Updating my genealogy software for the first time in several years made me look at the state of some of my research. For starters, I’ve posted an updated version of my family tree cards which may be of use to anyone in my family.

I also found that I had done a lot of research and writing (a shorter piece was posted here) on my great great grandfather, but hadn’t put it all together and shared it on the web yet, so here it is — a tale of some of the earliest families to live and work in the Adirondacks, centered on William Kimbol Johnson:

William K. Johnson was born in 1830 in Essex County, New York. His parents were Philander Johnson and Lucy Kimbol (or Kimball — spelling was loose in those days). In later years, Lucy would become the “Mother Johnson” made very famous by the early Adirondack writers (though Philander was frequently referred to only as “Uncle”). I wrote a lot about Mother Johnson here. I haven’t learned more about the Kimbols, but this line of Johnsons had come up from Connecticut through Vermont in the years following the American Revolution, perhaps working in the iron industry, and when opportunities dried up in Vermont, they crossed Lake Champlain into Essex County, New York, then very much the wilderness but where some iron work was taking off. The Pecks and Grahams, families closely associated with this Johnson family, made the same journey at the same time.

Newcomb, New York

Unfortunately, nothing is known of William’s life until age 24, when he appears in the town of Newcomb, in Essex County. He had arrived there in March, 1855, and in that summer’s census his family included wife Martha and his first son, Charles R. Johnson, who was born in January 1854. Their second son, George E., would be born in March, 1856. Martha was the daughter of George Graham, who was born in Scotland, and his wife Harriet, who was born in Vermont in 1812. The Grahams had lived in Bridport, Vermont, and Crown Point, New York, and it appears that George died before 1860. Martha was one of six children, three girls and three boys; all of the boys worked as boating guides for Nathan Ingalls’s hotel in Crown Point in 1860, and they would have ties with the Johnson family for many years to come.

In Newcomb in 1855, the Johnsons seem to have been living on the farm of Charles and Elisha Bissell, who were among the prominent farmers of Newcomb as that community began to grow. The farm grew hay, oats and rye on 15 acres, and had some livestock. Newcomb, however, turned out to be only a waystation.

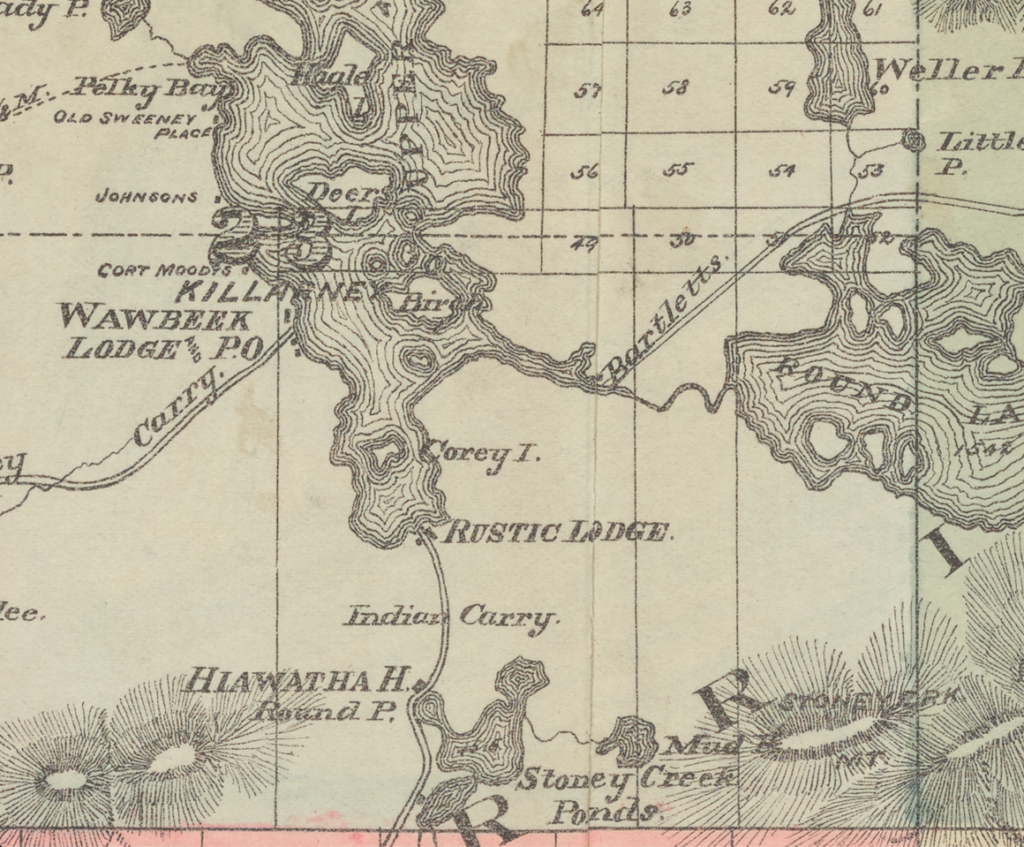

Indian Carry / Coreys

By 1860 the family had moved on to the area that would come to be known as Coreys, also known as the Indian Carry, in the town of Brandon (also known as South Woods, and later part of Harrietstown), Franklin County. William and his family were living there among other families who were entwined, commonly moving across the north country together. These included Jesse Corey, owner of the Rustic Lodge that was one of the very first of the legendary Adirondack destinations. Here, William Johnson, his sons Charles and George, his in-laws the Grahams and others would find work as the very earliest of the Adirondack guides.

Stephen Martin was there as well; he may or may not have been related somehow, but he sold land in the area in 1864 to William’s mother-in-law, Harriet Graham, land which she conveyed in 1880 to John and Nancy Dukett (Duquette). Nancy Dukett was Harriet’s daughter and the sister of William’s wife, Martha.

Also living among them was Scottoway Peck, who had left the Peck enclave in Wilmington for Brandon, possibly showing an earlier link between the Johnsons and the Pecks, possibly leading the way to a later link, when William’s grandsons Guy and Jesse would marry a pair of Peck sisters from Jay. It is hard at this remove to imagine what would drive families to move to what was essentially wilderness, and difficult-to-farm wilderness, at that, but sometime just before 1860 these families all settled together in this remote area just being discovered by the writers who were romanticizing the Adirondack experience. When it came to designating their occupations, however, all of them, even Jesse Corey, would list themselves as farmers; in later years, perhaps as the profession gained more respect or certainty, William’s sons would call themselves “hunters’ guides.”

William Johnson in the Civil War

Then came the Civil War. William K. Johnson enlisted in Co. C, 93rd Regiment, N.Y. Infantry on Sept. 28, 1861 in Minerva, NY, a town in southern Essex County. He was enlisted by Captain Dennis E. Barnes for a term of three years. At the time of enlistment, William was 32 years old. He was 5 feet, 5 inches tall, had a dark complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair. He listed his occupation as “laborer,” though in other military papers he listed “farmer.”

He was mustered in to Company C, 93rd Regiment, New York Infantry (also listed as 93rd NY Volunteers, and commonly known as “The Morgan Rifles”). He mustered in Nov. 20, 1861, and on Dec. 10 was appointed fourth sergeant — presumably a sergeant, the fourth grade. Below this were corporal (fifth grade) and private first class (sixth grade); above it were staff sergeant (third grade), first sergeant or technical sergeant (second grade), or master sergeant (first grade). Company C was also known as Captain Barnes’ Company, Butler’s Battalion, and Sharp Shooters. Butler was Lt. Col. Benjamin C. Butler.

The 93rd was organized at Albany, New York from October, 1861 to January, 1862 under Col. John S. Crocker, a lawyer from Cambridge in Washington County who had served in the State Legislature and was a friend of Governor Edward Morgan. Companies were organized by where they were recruited, which was geographically wide: Chester, Albany, Minerva, North Hamden, Cortland, Fort Edward, Cambridge, Boston, Argyle and Troy. Entering service as a Colonel, Crocker named his regiment the Morgan Rifles, in honor of the Revolutionary War rifle corps. The regiment was assigned to the Army of the Potomac, and was the headquarters guard of the army under McClellan, Hooker, Meade, and Burnside. Crocker took part in every battle of the Army of the Potomac, was captured in 1862 but traded for a Confederate officer, was wounded three times at the Battle of the Wilderness, and at Spotsylvania Court House.

The 93rd left New York March 7, 1862. While the Regiment mostly saw duty around White House Landing, Virginia, a major Union supply depot, in the summer of 1862, William Johnson was apparently detached for recruiting duty on August 9. It is not known where he went for that duty, but he was back with his unit in the fall. He was reported as absent, sick at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, southeast of Richmond, “since Aug 13” 1862; whether this was associated with his time on recruitment detachment is not clear. He was reported sick at Independence Hill, presumed to be a Virginia location, just a few weeks later, Sept. 7. He appears to have gone through the winter of 1862-63 without incident, but something unknown happened in March 1863, because on March 16 he is marked as “reduced to the ranks.” There is no further mention of the cause for this reduction in rank to private.

Re-enlistment

Through 1863, the 93rd saw significant action, including the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle of Gettysburg, and duty on the line of the Rapahannock. William seems to have passed through all this without injury or incident. In October he was noted as due a $100 bounty for having completed two years of service. As the Union struggled to increase the size of its armies, a general order had been issued in June 1863 authorizing a force to be known as “Veteran Volunteers.” This allowed current enlistees to close out their current obligations, re-enlist for a three-year period, and receive one month’s advance pay ($13), and a bounty and premium totaling $402, to be paid in installments. The total first installment was $40. (In that year, a skilled laborer might make an average of $1.75 per day; a journeyman mechanic might make $400 per year. Even unskilled laborers might make $1.00 per day, when there was work). Still, the inducement must have looked attractive to William Johnson, for on December 19, 1863, at Brandy Station, Virginia, he was mustered out and “discharged by virtue of reenlistment as a veteran volunteer.” He was mustered back in on the next day, receiving an instant bounty of $60, advance pay of $13 and a premium of $2, and was, like other veteran volunteers, “to have a furlough of at least thirty days in their states before expiration of original term.” He was given a medical examination, found free from “all bodily defects and mental infirmity,” and inspected by Lt. Waters W. Braman, recruiting officer of the 93rd.

It appears that the Regiment Veteran Corps returned home for January 1864 under the command of Col. John S. Crocker. They spent time in Albany and then in New York City on their way back to Brandy Station, but it is not clear if soldiers were allowed or able to return to their distant homes across New York State.

He was mustered back in as a private, still in Company C of the 93rd. On February 19, 1864 he was appointed corporal (“per R.O. [regimental order] 22 of Feb. 19. 64”). It was noted that he had due to him the second installment of his bounty as a veteran volunteer, $50.

Wounded at The Battle of the Wilderness

In May of 1864, the 93rd was engaged in the Battle of the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, a tangle of rough terrain in central Virginia that was the first battle of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s overland campaign. On the first day of the battle, May 5, William K. Johnson was shot through the thigh.

Lt. Bramhall of Company E wrote a letter to his brother on May 10, which was printed in the New York Tribune on May 20. In it he describes the Battle of the Wilderness, and describes an unnamed corporal who could very well be William Johnson. “One instance I would mention, I saw a corporal in the ranks of my company wounded in the leg, while in the act of loading his gun; he deliberately aimed his piece and fired, exclaiming ‘Take that,’ he then turned and said ‘Lieutenant, I am wounded and can do no more.’ He went to the field hospital and had his wound dressed, and soon after came back to the line, saying, ‘I must have another pop at the rascals.’ That corporal must be promoted.”

William’s captain, Dennis Barnes, a corporal and three privates from Company C were killed; William was one of 27 wounded (as was Lt. Bramhall). He was apparently moved to the United States General Hospital at Fairfax Seminary (Alexandria), Virginia, where on May 17 he was granted a furlough:

The bearer hereof, W.K. Johnson 93rd a Corpl of Captain DE Barnes C Company of the 93 Regiment of NY

aged 34 years, 5 feet 5 inches high, Dark complexion, gray eyes, Brown hair, and by profession a Farmer; born in the state of N.Y., and enlisted at Albany in the state of N.Y., on the 28 day of Sept eighteen hundred and sixty one, to serve for the period of 3 years, is hereby permitted to go to Crown Point, in the County of Essex, State of N.Y., he having received a FURLOUGH from the fourth [?] day of May, to the 16th day of June, 1864, at which period he will rejoin his Company or Regiment at Fairfax Semmary [sic], Va or wherever it then may be, or be considered a deserter.Subsistence has been furnished to said Wm. K. Johnson, to the 16th day of May 1864, inclusive.

Given under my hand, at U.S.A. Gen’l Hospl. Fairfax Sem’y, Va., this 17th day of May, 1864.

[signed] Daniel P. Smith, Surg., U.S. Vols., Commanding the Hosp’l.

It is not known with whom he would have stayed in Crown Point; by all accounts his wife and family were still in Brandon. Three of his wife’s brothers were in Crown Point then, working as boatmen (and probably fishing guides) at the hotel of Nathan Ingalls. It’s certainly possible William joined his brothers in law for a convalescent period, and Crown Point was much easier to reach then than the distant wilderness of the Rustic Lodge. (There were no Johnsons listed in Crown Point in 1860, though there were some in Ticonderoga, Westport and some other locations around Essex County.) In any event, his shot through the thigh had not healed when it was time for him to return to the regiment, and he saw George Page, M.D. of Crown Point, who wrote the following “Med. Art. for Ex. of Furlo” [sic]:

Crown Point June 15, 1864. I have this day examined William K. Johnson Co C. 93d Regt. N.Y. St. Vol. and find that he has a gun shot wound through the thigh. The wound is discharging profusely. He is improving but is not able to travel with safety and will not be for thirty days at least from the date of this.

Return from Medical Furlough

The regimental records show that Corporal Johnson returned from his medical furlough on July 27, 1864, when the regiment was in the First Battle of Deep Bottom (Henrico County, Virginia). It is not clear if he would have been stationed with his company at that time, and he was carried on the regimental records as “absent wounded” until Sept. 17, 1864. but he recovered and was able to avoid further injury during a series of engagements throughout the end of 1864 that made up the Siege of Petersburg. He was noted as having served at Poplar Spring Church (Peebles Farm) on Oct. 2, and at Boydton Plank Road on Oct. 27-28, 1864. He was on sick report for no noted cause on Nov. 9 and 10, and again Nov. 22 and 23, and he is noted as being owed the third and fourth installments of his bounty, a total of $100, in December. On January 10, 1865, he was promoted to sergeant, back to the rank he had lost for unknown cause near two years before. The next spring finally brought the Fall of Petersburg, on April 2, 1865, the day William received his second wound, this one characterized as “slight.” After the Fall of Petersburg came the pursuit of Gen. Lee until his surrender, April 9, at Appomattox Court House.

From Appomattox, the 93rd marched to Burkesville, Virginia, arriving April 13 and remaining there until beginning the march to Washington D.C. on May 2. They arrived in D.C. on May 15, and were part of the Grand Review, May 23. The 93rd was mustered out on June 29, 1865. During the course of the war, the 93rd lost 6 officers and 120 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded, and 2 officers and 130 enlisted men were lost to disease, for a total loss of 258 men.

William K. Johnson was mustered out as a sergeant. He had been last paid through Dec. 31, 1864. He was still due $190 in bounty money, and owed the U.S. $6.71; that amount is not explained. He also owed a debt of $17.00 to “G.C. Parmeter, Butler,” for an unknown reason. (I find no “Parmeter” in the regimental roster; though Butler was the Lt. Col., I suspect this is a job title, not a name.)

Return to Civil Life

Where he went from there is a mystery. He may have returned home to Martha and their sons, by then aged 11 and 9. He may have returned to Crown Point and whomever he had stayed with there during his convalescence. Or perhaps he moved to Westport, nearby on Lake Champlain.

By 1870, William and Martha were no longer together. She and her younger son George were living with Jesse Corey and his children Charles, Lem, and Charlotte, presumably working the farm and the Rustic Lodge. Martha was Jesse Corey’s third wife, and he had six children by the previous wives. Although Martha was only in her thirties when they joined (Jesse was around 60), they had no children together. Sometime before 1880, Martha’s brother Charles Graham moved to Brandon, living as a boarder with Martha’s son George, already a noted Adirondack guide, and working as a boatman. Martha’s mother, Harriet, had also come to the area by then, and Martha’s sister, Nancy Dukett, was there with her family as well. Martha and Jesse lived together until his death in 1896. Perhaps after Jesse’s death she had had enough of living in the wilderness, for she and her stepson Charles Corey, a hunter’s guide and Civil War veteran who had not married, had moved to North Elba by 1900, where he was farming. At some time before 1910 they moved to Keene. There she lived until her death in May 1911, at age 77.

That leaves the question of what happened to William. A special census was undertaken in 1890 for “Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, etc.” In that census, William K. Johnson, clearly the same William as shown by his enlistment dates, rank, and more, is listed as living in Schroon River, town of North Hudson, New York. He is listed as suffering from the disability of “chronic rheumatism”; under marks is the note “Gun Shot Wound Re enlisted.” This record notes that he served 3 years, 9 months, and 1 day. Looking at the pension records, it appears that he had filed for an invalid pension on Sept. 18, 1877. On May 25, 1896, a widow’s pension was applied for — by Mary A. Johnson.

A Second Family

Where did William go after the war? Whether he returned home to Coreys is not known, but his convalescence in Crown Point would suggest that he had some reason to be on the eastern side of Essex County. All that is known is that in June 1870, William had taken up residence in Westport, a small community 18 miles up Lake Champlain from Crown Point. He then had a wife, Mary, a one-year-old son named Fred, and a 5 month old son named John. He was working as a blacksmith and had a personal estate worth $100.

By 1880, the family was recorded as living in Elizabethtown; they appear to have been on a stretch of road now known as Megsville Road, well out of the village of Elizabethtown, and it’s possible that they had been there before, as this location is right on the border between Elizabethtown and Westport. (The section was also known as Jonas Morgan’s Patent). He was working as a carpenter; Fred, now 12, and John, now 10, were attending school, which was nearby. They lived next to Orin Taylor, who was a cooper, and not far from land marked as belonging to the Kingdom Iron Ore Company of Lake Champlain. It’s entirely possible the local residents of this out-of-the-way corner of Essex County hoped that iron would bring the prosperity it had brought to other reaches of the county, particularly Mineville and Jay, but the 1300 acres of undeveloped mining land accredited to Kingdom were part of a sophisticated stock fraud, and were tied up in a lengthy court action that wasn’t resolved before the 1890s. By then whatever opportunity was there had been missed. William and Mary were named, along with a great number of their neighbors, in a foreclosure action brought by a Susan Demmon on November 17, 1883, with an auction scheduled for January 5, 1884. The foreclosure included much of what was described as lot number six in Jonas Morgan’s Patent of 4800 acres lying in Westport and Elizabethtown.

Perhaps the failure of the area to boom, and the resultant foreclosure, is the reason William took his family away, to the area of North Hudson and Schroon River, two communities so close together, by Adirondack standards, as to be nearly indistinguishable. It was in Schroon River that he was noted, in 1890, as suffering from chronic rheumatism. The family was still altogether in 1892, in North Hudson. William and John were described as farmers, and Fred as a “pedler.” In 1894, William performed service for the Town of North Hudson that was described as “setting with board,” for which he was paid $12.50. (Most such payments were for ballot or highway services and fire fighting, so that nature of his activity is unclear; he is the only person for which that activity is described.) It is likely that William finished his life here, for on May 25, 1896, Mary applied for a Civil War widow’s pension. He was 66.

What happened to his new family after that is not clear. Mary is not found again with certainty. Fred appears to disappear entirely, and John may have moved to Lincoln, Vermont, where he may be the divorced 30-year-old John B. Johnson working as a teamster on a farm.

His First Family Continues

His original family went on. As already noted, Martha lived until 1911 with her stepson, Charles N. Corey. Her elder son with William, Charles, married a woman named Ellen around 1876. Continuing to live in the area that would be called Coreys, Charles worked as a hunter’s guide, and they had four sons, Lee Roy, Eugene, Guy and Jesse.

In 1897, William’s step-brother Charles Corey brought a foreclosure action against Charles Johnson and a number of others, which may have forced Charles Johnson’s move to North Elba, where they were farming in 1900, probably in the area along Cascade Lake called Cascadeville. He lived at least until 1910 by which time the family had moved to Keene, on Edmunds Hill Road, where they owned a farm. Ellen lived at least until 1920, but not much else is known about them.

Charles’s brother George appears to have remained in the Coreys area, where he married a woman named Emily or Emma around 1876. It appears they had no children, though he may have adopted children in a second marriage around 1910.

Charles’s sons remained the North Elba area. Lee Roy (who may have been called Leroy), who was born in 1877, reported that he was married in 1920, but nothing is known of his wife, and there is no evidence of children; when he registered for the WWI draft, he listed his mother as his nearest relative, so it’s unclear whether he ever really married. He died in 1946, and is buried in North Elba Cemetery on the Old Military Road.

Eugene, who was the second son, born in 1885, would appear never to have married. He didn’t occasion much mention in the newspapers, showing up as being paid for labor during a scrap drive in 1942, being fined for reckless driving in 1944, and operating illegal fishing tip-ups in 1947. He died that same year, and is also buried in North Elba Cemetery.

Guy Johnson

Guy Johnson, my grandfather, was born in 1887. He held various jobs as a laborer throughout his life, in North Elba, Crown Point, and elsewhere. He was working on a farm in Warren, Vermont, when he registered for the draft in World War I, and ended up in the Army, Company F, 101st Ammo Train, serving time in France.

When he returned he developed or maintained a relationship with his grandmother’s brother William Graham, a prominent farmer of Crown Point, frequently visiting William and wife Electa throughout the late and ‘20s. He lived in the Crown Point area for some time, working as a blacksmith on his return from the war and buying what was known as the Ingallston Place in nearby Factoryville. He was noted as hunting on some occasions, and may have occasionally worked as a guide.

In 1920, Guy’s younger brother Jesse, who had been born in 1890, married into the Alfred Peck family, which had moved from the Jay/Wilmington area into North Elba (the farm of Alfred Peck would later become the Craig Wood golf club). There had been a related Peck family in Coreys, as well, so the family connections went back a long way, and the Johnson, Peck and Graham families may have even been connected in Vermont around 1850.

Jesse married Agnes, one of Alfred and Eunice Peck’s 11 children, who at 20 was 10 years younger than he was. The long family connections and Jesse’s marriage probably brought Guy into close contact with the Peck family; in January 1927, a 39-year-old Guy married almost-19-year-old Gladys Peck, Agnes’s sister. Their first child, Lois, was born later that year, and the family began to split time between Lake Placid and Schenectady, where Guy is found working at General Electric in 1930. He, Gladys, Lois, and Phyllis were renting in a four-family house at 108 Johnson Street in Schenectady, a now-gone street between Chapel and Franklin Streets, just below Nott Terrace. Ultimately, from 1927 to 1947, Guy and Gladys would have 10 children, and there seem to have been times when Gladys and children would remain in Lake Placid while Guy worked in Schenectady. Later, the family would move to Schenectady’s Front Street, where the children would attend the Riverside School in the 1940s, and Liberty Street in the 1950s. Guy retired from General Electric as a crane follower in 1952. He and Gladys divorced, he moved to Jay Street, and Gladys married Paul “Ray” Bourdeau around 1956. Guy lived on until 1966. Gladys died in March 1972.

Leave a Reply