The 39th in our series of Albany Bicentennial tablets was one that simply provided the name and former name of Norton Street:

Tablet No. 39—Norton Street

Bronze tablet, 7×16 inches, north side of Beaver block. Inscription

“ Norton Street, formerly Store Lane.”

Despite the Bicentennial Committee’s intent to place this on the Beaver Block, The Argus reported that this was actually placed on the south wall of the building on the northeast corner of Norton and South Pearl streets, not the Beaver Block. As we’ll see that means it was affixed to the Bensen Building. There is no building there anymore; it’s a small parking lot surrounded by a low wall on the back end of the faceless tower at 80 State Street, with no evidence of the Norton Street marker.

As with our last few markers, the Bicentennial committee seemed to just want to mark random streets, without providing any kind of context or justification for which streets they marked and which they didn’t. Norton Street, once considered worthy of a permanent marker, now doesn’t have a single front door that opens on it – it’s essentially an alley. (And we found no indication of when its name was changed to Norton, or why.)

At the time of the Albany charter bicentennial, in 1886, Norton would have been a busy street in the center of downtown Albany, albeit one that still served more for warehousing than retail business. Today, someone coming from Green Street could easily confuse Norton Street with a private driveway, given that it runs under the bank building numbered as 60 State Street.

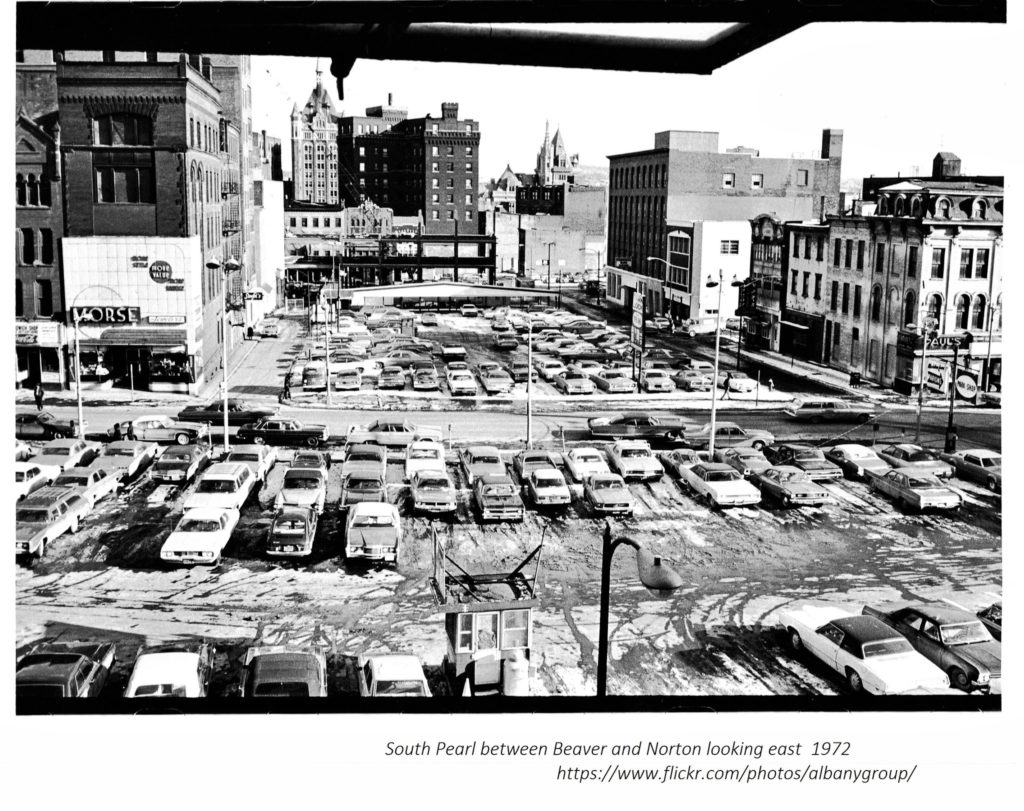

In 1796, the second building housing the First Presbyterian Church was sited at the corner of Norton and South Pearl (covering the block to Beaver). The church remained there through 1850, after which it housed the Congregational Society, and then was replaced by the Beaver Block (or Beaver Building), which housed many businesses and served as a union hall as well. The Beaver Block was gone by 1972, when it appears as the site of a parking lot.

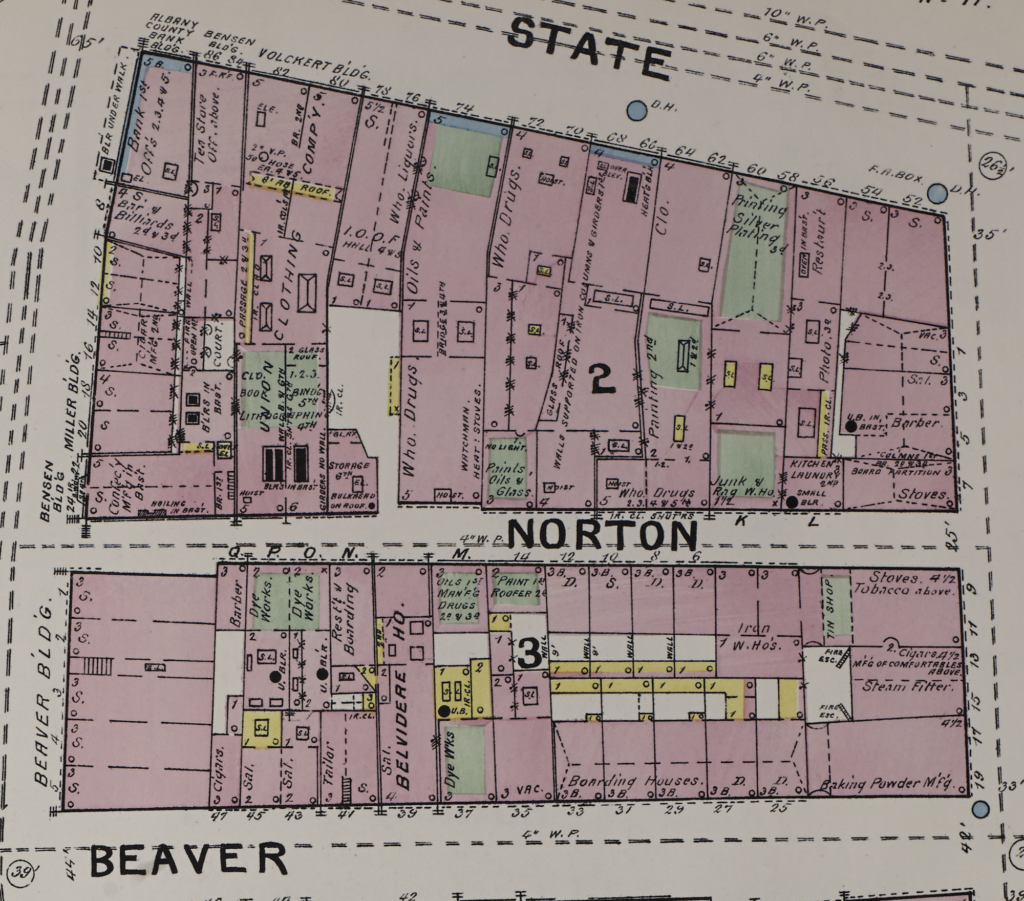

In 1876 (close enough to the Bicentennial marker’s placement), Norton was partly an alley, but also had a number of buildings fronting on it. This map shows the names of the owners of the buildings, not necessarily the businesses that were contained therein. As can be seen, Thomas Olcott, of the Arbor Hill and banking Olcotts, owned a chunk of the buildings along Norton (as well as Beaver).

Even looking at the 1892 Sanborn map, it was clear that Norton was more a service street than anything else. On the north side of the street, it would appear there were a handful of businesses that opened onto the street, but only a handful. Some of the buildings marked “Paints, Oils & Glass” and “Who. Drugs” are the back of the Douw H. Fonda Drug Co. at 70 and 72 State; McClure, Walker & Gibson was in the same business at 74 State. Perhaps the “Junk and Rag [Warehouse]” opened onto Norton, but it’s not clear.

On the south side, there were a number of doors that faced Norton, starting in from South Pearl with a barber just behind the Beaver Building (Martin J. Ketzer, 26 Norton), and a dye works (W.D. McFarlane, 24 Norton, who also had locations at 80 Hudson and 50 Orange). There’s a restaurant that may be part of the Belvedere House hotel, more paint, oil and drug manufacturing (probably an extension of Fonda’s very spread-out business), and then a series of dwellings (marked with a ‘D’ on the map; ‘S’ stands for store). Toward Green, there’s a warehouse, and then a tin shop that is probably part of Charles Baker’s tinsmithing and stove dealership at 18 Green.

Aaron Burr

There’s no question, the most famous denizen of Norton Street ever – though he worked there, rather than residing there – was Aaron Burr.

So, about Aaron Burr. Despite history’s vilification of Aaron Burr (seems like there were two people in that duel), he was a complex character with some solid Albany ties. Burr was anti-slavery (unlike some members of the dueling party who married into slave-holding families) and, believing in equality for women, introduced an early bill allowing women to vote.

According to a summary by the Albany Institute of History and Art, Burr came to Albany in 1781, seeking a waiver of a required three year legal apprenticeship due to his military service. His petition was accepted in January 1782, he was admitted to the bar, and he set up a law office on Norton Street. He married Theodosia Prevost on July 2 of that year and set up house in Albany, where the Fort Orange Club is now located. They moved to New York City in late 1783, after the end of the war, but he frequently traveled back to Albany. He served in the Assembly in the 1784-85 term. He was the state’s attorney general from 1789-1791, which overlapped with the beginning of his term as United States Senator. After serving as Jefferson’s first vice president and being dropped from the ticket for a second term, Burr returned to run for governor of New York, losing to Morgan Lewis. He felt that Hamilton and his cohort had smeared him, and so on and so forth. (New York Almanack has a nice summary of the Albany ties of Burr and Hamilton.)

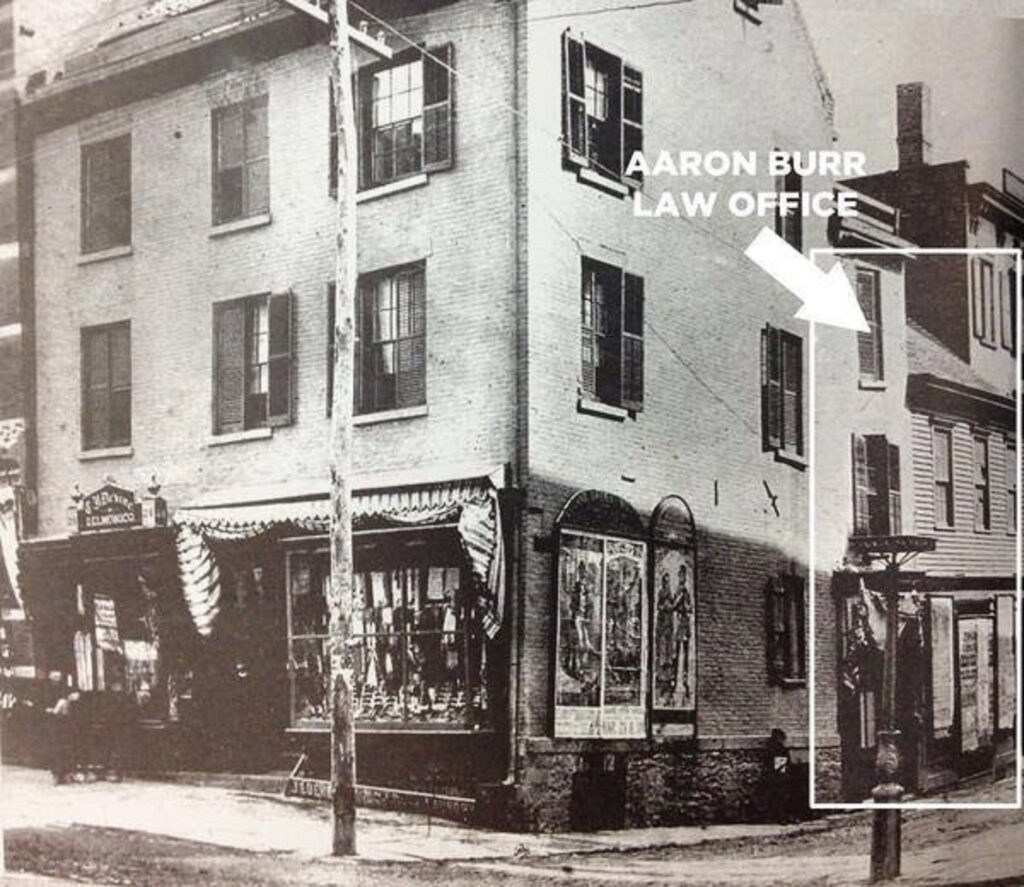

Demolition, because it’s Albany

The building where Burr practiced law was well known and recognized, one lot in from 24 South Pearl on Norton Street on the north side. In 1887, Albert V. Bensen, tea seller, paste-maker, banker and more, chose to tear down the buildings on that corner to put up a new five-story Bensen Building. The Argus lamented the loss, writing several articles prior to and after the demolitions, calling 24 South Pearl “the oldest building in the city,” one at which General Schuyler was supposed to have lived (we covered that with Bicentennial Tablet No. 15), and that the Norton street building was the “very last of its kind that is roofed with the old red tile of the olden time. Now the question arises. How can these relics of our colonial period be saved or utilized?” It lamented the loss of the Stadt Huys (“Were it standing to-day it would be as sacred to the people of Albany as Faneuil hall is to Bostonians, or Independence hall to Philadelphians”) and the old Capitol, “which should have been allowed to remain to show in a measure our advancement as a State and which would not have obscured the greatness and magnificence of the new Capitol any more than a spot interferes with the brilliancy of the sun.”

Under the later headline “Another Landmark Doomed,” The Argus this time said that the building on South Pearl was the only building remaining with a Dutch tile roof (though a tile roof on Norton Street does appear to be visible in the photograph above).

“It was built in 1735, the tiling and brick being brought from Holland, and the house being the only one in the city having a genuine tile roof. The tiling has been purchased by a gentleman who intends erecting a house in the Helderbergs.

“The adjoining house on Norton street, once the residence [sic] of Aaron Burr will be demolished first, to make room for the new five story building which Mr. A. V. Benson [sic] will erect on these sites.”

A later article, after the demolition, said that:

“…both are among the few brick buildings in the city that were built before the revolutionary war and have remained until the present year, the Norton street house having been erected by Anthony Van Schaick, who died before that era, as is shown by a deed drawn in 1777 that it was then owned by his heirs.”

The Bensen Building stood on the corner of South Pearl and Norton until about 1984, when the new and widely derided glass tower known only as 80 State Street (many called it the IBM Building, based on their tenancy) was constructed. (Bensen’s properties ran all the way to State, including the Waldorf building, causing a bit of confusion with regard to the “Bensen Building”).

The Lock Hospital

Once upon a time, or at least in 1830, 3 Norton Street was the location of the Albany Lock Hospital, which was operated under the direction of Gen. George Cooke, M.D., LL.D. The credits of Dr. Cooke, as laid out in his self-published practical treatise on genital maladies in 1852, were given as follows:

“Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons; corresponding vaccinator of the National Vaccine Institution, under the sanction and authority of the British Government, London; Chancellor of the University, and President of the Medical Department of the College of Ripley, in the United States of America; formerly assistant surgeon in the Royal Navy- British and foreign hospital staff, and the Hon. East India Company’s service; the only army and navy surgeon living in America at the present day, who has ever visited the hospitals of England, France, Belgium, Germany, Australia and South America; and for the last twenty-two years, medical and surgical referee in Albany, in clinical practice, chronic complaints, &c.,&c. &c.” Yes, he wrote “&c.” three times.

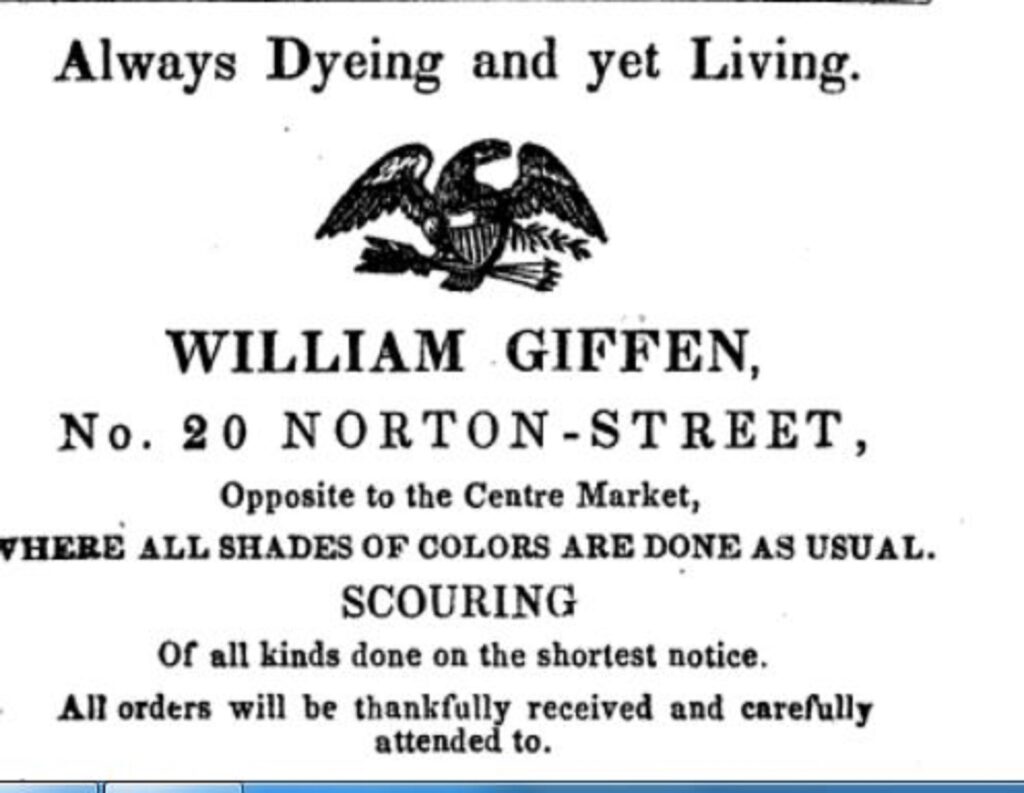

A “lock hospital” is a most unfortunate name in a number of ways. The phrase originated from the horrific practice of locking up (and physically restraining) people suffering from leprosy, a disease that at the time Cooke was writing was still not understood as bacterial in nature – that wouldn’t come until 1873. But the phrase was soon applied to the forced treatment of venereal diseases in the British colonies, in both civil and military facilities that treated, with whatever crude methods were available, what were then called venereal diseases. It’s an ugly history, but the fact remains that port cities throughout the world saw the establishment of “lock hospitals,” which no longer locked in their patients and which were often the only source of any medical assistance for someone suffering from sexually transmitted diseases at the time. Dr. Cooke advertised that he provided “the prevention and removal of all diseases requiring professional secrecy, without mercury,” with office hours from 6 AM to 10 PM every day, including Sundays throughout the year.

The location on Norton Street was likely no accident – convenient to the river and canal, and likely a low-rent district even in the 1830s. Cooke himself wrote:

“Norton-street certainly is not a very aristocratic spot, but is central–its buildings are occupied by respectable families –and, as regards his offices, they are large, convenient, and easy of access; in size, the whole upper part of the building being fitted up and devoted to the preparation, &c., of his medicines.”

How Cooke came to settle in Albany he doesn’t seem to explain, but his passion for treating the afflicted and his outrage against other pretenders to cure come through strong in his treatise.

“If you are afflicted, delay not an instant after the first symptoms of disease appear to apply to a skilful physician. Let no false delicacy, no fear of expense, deter you; for you need not hesitate to expose every secret to one whose lot it unfortunately is, daily to witness the inroads made upon health by sensual indulgence. If you have the means, you are amply remunerated by the best professional advice; and should your circumstances be limited, this will always be considered by a medical man of honor.”

He fills pages with tributes to his treatment and his willingness to consider ability to pay.

Let’s be clear: willingness to treat such patients doesn’t mean his treatments were in any way effective. It wasn’t until 1879 that the bacteria that causes gonorrhea was discovered; in 1905, the microbe that causes syphilis was discovered. An arsenic-based treatment for syphilis was developed around 1910. Prior to that, nearly all treatment was either snake oil or poison (usually mercury, arsenic or sulphur).

Cooke was well-regarded, not least by himself. As he reports:

“The Young Men’s Association, representing the citizens of Albany . . . as a public demonstration of their respect for, and gratitude to Gen. Cooke, their venerable patron, some time since made an honorable appropriation to obtain a Life-size Medallion Bust of that gentleman, and have placed it in their Library and Reading room. It is wrought of pure white marble, and secured in a handsome and richly carved case superbly mounted – a work of art which reflects a just meed of praise to its sculptor, as well as manifests a suitable testimonial of the feelings of thousands of persons of whom their society is in part composed, who value Gen. Cooke as a well-tried, true and faithful friend.”

That bust was made by Erastus Dow Palmer, Albany’s famous sculptor. According to Peter Hess at New York Almanack, the bust now stands atop Cooke’s grave at Albany Rural Cemetery.

Norton Street today

Just for the record, we grabbed some screen shots of the current StreetView of Norton Avenue, which turned up an interesting and odd little piece of cast-away signage:

Leave a Reply