The Albany Bicentennial Committee chose to honor Academy Park with a bicentennial plaque – interesting in that it is the only one that celebrates a public space (not counting particular streets that were commemorated, which we’ll get to). Washington Park didn’t get such a mention, and Lincoln Park didn’t exist yet. But news accounts of the day make it clear that Academy was never considered a central gathering place for the city’s residents, it was just a small neighborhood park, and not always the best kept one. The Committee provided this description:

Tablet No. 31—Academy Park

Bronze tablet, 11×23 inches, inserted in granite block, similar to No. 7, placed in Academy Park. Inscription :

“On this Ground the Constitution of the United States was Ratified in 1788. In 1856 the Dedicatory Ceremonies of the Dudley Observatory and in 1864 the Great Army Relief Bazaar were held Here.”

The marker itself, ultimately cast with different words than those recorded above, was still in existence when The Argus cataloged them in 1914. And it was still there in 2009 when Flickr user Wally Gobetz photographed it; we use it here under his Creative Commons license. We presume the tablet is still there but forgot to look for it when last we were in town.

A century later, another, much more noticeable marker was placed for the 1986 tricentennial, which says:

“ACADEMY PARK – Established in 1882. A hill on the site required the removal of 10,000 loads of sand and clay, filling a gulley on the north side of Elk Street where present houses were built.”

That marker, by the way, is all kinds of wrong. The park was established decades before that, the houses were there well before 1882, and while there was a general revamping of the park around that time, including some leveling of the land, it wasn’t nearly as dramatic as that marker makes it sound.

Academy Park

The Albany Academy building, one of the few buildings remaining to give evidence of Philip Hooker’s once vast influence on the city’s look, had its cornerstone laid in 1815, and the building was completed in 1817.

Shortly thereafter, in 1819, Academy Park was “excavated to use soil in grading Lydius street [Madison Avenue], causing a pond in the depression,” according to Cuyler Reynolds’s “Albany Chronicles.”

Horatio Gates Spafford’s “Description of Albany in 1823” (contained within Joel Munsell’s “Annals of Albany,” Volume 1), mentions Academy Park several times in succession:

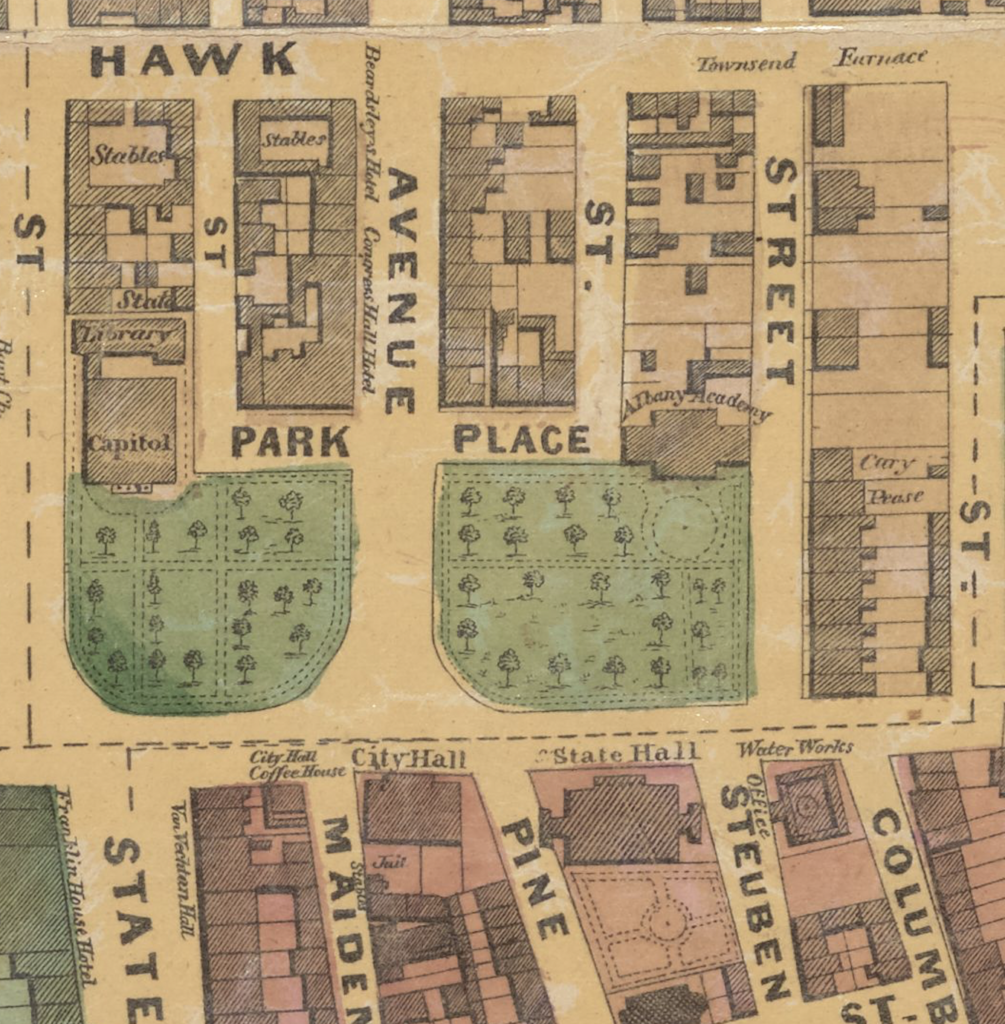

“The Public Square, on the southwest of which stands the Capitol [the old Capitol], has recently been laid out in the style of a Park, surrounded by a handsome fence, levelled, laid out into walks and avenues, and planted with shrubbery and trees, the latter of very diminutive size. Facing this on the west is Gregory’s Row, a handsome range of well-finished brick buildings, extending also around the corner and up the south side of Washington street, on the north side of which there are some good buildings, and extending northward, facing the Academy Park. Washington street [avenue], across the Public Square, seems to divide it into two parks, Capitol Park and Academy Park, separately enclosed, the latter laid out and planted in the same style as the former. On the northwest corner of the Public Square, opposite the Capitol, north of Washington street, stands the Albany Academy, a large and elegant pile of masonry, faced with the red sandstone of Nyac [sic], the same as that used in the Capitol.”

So by 1823, there was a fenced space called Academy Park, with Capitol Park to its south (recall that the Capitol then was in a different location, closer to the corner of State and Elk), and “some good buildings” along Washington, buildings across Eagle that were long since taken for the State Hall, and buildings on Elk that date to the 1820s, ’30s and ’40s.

As early as 1831, there was a local subscription (fundraising) campaign to grade and re-fence Academy Park. A committee raised $3200 from individuals and paid it to the city treasury, and the superintendent of the parks district was charged with grading the park and enclosing it with an iron fence. After the new fence was in place, the Common Council considered resolutions that would have renamed Academy Park as City Park, and Capitol Park as State Park, because creative naming was really not the Council’s thing. Happily, that did not come to pass.

The fence did. Reynolds wrote it was “about 9 feet high, set in a coping of marble blocks about one foot high, with gates at the four sides.” Gutters from Lafayette street crossed “near the centre as a stream in wet weather.”

We had never before heard of “Gregory’s Row,” as mentioned above, but it turns out that it was indeed a thing. A 1952 article on the city’s history in the Times-Union connected it to Matthew Gregory, who, it said,

“…retired as boniface of Tontine’s Coffee House and went into real estate, building a row of houses on Park place (which ran through Capitol Park). This development was ‘Gregory’s Row.’ He leased one of the houses to Leverett Cruttenden for a hotel, opened in 1814 as the Park Place House. Cruttenden waxed successful, took over more of ‘Gregory’s Row,’ and merged the houses into Congress Hall, long the main hotel of Albany.”

The newspaper further noted that Congress Hall (where Lafayette stayed on his 1825 tour) was bought to be torn down to make room for the new Capitol in 1867, but it was not immediately needed. After it had sat vacant for a year, restaurateur Adam Blake leased it from the state and reopened it, operating Congress Hall until 1878 before he moved on to the Kenmore. Some reports indicate he bought up all of Gregory’s Row – but that may only be the buildings that were amalgamated into Congress Hall.

The Constitution

The original language of the marker, as approved and printed by the Bicentennial Committee, said that the U.S. Constitution was ratified “upon this ground” in 1788, which was patently untrue. New York was the 11th state to ratify the Constitution, doing so at a Constitutional Convention held in Poughkeepsie on July 26, 1788. The Court House in Poughkeepsie was the capital of New York at the time. Prior to its permanent settling at Albany in 1797, the state’s capital moved around from year to year, with the Legislature meeting in Albany, Kingston, Poughkeepsie, New York City, even Hurley for a hot minute in 1777.

But between the time of its approval and its casting, the language of the marker was revised to read, “Upon this ground the ratification of the Constitution of the United States was celebrated in 1788.” Why that would even be is unclear – what became Academy Park was pretty far from the center of Albany at that time. It’s not impossible, just seemingly unlikely.

Dudley Observatory Dedication

It is true that an estimated 5000 people attended the dedication of the Dudley Observatory under tents at Academy Park, which was a pretty long way from the observatory. The tenth meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) was held in the Capitol (again, the old Capitol) to celebrate the dedication of the observatory. To say that the observatory itself was unfinished would be an exercise in understatement. None of the instruments had been received by the time of the inaugural ceremonies on August 28, 1856, and without the instruments in place, the walls of the building had to remain unfinished. Two years later, little had changed. (We’ve written about it before.)

The Annals of the Dudley Observatory provided some more detail. While the AAAS meeting in Albany was indeed a very big deal, the dedication of the observatory rates barely a mention in the Association’s proceedings from that meeting. Scientific papers of every conceivable type were presented during the days of meetings in the Capitol. After the presentations were concluded, there were ceremonies for the dedication of the State Geological Hall, on August 27, which featured not only respected scientists like Louis Agassiz and James Hall, but former president Millard Fillmore. Following that dedication, the Association “adjourned to a reception held that evening at Mrs. Dudley’s home.” Blandina Dudley was the financial force behind the observatory. As the Annals report:

The observatory was to be dedicated the next day. Despite all the grand plans, the appearance of the Dudley Observatory in August of 1856 was not one that inspired confidence. The trustees later described their embarrassment during the inauguration ceremonies: “The Observatory itself had the appearance of a ruin. The walls of both wings were open to receive the piers and cap-stones, and to permit the workings of the ‘Ingenious Crane,’ . . . instead of leading their distinguished visitors up the hill, to spread before them the glories of the model instruments, the efforts of the Trustees were directed toward keeping them within the limits of the Capitol.”

The Great Army Relief Bazaar

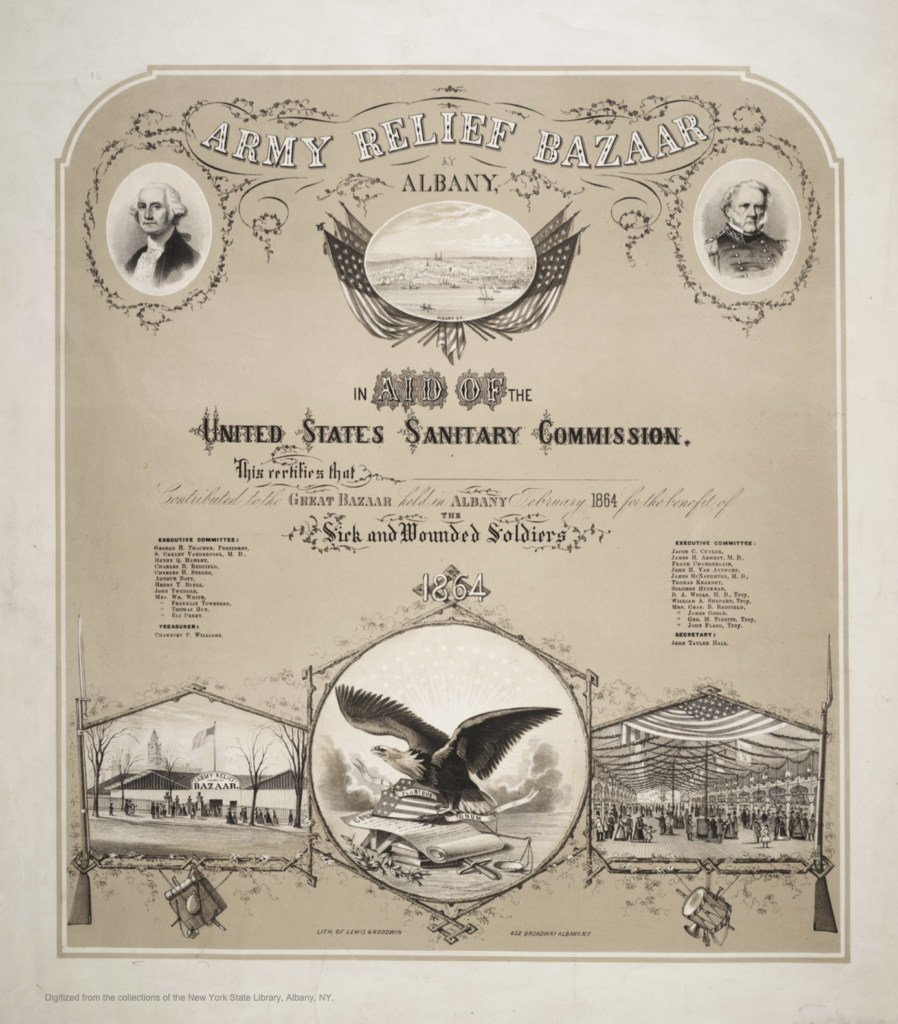

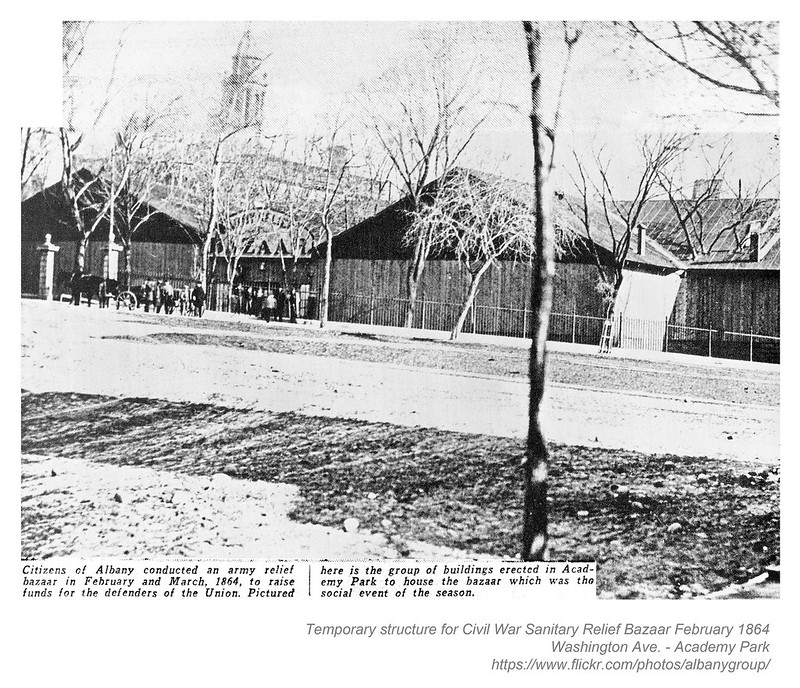

The Great Army Relief Bazaar, however, was a real thing that actually happened at this site, and one worthy of commemoration. It was also known as The Great Sanitary Bazaar, and the Bicentennial Committee chairman, former mayor A. Bleecker Banks, included an extensive description of it in his “Albany Bicentennial Historical Memoirs.”

In the endeavors which were made to provide for the families of soldiers needing assistance, a committee was appointed to raise a fund called the “Citizens’ Military Relief Fund,” and this was soon supplemented by the “Ladies’ Army Relief Association of Albany,” which was organized in November, 1861, to co-operate with the United States Sanity Commission in aid of the sick and wounded, the first president of such association being the wife of Governor Morgan, and its first executive committee being composed of the leading ladies of the city.

It’s a shame women didn’t have names in those days.

“In the months of February and March, 1864, there was held in the city, the great Sanitary Fair, in a beautiful building erected for this special purpose in the Academy park, it being designated as “The Army Relief Bazaar,” and the credit for the organization of which belonged to the patriotic ladies of the Army Relief Association. On February 22, 1864, the fair was inaugurated amid the greatest enthusiasm, before an immense audience and under brilliant auspices, an eloquent and appropriate introductory address being delivered by the president of the fair, ex-Mayor George H. Thacher, the father of the present Mayor of this city . . . .”

It does go on. A nice summary of “sanitary fairs” is available here. During its run from February 22 through March 30, 1864, this one raised about $100,000 for medical relief for soldiers on the battlefields through sales, concessions, and lotteries.

Reconstruction

By about 1880, when one Thomas H. Fehr was arrested for stealing bars from the Academy Park fence, the park was in a state of disrepair. It was considered for the site of a new city hall that year, when Hooker’s city hall burned; ultimately it was decided to rebuild on the same site cater-corner from the park. But Academy Park’s state had attracted some notice, and it was placed under control of the Washington Park commissioners and Parks Superintendent Egerton. In September 1881 the Argus reported that “it is intended at once to lay out the Academy park with graveled walks, banks, mounds, plats and a large fountain. The work of removing the iron fence which surrounds the park has been begun.” In fact, the fence was auctioned off. Trees were removed, flagstone walks were laid, and the Evening Times and Morning Express routinely reported on minor updates to the park; the improvements cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $4300. They were delayed somewhat at times, as the Evening Times reported:

The park commissioners complain that the students of the Academy, and of the high school, have delayed the work of improving the academy park by persisting in using it as a play-ground. Hereafter, any person stepping on the grass of the park will be arrested.

Imagine that a park immediately adjacent to two schools might be considered a play-ground. We’ll have none of that. The work continued through 1882 and into 1883, presenting “an attractive appearance,” and making the park “one of the most attractive in the city.” And so it has remained.

It was joined by Lafayette Park to the west around 1920, when the entire block of residences above Park Place was removed to establish the new park in honor of the Marquis de LaFayette.

Leave a Reply