I’ve written briefly before about a building I never saw, and miss all the same: the Albany Savings Bank building on North Pearl Street. This time, despite my resolution to make these postings pithier, I’m taking a bit of a deep dive into the history of the bank and its buildings.

The Beginnings: Saturday Night Deposits

Albany Savings Bank was incorporated March 24, 1820, the second savings bank in New York State. The legislative act named the last Patroon, Stephen Van Rensselaer, as president, in which role he served until his death in 1839. Savings banks were established as mutual associations, not-for-profits that provided a service otherwise unattainable by the poor and working classes. The Argus wrote in 1899, “The need of a safe and reliable depository for the earnings of those citizens who desired to lay by something for the proverbial rainy day was strongly felt. it was believed then, and has since proven to be the fact, that it would tend to make many people more frugal, industrious and thrifty, as well as aid in producing better citizens.” At the time the bank opened in 1820, according to a 1945 history of the bank and another source, the population of the city was 12,630, including 109 slaves (which seems an undercount).

Initially, the bank did not have its own building. It opened for business at the New York State Bank’s offices on Saturday, June 10, 1820. According to the Argus, $527 was placed on deposit on the bank’s first day. The very first deposit, $25, was from silversmith Joseph T. Rice. Also making deposits that day: “a gentleman for his daughter, $45; a seamstress, $40; two mechanics, $22; three apprentices, $1 each; a laborer, $10; a clerk, $5; a lady, $50; a lady for her daughter, $25; another, the same; a [Black] servant, $46; another, $3; a widow, $200; a merchant, $15.” One of those depositors was Adam Blake, father of the proprietor of the Kenmore.

The bank’s first loan “on bond and mortgage” was to its own president, Stephen Van Rensselaer, for $30,000 on his lumber yards and stone mill. The terms were not reported.

According to the bank’s bylaws, deposits could be made only on Saturday evenings, from six to nine o’clock. No money could be withdrawn except on the third Wednesday in January, April, July, and October. Interest was payable in January and July on all sums which had been deposited three months or more previous. A funding committee met each Monday to discuss how to invest the sums deposited the previous Saturday. Lacking their own facilities, the secretary of the bank, in addition to recording the minutes of the meeting, was “to cause to be provided fuel, candles, etc., for the accommodation of the Board of Managers.”

In 1828, the Commercial Bank of Albany agreed to an arrangement where it would take the deposits of the savings bank and do the business without expense, and so it remained until 1871, when the savings bank leased premises at 71 State Street, but that was only until a building was constructed at State and Chapel in 1873. As for that building, “its interior on the upper floor will be particularly remembered as the lodge room for Masonic bodies of this city until in 1895, they built a temple for Masonic purposes only on the site of the first lodge devoted only to and owned by Masons in America.”

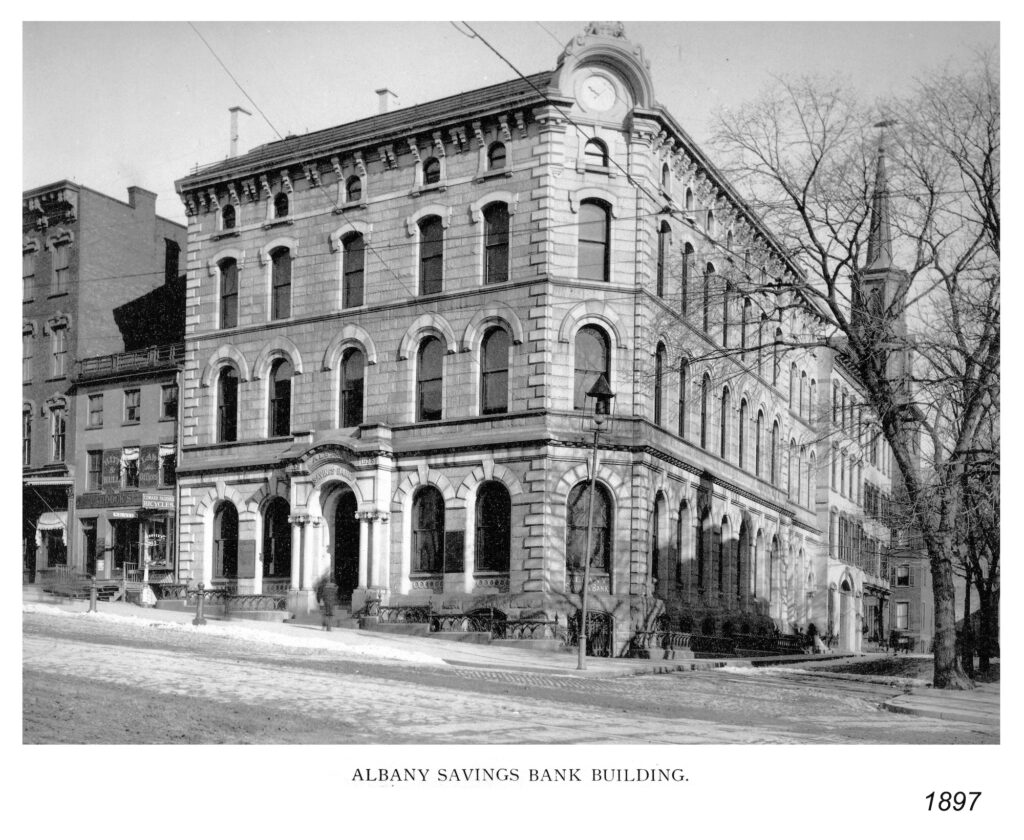

The Albany Savings Bank Building, shown pictured in 1897 courtesy of the Albany Group Archive. This was the bank’s home from 1873 to 1899. The building was then sold to Albany County for court use.

A New Building of Its Own

The Times-Union reported, on Nov. 9, 1895, that the trustees of the Albany Savings Bank “contemplate the erection of a modern banking and office building on North Pearl street. The matter is still in an embroyotic [sic] state, but with excellent chances of consummation . . . The project, if carried to an issue, will give to this city the largest building (the new capital excepted), that she has ever possessed.” Two sites were under consideration, one being the “Nelligar property on the northeast corner of State and North Pearl streets and the Bender property adjoining it on the east on State street.” However, the Bender property was in “a deep sea of litigation” as a result of the will of Matthew Bender; without the two together, the site would be too small.

The other site “is that portion of North Pearl street between the north end of the Tweddle building and Maiden lane. This includes three pieces of property: Old Odd Fellows hall, owned by Mr. P.J. McArdle, the structure to the south, which is part of the Austin estate, and the building at the corner of Maiden lane owned by the Messrs. Morange. The difficulty that stands in the way of a purchase of this property is said to be the high price asked for the Austin building. The frontage on North Pearl is 116 feet and it extends back to the Corning property.”

The existing bank building on Chapel Street, which had tenants including the Albany Gas Light Company and the Albany Insurance Company, had grown too small. There was thought of simply expanding from that site to Maiden lane, but that was rejected. “The banking institution is one of the oldest and soundest in the state and could expend a million dollars on the new structure without any serious effect on its enormous surplus . . . it is argued that the new building will pay a rate of interest much larger than any other investment the bank can make. It would be a substantial and beneficial application of a part of its surplus, and in a direction for the betterment of Albany.”

“Here is the kind of building suggested by one of the trustees of the bank: ‘It will be a modern office building, similar to those in New York city. I have been told that it will be twelve stories high and will be of stone set in a steel frame. It is contemplated that the entire lower floor will be occupied by the bank and that the remainder of the building will be devoted to offices.’”

The Times-Union went on to gush that

“…a new and elaborate banking building for the Albany Savings bank is not only a possible but is, indeed, a probable consummation of the near future, and such a project is made all the more certain when such men as J. Howard King, Henry T. Martin, Matthew Hale, William Kidd, Marcus T. Hun, W.M. Van Antwerp, James D. Wasson, Abraham Lansing, Grange Sard, Rufus K. Townsend, Jacob H. Ten Eyck, W.B. Van Rensselaer, Luther H. Tucker, J.W. Tillinghast, Ledyard Cogswell, Charles Tracey, Clarence Rathbone, Edward Bowditch, and Acors Rathbun are trustees of the institution and behind it.”

The site was decided – between the Tweddle and Maiden Lane – and demolition of the previous buildings there began in May 1896, when there were still plans to build a nine-story structure. “Yesterday the few tenants who remained after May 1 hustled to get out. To a passing observer it seemed as if the building[s] were in an unsafe condition and that the tenants were anxious to vacate before some disaster overtook them.” (Scroll to the bottom of this story for more on who those tenants were.)

That new site, by the way, was once occupied by the “Vanderheyden palace,” the subject of Albany Bicentennial Marker No. 17, which was very well known in the 19th century as the inspiration for Washington Irving’s “Bracebridge Hall.” Following that, from 1833 to 1870, the First Baptist Church was on that location; that was succeeded by “several business blocks.”

“The work will be pushed with all possible speed. The building to be erected will cost about $500,000 and will be a model of architectural beauty and strength. It will cover the entire space between the Tweddle building and Maiden lane and will be eight or nine stories high. It will be occupied in part by the Albany Savings bank, which will be above the ground floor, and by merchants and office tenants. In design it will be similar to the magnificent life insurance buildings in New York. The building will not be ready for occupancy before May 1, 1898.”

The plans that became the iconic Albany Savings Bank building as designed by Henry Ives Cobb of Chicago were quite different from the original intent by the time they were approved in August, 1897. “The plans are complete in every detail and are in fact the most complete and most elaborate plans filed with the department in a long time. The specifications cover 55 typewritten sheets,” the Argus reported. But the plans for a 12-, or 9-, or 8-story building with associated rental space were gone.

The old building at State and Chapel, by the way, was sold to the county to be used as court rooms on Feb. 15, 1896, for $100,000.

The Beauty of the Albany Savings Bank Building

The Argus didn’t spare in sharing the details, and I won’t either:

“Its peculiar style of architecture will make it one of Albany’s grandest buildings. One story high, but with a great round dome, the top of which will be 92 feet 4 inches above the level of Pearl street, which is higher even than the Tweddle building. The logia and the six great columns, each weighing 24 tons, 48,000 pounds, will give the front of the building an impressive appearance. The entrance doors will be 11 feet wide and there will be two large turn-stiles.

“The building will have a frontage of 105 feet 4 inches on North Pearl street, and will extend 87 feet west on the line of Maiden lane. There will be a foundation of concrete, stone and steel, 13 feet below the grade of Pearl street. The walls will be faced with granite and white marble on the two street fronts. The floor and roof framing will be of steel with tile and brick arches, and there will be an asphalt and tile roof. The basement floor will be of concrete, asphalt and pressed brick.

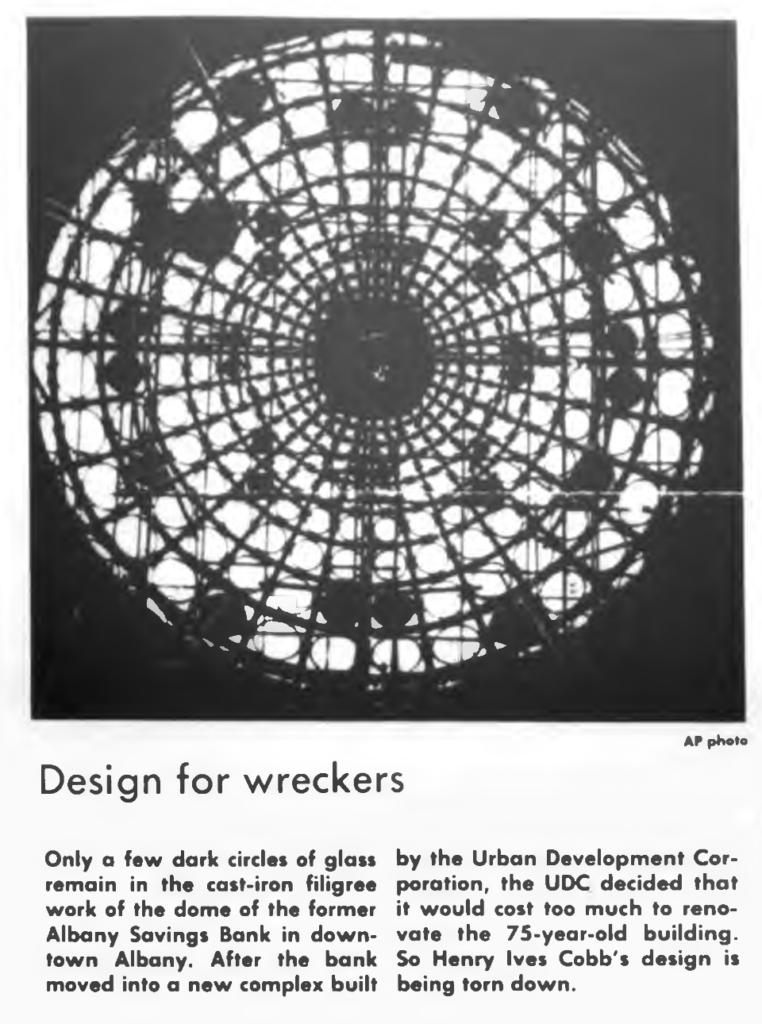

“The first floor will be of marble, and the finish will also be of marble, plaster and bronze. The framework of the dome will be of bronze and iron, and will have clear and translucent glass, which will give sufficient light to the interior of the bank during the day.

“The exterior window guards will be of solid bronze. The building will be lighted by electricity and gas at night. The plumbing is to be all open, and the building will be heated by the Blower system. The basement will contain the bath-room, engineer’s room, dining room, toilet and coat rooms. In the basement is also the great storage vault, enclosed in a wall two feet two inches thick.

“The bank proper will be grand, and the directors hope to have it the best and most sumptuously arranged one in Albany. The enclosure for the attaches will be in the shape of a horseshoe, the two ends pointing toward Maiden lane. On the south side is a ladies’ reception room, while to the north, if a person has business with higher officials, he ascends the steps leading to the private office. Next, west of this office, is the stenographer’s room, and adjoining is the cashier’s office, the mortgage and insurance clerk’s office, the assistant treasurer’s office, the president’s office and the directors’ room. In the attic there are store rooms and coat rooms.

“The immense dome will be 25 feet in diameter, and will be supported by four columns to be erected for that sole purpose. From the balustrade, beneath the tower to the top of it, the distance is 30 feet. There will be 10 feet of stone work beneath the dome, and the balustrade will be 5 feet 8 inches high. From the sidewalk to the cornice of the main building the distance will be 46 feet 8 inches. Over the main entrance of the bank will be the inscription: ‘Albany Savings Bank, 1820-1897.’ The architect is Henry Ives Cobb, of Chicago.”

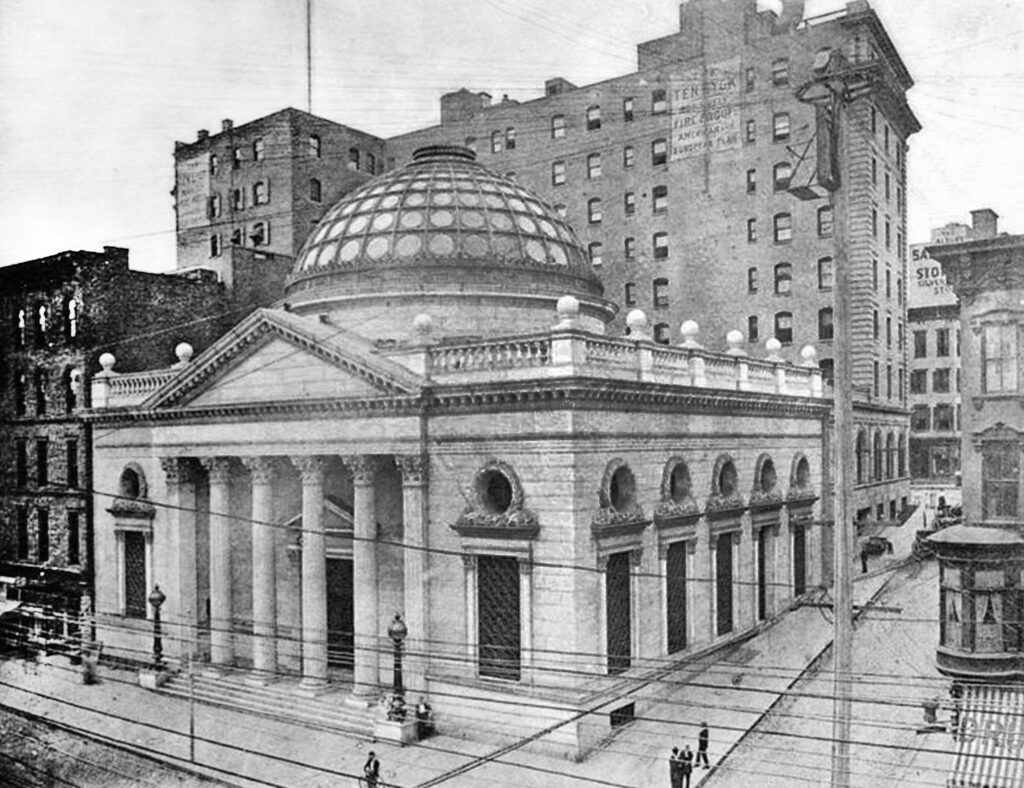

Albany Savings Bank as it appeared early in the 20th century, with the Ten Eyck Hotel behind it on Chapel Street. The now-gone section of Maiden Lane is on the right.

On its opening on April 20, 1899, the Times-Union reported there was an elaborate reception hosted by then president J. Howard King – not in the new bank, but in the rooms of the “Historical society,” presumably the Albany Institute of History and Art. There was much speechifying, including King, Governor Theodore Roosevelt, the president of the state savings bank association (on the mission of savings banks and the aid they rendered the poor), and a long recitation by Mayor T.J. Van Alstyne on the history of the bank, its past officers, and its relation to the city. It also described in detail the columns and windows, the massive bronze doors, the great dome, the five hundred lamps within, the white marble fireplace, the marble clock, and the bank vault “not surpassed in America.”

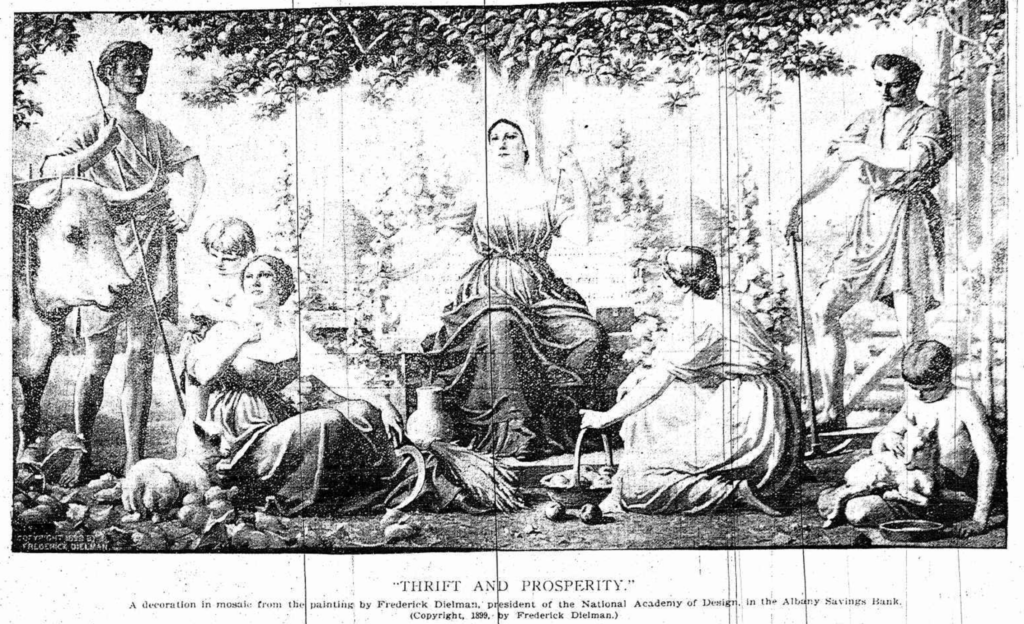

Around 1900, a major mosaic was added to the bank, designed by Frederick Dielman, president of the National Academy of Design, and executed in enamel by Societa Venezia-Murano of Venice. It was 14 feet wide by 7-1/2 feet tall, with enamel pieces no more than a half-inch in dimension. The New York Tribune described the composition in detail and said,

“Mr. Dielman endeavored to make a design which should be a decoration in keeping with the interior of the banking hall, and of such a nature that it would appeal to the sympathies and understanding of the depositors and other frequenters of the bank.”

The article then explained the allegorical figures as representing industry and thrift, emblems of savings, care of animals, and prosperity. It also claimed that “no attempt was made to adhere to the traditions of the older mosaics. This one is in no sense archaic, but modern and realistic in treatment.” (I’d say the most modern part of it has to be the men standing around in Roman togas. That’s very, very modern.)

The Tribune article noted that “Opportunities for future decoration are offered in the great frieze and lunettes, at present flat masses of delicate tint. It is to be hoped that the bank in time will see its way to the enriching of the interior by the filling of these spaces.”

Fate Ties the Bank to the Ten Eyck Hotel

And things went along that way very nicely for a few decades. The bank celebrated its 125th anniversary with a nice commemorative booklet in 1945, filled with historical facts and near-truths about Albany and the bank itself.

Then the urge to modernize hit as part of a wave of “revitalization” that destroyed a whole bunch of nice things downtown.

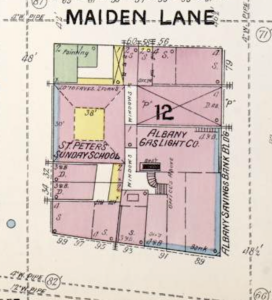

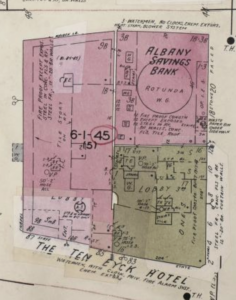

From the Sanborn map of 1934, showing how the Ten Eyck Hotel wrapped around the Albany Savings Bank. North Pearl Street is on the right, State Street on the bottom, Chapel to the left and Maiden Lane on top (north).

Around the same time the bank was being built, in 1897, the Ten Eyck Hotel was built on Chapel Street, between State and Maiden Lane, across from the old Albany Savings Bank building. Around 1916, the Ten Eyck Hotel purchased the Tweddle Building and greatly enlarged the hotel property. Originally owned by the Albany Hotel Corp. (headed by Hiram Rockwell of Glens Falls), the hotel was named for first mayor of Albany Jacob Ten Eyck. United Hotel Corp. owned it from 1912-1945, then Schine Enterprises, a theater owner from Gloversville, ran it until it was sold to the Sheraton Corporation in 1954. In its Sheraton form, it had 400 sleeping rooms and 20 meeting and dining rooms. The Koffman family real estate investment firm of Binghamton acquired it in 1963. At some point it reverted to the Schine name; in 1966 it was reported that Schine had an operating lease from the owners, Harry Koffman and sons of Binghamton.

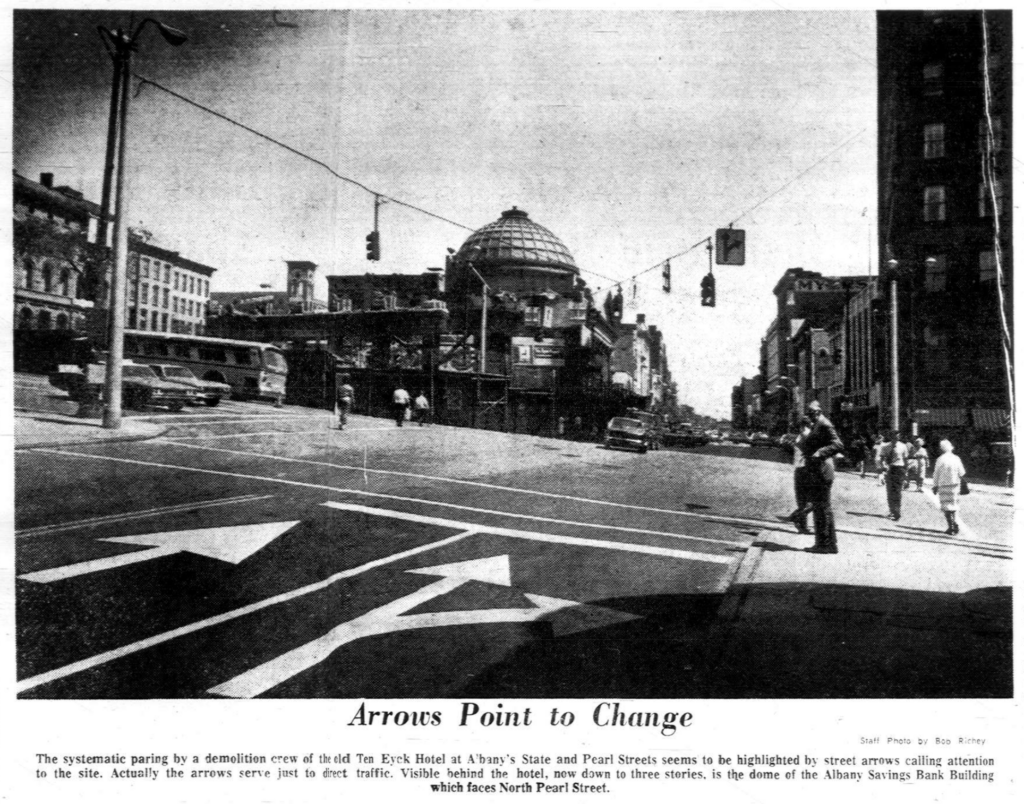

The Ten Eyck Hotel was looking to expand and add meeting and convention space, and in 1964 the Schine group, which operated the hotel, bought one or more properties along State Street and Chapel for a planned expansion. But plans stalled, and at least one of Schine’s acquisitions was foreclosed on in 1965. Bankruptcy proceedings against the Schine family that held the hotel’s operating lease led to its closure. The Schine Ten Eyck was shuttered on Sept. 30, 1968. With the closure of the hotel, other tenants of the building started scattering, including Walgreen’s drug store, which had occupied a space at 2 North Pearl Street since 1948, but now simply left Albany.

While there was some casting about for new uses for the Ten Eyck, and vague plans of combined hotel and office space, demolition was on the table very early on as well. In 1969, it was reported that Albany Savings Bank was “cramped for space and would like to celebrate its 150th anniversary in Albany next June in expanded quarters.”

The State Urban Development Corporation stepped in in 1970, with grand plans for a revitalization that would include a four-block complex including a new hotel with convention facilities, a new home for Albany Savings Bank, an office tower, and underground parking for 1300 vehicles. Governor Nelson Rockefeller at the time said, without any intended irony, “When you start tearing down, building up can’t be far behind.” Once demolition began, it was determined that, in fact, the area was “unsuited for such a parking installation,” as a letter-writer indicated in 1970.

The landmark Cobb building occupied by Albany Savings Bank was doomed in that plan from the start, and in nearly all the plans that followed. With the bank itself anxious for modern new office space, there was simply no one involved in planning the site who was interested in preserving the building. It was given a reprieve when a suitable temporary location for the bank could not be worked out – the old Myers Department Store was one such candidate. It appears what ultimately happened was that the Cobb building was allowed to stand, and the bank to continue its business within, until the new ASB building next door, part of the overall complex, was completed.

But once that was completed, and bank operations moved to the ’70s version of sleek new quarters, it was decided that the old building still had to go. It was torn down in 1976. But the good news is that what took its place was . . . well, hardly a thing. Ten Eyck Park, a very ’70s style concrete and brick public park with some verdant touches, is where the grand old Albany Savings Bank building used to be.

The End of Albany Savings Bank

So Albany Savings Bank, the institution, went on. From 1820 to 1979, the nature of their business barely changed. Then they started acquiring other banks (Heritage Savings in Kingston, Newburgh Savings), and became a federal savings bank (or association). It acquired a few more banks around the region and changed its name to Albank in 1995. And then, inevitably, it was merged into Charter One Bank of Cleveland (not the only time Cleveland and Albany banks were connected – see also Key Bank). Charter One was acquired and merged into was became known as Citizens Bank in 2007. So far, that bank still exists, but there is not a trace of the old Albany Savings Bank. Even Citizens Bank has moved out of that building and down the street.

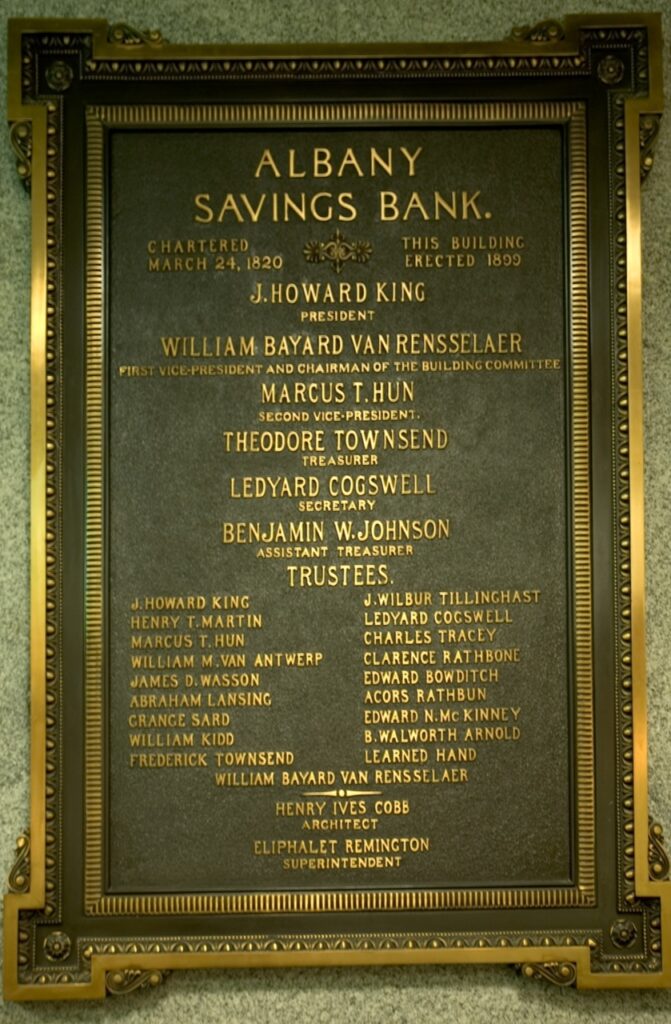

Except: Inside the building, on the first floor near the elevators, there was, and hopefully still is, a large plaque from the Cobb building:

Displacement in the 1890s

As one of Albany’s oldest streets, the space taken up by the Cobb building was, of course, already occupied when the bank sought to build, and numerous business and residents were displaced by that construction. A 1945 history of Albany Savings Bank described the buildings it displaced on Pearl as “a business block of non-descript post-Civil War buildings.” Demolition began in 1896.

According to the 1895 city directory, these were the people who had to find new locations. If there’s an “h.” after their name, that indicates the address was also their home, and these were mixed-use buildings:

14 North Pearl:

Buel C. Andrews, lawyer

Martin Hanlon, tailor

Margaret Roff, milliner

Marvin L. Rowe, dentist, h.

John S. Wolfe, lawyer

Elwood W. Vine sporting goods

16 North Pearl:

George D. Atkins, merchant tailor

18 North Pearl:

Goldring Bros. florists

20 North Pearl:

Philip D.F. Goewey jewelry

Allen Bros. tailors

Marie C. Decker, artist h.

Fred P. Denison, organist

John Rummel, upholsterer

22 North Pearl:

R. Grady & Co. millinery

Henry I. Herschberger, tailor

Jacob I. Herschberger, clerk b.

24 North Pearl:

Bernard Nusbaum, grocer

Miss Ida Snyder, buttonholes, h.

Theo H. Whitbeck, dentist, h.

Albany Savings Bank – We’re Not Albany City Savings Bank

Some historical documents confuse Albany Savings Bank with Albany City Savings Bank. They were not the same. ASB was founded by the last patroon and later led by J. Howard King and other industrial leaders of the city. Albany City Savings Bank was a Corning family institution originally known as Albany City Savings Institution from 1850 until 1921, when it petitioned to change its name to Albany City Savings Bank. That petition was accepted, until it was noticed by the Albany Savings Bank, which thought that there might be some confusion and that, having been in existence under that name since 1820, it had some rights to it. (That there was also an Albany County Savings Bank didn’t help matters.)

A judge agreed: “Is the use of the word ‘City’ sufficiently distinctive? I think not . . . It seems clear to me that in the situation already existing here there is every reason why even persons ordinarily well informed might easily think of the Albany Savings Bank as the Albany City Savings Bank, as distinguished from the Albany County Savings Bank; that ‘Albany City’ and ‘Albany’ are synonymous and indicate the same municipality.”

Not getting their way, the Corning bank went with the moniker “City Savings Bank of Albany.” In 1935, they merged with the folks over at Albany County Savings Bank to become City and County Savings Bank. Its building at 100 State Street still stands.

Leave a Reply