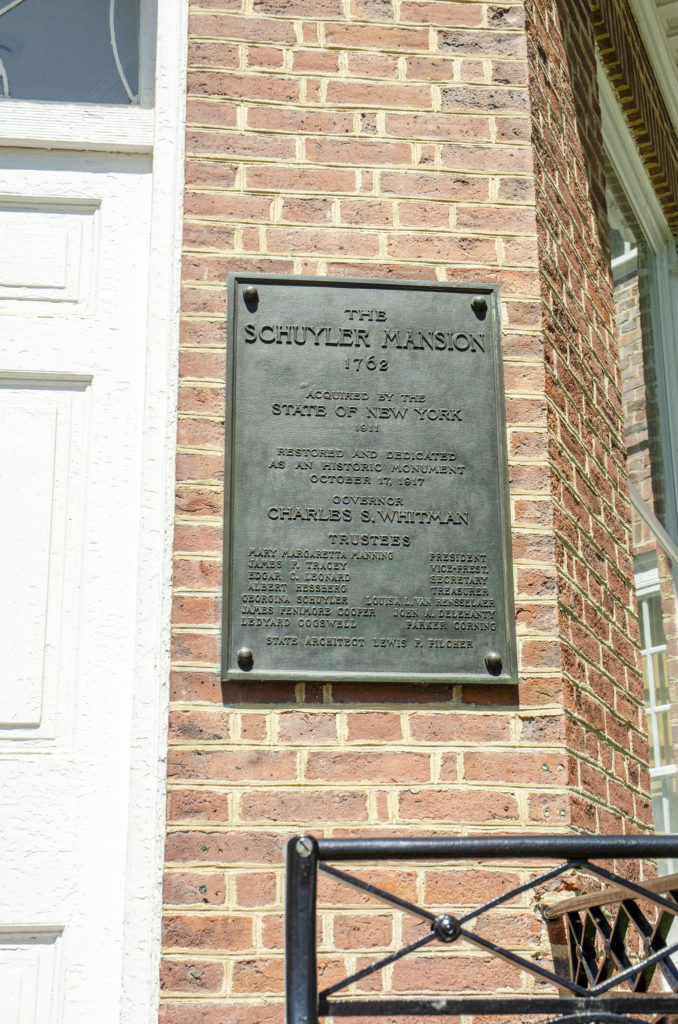

Continuing our series on the tablet placed in honor of Albany’s charter bicentennial in 1886. This one marked one of Albany’s most historic houses. It is fortunate that the house still stands and provides interpretation of events that occurred there. It is unfortunate that as far as we can tell, this historical marker has disappeared. As described by the Bicentennial committee:

Tablet No. 10—Schuyler Mansion.

Bronze tablet, 16×22 inches, inserted in front of wall inclosing grounds on Catherine street. It informs the beholder that there stood :

“The Schuyler Mansion—Erected by General Bradstreet, 1762. Washington, Franklin, Gates, De Rochambeau, Lafayette, and most of the great men of that time were entertained here. Gen’s Burgoyne and Reidesel as guests—though Prisoners of War 1777. Alexander Hamilton and Elizabeth Schuyler Married here in 1780.”

We have to start off by noting that this tablet was just plain misleading about who erected the mansion; a casual reader might think it was built for Bradstreet. Georgina Schuyler’s “The Schuyler Mansion at Albany….” from 1911 records that the house was built during Schuyler’s absence in England, by his wife Catherine Van Rensselaer, and advised by General John Bradstreet, who was “Schuyler’s commanding officer in the the ‘Old French war, his colleague in extensive land purchases, and, notwithstanding the twenty-one years between them, his warm personal friend.” Georgina has receipts and there is much detail on the costs of parts of the house.

The Albany Argus, when cataloging the fate of the bicentennial tablets in 1914, gave the story of the history of the tablet and of the house, and gave a tiny shred of credit to Bradstreet as something of a supervisor for the Schuyler family while Philip Schuyler was abroad:

“Instead of being placed on the building itself this tablet was attached to the Catharine street retaining wall at the corner of Clinton street, and its former location is indicated by four screw holes. Some years ago, for reasons unknown, it was removed and taken into the house. When the property was turned over to the State the tablet was discovered and is now in the mansion. It will, in all probability, be fastened to the building. The inscription states that the mansion was ‘Erected by General Bradstreet, 1762.’ A discussion of this point is contained in a paper entitled ‘When and by whom was the Schuyler mansion erected?’ which the writer [whom the Argus doesn’t name] prepared and read before Philip Livingston Chapter, Sons of the Revolution, on March 29, 1911. In it the conclusions arrived at were that ‘the Schuyler Mansion at Albany, N.Y., was commenced about May 12, 1761, under the supervision of Col. John Bradstreet, the agent of Col. Philip Schuyler, during the latter’s absence in Europe. It was completed under the direct supervision of Colonel Schuyler, after his return in 1762, he settling all the accounts.’ It is but proper that a suitable record should be made indicating General Schuyler’s part in the building of the mansion, which has always been connected with his name.”

We have checked with the Mansion and the Friends group, and neither has any idea where the tablet is today.

It’s hard to know where to begin with the complicated history of the Schuylers and Albany, or even of this mansion, which is now a museum owned by the State of New York. The popularity of the musical “Hamilton” created a bit of a craze for all things both Hamilton and Schuyler that could easily have overwhelmed some of the less pleasant truths about the family’s history and its relation to the Van Rensselaers, feudalism in New York under the patroon system, slavery, and more. However, both the state site and the Friends of Schuyler Mansion have been doing an unusually good job (as shown here) of presenting a more revealing picture of what went on on Schuyler lands than normally occurs with “great house” museums, which tend only to celebrate their provenance.

Joel Munsell, Albany’s premiere historical writer, wrote that the first Schuyler to settle on these shores was Philip Pietersen Schuyler, who shortly after his arrival from Amsterdam married Margarita van Slichtenhorst, the daughter of the director of Rensselaerswyck, the agent of the Patroon. They had twelve children (according to Stefan Bielinski at the New York State Museum; Munsell listed 10), who established the Schuyler family. Son Pieter was the first mayor of Albany; grandson Philip was the builder of this mansion, among many other things. Philip Pietersen Schuyler died in 1684 and was one of the early settlers buried in the Dutch church that stood in State Street near Broadway. Margarita controlled the vast estate, including acting as a merchant, until her death in 1711.

As we said, this house was built by Philip Schuyler, between 1761-65. Philip early on joined trade expeditions, dealing with the Iroquois; he learned to speak both French and Mohawk. He was commissioned as a captain in British forces during the French and Indian War in 1755, and went to Oswego with Col. John Bradstreet. He was elected to the Albany Common Council, owned the Greenbush Ferry, and built both this Albany house and the General Schuyler House on his “country” estate at Saratoga. He served in the colonial Assembly, and joined the revolution as a colonel in the militia, was elected to the Continental Congress, and served as a Major General in the Continental Army. Famously, as head of the Northern Department, he planned the invasion of Canada in 1775 and planned a defense against the British Saratoga campaign; he was court-martialed but acquitted for the loss of Ticonderoga. He resigned from the Army in 1779, and returned to the Continental Congress for two sessions. After the war, his holdings expanded vastly, and with it his use of slaves and tenant farmers. Between Albany and Saratoga, he owned at least 30 enslaved persons.

The remains of 14 enslaved persons were discovered in Menands back in 2005, during digging for a municipal sewer line. They were the remains of one man, six women, five children, and two infants, found near land owned by the Schuylers at Schuyler Flatts, and through DNA testing it was determined that they were slaves, presumed to have been owned by the Schuyler family. They were reinterred in a marked gravesite at St. Agnes Cemetery, with a memorial that says “Here lies the remains of 14 souls known only to God / Enslaved in life, they are slaves no more.”

The New York State Museum has an excellent webpage providing the bioarchaeology of the discovered individuals. While nearly all slaves passed through life barely, if at all, recorded, and the names of these burials can never be known, the Museum did a fabulous job of trying to humanize them, determining their height, physical conditions, and even what parts of Africa they had descended from.

Of course, the Schuyler Mansion has received significant attention as a result of the interest in Alexander Hamilton caused by Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical. We’re frankly confused by the recasting of Hamilton as an uncritical hero. In addition to his extremely anti-democratic pronouncements as a prominent Federalist, and his invention of the durable lease to extend the feudal control of the Patroon, he is a long way from blameless on the slavery issue, either. The Mansion’s Jessie Serfilippi has done a great job exposing his very problematic history.

If you grew up in the Capital District in the ’50s and ’60s, it’s highly likely that at some point you took a school trip to the Schuyler Mansion, and were told the story of the tomahawk mark in the banister, always ascribed to an “Indian attack.” And it’s not that there weren’t attacks on colonists by Native American allies of the British during the Revolution, and attacks against Native Americans as well. Significant parts of the state were in a state of terror throughout those years. So the story has some plausibility, except that Albany itself was never successfully attacked during the Revolution. In fact, it turns out that, if the gouge in the banister was the result of an attack at all, it was probably during a Tory attack in an attempt to kidnap Major General Philip Schuyler. Friends of Albany History has the full story.

There’s plenty of post-Schuyler history to this place as well, down to its eventual acquisition by the State of New York in 1911. But Julie O’Connor reminded us of one of its more interesting occupancies – the mansion was once an orphanage.

According to research by Lois Feister (original can be found here), the mansion was on the market in 1866, and it was purchased by St. Vincent’s Orphanage on Elm Street to be operated as a quarantine by the Daughters of Charity during a measles epidemic. She reports that 66 children were moved to the mansion. When the epidemic was over, those children returned to St. Vincent’s, but infants from an orphanage in Troy as well as children from St. Margaret’s Home in Albany were moved to the mansion, and eventually the needs of the orphanage required the addition to the rear of the house. It was ultimately the growing needs of the orphanage that led them to move to another site, and to sell the house to the state.

Leave a Reply