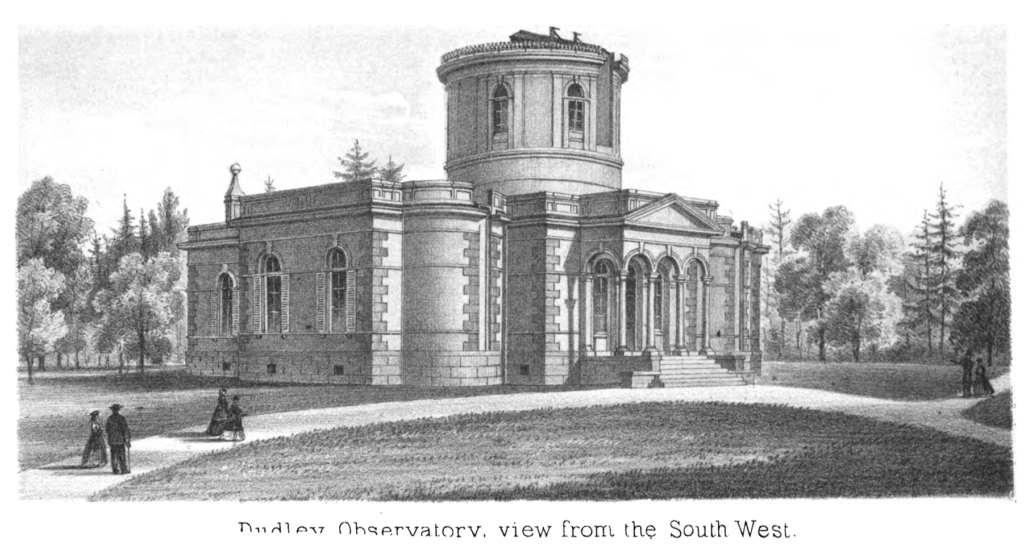

The building erected in honor of his interest in astronomy was the subject of this detailed description in the Annals:

The Dudley Observatory is situated in the northwestern portion of the City of Albany, on an elevation, about 150 feet above the mean tide in the Hudson River. It is distant from the flagstaff on the State Capitol 4931 feet, and the bearing of the latter is 23°18′40″ S.W. from the center of the dome.

The site for the building is probably one of the best that could have been chosen in the vicinity of the city; being easy of access, and at the same time sufficiently remote, as to be free from every disturbing influence. The horizon is clear and unobstructed in every direction, and the position is such as to preclude all possibility of interference, if in future years, the adjoining lands should be occupied for building purposes.

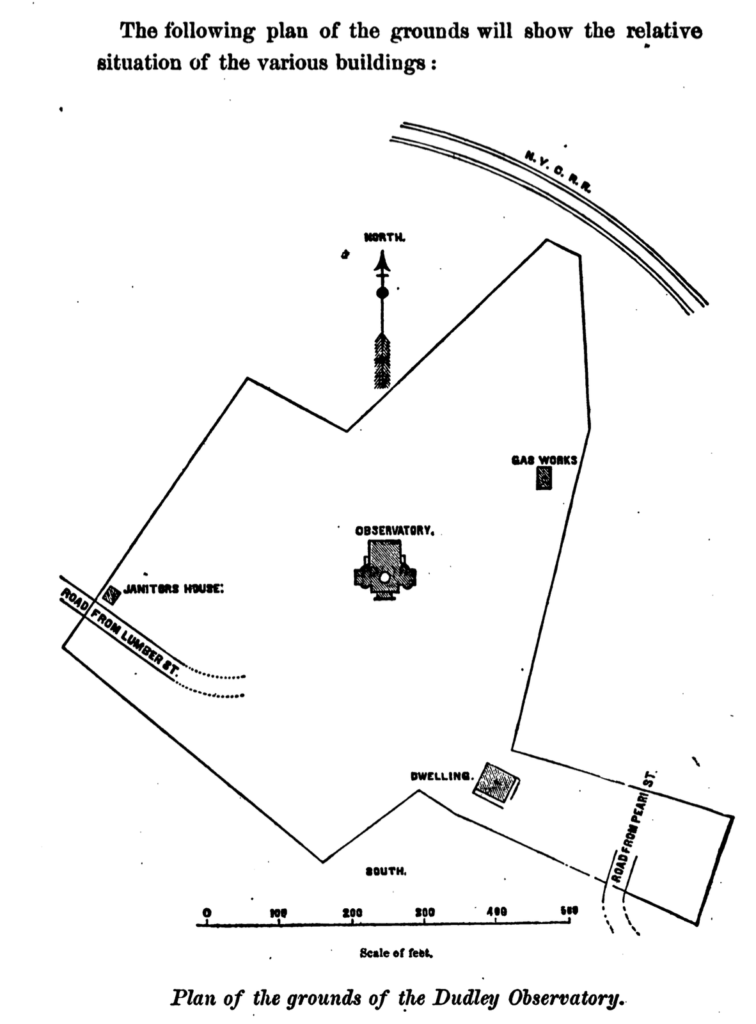

In the plane of the meridian we have an uninterrupted view to the south for more than 12 miles. And we have taken advantage of this circumstance in the establishment of two meridian marks, distant six and twelve miles respectively . . . The following plan of the grounds will show the relative situation of the various buildings:

The grounds have been partially laid out with walks, and several hundred beautiful shade trees have been planted, in situations best calculated to protect the buildings from the influence of the wind.

The observatory occupies the central and most elevated portion of the hill. The dwelling house is situated near the main entrance to the grounds, at a distance of 320 feet from the Observatory. It is built of brick, and is 42 feet by 50 feet; being three stories high, with a basement.

The gas-works, used for manufacturing gas, after the plan of Mr. Aubin, is distant 270 feet, and is about 30 feet lower. The Lodge occupied by the Janitor is distant 380 feet, and stands 10 feet lower than the observatory. The New York Central Rail Road, passes around the northeast corner of the grounds. During the passage of a train of cars, a slight tremor is noticeable when making observations with an artificial horizon, or the declinometer. In fact, so delicate is the latter instrument, that the comparative amount of the disturbance is readily read from the fixed scale, varying from 0″.25 to 1″.5, depending on the distance of the disturbing cause . . .

From a careful and extended series of observations with the Olcott Meridian Circle and the Transit instrument, made especially for this purpose, we have become fully satisfied that this tremor has no appreciable effect on the stability and adjustments of the instruments, or on the accuracy of astronomical observations . . . .”

The text goes on to describe other things that are also barely effected by the railroad, suggesting that perhaps there was a problem after all. But it would be a number of years before the Observatory would move.

Blandina died in 1863. Not surprisingly, she and Charles are buried at Albany Rural Cemetery.

Leave a Reply