Last time around we talked about aviator Ruth Nichols’s devastating crash at Troy Airport. While nearly everyone in the area would be familiar with Albany’s airport and even Schenectady’s, the airport in Troy seems nearly forgotten about. It had a long history – and despite decades of dreams, it never really grew into anything of significance.

According to a 1960 article in the Troy Record, the airport was dedicated July 18, 1920, as a privately owned “flying field” on what was then called Carroll’s Hill. This was 10 years after Glenn Curtiss had taken off from a farmer’s field on Westerlo/Van Rensselaer Island just south of Albany to claim the $10,000 prize offered for the first flight from Albany to New York City. (Despite reports to the contrary, that was not then Albany’s airport). It was just a few months after a plane owned by vaudeville mind reader Hope Eden became the first to land in Troy, in a field not far from the armory that is now part of RPI.

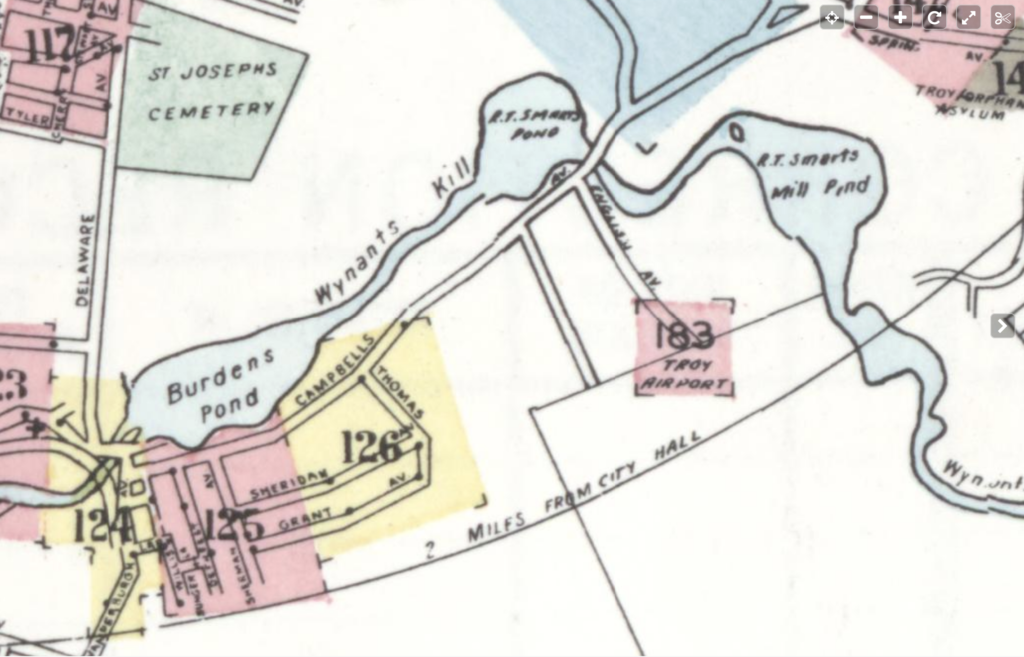

Troy was hardly blessed with flat, open spaces, and the Chamber of Commerce, pushing for air transport, proposed the acquisition of a site on Carroll’s Hill site as “high above the city, comparatively level and in those days considered to need a minimum of preparation.” The field, although privately owned, was publicly dedicated on July 18, 1920, named for “one of Troy’s heroes, Lt. Joseph P. English,” who had served with a British flying squadron and in World War I. (The Knickerbocker Press said he was killed while training in England with the Canadian flying corps; other reports said he was a member of the British Royal Flying Squadron.)

“Several hundred persons witnessed the dedication of Joseph P. English flying field on Carroll’s Hill, South Troy, yesterday afternoon, when the first airplane of the New York Aircraft Corporation, piloted by Ellsworth G. Hayner and James Boyland, Troy aviators, arrived from New York and did numerous circus stunts over the onlookers.”

Although at least two veterans’ groups were named for English, the dedication is the last time we see his name connected with the airfield in any newspaper articles, and it was generally referred to as the Troy Airport or airfield. The field appears to have only been used for local flying instruction; a Troy Record article much later reported that it wasn’t until Sept. 27, 1927, that two students from Harvard College became the first “outside flyers” to land a plane at Carroll’s Hill.

Troy Airport Corporation

It seems very little happened with that earliest iteration of the airport. In 1928, the Troy Airport Corporation was formed, and Edgar H. Buck was named manager. The members of the corporation included John Aird, Charles Aldrich, Edgar Betts, Edgar Buck, William Dauchy and other prominent Troy names. The purposes of the corporation “are to own and operate an airport, operate a taxi service to and from the airport, conduct a restaurant, provide aerial advertising, afford mail, express, freight and passenger service, sell airplanes, repair airplanes and sell oil and gasoline.” Rensselaer County granted the corporation a lease and option on the portion of the “Welfare Home farm” situated south of Campbell Highway. The corporation then purchased 82 acres of the Van Valkenburg farm, which would be the footprint of most of the updated airport, which it said would be called “Troy Aviation Field.”

“A hangar is to be erected . . . A building is to be constructed . . . which will serve as a field postoffice for air mail. A lease of nine acres owned by Rensselaer county just northwest of the field has been given E.H. Buck, on which the two buildings are to be erected. No buildings are to be permitted on the aviation field, but the Van Valkenburgh homestead is to be removed to the land leased from the county. It will provide accommodations for aerial passengers, air pilots and employees of the field and also for administration purposes.”

In May 1928, the Troy Airport Corporation appointed as chief pilot and instructor Lt. Ellsworth Hayner, the first man to fly into Troy, who had served in the US Army Air Reserve Corps. Having enlisted during WWI and received a commission as an instructor, “he is considered an expert in cross country flying and map reading. After the war he became affiliated with the Burch Aircraft Corporation as a commercial pilot. Work on the local flying field is progressing. Two dual control instruction planes have been ordered and it is expected that sessions of the flying school will start in a short time.”

It was also intended that Acme Airways, Inc., formed from the former Troy Flying Service group, would be headquartered at the Troy Airport, as a sales distributor of the Pacer monoplane, manufactured in Perth Amboy, N.J. At least, that’s what was reported; we find no evidence that this actually happened. We did find advertisements in aviation magazines offering pilots’ flying suits, and help in saving money at flying instruction and buying planes. The company was located in the Proctor Building.

Also in 1928, R.P.I. began teaching “the fundamental principles of aviation, newest of the branches of engineering,” at a senior and post-graduate level. “The course will come under the general head of mechanical engineering, and will be concerned with the fundamental principles of flying, motor construction, and the like. There will be no actual flying connected with it,” according to Aero Digest. It was expected that more than 100 students would take the course. It was also noted that “a group of students have formed the Rensselaer Aeronautical Club of R.P.I.”

In 1929, while teaching a student how to recover from a tailspin, Hayner died in a crash of a Swallow biplane along the Wynantskill/Albia line, near Smith’s hotel. His widow said that after they were married in 1925, he had given up flying at her request, “but I could see that he wasn’t happy at any other work. It wasn’t until a year ago that he returned to the business he loved so well and I let him go.” Soon after, there was a recommendation to change the name of the airport in his honor. If that happened, the name was never used – it remained Troy Airport.

As aviation grew, there were repeated plans to do something more with the airport, but the onset of the Great Depression meant few of them came to fruition. A planned 1930 expansion, with new hangars and floodlights, never happened. In 1931, Buck announced that he intended to take over and develop the Troy Airport, which doesn’t appear to have happened. The property went into foreclosure in 1933, at which time the Troy Times reported that the airport had been “in a state of disuse for several years.”

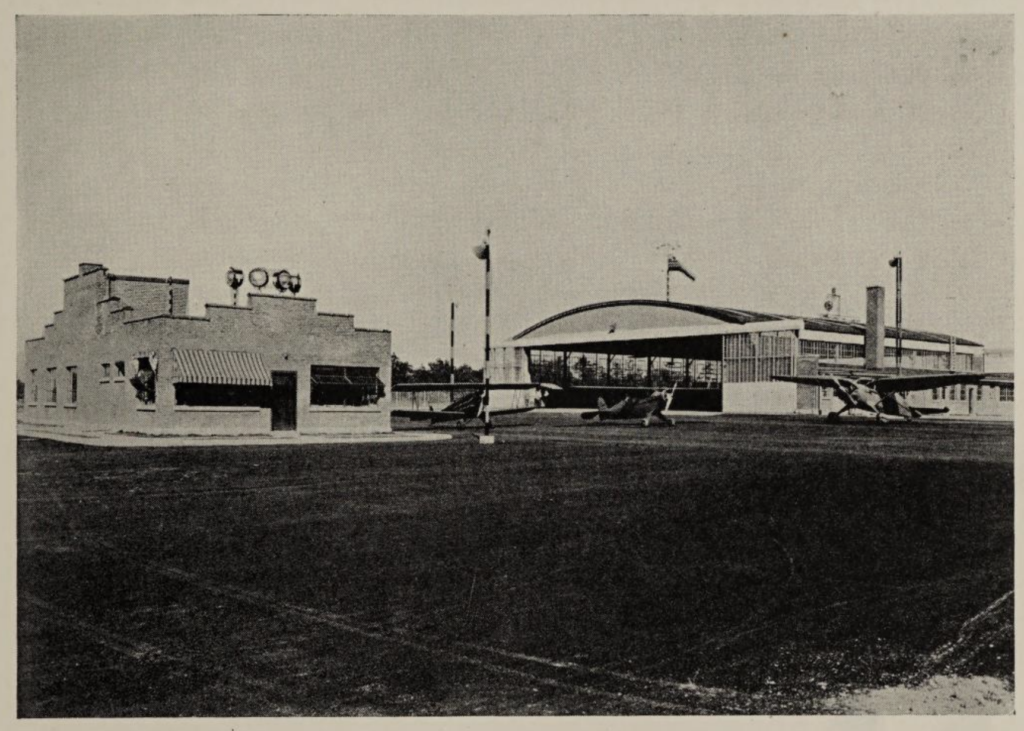

The airport was auctioned off to a new corporation, Troy Aviation Field, Inc., in 1934. That company then leased the airport to the city of Troy for $10 a year. In part, that appears to have been to allow municipal money to be spent on improving the airport. “This will enable grading of the field as a CWA [Civil Works Administration] project, whereas it could not have been done under private ownership . . . Mr. [Robert] Aldrich will have his office at City Hall and later at the Airport where construction is in progress on the administration building and hangar.” Somewhere in that time period, the City of Troy became the owner of the property.

Troy owns an airport

Troy’s Mayor Cornelius Burns was an avid booster of the airport – municipal airports were, in fact, all the rage – and participated along with other officials in new dedication ceremonies and an air show held Oct. 27, 1934. There was an air parade of 25 planes, a demonstration of stunt flying by Harold Bowen of Elmira, a demonstration of the Lanier Vacuplane, “smallest airplane in the world,” a demonstration of how 600-foot advertising banners were taken into the air for advertising, and then a flying exhibition by the 27th Division Air Squadron. The crowds were quite large.

In February 1935, former Albany aviator Robert Aldrich was formally appointed director of the Troy Airport, “after the position was created by the Troy Board of Estimate and Apportionment with a salary of $3,000 a year. The board placed the job in the municipal bureau of engineering in the Department of Public Works.” Now the airport director was on the city payroll.

“In 1936 a corporation to control the air field was organized and the place was rededicated as a city airport on Oct. 27, 1937, with Robert Aldrich as the first director.” In 1936 it was reported that there were 12-14 privately owned planes based there, and Aldrich said a second hanger may soon be necessary.

In 1939, the entrance roads to the Troy airport were named in honor of the two flyers, Hayner Avenue and English Avenue; it’s not clear when those designations were dropped but they don’t exist today – they are Donegal and Colleen, respectively.

With application to the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for a new drainage and grading project in mid 1939, it was reported that the area of the airport would have doubled within a year and the average length of the runways extended 43 percent. The runways would have the following lengths: north-south, 2700 feet; northwest-southeast, 2950 feet, northeast-southwest, 2500 feet, and east-west, 2250 feet. The airport also had new two-way radio facilities, “one of the finest shops in the state for airplane repairs, both flying and ground schools and 22 planes regularly in the big hangar.”

Wartime

In 1940, as war broke out in Europe, the federal Civil Aeronautics Authority, under a Presidential proclamation, was looking to massively expand pilot training – seeking to train 50,000 civilian aviators in the course of a year.

“The 50,000 trainees will be young men between 18 and 25 years of age, and will be drawn from three classifications – those from the 435 educational institutions at which the program is now operating, such as Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute now using the Troy Airport, and as many more as wish to start the training; a ‘large group of citizens’ who now have licenses but who have allowed them to lapse, and men in the proper age category but not in college who desire to make themselves available for military service. it is proposed by the CAA that flying schools, such as that at the Troy Airport, which ordinarily would close for the summer during the school recess, will be continued through the summer months this year. With defense plans calling ultimately for an air force of 50,000 planes, it will be necessary to have a personnel of some 200,000 trained flyers and groundmen.”

It’s interesting if that means the Troy airport closed in the summers; that could indicate that the bulk of its flying students already came from R.P.I. The staff of the airport then consisted of Robert Aldrich, pilot Robert Reno, two mechanics, an apprentice, a janitor and two night men.

During the war, R.P.I. and the Troy Airport had a significant role. In September 1942, it was reported that the Navy Department had sent its second group of 50 V-5 aviation cadets to Troy “to take a ground school course at R.P.I. and to receive actual flying instruction at the Troy Airport.” It was an eight-week program, with students spending half their day in R.P.I. classrooms and half at Troy Airport. The Navy’s relationship with R.P.I. grew tremendously; in 1943, Lt. Comdr. Daniel Brimm of the Training Division, Bureau of Aeronautics, said the Navy intended to use all facilities at R.P.I., and said “The Navy thinks Troy Airport and Troy Flyers, Inc. are doing a swell job, outstanding in the CAA program.” He said the Naval Flight Preparatory School at R.P.I. “stands at the top of the list in marks.”

By then, Robert Aldrich had left – in 1940, he was appointed as airport engineer for American Airlines at Laguardia Field in New York City in 1940; the Times Record called it a shock, and credited all success of the airport to him. But the CAA program continued through the war under Troy Flyers, Inc., headed by Robert H. Reno of East Greenbush, who had “left his coal and ice business in Rensselaer twenty years ago to get into something with a ‘future’”.

In August, 1944, the Times Record reported that Troy Flyers school had completed its federal government contracts, “and the local air lanes are again cleared for civilians.” Reno said that since the start of the civilian pilot programs, “the Troy Airport flying school has trained 3,225 government students and has been able to accommodate 2,000 private students as well. Today, there are 136 students on the rolls.” That article was focused on the growing number of women learning to fly, and noted that “many of the women who have learned to fly at the Troy Airport are playing an important war role, serving in the WAAF as weather observers or ferrying planes . . . An outstanding woman flyer is Barbara Gibbee Jayne, who is making test flights as soon as completed planes leave the assembly line at one of the major plane factories.” (The WAAF was the British Women’s Auxiliary Air Force.)

Post-war malaise

Following the war, in Sept. 1945, Troy Flyers Inc. lost a bid to operate the airport; instead it was awarded to “Airport Operators of Troy, N.Y., Inc.,” a company formed by Hoosick Falls native and NYC attorney Walter F. Doyle and “recently discharged sailor” Thomas J. Manning of Albany. Vice President J. Norman Southlea “will be the technical man in the operation.” Doyle said that he and Manning “had a few dollars to invest and both being from this section and knowing of the possibilities of the Troy Airport, we decided to invest it there.” He added that “we are sure that the Troy Airport is better located than either the Albany or Schenectady airports and that in the past its possibilities have not been properly developed.”

Southlea, who was reported to have been associated with Royal Air Force training in the US and managing an airport near Poughkeepsie, said “We don’t ever expect to have the Chicago and New York planes landing here but there is no reason why the Troy Airport should not be otherwise tremendously active in the commercial field.” He expected a great deal of charter work, and said they would be running a flying course. The city of Troy had been losing $5000 a year on the operation; two years later they called the lease advantageous to the city. Under the new arrangement, the city was paying only the salary of an inspector. However, it was certainly not making money on the lease.

As before, these plans to expand, to attract new business, and to grow the airport’s operations, came to nothing. Private flyers continued to keep their planes there. In the early 1950s, the airport continued to be in use for flight school and college competitions – for example, a meet in 1951 brought together student flyers from R.P.I., Syracuse University and Siena College in cross-country and “bomb” dropping competitions (the bomb was a bag of lime). Six of the twelve flyers competing had served in the armed forces as pilots.

Redevelopment plans

Around 1953, the Hudson Valley Technical Institute (HVTI) was formed, a community college under the State University of New York. Like several other community colleges we’re aware of, HVTI began its life in a secondhand building – the former Earl & Wilson shirt, collar and cuff factory, a four-story mill building at Broadway and Seventh that had previously been used as a veterans vocational school. HVTI grew rapidly – from 88 students at the start to 650 in 1960 – and it soon needed to find a new site. As early as 1954, there was talk of having Troy donate a portion (or more) of the airport property for a new campus. That ran into opposition in the city council and from those who owned planes at the airport, slowing things down for several years. HVTI – which became HVCC – instead found a home close by, at the former Williams Farm, and opened there in 1960.

But that didn’t secure the airport’s future as an airport. By then it was clear that it was never going to become a transportation hub – Albany had long since claimed that distinction, and Troy’s runways were never updated after the WPA projects – and the city began looking for better uses for the land. In April 1960, the city notified Airport Operators of Troy, Inc., which had held the lease since 1944 and were paying $250 a year for the privilege, that the city would take possession of the land and facilities. The city intended to move quickly to offer the land, about 150 acres considered buildable, for industrial purposes. Airport director William McGrath said there were no plans once they lost the field. “We have no place to go.” Twenty-two planes, mostly locally owned, were housed at the airport. “The value of the field for any purposes will be enhanced under the state arterial program, with a highway artery and a feeder road running close to the site,” the Times Record wrote. Fortunately, as it turned out, Troy was undisturbed by interstate arterials, but at the time that was part of the plan.

In March 1961, the Troy Industrial Park was formally created. But private plane owners initiated litigation that tied up any further development there, and for several years, Airport Operators continued to operate even though its lease had been terminated.

In 1964 the Times Record ran an editorial titled “Get On With It,” applauding a decision by the city asserting its right to possess the property and evict Airport Operators, hopefully ending “thirty years of futile dreams that have caused the Troy Airport to become a white elephant.” The Times Record said that the land “cannot continue to benefit an exclusive and tiny group at the expense of all the citizens of Troy,” and that the acres offered Troy’s only extensive industrial development site that wouldn’t require demolition of old structures.

A group called the Troy Airpark Development Committee tried to put together a plan that could combine a new 4,000 foot airstrip with surrounding industrial development. That didn’t come to fruition, and the City finally forced the closure of the airport effective June 1, 1964. The last flight out of the airport, on May 31, unfortunately ended in the death of a 22-year-old pilot from RPI, Norman Wainer, whose Piper Colt seems to have lost engine power, crashing and burning on the airport property.

With the airfield finally closed, Troy sought to form an industrial authority to develop the site – but that took more than two years to pass the State Legislature, initially drawing a veto from Governor Rockefeller out of concern they would draw industry from other cities in the state. Ultimately the Troy Industrial Authority was created in 1967, with board members chosen by the City Council. But reality continued to set in, and with little significant interest in the airport site, the TIA by 1972 was shifting its interest to South Troy, where it thought it could attract major industry to the old Republic Steel property. It was recommended that the airport site be rezoned for housing.

In the meantime, around 1969 Troy had faced a garbage disposal crisis, and hurriedly authorized the use of some of the airport – primarily a ravine at the remote end of the site – for a short-term landfill. The result was corruption charges, lawsuits, and more. The landfill site did not, however, overly complicate plans to turn the rest of the property over for residential development, and by 1973, a development was approved and new homes called “Emerald Greens” were being offered starting at $24,000.

The site is now primarily homes and apartments, along with a local technical school and a handful of small light industrial buildings. The names of Hayner and English are long gone from the streets. A city-owned solar array sits atop a portion of the site. No evidence of the airport remains.

Leave a Reply