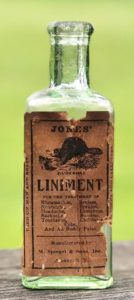

In talking about Lebbeus Burton of Troy, the druggist whose fortune founded an orphans’ home that is still in use today, we touched on the seemingly unlikely cure of Dr. Jones’ Beaver Oil (also sold as Beaver And Oil Compound, “for the treatment of Rheumatism, Neuralgia, Sore Throat and Quinsy, Headache, Toothache, Backache, Bruises.”

Which made us wonder, who was Dr. Jones, and did he squeeze those beavers himself? Well, it turns out there were two very well-known Doctors Jones in Albany, legends in homeopathic treatment – and that neither one seems to have had anything to do with beaver oil.

Which Dr. Jones?

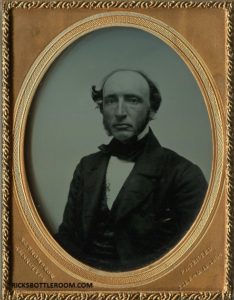

The first Dr. Jones was Albany’s Erasmus Darwin Jones, M.D., who, according to Volume 52 of the Transactions of the American Institute of Homeopathy, was born in Upper Jay, up in Essex County, in 1818, the son of a doctor who was the son of a doctor. He studied with Dr. Alden March at Albany Medical College, graduating in 1841. He returned to Keeseville and then became keenly interested in the emerging principles of homeopathy. In 1846 he moved to Albany, where he remained until he died in 1895. While there, he was one of the founders of the Albany Dispensary and Homeopathic Hospital, as well as founding the New York State Homeopathic Society. He was also a very busy Mason.

According to Amasa Parker’s “Landmarks of Albany County,” “for forty-five years he conducted a large, successful and lucrative practice. He was noted for self-sacrificing devotion to the interests and welfare of his numerous patients. He excelled in industry, accuracy of discrimination, untiring patience, and a never exhausting wealth of resources in all difficult and complicated cases. And through, and with, these characteristic qualifies, there was always exhibited a kindliness of feeling, courtesy of manner, and fervency of zeal, that caused both devoted friends and professional associates to sincerely regret that the infirmities of advancing years had, in 1891, brought forced retirement from active and effective work, in the field where his tact and skill were so long recognized as qualities developed to a degree to which few younger men could ever hope or expect to attain. He died August 17, 1895, at the age of seventy-seven years.”

Dr. E.D. Jones was on the medical staff of the Albany City Dispensary, which was located at 7 Plain Street in the 1870s. (“Old and partly torn pieces of cotton and linen for bandages are always acceptable.”) For several years around 1879, E.D. Jones was listed as the manager of a business at 99 North Pearl Street, selling the Holman Liver and Ague Pad and “Medicinal Absorptive Body and Foot Plasters and Absorption Salt for Medicated Foot Baths.” Promoting cure by absorption rather than dosing, the remedies were said to be the most effective for all diseases arising from malaria or a disordered stomach or liver, “and it is a well known fact that nearly all the diseases that attack the human body can be traced directly or indirectly to these two organs.” So while we find numerous ads connecting Dr. Jones to the Holman Liver Pad, we find no connection at all to a product called Beaver Oil.

So, perhaps it was his son, Charles E. Jones, the fourth-generation doctor in the family. He practiced alongside his father, was just as involved in the Homeopathic Hospital and the local homeopathic medical society. He died young, at 50, in 1899. In 1903, he was to be honored: “In connection with the building of the new Homeopathic hospital there is a desire on the part of the friends of the late Dr. Charles E. Jones to create a suitable and lasting memorial to his memory . . . It was well said of him: ‘His life was devoted to the alleviation of the pains and ills of humanity, and it mattered not to Dr. Jones whether his patient had a well-filled purse or was among the poorest of the poor. The sufferings of this world were made less for those who were within the reach of his activity.’” There is no mention of beaver oil.

Dr. Jones was really Dr. Spiegel

In fact, searches through newspapers of the day don’t turn up the brand “Dr. Jones’ Beaver Oil” until 1903, when both Doctors Jones were well gone from the scene. And every advertisement (and legal action) that we find instead connects the product with another doctor (perhaps), Morris Spiegel.

Morris Spiegel was a native of Austria (sometimes reported as Germany), born around 1837, who came to the US around 1860. Early on he was listed as a druggist for Paulus and Sons, then sometimes as a physician, and later as a patent medicine manufacturer. At some point he settled his manufacturing at the corner of Delaware and Catherine (178-180 Delaware), which was also his home late in life. For someone who was in practice for so long in a single city, it’s surprising how little mention he received, and we couldn’t find any confirmation of his medical background.

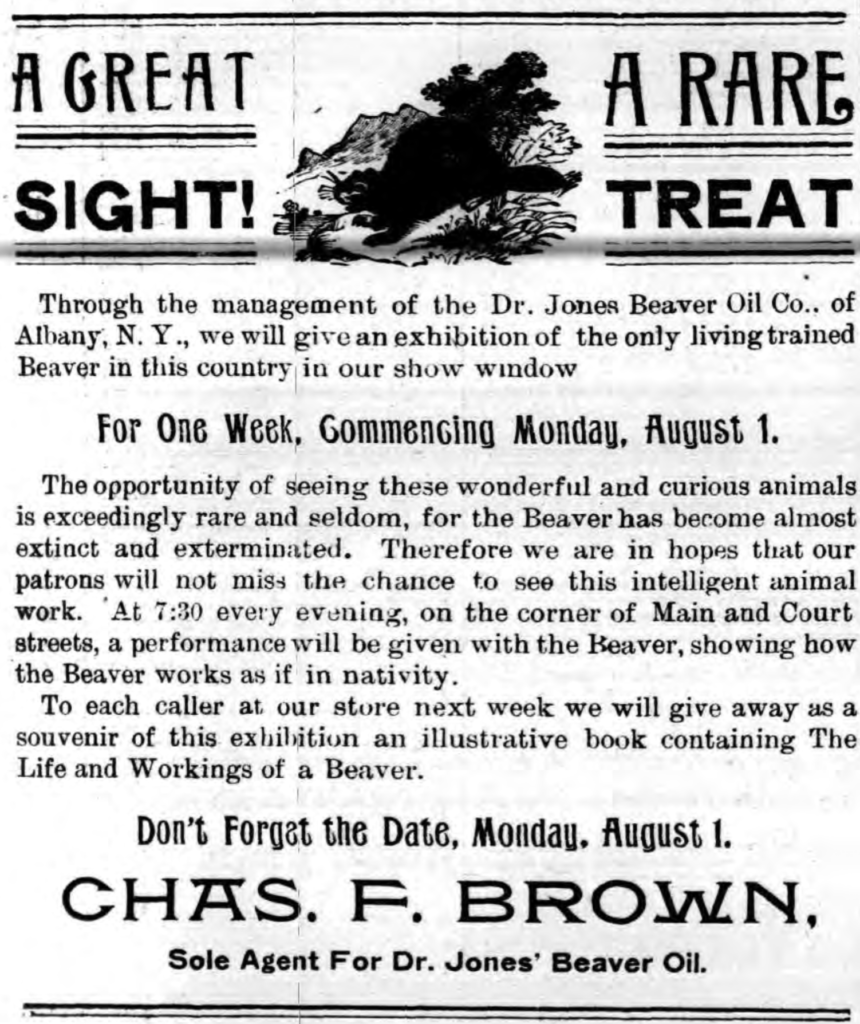

In 1903, we find the first mentions of Dr. Jones’ Beaver Oil, and of Dr. Spiegel’s beavers. The Waterbury, CT Evening Democrat takes note from nearby Brooklyn, CT that:

“A large crowd witnessed the exhibition of a live beaver owned by the representative of the Dr. Jones Beaver Oil Co., on the lot at the corner of Bank and South Leonard streets. The beaver performed some clever tricks. The exhibition will be repeated to-night and to-morrow night. The beaver, which is on exhibition in Walker’s drug store, is attracting much attention. A.C. Walker has made arrangements with the Dr. Jones Beaver Oil Co. to exhibit their live beavers in the window of his drug store for three days, commencing Thursday morning, November 5.”

This exhibition (the beavers were named Fannie, after Spiegel’s wife, and Harry) went on all over New York State, and for several years. We found references to further beaver displays in Auburn, Cortland, Port Jervis, Hornellsville, Hudson, Salamanca, and more. If it’s hard to understand what the excitement was about, it should be recalled that in New York, the beaver was pretty much extirpated by this time. In the 1890s, they were almost completely eradicated from the Adirondacks (a combination of extensive trapping and loss of habitat from massive logging). Starting in 1901, the State of New York bought about 20 beavers from Canada and released them near Old Forge (there’s an historical marker for that), and later brought in more creatures from Yellowstone and scattered them around the Adirondacks. In a little more than a decade, the population went from less (possibly way less) than 100 to more than 15,000 beavers across the state.

Beaver Seizure

So Spiegel’s cure-all came at a time when there was already significant public interest in the beaver. And at a certain moment, the State of New York also took an interest in Dr. Spiegel’s beaver, as reported in the Plattsburgh Sentinel, Nov. 9, 1909:

“Dr. Morris Spiegel, manufacturer of beaver oil, whose laboratory is in Albany, has started an action to recover two thousand dollars” from the state forest, fish and game department. “To that amount, he says, his interests were damaged by the seizure last spring of a beaver which the protectors found on Dr. Spiegel’s premises. The animal was sent to Lake Placid and released in one of the beaver colonies which the state has established.” The State charged that Spiegel was trying to procure additional beaver from one those those colonies, in violation of the law then prohibiting trapping, shooting, possessing or interfering with beaver, which that year were estimated to number 500. “As they breed very fast it is the belief of the state officials that, if they are unmolested there will be thousands of them in the state in a few years.” Dr. Spiegel said the law couldn’t apply to him because he had owned the beaver before a new law went into effect, but the State didn’t see it that way.

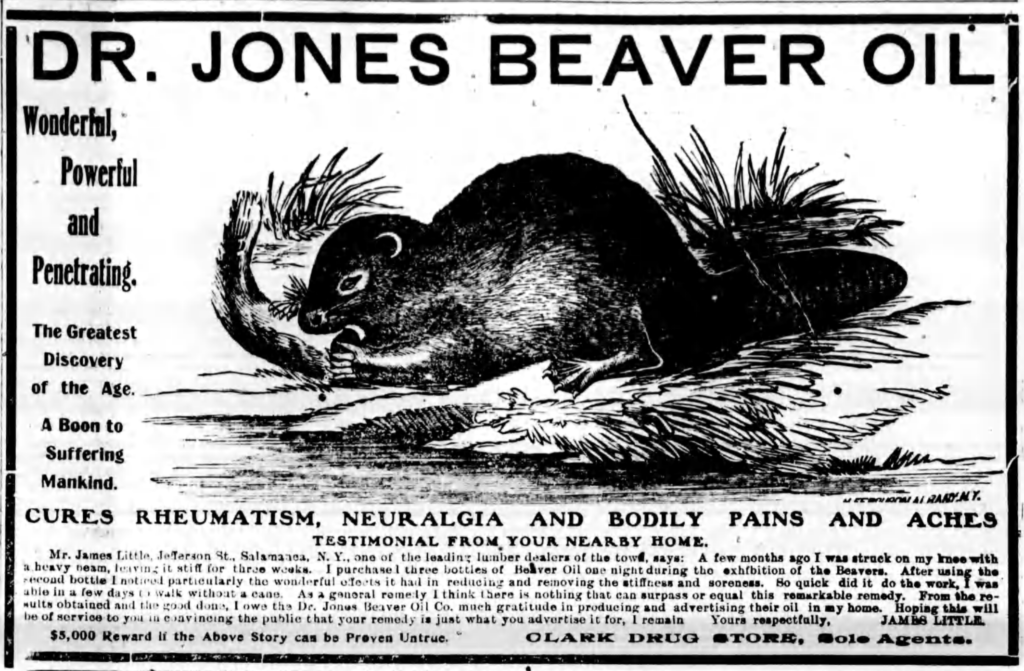

A consumer could certainly be forgiven for thinking that a product named beaver oil, with a picture of a beaver on the label, and which was represented at drugstores across the state by showings of live beavers, might actually contain some sort of extract of Castor canadensis. However, such a consumer would be completely wrong. Around this time, Spiegel’s beaver wasn’t the only thing that caught government interest. “Nostrums and Quackery,” a collection of articles on quackery by the American Medical Association, tells the story that led to a 1909 decree against Dr. Jones’ Beaver Oil as manufactured by Morris Spiegel of Albany, N.Y.

It was sold “for the treatment of Rheumatism, Neuralgia, Sore Throat and Quinsy, Headache, Toothache, Backache, Bruises.” Although “beaver and oil compound was ‘warranted as represented’ there was found no beaver oil, nor in fact, any animal oil.” In fact, it was found by the US Department of Agriculture to be essentially gasoline, oleoresin of capsicum (the ingredient in most pepperspray), and oil of sassafras, and no animal oil. “The product was declared misbranded.” The decision was rendered and Morris Spiegel was reported to have complied with the terms of the 1909 decree, after which the product became Dr. Jones’s Liniment. You can sell gasoline for people to rub on their skin; you just can’t call it beaver oil.

He wasn’t done with the “Dr. Jones” brand, however. “Dr. Jones’ Sangvin” was another preparation of Dr. Spiegel’s, which he claimed in use from 1910. It was described as “A vegetable medicine or purifying the blood and strengthening the nerves and for stomach, liver and kidney trouble and for scrofula, tetter, and hives and other skin diseases arising from impure blood.” He was publishing it as a proposed trademark on Oct. 24, 1911, “The name ‘Dr. M. Spiegel’ being a facsimile-signature of the proprietor of the mark, the name ‘Dr. Jones’ being disclaimed.”

In 1915, Spiegel was charged again for misbranding, this time for “Dr. Jones’ Liniment,” which was intended to treat all the same maladies as Beaver Oil treated, plus chilblains and “frost bites.” It claimed that the liniment had been in use since 1869, and that it was guaranteed under the Food and Drugs Act, June 30, 1906, by Dr. M. Spiegel, Manufacturer. (In fact, its advertising and accompanying booklet offered it for muscular rheumatism, and sciatica. Once again, the government found this to be a gasoline solution that now included oleoresin of capsicum, oil of sassafras, methyl salicylate and volatile oil of mustard. “Fatty oil, other than that from capsicum, was not indicated.” It was found to be misbranding to say that it contained medicinal agents that would cure rheumatism or sciatica, as it contained nothing of the sort. Spiegel pled guilty and paid a fine of $25.

Morris Spiegel died in a Philadelphia sanitarium where he was trying to “recuperate from an illness from which he had been ailing for some time,” in 1917. The Albany Evening Journal said he was born in Prague, Bohemia, and “during his many years in business Dr. Spiegel gained a statewide reputation as a liniment manufacturer.”

Even after his death, in 1919 we find a number of ads, primarily in Schenectady, for Dr. Jones Liniment, “The Good Old Fashioned Beaver Oil.” What we don’t know is who was producing it at that point, or for how much longer it went on. We do know that it continued to contain 0% beaver.

Leave a Reply