Another Albany bicentennial marker, and another one that long ago disappeared without a trace. So did whatever building it was originally installed on, probably another building after that, and, eventually, any evidence that any buildings had ever been there.

Bronze tablet, 16×22 inches, placed in wall of building south-east corner of North Pearl and Orange streets. Inscription:

“On this southeast corner of Orange and North Pearl Streets, was Erected the first Methodist Church 1792.”

In 1914, the Argus reported that it had been “removed by city authorities” from whichever building it was originally placed on. No reason was given, and we just have to assume it was never replaced. Today that space is just part of access to I-787, the little turning ramp that comes up across from the First Church in Albany.

In Albany’s various histories, we find barely a mention of this church. There is only rough agreement on when it was established, but 1792, give or take a few years, seems to be the most agreed-upon date. We can find no evidence of what it looked like, nor of how long this particular congregation occupied it.

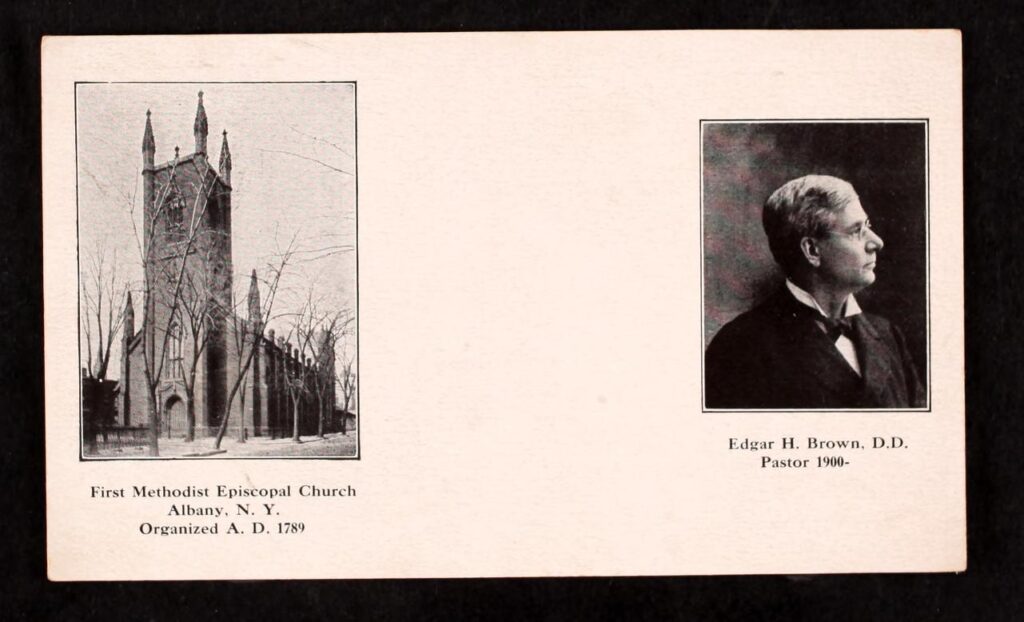

The reason for the confusion of when the Methodists began in Albany seems to center around which “beginning” one wants to credit. A 1903 Argus article, noting the repairs then being given to the First Methodist Church on Hudson Avenue at Philip Street, gives this early history:

“The First Methodist service ever held in the new world was in probability held at the quarters of Captain Thomas Webb, in 1765, at which time this British officer was barrack-master in this city. In 1789 Rev. Freeborn Garrettson preached in the State house and afterward organized a Methodist society. The first Methodist preacher stationed here was Rev. James Campbell, who, in 1790, was placed in charge of the Albany circuit. In 1791 the first Methodist church was erected and dedicated, a frame building on the southeast corner of North Pearl and Orange streets.

“This society which in 1798 was called the Albany City Station, removed in 1813 to a new church building on Division street, and in 1829 was called the Albany South Station. In 1844 it removed again to the building on Hudson avenue now occupied by S.L. Munson as a factory, and for years was known as the Hudson Street Methodist church.

“In 1883 it purchased of the First Presbyterian Society, its present edifice, and shortly afterward took the corporate title ‘The First Methodist Episcopal Church of Albany.”

That seems to comport with most other sources, so let’s say the first church was 1791 or 1792, but the congregation later dated itself to 1789, to the organization that Garretson put together. The history of this church has been harder than usual to put together, and that may not entirely be an accident, at least in the view of one author on Albany’s religious history.

According to David G. Hackett’s “The Rude Hand of Innovation: Religion and Social Order in Albany, New York, 1652-1836,” the first Methodist society was founded in Albany in 1792.

“By 1811 it remained a small congregation of less than one hundred journeymen, shopkeepers and laborers. Despite the city fathers’ public actions of support for the Methodists by providing them with free public land for their church, rarely did the names of their ministers appear alongside the names of the Dutch, Episcopal and Presbyterian ministers among the leaders of the first ecumenical organizations. The two instances when this did occur, in 1795 when a list of trustees was proposed for Union College and in 1813 when a similar list was proposed for the Albany academy, seem to have been efforts to demonstrate ecumenicism to the state legislature rather than to share power with the Methodists. The names of Methodist ministers do not appear elsewhere in the proceedings of these institutions. The new church also was internally troubled by a series of financial ’embarrassments’ surround the construction of their church and support of their ministers, as well as reversals in their membership due to migration and the widely diverging effectiveness of itinerant preachers. Not until at least the second decade of the nineteenth century would Methodism secure a solid foothold in Albany. In contrast, after the Revolution, Albany’s Presbyterian church grew rapidly in wealth and numbers to become the most influential church in town.”

It’s interesting that, in Hackett’s view, the Methodists were by design not the city’s movers and shakers, so some of their history and accomplishments may have been lost or simply not recorded in the journals of the day. It’s also interesting, and ironic, that perhaps the most prominent among the Methodists was Joel Munsell, Albany historian extraordinaire.

Hackett writes about Methodists and mechanics’ ideologies, and that they “appealed to the same constituency of less affluent journeymen, petty shopkeepers, and laborers.” He notes that Munsell was actually quite critical of Christian teaching and practice, and that his satirical journal The Microscope “regularly lampooned wealthy church members and in particular their ‘priests’ for living handsomely yet doing little to help the poor. Still, Munsell’s journals testify that he was frequently a churchgoer but not, at least until late in life, a church member.”

In fact, we wish we had discovered Hackett’s work prior to writing about the lost marker for Joel Munsell, for he relates that Munsell’s Microscope “incited older republican fears of a new evangelical union of church and state that would subvert the reason and therefore the independence of the common man . . . Rather than encourage church membership, however, these freethinkers wanted to replace the traditional habits of the workshop with their own societies of mutual improvement. What they offered Albany’s young, unchurched men was a way of knowing that limited the influence of evangelical thought while providing them with an intellectual setting of their own.”

So the history of the church quickly takes us away from its original location. By 1813 it was somewhere else, on Division Street; we haven’t found the exact location.

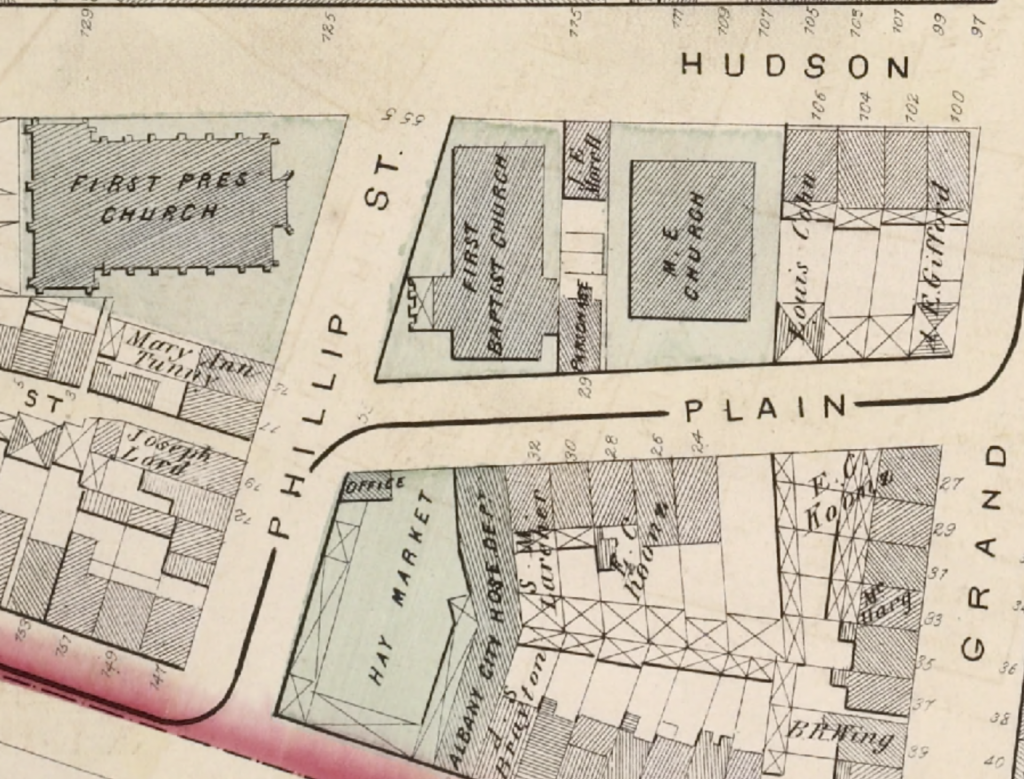

By 1844, it had moved west about two blocks and over to Hudson, with its back to Plain Street, very close to the First Baptist Church and the First Presbyterian Church, where it was known as the Hudson Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church (giving up, for the moment, its designation as “First”). When the Presbyterians moved up to Willett Street in 1884, the Methodists took the much grander Presbyterian church.

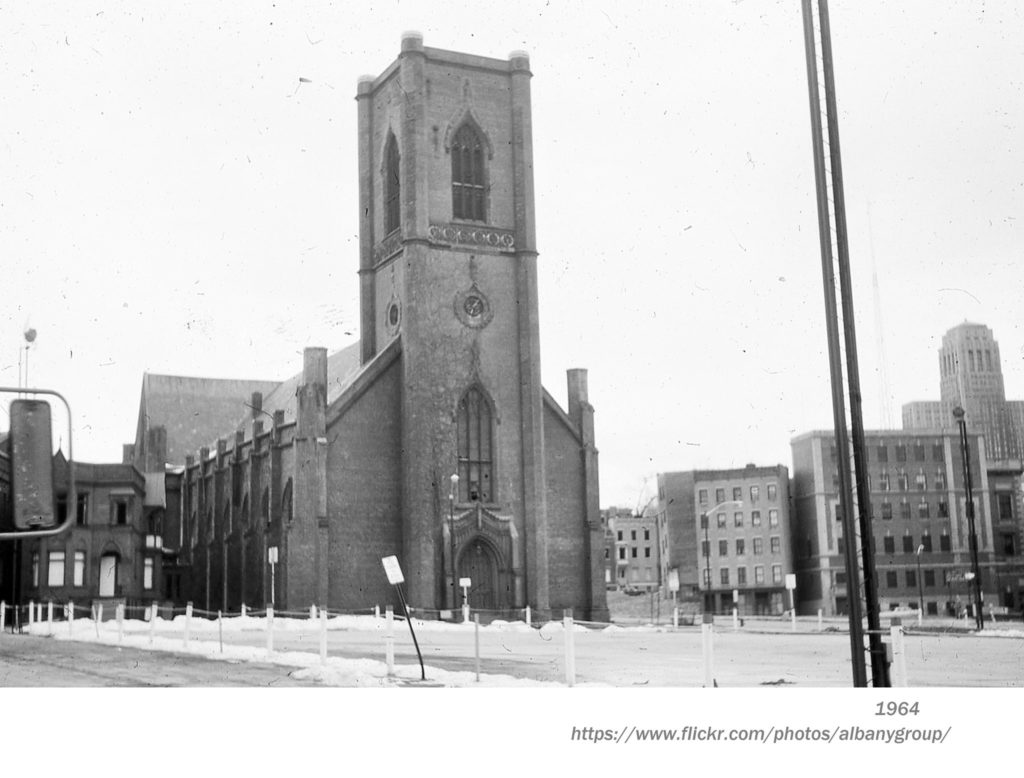

The Hudson Avenue church was then replaced by a new factory for the S.L. Munson shirt factory, which operated there at least through the mid 1920s. The Methodists remained in that location along what became the city’s market square until the development of the South Mall (and its attendant highway connections) called for the destruction of the entire neighborhood in the early 1960s. At first, it wasn’t clear that the First Methodist congregation would move anywhere; its trustees voted against a merger with Trinity Methodist, but changed their mind and approved a merger that was effective November 1, 1963.

“Proceeds that will come from the state for its church building and old parsonage building on Philip Street – more than $400,000 – will be given to the Albany Methodist Society to build a new Inner City Mission. The mission’s buildings will be razed for the South Mall project. More than $50,000 will go to Trinity Church and almost $10,000 to St. Luke’s. In addition, First Methodist earmarked more than $33,000 to pay its pension obligations to retired ministers who served the church in the past.”

The first church site

But there is no indication that the historical marker for the first Methodist church ever made the journey from Pearl and Orange to another location. We don’t have any indication of what happened to that first church built in 1792.

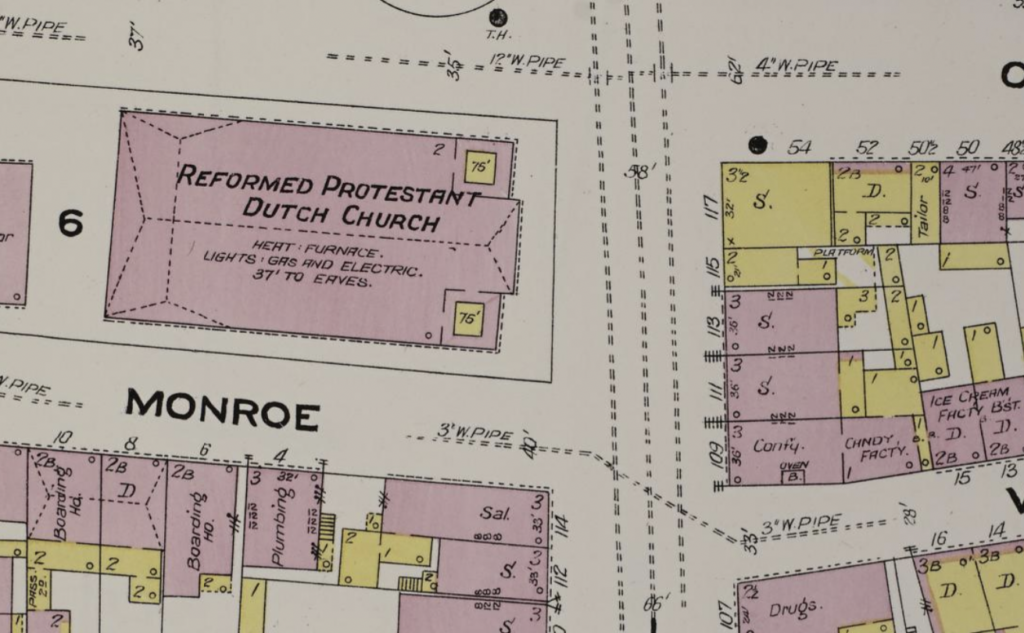

It was located directly across from the Dutch Reformed Church, also known as the First Church in Albany. In 1876, the location was occupied by the grocery store of James Rice. He appears to have been a tenant of Alanson Sumner – indeed, the building was sometimes called the Sumner Building. We can’t discern when the Sumner Building was constructed, so we’re not sure if the bicentennial plaque went on the Sumner Building or some predecessor, nor can we figure out why it would have gone missing by 1914.

Alanson Sumner, born at Edinburg in Saratoga County in 1801, held positions as assistant superintendent and superintendent with the Erie Canal. He later partnered in the firm of Clark, Sumner & Co., a lumber supplier.

Like most downtown Albany buildings, the Sumner Building had a variety of tenants through the years. At one time, D’Jimas Furs was there on the second floor, until it hopped across Orange Street for a street-level location. For a long time, the Sumner Building was home to Menter’s, a fairly large clothing chain that started in Rochester on the outrageous concept of offering credit to the working class – which makes its location on what was originally the working man’s church an interesting coincidence. Menter came to Albany in 1905 at 21 N. Pearl, above the Joseph Feary shoe store, and in 1920 moved to the Sumner at 119 North Pearl. They remained there until the 1950s, when they moved to 63-65 South Pearl, and then 44 South Pearl, before finally closing up as the last store in the chain in 1957. (Menter’s history courtesy of the Albany Group Archive).

It looks like the end of the Sumner Building came many decades after the plaque had disappeared, when that entire block and the one to the north of it, which contained the beloved Pruyn Library, were demolished to make an access ramp to I-787.

What’s there today? This, of course:

Leave a Reply