Continuing our review – our very slow review – of the historical markers that were placed around Albany in honor of the bicentennial of the city’s charter in 1886.

City Gate where News of Burning of Schenectady was Received.

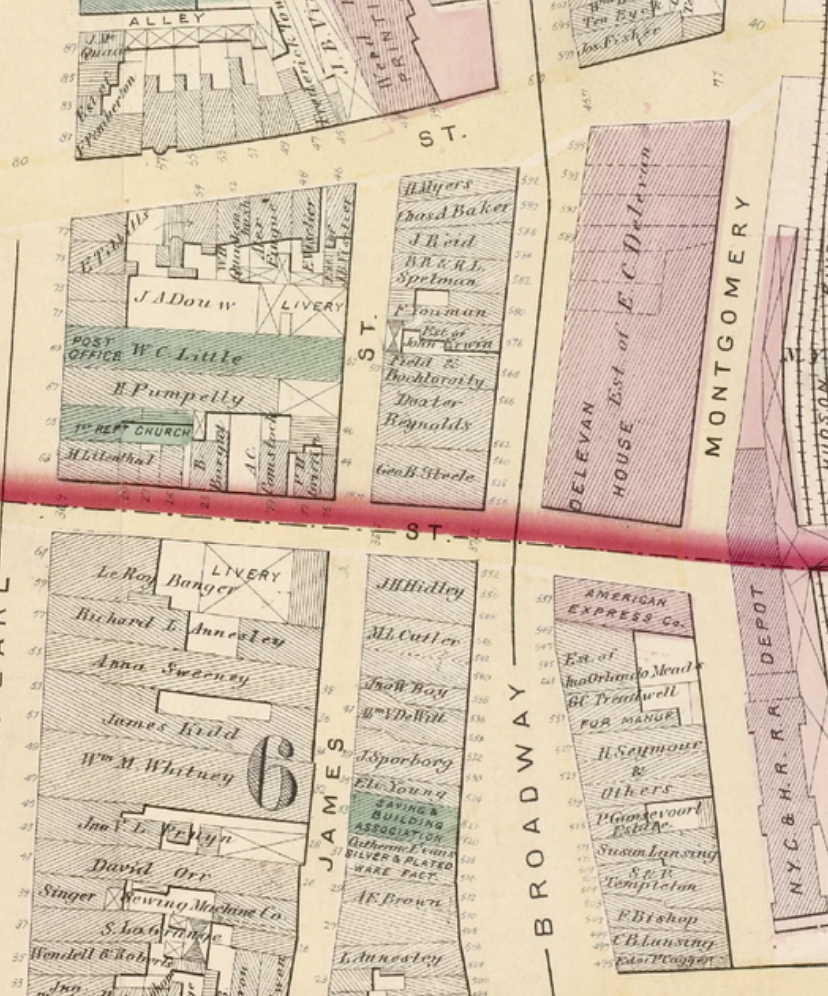

Bronze tablet, 24×32 inches, in face of north wall of American Express building, at Broadway and Steuben streets

Inscription :

“Near this Spot, a little to the East, Stood the North-East Gate of the City—Here it was that Simon Schermerhorn, at five o’clock in the Morning, ‘die Sabbithi,’ February 9, 1690 Himself Shot in the Thigh and His Horse wounded—After a Hard Ride in the Intense Cold and Deep Snow, By the Way of Niskayuna, Arrived with just Enough Strength to Awaken the Guard at the Gate and Alarm the People of Albany with the News that Schenectady was Burning and the Inhabitants Being Murdered Simon’s Son, Together with His Three Negroes, was Killed on that Fatal Night by the French and Indians. Simon went to New York soon after and Died There, 1696. To the North was the ‘Old Colonie ’ and the Road to the Canadas—Through this Gate in their Departure for the North Passed the Many Detachments of Troops Rendezvoused Here at Albany. The Remains of Lord Howe were Brought Back this Way and Burgoyne Returned a Prisoner.”

That’s a lot of text, and we’ve already seen that some of the original copy approved for these bicentennial markers was sometimes abridged by the time of casting. Not always – the “municipal” tablet, No. 2, is wordy as hell. But we do wonder if all this was actually cast.

The Argus in 1914 noted that this marker, which they shortened the title of to “North East City Gate,” “was originally on the American Express building on the southeast corner of Steuben street and Broadway. It has since been removed to the wall of the railroad station on the northeast corner of the same streets.”

There is a plaque commemorating Union Station on that corner, but as far as I can see no evidence of this “City Gate” marker, nor do I ever remember seeing it. I can’t find any further evidence that it was on the Union Station.

There’s a lot to the story on the marker, too.

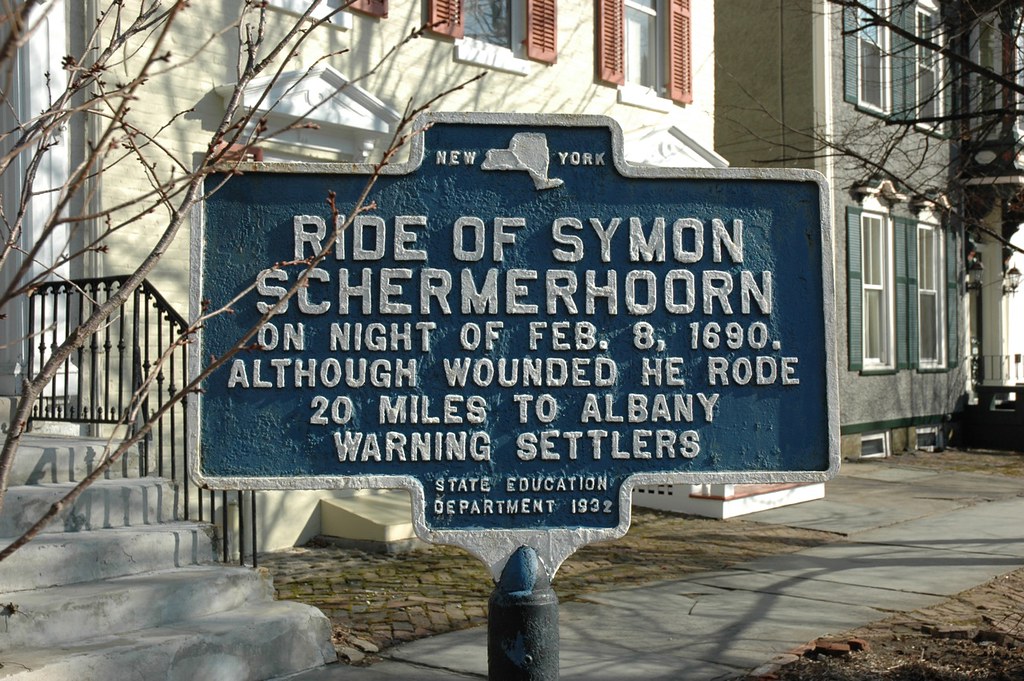

As the marker related, Simon Schermerhorn (and there are any number of variations on the spelling of his name) , with a bullet wound in his thigh, escaped from the massacre at Schenectady on the night of Feb. 8-9, 1690, and rode by horseback through Niskayuna to reach Albany and raise the alarm. We’ve already written extensively about the Massacre. It would be fair to say that my intense interest in local history was initially sparked by visits as a child to Schenectady’s Stockade, where the massacre took place, and by the historic markers that told some of the story there, including one honoring Simon Schermerhoorn (as that marker spells it).

Here’s how Thomas E. Burke, Jr. tells Simon’s story in “Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York 1661-1710:”

As if to heighten its impact, news of the killings was brought to Albany in the darkness before dawn by a wounded Symon Schermerhorn. Most likely, Schermerhorn slipped out the gate to Albany which the French has been unable to discover and spurred his horse for five hours through the snow to spread the alarm. A letter was immediately sent to the community at Esopus [Kingston] asking for assistance, and additional riders were dispatched to warn the farmers at Kinderhook and Claverack. An express also went north toward Schaghticoke but had to turn back in the face of high water, ice and snow. Little more was done for the moment except to fire the fort’s cannon as a warning to the nearby residents at Rensselaerswyck. The city’s garrison and inhabitants were immobilized, for word had been received “from Skinnechtady Informing us yt the Eneme yt had done yt Mischieffe there were about . . . 200 men but that there were 1400 in all; One army for Albany & anoyr for Sopus which hindered much ye marching of any force out of ye Citty fearing yt ye enemy might watch such an opportunity.” (from the Documentary History of the State of New York, edited by Edmund B. O’Callaghan.)

On Monday, February 10, some went to Schenectady to bury the dead and help the survivors, and a troop of 140 men, a mix of Dutch and Iroquois, set off in pursuit of the French-directed forces. They brought back four prisoners and killed others in skirmishes on the journey, but it may be that as many of the attackers died from the cold as from fighting.

Burke writes that the killings at Schenectady had a “dramatic impact on contemporaries. The Mohawks were reported to be ‘much amazed to see so many People murthered and Destroyed.’” The destruction of Schenectady was nearly total, burning all but five or six structures.

Happily, an historical marker commemorating Schermerhorn remains in Schenectady, but this bicentennial marker appears to be long long gone.