For a while now we’ve been interested in the story of Emmett O’Neill, the Schenectady Swindler. We hadn’t heard of him before he popped up along with some other research we were doing, but he was quite well-known and his crimes were widely reported across the state. (Various sources spelled his name O’Neill and O’Neil.)

On March 14, 1883, the Troy Daily Times reported on “The Ingenious Frauds of Emmett O’Neill – Swindling the Poor and Members of His Own Family out of Over $250,000.” The paper reported that the failure (bankruptcy) of Schenectady real estate and loan broker Emmett O’Neill had been recently announced, and that very shortly after it “became known that O’Neill had fled to parts unknown, and allegations were made that he was not only a bankrupt but a forger, embezzler and confidence man.”

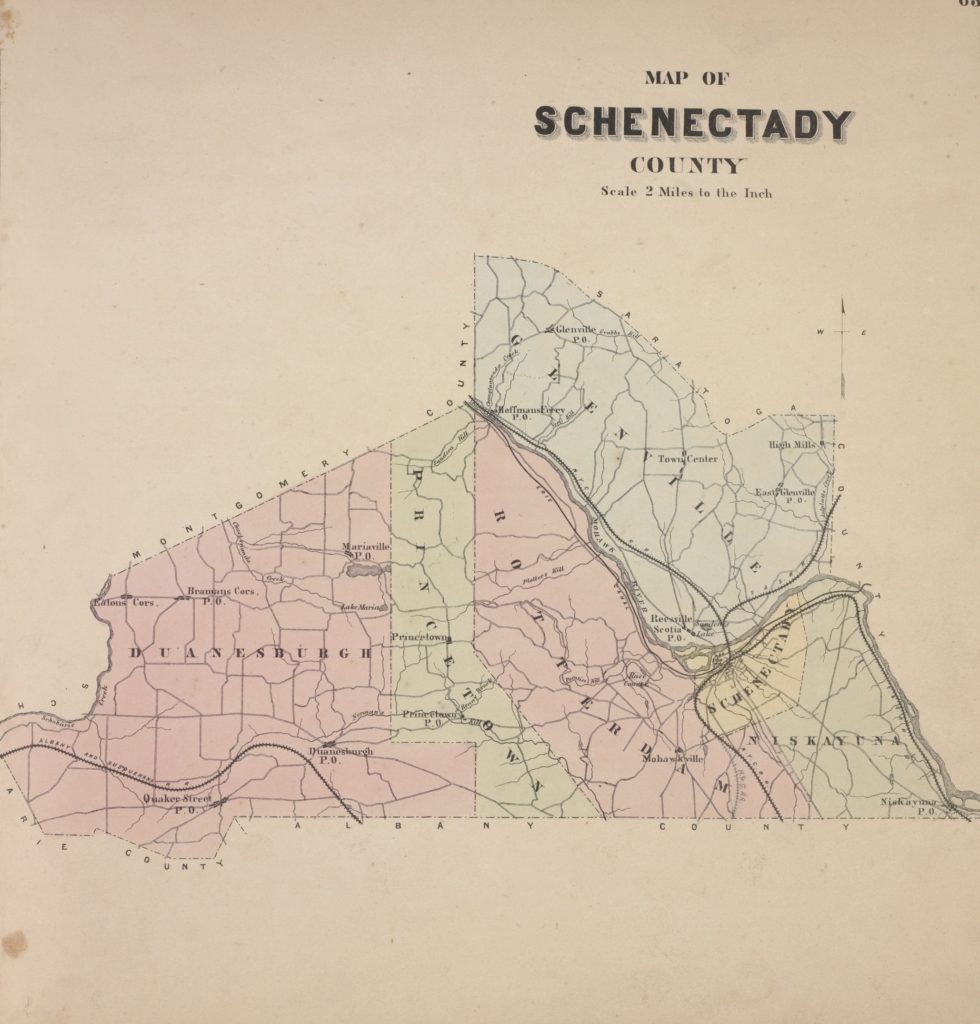

O’Neill, born 1840, was the son of a wealthy citizen of Duanesburgh (then spelled with its closing ‘h’), who was “the heaviest property owner in the town,” and highly regarded. Before the elder O’Neil (as he spelled it) died, he handed management of his estate, said to be worth $100,000, to Emmett. One calculator puts that at about $2.5 million today. “It was left to be evenly divided among six children after the widow’s support had been provided for, and Emmett was given charge of the estate. Succeeding to his father’s business, Emmett also had the respect and absolute confidence of the people. He was a fine looking man, an able lawyer and carried with him an affable manner and pleasing address which few people could resist, and with which few are gifted.”

He represented Duanesburgh in the Board of Supervisors, and served a term in the State Assembly. He left Duanesburgh around 1878 for Schenectady, where he opened a law office. In 1880 he became a partner in Schermerhorn’s real estate and insurance agency, “but the other members of the firm, believing he was reckless, retired him from the firm in February, 1881.” He joined a local drug firm, W.T. Hanson, in 1881, “but the partnership was quickly terminated.” After that, he did business on his own as a real estate and investment agent. In 1881, he was residing at 44 Washington Avenue.

“Going to Schenectady with an unsullied reputation O’Neill at once was recognized as a first class business man. Having the handling of his father’s estate and being presumably wealthy, he was elected a director of the Schenectady Bank.” He used his access to the books of the bank to determine “who had idle capital, and act accordingly.” If he knew someone had extra money and was earning only three percent at the bank, “he would visit him and offer to get him an investment at five or six per cent interest on first mortgages.”

This may need a little context for those familiar only with modern banking, loans and mortgages. For starters, at the time we’re writing about, not just anyone could deposit funds in a bank. Mortgages were often held by private citizens, and portions of the mortgage debt could be assigned to a third party. Loans between two private citizens could be made by way of a promissory note – and that “promise to pay” could be transferred to another person, much like a check could be signed over to another person, and the obligation to pay remained with the note.

Now, it’s also important to note that he was regarded as an expert penman, and that he quite publicly showed off his ability to fake someone else’s signature – anyone else’s signature.

“He could imitate any handwriting so closely that it was almost impossible to detect the counterfeit. On one occasion he went into the Carley House and copied a page of the hotel register on the opposite page so cleverly that the one was a fac simile of the other. Happening in a hotel one day when Judge Tappen came in, O’Neill went to the register and wrote the judge’s signature so nicely that when his honor had divested himself of his overcoat and stepped up to register he gazed with surprise, and remarked that he had forgotten he had registered.”

Innocent prank, or sign of a sociopath? Hmmm….

Even Widows Despoiled

O’Neill focused his efforts on farmers of Duanesburgh, where he was best regarded. He convinced them he could increase their investments, and in exchange presented them with forgeries. “He obtained possession of their money on plausible representations and gave as security forged mortgages, and where further proof was asked he would even forge assignments to the mortgage, including the county clerk’s certificate thereto and also a copy of the record. He would forge notes, and had eight notes out as collateral purporting to have been signed by Col. Church, each note for $5,000, only two of which are genuine.” He failed to record payments on mortgages, created new documents without destroying the earlier recorded versions, and recorded multiple mortgages for the same property. He took promissory notes against loans, and forged copies of the notes, negotiating them to a third party. As the newspaper subhead put it, “Even Widows Despoiled.”

“But to enumerate all his modes of crooked work would be tiresome. New schemes of his devising are still being exposed. To give a list of his victims would be impossible, as they are daily increasing in number. Nearly every person in the town of Duanesburg who had money is a victim, while in Schenectady the losers are counted by the scores.” Despite that, the newspaper then listed many of his victims under the not-at-all-pejorative subhead of “Some of the Losers.” They included the Trustees of Union College and the bookkeeper of the very bank where O’Neill hatched his scheme, and many members of his own family. “His mother and sisters are also left penniless.” A fund from the will of Catherine Duane, left in trust for the Sunday school of Christ’s Church and the Duanesburgh Library Association, was also entirely lost.

“Before leaving Schenectady on the midnight train, O’Neill made a parting raid upon Dorp pocketbooks. Taking a $100 greenback in his hand he went from store to store asking for change. Of course no one could change it, so the flying thief borrowed a few dollars from each storekeeper. He victimized over twenty residents of Schenectady by this little game . . . . O’Neill went to New York, where, it is said, he made an unsuccessful attempt to raise $20,000 on forged securities. He is believed to have gone to Europe. His wife, two little daughters and a son, are still in Schenectady.”

“There are no poor in the county”

His ruining of lives was absolute. John Liddle, a farmer in Duanesburg, was, along with O’Neill, a trustee in the estate of Liddle’s sister. When O’Neill’s empire collapsed, the sister filed suit against her brother for $7,000. Liddle hanged himself before the papers could be served. One Andrew Collins of Princetown was, late in 1883, detected in a series of forgeries, and he was said to have fled the country – “It is said he began his downward career as a result of losses sustained by the defalcation and embezzlement of Emmet O’Neill.” Years before the collapse, O’Neill had been an executor of the will of Ann Colliton of Knox, who directed that much of her estate be invested in mortgages, and the interest would be applied to support the poor of Schoharie County. Ann Colliton was a good and generous soul. Her executors, and the other heirs to her estate, were not. In 1880 it was reported that “thus far none of the proceeds of estate have been applied to the poor of Schoharie county.” They didn’t intend there to be . . . the executors and the heirs intended to apply a legal argument against using the funds in that way because, “as the poor are already cared for, there are no poor in the county.” Seriously.

However, O’Neill did not get to abscond to Europe as the Troy Times originally supposed. It was reported on June 20, 1883, that he had been arrested the day before in New York city by private detective Charles Morris, brought up to Albany by train and then taken in “a close carriage” to Schenectady. In Sept. 1883, it was reported that O’Neil was arraigned for trial and “at once pleaded guilty, and in a long speech detailed his wrong-doing.” On Sept. 10, he was sentenced to ten years imprisonment at Dannemora.

An item in the Washington County Post on May 30, 1884, reported that prison life suited O’Neil. “Emmet O’Neil, of Schenectady, who was sent to Dannamora [sic] for a term of ten years last fall for forgery, is said to be the most contented convict within the stockade. He is to be promoted from the clothing manufacturing department to the position of surgeon’s assistant in the hospital, and will not be kept in actual confinement.”

We don’t know about his post-prison life, but he died in 1892, at the age of 52, and is buried in Vale Cemetery.

Reader Tom Morgan was kind enough to share the details that O’Neill was discharged from Dannemora on March 12, 1890. Apparently he headed west, for his sudden death in Tacoma, Washington in January 1892 made news in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer:

T. E. O’Neil dies in Tacoma Jail

A Mysterious Case That Will Be Investigated by the Authorities

Tacoma, Jan. 26.–[Special]–Thomas Emmet O’Neil aged 55, a former Gray’s Harbor real estate and newspaper correspondent, died suddenly at the city jail this morning. At 7 a. m. Officer Higgins met O’Neil staggering about as if drunk on Pacific avenue. There was no odor of liquor about him and his condition mystified the police officer. He was placed in a cell an at 9 o’clock, was resting quietly, and asked the jailer not to disturb him. At 10:30 o’clock he was found dead cold in the cell.

Late last night O’Neil visited a Pacific avenue saloon, but refused to drink. He complained of suffering from a slight attack of pneumonia. Some friends secured a ticket for him, and he was to go to Snohomish by boat, to meet a former partner named Johnson. O’Neil stated last night that he had met with reverses at Gray’s harbor, and seemed a little despondent. A thorough investigation will be made, as it is thought O’Neil had been drugged.

He was the brother of a former mayor of Portland, and has a wife and two children in New York City and a brother in Montana. For several days after coming here he hid his identity at the hotel by registering under an assumed name. He was recognized on the street an reluctantly accepted the assistance of friends. His partner at Gray’s Harbor was a man named Johnson, whom he expected to meet at Snohomish. A few days ago Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Claypool indorsed a draft by O’Neil on his brother in Montana. It is believed by some that he was refused further funds by relatives and, having an attack of pneumonia, he took poison. No letters substantiating this belief were found. He was well dressed. An inquest and autopsy will be held tomorrow.

1892-01-27 Seattle Post Intelligencer

Thomas E. O’Neil Died of Heart Disease.

Tacoma, Jan 27.–[Special]–Coroner Frank decided today that Thomas Emmet O’Neil’s death was due to heart disease, and that an inquest was unnecessary. The funeral will be held tomorrow, in accordance with the following telegram, which was received today from the dead man’s brother, James O’Neil, of Colville Wash.:

Bury remains in metallic coffin, Catholic rites.

Dr. LaConner, of this city, identified the remains, and said O’Neil’s wife daughter and grown-up son reside at Schenectady, N. Y., and that deceased had lived at Montesano during the past year. Unfortunate real estate investments had left him penniless. The fact the $3 was found in his pockets discredits the rumor that O’Neil starved to death.

The Schenectady relatives ordered the body of O’Neil to be embalmed and shipped to that city.

1892-01-28 Seattle Post Intelligencer

Leave a Reply