Looking up these old local stories is nearly always a venture down a rabbit hole, and it’s usually a question of where to stop. One little detail catches the eye, and I start to find out more about that, and it leads to another detail, which leads to a huge revelation, which leads to who knows what. That’s what happened with this, which I thought was just going to be about a fortune founded on beaver oil and root beer. Along the way, this story gathered up a tragic death, orphans, an old man marrying his housekeeper, and great charity. In the middle of it all, a house that still stands.

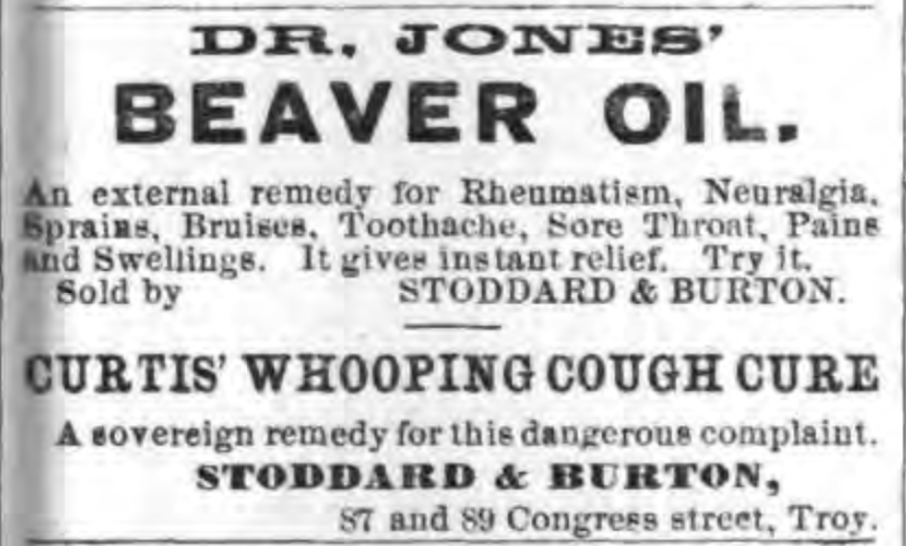

In looking for something else entirely I ran across this ad in an 1870 edition of the Troy Daily Whig for Dr. Jones’s Beaver Oil. We may need to talk about Dr. Jones and his Beaver Oil, later marked simply as liniment, at some later time. The point here was that both his Beaver Oil and Curtis’s Whooping Cough Cure were available at the establishment of Stoddard & Burton, 87 and 89 Congress Street in Troy. And that made us wonder about Stoddard and Burton.

It began as a drugstore run by William C. Badeaux in 1847, at 54-1/2 Congress Street. It became Badeaux and Stoddard in 1848, at 55-1/2. In 1850, it was just E.W. Stoddard, operating under a few variations of his name (all this according to Weise’s “Troy’s One Hundred Years.”)

Lebbeus Burton of Norwich, Vt. joined as a clerk in 1848, and after seven years became a partner under the name of Stoddard & Burton; later Stoddard sold out (or died) and it was just L. Burton & Co., with various partners. At some point the company moved to 87 and 89 Congress, which was just a couple of doors west of Fourth Street on the north side. In 1897, as described in Anderson’s “Landmarks of Rensselaer County,” Burton’s was the second oldest wholesale drug firm in Troy, and his success was attributed to “the system of paying cash and receiving the benefits of discount, being among the first in the trade in the city to adopt that system, and he credits that as being one of the causes of his success.”

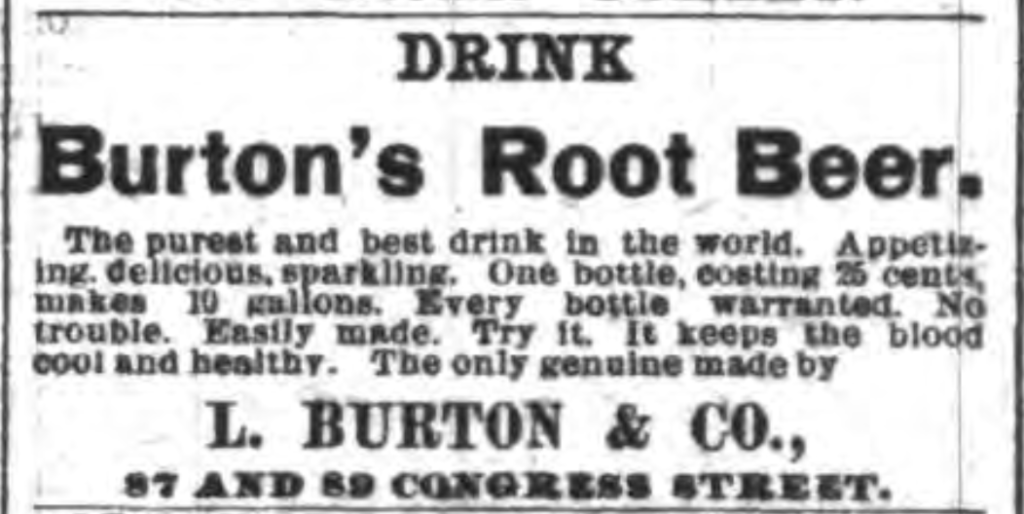

No surprise at all then that one of the biggest drug stores in the city would be selling all kinds of “medicines” of the day, including Beaver Oil. In 1890, Burton was selling his own brand of root beer – at a time when what you bought was the extract to make your own. “The purest and best drink in the world. Appetizing, delicious, sparkling. One bottle, costing 25 cents, makes 10 gallons . . . Try it. It keeps the blood cool and healthy.”

“One of the handsomest places in Troy”

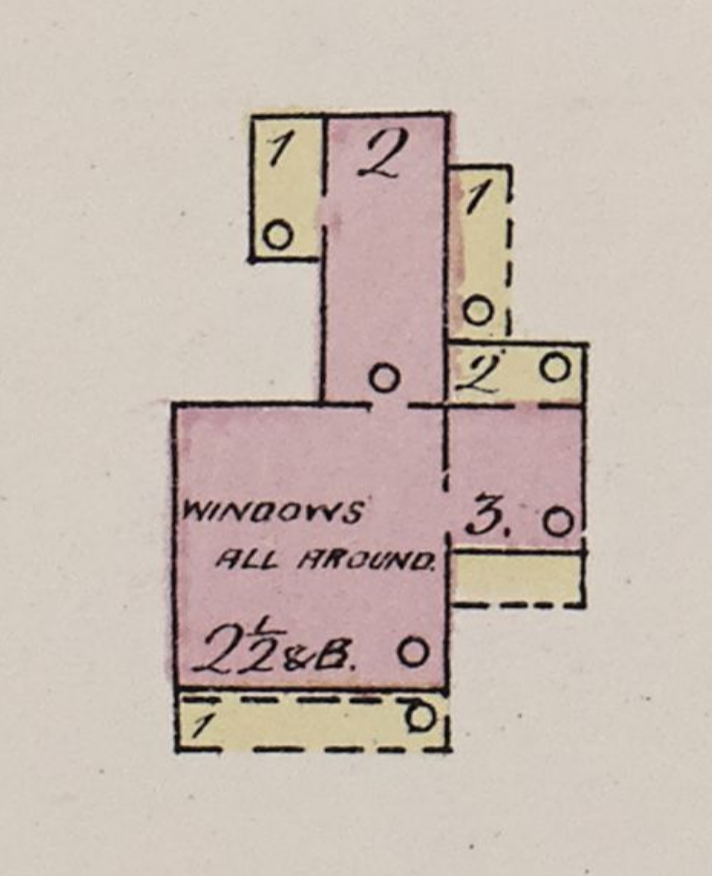

Anderson’s “Landmarks” made interesting mention of Burton’s home: Burton had a place on Ninth street called Sunnyside, “one of the handsomest places in Troy; the lawn contains several acres handsomely laid out and ornamented with beautiful trees, shrubbery, and flowering plants.” We haven’t located a drawing or photograph of Burton’s Sunnyside in its prime, but we gather it was rather a grand home. The surrounding area was also known as Sunnyside, East Sunnyside and West Sunnyside, with a number of other families claiming Sunnyside as their address, but they don’t appear to have been an actual part of the Sunnyside estate.

It appears that Lebbeus Burton, who was born in 1826, only married relatively late in life. In 1885, he married Mrs. Rachel Lake Burton, who had previously long been married to Lebbeus’s older brother, a harness-maker named Zimri who died in 1883. In fact, in the 1855 census, 27-year-old Lebbeus was living with 39-year-old Zimri and 37-year-old Rachel. This arrangement continued at least through 1871, when they were all at 107 Third Street.

This late marriage didn’t last very long. On August 19, 1888, Rachel was climbing an embankment in the orchard at Sunnyside, and fell and struck her head on a spike in the ground. This was reported far and wide in the state, and the newspapers said she was “about 60,” but it appears she was actually about 70. They had been married just short of three years; she had no children by Zimri or Lebbeus.

On October 22, 1900, 73-year-old Lebbeus married 40-year-old Miss Mary Agnes Cullen, a native of Ireland who was listed in that year’s census as his housekeeper. Her sister Elizabeth was also a servant in the household. Shortly thereafter, Lebbeus died, on January 28, 1901. He is buried in Oakwood Cemetery (Section B, Lot # 69).

That left Mary with the Sunnyside estate and his fortune; he had about $70,000 in real estate and $125,000 in personal property, and $160,000 of that was left to Mary, with a few thousand dollars each also given to various relatives. Mary apparently set to work putting that fortune to good use.

When Mary Agnes Cullen Burton died Nov. 3, 1922, her obituary noted some of her many works of charity. “She was a member of St. Patrick’s Church in which she evinced a deep interest. Among some of her gifts to St. Patrick’s Church are the new marble altar and a beautiful memorial window. To the St. Vincent Female Catholic Orphan Asylum on Eighth Street she gave her former residence with its spacious grounds at Sunnyside. Mrs. Burton had dispensed many acts of charity in an unostentatious manner.”

The Burton Memorial Home

From that point forward, Sunnyside was known as the Burton Memorial Home, used by St. Vincent’s Female Orphan Asylum as its summer home – beginning in 1922, and perhaps earlier, groups of orphans were brought to the summer location each year for a respite in a more spacious, if not significantly more rural, location than the Eighth Avenue asylum. In 1931, for example, the Burton Memorial Home opened at the close of the school year “and will remain open until about the second week in September. There are 160 girls in residence at the institution, where spacious grounds, splendid playground facilities and attractive living quarters make an idea resort for the summer months. A number of improvements have been made on the grounds and buildings since last year. New cement walks have been laid through the lawns, additional playground equipment has been installed and the institution chapel has been thoroughly renovated.” There was baseball, volleyball, other sports, crafts and even a swimming pool.

The orphan business started to wind down some years later, and in 1946, St. Vincent’s Home sold its 180 Eighth Street building to RPI for post-war housing, and transferred the remaining children under its care to Albany’s St. Vincent’s Home. The $85,000 received in the sale “will be used entirely for benevolent and charitable purposes and for improvement of land and buildings at East Sunnyside in Troy” – meaning they still held on to Sunnyside even though it was no longer being used, apparently, as a summer orphanage. In 1949, the name of the St. Vincent’s Female Orphan Asylum, originally organized in 1863 by the Sisters of Charity, was changed to St. Vincent’s Institute. “The assets of the former asylum, consisting of real estate known as Sunnyside, Ingalls Avenue and Ninth Street, and a substantial financial legacy received from the estate of the late former Mayor James W. Fleming will be taken over by the new corporation.”

This hinted at a change in focus for Lebbeus Burton’s old home at Sunnyside: “Under the amended charter, St. Vincent’s Institute will continue Sunnyside in connection with intensive work in the field of child guidance and youth recreation programs . . . It is contemplated that . . . St. Vincent’s Institute of Troy will be able to conduct intensive work in the field of child guidance and youth recreation programs. Consideration, it is said, is being given to the long term plans of the organization. A day camp program for the children of the city has been instituted at Sunnyside. Extensive improvements and repairs are being made to the property there to make it available for such use. The recreational program will be operated for the summer by the Mothers’ Club of St. Patrick’s Church under the direction of the pastor, Father Hunt.”

To this day, there is a child care center at Sunnyside: the Sunnyside Child Development Center of the Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Albany, still in Lebbeus Burton’s old home, still with playgrounds and a swimming pool. The legacy of the fortune made in wholesale drugs, beaver oil, and root beer lives on, 118 years after Burton’s death.

Leave a Reply