The challenge in researching a site like this is that as I try to work on one thing, I get distracted by six or seven other things – as I dug deep through articles about the area’s early airports, for example, I tripped on several completely unrelated articles of interest – and then as I decide whether to pursue those further, I get distracted from my original topic.

This one came about when I was doing some family history research, for the parts of my family that once lived in Amsterdam (New York). I was trying to focus on that, but I was also quite stricken by a headline from the October 25, 1944 Amsterdam Evening Recorder: “No New Developments Today in Story of Native of Amsterdam Being Woman Prisoner of Nazis.”

“There were no new developments today in the reported capture by the Germans of Mrs. Sidney LeGendre, the former Gertrude E. du P. Sanford, daughter of the late Mr. and Mrs. John Sanford, which was announced yesterday by the Berlin Radio and transmitted from London.”

After describing efforts to find her husband, a Naval lieutenant commander on leave from the Pacific and “believed to be in Washington, D.C.,” the Recorder reported,

“As regards Mrs. LeGendre, no fears are felt at present that any harm will come to her. She is a woman of vast and thrilling experiences, a real sportswoman and an expert shot . . . Berlin, in reporting the capture of Mrs. LeGendre as the first American woman taken on the Western front, said she had been on the road to Wallendorf, which the Americans held temporarily, when one of the escorting officers and the driver were hit by gunfire. The other officer waved a handkerchief in surrender, the German Transocean News Agency quoted her as saying.

“The Berlin radio [said she] had come to France ‘as liaison officer between the Allied Expeditionary Forces Club and the U.S. Army.’ A business and legal representative of the Sanford family said that she ‘went to London about a year ago to enter the Red Cross service, and the last he learned she was a Red Cross field worker in the war and had gone to Paris.’ The New York Post said that Mrs. LeGendre had gone to France five years ago with socialite Isabel Townsend Pell, who recently was identified as the legendary ‘Fredricka’ or ‘the girl with the blonde streak’ who was active with the Maquis in Southern France.

“The case of Mrs. LeGendre will be followed with deep interest not only in her native city of Amsterdam, but likewise through the nation because of the prominence she has attained.”

(To my point about getting distracted – In looking up Isabell Townsend Pell, I learned that she grew up at Fort Ticonderoga, when it was in private hands, and was utterly fascinating in her own right.)

To my surprise, I didn’t find any follow-up in the local papers – this story was spread fairly wide, but then there was never another mention of her captivity until it was over. However, I was fortunate enough to find Gertrude Legendre’s 1987 autobiography “The Time Of My Life” available on Archive.org, which is the source for much of this post.

Gertrude, called “Gertie” all her life, was born into an elite family. Her maternal grandfather, Henry S. Sanford, was a world traveler, diplomat, and colonialist. Her paternal grandfather, Stephen Sanford (from another branch of the Sanford family), left West Point to help the family carpet business that his father John had established in Amsterdam. It was Stephen, the son in John Sanford and Son as of 1849, who established a horse breeding farm north of Amsterdam known as Hurricana. Stephen’s son John played polo, raced sculls on Saratoga Lake, served in the House of Representatives and then assumed full responsibility for the carpet mill at 40. John Sanford then married Henry’s daughter Ethel Sanford (in Sanford, Florida). They had three children:, Stephen (“Laddie”), Sara and Gertrude. Gertie was the youngest, born in 1902.

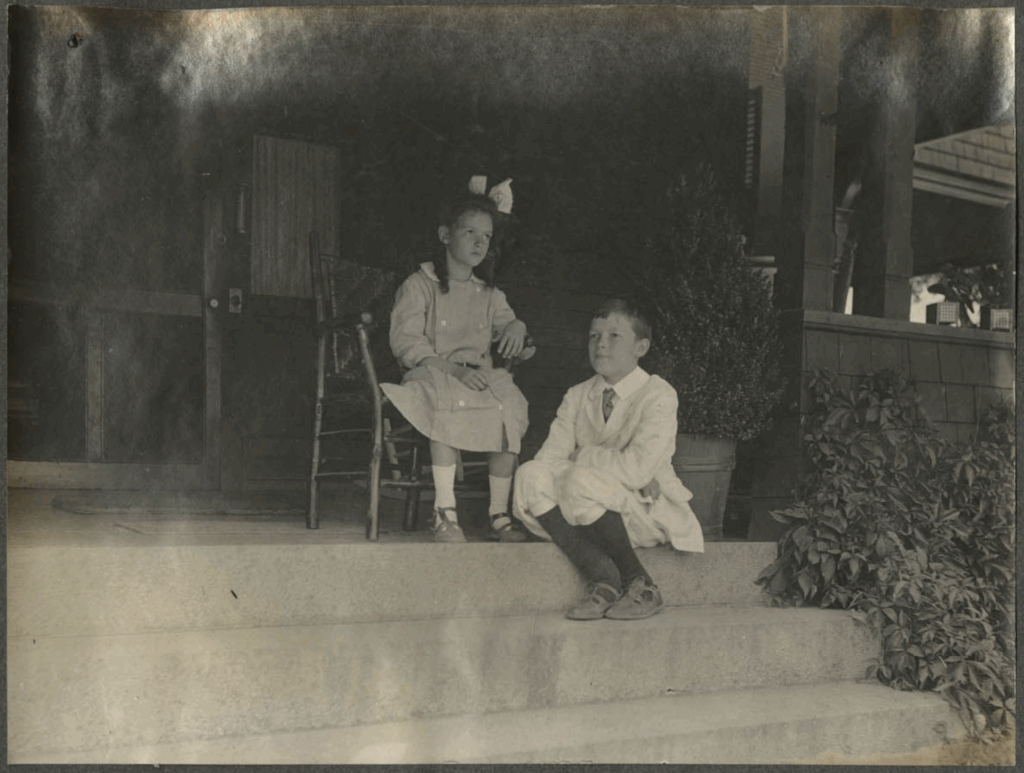

Childhood

“As children, our lives were governed by the change of seasons. From August through Christmas, we lived in Amsterdam, New York. It was said that there were two seasons in Amsterdam – winter and August. I always remember how cold it was skating on the Erie Canal and walking on hard-packed snow with a pair of creepers attached to the bottoms of my rubber boots. Winter came early in Amsterdam, we we’d all had our fill of the cold by Christmas time.” Their “winter” home was in Aiken, South Carolina, where Gertie had been born – Aiken was “a winter home for northern [horse] breeders, riders, hunters and polo-players.” In summers, they would go to Maine or Newport, RI, or France, or England.

“How I dreaded those trips by sea!” she wrote. “Six or seven seasick days aboard the Olympic or the Mauritania there and back. It’s ironic that I sailed in every great passenger ship of this century and was always miserable.” The family was caught in France in the summer of 1914 when war was declared, and “everyone wanted to cross the Channel at the same time.” But they were able to cross and spent several weeks staying at Luffinam Hall, guests of Mr. Robert Strawbridge, Master of the Cottsmore Hounds, before returning to the states.

She wrote fondly of the races at Saratoga, which her father was very involved with and where the Sanford Stakes race is still run. However, beyond the quote above, Amsterdam is not mentioned, and a look through her photo albums also doesn’t provide any pictures that appear to have been taken in Amsterdam; the best we can do is Saratoga.

She also wrote fondly of her mother (who died at the family’s Long Island home in November, 1924) and her more artistic temperament:

“Mother’s European upbringing was felt in the home. We spoke French and most of our governesses were French. Mother preferred it that way since French had been her native tongue while growing up in Belgium. All her life, she spoke English with an accent.”

“Sometimes I think that it must have been very difficult for her to have married my father at the age of nineteen and to have moved to a small factory town in upstate New York. Father was forty-one and to him she must have seemed a child. But if it was difficult for her, she never let on.”

It’s rather unclear how much time the family actually spent in Amsterdam; at the end of his life, John Sanford was reported to still have spent four months a year in Amsterdam. Gertie’s photo album contains numerous pictures of the family at various homes and cottages, including in Saratoga, but none that appear to be Amsterdam. Some time in the mid-teens, according to Gertie, the family moved to New York City, and at the end of the war resided at 9 East 72nd Street. So by the age of 16 or so, Gertie was probably out of Amsterdam permanently, although there were periodic visits, and her mother, at least, remained involved at some level in local social activities. The Amsterdam Evening Recorder continued to report on many of the family’s comings and goings, and specifically reported on Gertie – her doings in Palm Beach in 1922 and 1923; the time she met Haile Selassie, the king of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1929; or the time that same year that she killed a lion. In 1941, the paper wrote that Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Legendre were brief visitors to Amsterdam. “Before returning [to New York] today they were luncheon guests at the Tower Inn, Cranesville.”

Safaris

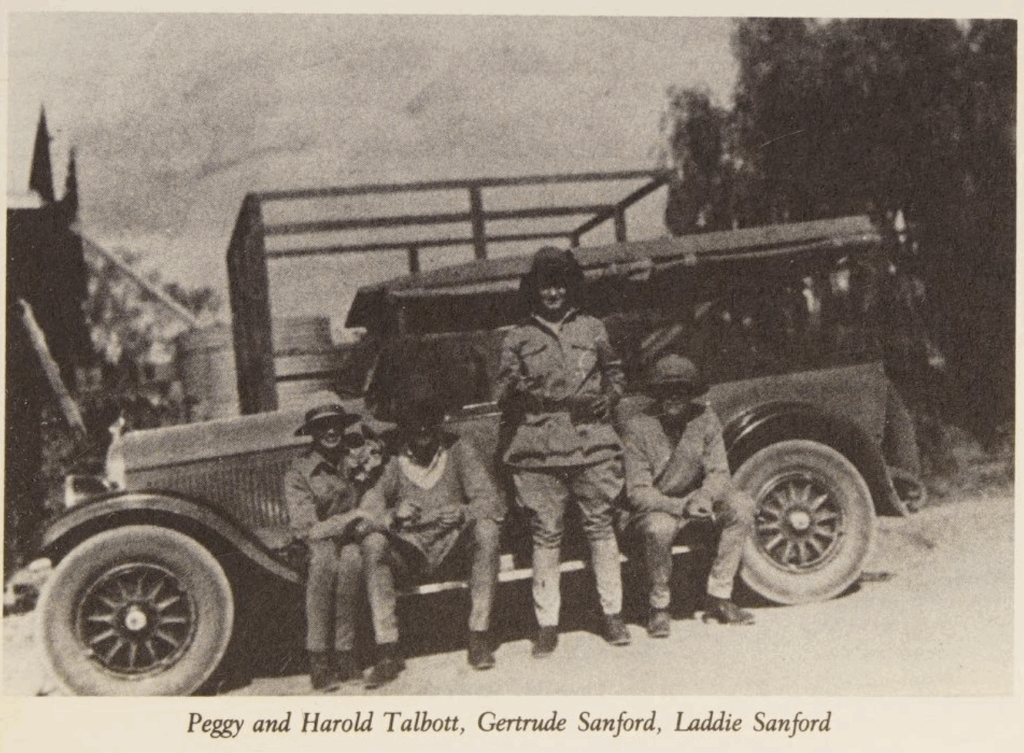

Despite (or because of?) being brought up in mansions and ballrooms and going to the most exclusive schools, she was an avid outdoorsperson and hunter, one who early became obsessed with going to Africa on safari, and while waiting for that opportunity shot everything from birds to elk. She and her brother Laddie went to Nairobi in 1927 with Harold and Peggy Talbott; Harold Talbott later became secretary of the Air Force. She describes a time when wildlife was still remarkably plentiful, and they thought little of shooting it, though their guide insisted they wait for the “right” lion. “Our lion had to have a noble head and black mane. For a week, we saw nothing shootable.” Her first lion kill wasn’t her last, though in her memoirs, recalling a picture taken on a later expedition when she was 24, she said “Today I wouldn’t pose like that for anything, nor would I shoot a lion., but when I look at that picture I do remember that day.” She also killed Cape buffalo and elephants.

On an earlier trip to Egypt, “we had the extraordinary good fortune to be able to go into the tomb of Tutankhamen with Howard Carter, who had just discovered it. I’ll never forget the sight of those treasures piled one on top of the other all the way to the ceiling of the tomb. Nothing had been touched or moved.”

“After my first safari to East Africa with Laddie and the Talbotts during the winter of 1927/28, I decided to go on expeditions for the American Museum of Natural History in New York and bring back specimens for them.” Her proposal somewhat shocked the president of the museum, Dr. Fairfield Osborn, though she was unsure if it was the proposal or the fact that she was a woman. “When he asked me my qualifications, I told him that I had done lots of hunting; that I had just come back from a trip to Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda and that I had shot everything. I also told him that I had hunted in the Cassiars, in British Columbia, for stone sheep, goat and bear, and in Alaska for kodiacs and caribous. I know that I sounded boastful, but I wanted to convince him.”

Dr. Osborn told her that it would cost $30,000 “just to mount such a group in the African Hall,” including the preservation and representation of the specimens and background scenery. “I can still feel the despondence that I had felt that afternoon when I left the museum. Thirty thousand dollars, plus the expedition expenses, was indeed a roadblock, but I’ve never been one to be stopped. I went to my father to ask for the money.” Ahh, the struggle.

“There was only one way to put my request. ‘Papa, how would you like to give me a present equivalent to the polo ponies you give Laddie [her brother] from time to time?’ I asked. At first, he pretended not to hear me. I explained that I wanted to go to Abyssinia to collect a group of giant nyala for the African Hall of the Museum of Natural History. He made me repeat myself. Then he asked me simply, ‘You are very keen to do this, aren’t you?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Well, my child, that seems fair. The cause is worthwhile. I believe in museums with mounted groups for the public to enjoy. If I give Laddie presents, I will do so for you, too. If that’s what you really want, I will give you the money.’ I can’t remember if I hugged him. I must have. I was elated.”

It was in Ethiopia (she said she preferred the name Abyssinia for its biblical, Christian reference) that she met the regent Haile Selassie, who came fully to power in 1928. “His Majesty was shocked when I told him that I’d shot five lions in Tanganyika. He’d never heard of a woman hunting.” He gave her the gift of a silver grey mule from the royal stable, which joined the expedition.

After a successful hunting expedition and return to Addis Ababa, she realized she was in love with Sidney Legendre, one of a pair of New Orleans socialite brothers she traveled with, and they were married in a society wedding in New York City, with the Rev. Dr. Edward T. Carroll of Amsterdam’s St. Ann’s Episcopal Church presiding. Her life continued to involve tennis and travel and a South Carolina plantation called Medway that they bought in 1930, and another expedition for the museum (Viet Nam this time, which she called Indochina). More trips to Africa and the Middle East, more animals killed and brought back for exhibition.

Captured by the German army

Her war experiences are written of rather briefly, or with rather less detail than I would like. She starts by saying, simply,

“When the U.S. became involved in World War II, Sidney joined the navy and was assigned to the Pacific. I was also determined to join the war effort, so I managed to get myself assigned to Washington during the summer of 1942. My job was to manage the cable desk for the Communications Branch, which was later to be called the Office of Strategic Services – known as O.S.S. – commanded by General William J. Donovan, known to his friends as ‘Wild Bill.’”

She says that a year later she was one of six women chosen to report to O.S.S. offices in London. (No pretense to “Red Cross” duty is made.) She served there until September 1944, when she was moved to Paris, “where the O.S.S. was setting up shop” shortly after its liberation. “General Eisenhower wanted us all under his command, so I donned the uniform of a WAC second lieutenant. I didn’t even know how to salute.”

The O.S.S. offices were not ready, and staff were given a leave. In a bar she had visited before the war, she “was immediately surrounded by a group of war correspondents who were on their way to Luxembourg where the U.S. Third Army had its headquarters. All they could talk about was the front. Each one of them wanted an exclusive, prize-winning photograph and wanted to see the war firsthand. I envied them.” Then she spotted an O.S.S. member named Bob Jennings in the crowd. “I didn’t know exactly what he did, but knew enough not to ask . . . When we discovered that we both were on leave, we immediately began scheming to get to the front and back in five days. I don’t know which of us came up with the crazy idea first.”

They took an unreliable Peugeot and headed for Luxembourg. Their car broke down, and they were stuck waiting for a repair when a friend of Jennings came into their hotel, a Major Max Papurt.

“Papurt smiled and lit a cigarette as I told him how eager I was to see the front. He invited us to go to Wallendorf with him to interrogate some German prisoners. Wallendorf was just over the border, about forty kilometers away. I answered his invitation by standing up.” She notes that at this time, “the front line shifted hourly, but things seemed under control.”

As they approached Wallendorf, they were hit by sniper fire, with their driver and Papurt wounded; they tied a white handkerchief to a rifle to surrender. “We quickly burned our O.S.S. identity cards, but I decided to keep my first aid certificate, passport and AGO [standard military identification] card which gave me the rank of lieutenant. I asked them what they would tell their captors. Papurt said that he would pose as an ordnance officer and Bob would claim to be a naval observer. I would pose as a file clerk on leave from the embassy in Paris.”

They were held in a prison camp for a few days, thinking they would quickly be released, but then “I sensed a different feeling in the air, as though I were suddenly considered a dangerous spy instead of a crazy American girl who had come too close to the front lines while on a lark.” Imprisoned in Castle Dietz for some weeks, it appeared she would be sent to a concentration camp in Czechoslovakia at the end of the year, but ended up being sent to Bonn and held at Godesberg with a group of WWI French officers who had been rounded up on the occupation of Paris. In March, they were moved and moved again as the German army retreated.

It appears that a friendly German officer who was her captor for a time, and who had spent 18 years living in the U.S., may have arranged for her to be delivered to Switzerland from Konstanz late in March 1945. There was a hitch in the plan, a lack of needed orders from Berlin, and with no telegraph or telephone communications, no way to get them. She had to get aboard a crowded train and hide herself until it made the border.

“It seemed that the train would never start. A trainman started through the car, swinging a lantern to inspect the empty seats. I rose quickly and headed for the toilet. Inside, I locked the catch and leaned heavily against the door and swallowed my pounding heart. I heard footsteps approach and stop, and finally continue and die away.

When the train began to move, I slipped out and settled between the seats once more. The train inched its way painfully along the tracks. At last it jerked to a halt, and I moved slowly to the door. Up the platform, I spotted white gates in the moonlight. It was the frontier, but the train had stopped short of it!

Slowly, I descended on the other side of the track and forced myself to walk slowly into the shadows of a line of empty freight cars standing next to my train. As I neared the last one and was ready to make a dash to freedom, I suddenly sensed someone at my side. I froze and turned to see the man in the light-colored coat that I had seen on the platform at Kostanz. ‘Run,’ he said.

I started to run and heard a whistle behind me. Someone shouted ‘Halt!’ I kept running, my shoulder bag banging against me as I headed for the gate. I heard footsteps behind me.

‘Identitée! Identitée!’ the Swiss border guard shouted from the gate.

‘American passport!’ I screamed and passed under the lifted barrier.

A German border guard stopped on the other side, bellowing with rage. I still don’t know why he didn’t shoot me as I ran. Perhaps something had been arranged. I’ll never know. Freedom was enough.”

She further wrote, “The irony of my situation was that all the time that I was imprisoned, I believed that people were working hard to get me out. In fact, they had drawn a line through my name and had acted as if I had never existed. That was the preordained fate of any O.S.S. member who fell into enemy hands. To this day, I don’t know who arranged for my release/escape. I’m not even sure if it was meant to be such a close call.”

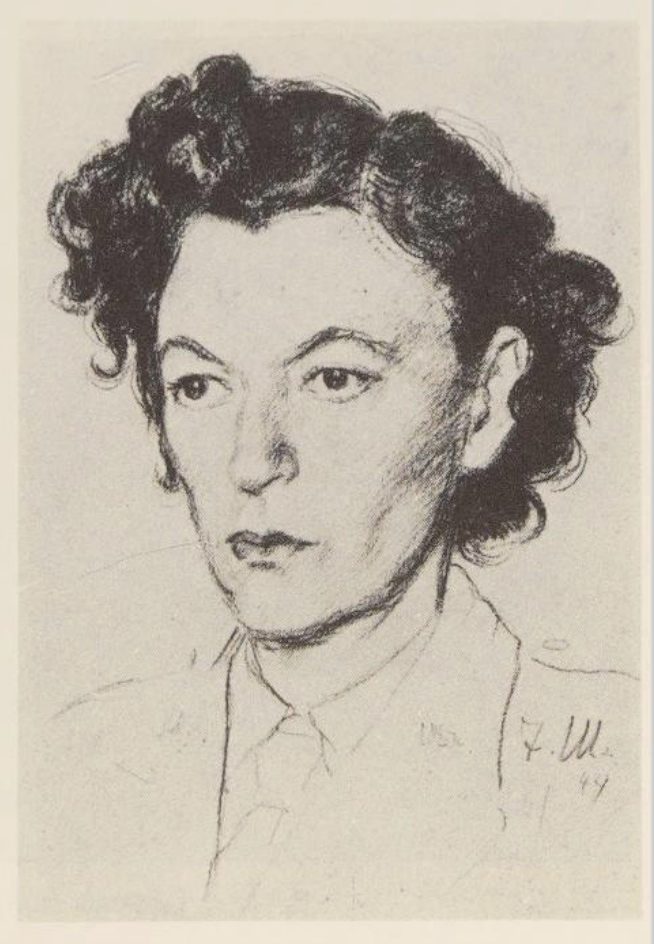

Interestingly, after an initial flurry of articles about her capture, there is simply nothing in the newspapers about her for the duration of the war. Perhaps that reflects the O.S.S. policy, and either lack of curiosity or cooperation from the press. Even in the wake of the war, the mentions of her imprisonment are brief. One of the few mentions even near that time was in the New York Evening Post from 1945, in Elsa Maxwell’s Week-End Round-Up column:

“Mrs. Sidney Legendre was there [at a dinner party] with her dark, handsome husband, who has been in the navy during the war. ‘Gertie’ Sanford, who always looks like the flying victory of Samothrace, is a trained and superb athlete, a great sportswoman and what is more a heroine, for she was captured by the Germans when her Red Cross car got ahead of Gen. Patton’s Third Army – but she looked so well and slender in a clinging evening gown that it was fun to conjure the difference that can take place in the life of a young woman like this.

‘How do you feel?’ I asked her as she sat munching chicken salad and holding a glass of champagne firmly. ‘Well Elsa,’ she said, ‘it is better than thin black bean soup and rotten bread in a German prison.’”

After the war, it was back to tennis and safaris, a trip to Nepal, meeting Albert Schweitzer. Anyone interested in more details and the rest of her life can find it in her autobiography at the Internet Archive.

It’s remarkable that the papers seem not to have followed up on her months of imprisonment at all, but they had not lost interest in her entirely. A 1946 Saratogian article giving the history of the Sanford family’s horse endeavors gave a mini-biography of Gertrude. In 1953, the Evening Recorder reported in the Social-Personal News section that Mr. and Mrs. Stephen Sanford had cancelled a planned ball at their villa in Palm Beach, Florida, due to the death of Gertrude’s brother-in-law, John Morris Legendre, and his wife in a plane crash in the Gulf of Mexico. Her documented returns to the area all involve presenting trophies at the Sanford stakes through the 1960s.

Sanford Family Legacy

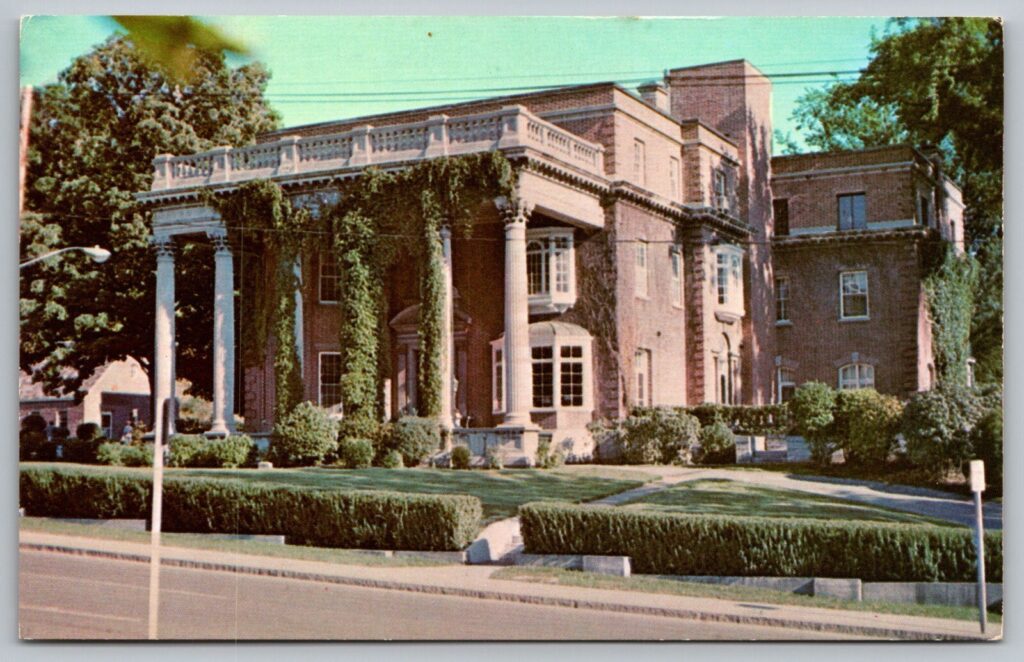

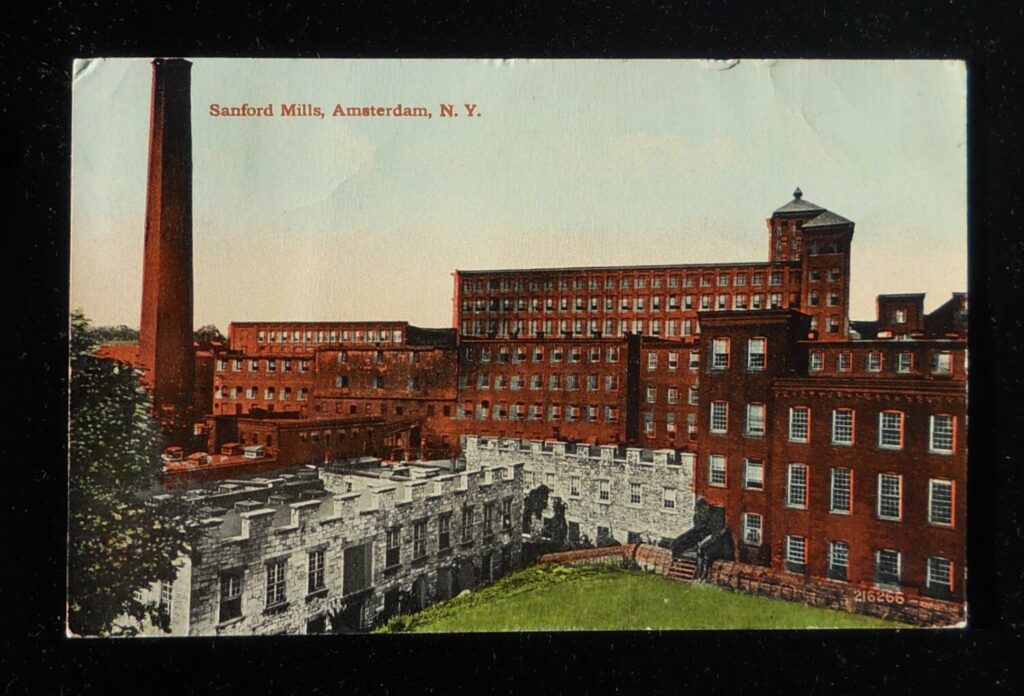

As for the Sanfords – the Sanford carpet company was founded around 1838 by John Sanford, then his son took the company over as Stephen Sanford and Sons; one of those sons was Gertrude’s father John. In 1929, it merged with the Bigelow-Hartford Company of Thompsonville, Connecticut. John died in 1939 in Saratoga and is buried in Green Hill Cemetery in Amsterdam. Several years before his death, in 1932, with his children grown and gone, he deeded the Sanford Mansion, which he had just substantially rebuilt in 1914, to the City of Amsterdam to serve as its City Hall. (The family had already made their mark on the city with the Home for Elderly Women and the reconstruction of the Children’s Home.)

The Sanford stakes are still run at Saratoga. The Sanford Stud Farm still stands, but just barely, and volunteers are trying to preserve this bit of Amsterdam’s history. Stephen “Laddie” Sanford II, “the last male descendant of the family that brought carpet-making to Amsterdam in 1838,” operated the farm “until a disastrous fire in 1939 damaged it to such an [extent] that it never retained its previous prominence,” according to the Gloversville Leader-Herald in 1977, writing about Laddie’s death.

Gertrude died in 2000 at the age of 97.

As for the carpet mills, Bigelow-Sanford closed Amsterdam operations, which included about 40 buildings, in 1955. In 1970, the Recorder said that nearly the same number of people, about 1500, then worked in the complex for a large variety of companies, including Fiber Glass Industries, Noteworthy, Coleco, and a number of textile and electronics companies. The buildings mostly still stand today. They were purchased at auction by Grossman Industries (of lumber company fame) in 1955.

Bigelow-Sanford was acquired by Sperry & Hutchinson Company (of S&H Green Stamps fame) in 1967. After other turn-overs, it was acquired by Mohawk Industries, which also had origins in Amsterdam, and while there are still Bigelow-branded carpets sold by Mohawk, the Sanford name has disappeared.

Leave a Reply