There was a time when the organization of the Albany police department was a very hot political issue. That time was 1896. Back in the days when there were two parties in Albany government, the police were often needed in order to keep the minority party from generating too many votes at the polls. The Albany Police Bill of 1896 was an attempt to keep the police out of electoral politics.

The view then was that the Albany police were essentially an extension of the Albany Democratic machine, and that they were being used to round up votes, “encourage” people to go to the polls, and perhaps to discourage others from showing up. This was at a time when there was also a Republican machine; we know that’s now hard to believe, but there were Republicans in Albany then, and somebody had to stop them from voting, so that fell to the police force.

The issue of police being involved in elections was not isolated to Albany, as evidenced by the number of bills introduced around this time to reorganize police forces along bi-partisan, non-partisan, or other-partisan lines. The Troy Daily Times wrote in April 1895 that, when a Republican governor and legislature were elected the previous fall, “nothing was considered more absolutely certain than the enactment of a law that would grant to this city sorely needed relief from the rule of the corrupt and crime-stained Murphy machine.” A bill was drawn up “providing for the creation of a new police force which should be wholly free from the Murphy taint and ring control.” It was charged that police in Albany, Troy and Greenbush “had been used by the Democratic politicians to roll up Democratic majorities in those places. Drastic measures were required to purify these police forces, which had protected and encouraged violations of the election law.” In the Senate, it was introduced and championed by Myer Nussbaum, who represented Albany and had been a police justice at one time. In the Assembly, it was introduced by Albany representative Robert Scherer.

In Albany, as in Troy and elsewhere, it is apparent that the police were used to round up votes and commit election frauds. That led to bills that would establish bi-partisan police commissions, instead of the single-party commissions that prevailed at the time. The Express on Feb. 7, 1896 summarized a hearing in the legislature, saying “All who went before the committee to speak against the bill were compelled to admit that under the police force as it is at present organized, the grossest election outrages were perpetrated. They were forced to confess that the men who were most active in the crooked work that was done at the polls have been retained on the force.” The Evening Journal wrote that the Albany Police Bill “has been denounced and misrepresented by every enemy of decent government and honest elections in Albany and elsewhere in the state.” However, Senator Grady said that the Albany Bi-Partisan Police bill “was drawn by a politician, and not by a statesman,” and said it was designed to put the police force into the hands of Republican boss Billy Barnes.

In the February hearing, a representative of Loudonville, then the eleventh Watervliet district, had to acknowledge that the Albany city police had been used in swaying balloting in that district. Senator Nussbaum, sponsor of the bill, asked “Did not a portion of the police force go into your own town at one time to defeat the will of the electors by making an outrageous attack on the Republican inspectors and seizing the ballot box, in the old eleventh Watervliet district?” The representative, George L. Stedman, admitted that was so, but argued against reorganization of the police force, and “thought most of the men had been removed.” In fact, Senator Nussbaum charged that “every man implicated in the election frauds in which the police were engaged is still a member of the force” in 1896; the response he was given was that if that were true, “it was because no evidence had been placed at the disposal of the police board.”

There was some last-minute tomfoolery, or not, regarding the printing of the bill, which was then in the hands of the state printer, who was John Milholland, publisher of the New York Tribune and in no way an Albanian (though he had worked in Ticonderoga before moving to NYC). In 1895 he somehow won the lucrative state printing contract, without having a way to actually perform it; he intended to sub-contract it to Weed-Parsons Printing Company. To say that Weed-Parsons was connected is beyond understatement; its founder, Thurlow Weed, was a key founder of the Republican Party, and, at this time, Republican leader William “Billy” Barnes Jr. owned the Albany Evening Journal and Morning Express. When Milholland received the contract, he tried to demand $10,000 from Weed-Parsons in order to let them do the work; they were in a great position to refuse and Milholland would have to agree to their terms, but it looks like he found another firm to do the work.

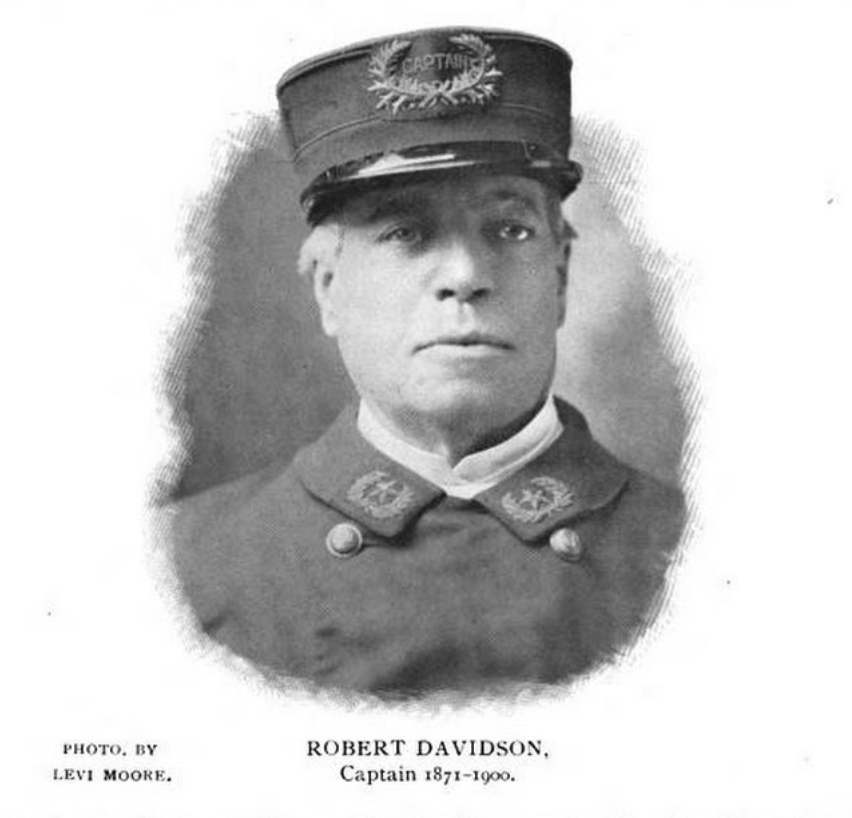

In any case, when the Albany Police Bill, as it was commonly known, was printed in 1896, printed versions in both houses had a typographical error that had the consequence of forcing Captain Robert Davidson out of office, when the actual point of the bill was to keep him in place and to empower him to organize a new police force in the event the bipartisan board was unable to. “The captain has been in the service for a great many years, and he enjoys the confidence of everybody who has the interests of the police department at heart.” The error came from making an independent sentence of the excepting clause, “thereby excluding the proposed exception from the operation of the measure.”

Was that just a typo? The Albany Morning Express, Billy Barnes’s rostrum, didn’t think so. “It was a cunning, subtle trick. No other change could have been made with such few changes of detection.” However, it was caught, and resulted only in delay. “The public printer represents John E. Milholland, boss of the New York Tribune,” the Express wrote, “who is doing all he can to embarrass the Republican party in this state, and who has shown himself especially vindictive towards the Albany county organization. Whether or not this fact explains the mutilation of the Albany police bill, one thing is certain: The state printer has demonstrated his incompetency from the first day of the session. The print of the bills has been marked with delays and errors all along.” In fact, in January 1896, a week’s session of the Legislature was forced to adjourn early because “the public printer could not furnish the printed bills, in compliance with the terms of the contract.”

For his part, Senator Nussbaum argued repeatedly that his bill had bi-partisan support and intent, and that, as the Express told it, it “simply aims to deprive the Democratic machine of the absolute control of elections, which it had held for so many years.” The bill was pretty simple, creating a board of police commissioners – two elected by the members of the Common Council party that receive the most votes in the previous election, two by the party that received the next highest. However, it was also required that those commissioners be members of those parties. It also included some requirements for police officers,

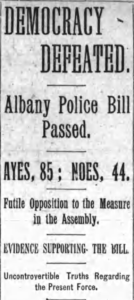

When the bill passed the Assembly the Albany Morning Express shouted: “Democracy Defeated. Albany Police Bill Passed.” That’s confusing to anyone keeping track of the Express’s advocacy for the bill, but they were using “democracy” to mean the Democratic machine, not democracy in its current sense.

A resolution by the Unconditional Republican Club, “the oldest and strongest Republican association in this city and county,” urged Governor Morton to sign the bill. The organization was “fully cognizant of the many election outrages which have been persistently perpetrated upon the electors of this city, and which have been possible only with the well understood acquiescence and organized assistance of the Albany police, when controlled by the representatives of a corrupt political machine, as they were and are now . . . .”

There was drama after the passage, with a threat of a veto from Governor Morton, who asked for and received amendments, including provisions that the commissioners would be selected by, and members of, the two parties that had received the most votes in the most recent election – not necessarily Democrats and Republicans; it allowed for the possible rise of a local third party. The bill then had to go to Mayor Thacher and the Common Council under whatever home rule provisions prevailed at the time. The Republican-led legislature said they would remain in session until the bill was returned by Albany, at some potential expense to the state, and Mayor Thacher, despite being opposed to the bill, said he would return it promptly. He did, but with a “veto,” which apparently required the legislature to revote to override.

Passed and finally signed, the law was quickly taken to court, and the appellate division of the state supreme court found the bill unconstitutional. The reason? The requirement that the commissioners be members of the two parties with the highest representation in the Common Council. As the Times-Union reported it, “an important feature of the constitutional system is that no one shall be affected in any of his political rights by reason of his opinion on political subjects or other matters of individual conscience, and it applies to every privilege conferred upon the citizen by the constitution.” Later that year, in October, the Court of Appeals found it to be unconstitutional, for much the same reasons. “The Legislature of this state has no power to enact a law which proscribes any class of citizens as ineligible to hold public office on account of political belief or party affiliations and consequently the last clause of this section of the law in question violates the constitution and therefore is void.”

It’s fascinating that “The History of the Police Service of Albany from 1609 to 1902” published by the Police Beneficiary Association of Albany, N.Y., makes not a single mention of this multi-year battle to reform the police department. However, the number of “police bills” introduced regarding other municipalities certainly indicates that the politicization of the police was not a problem restricted to Albany. According to the “History of the Police Service,” in 1900 the municipal government became subject to the general laws of the State of New York, repealing the law of 1870 that had established the previous commissioner system and placing the Police Department under a single Commissioner of Public Safety, appointed by the mayor. In general, the new Second Class Cities law (now mostly deprecated) established a better separation of legislative and executive powers, and created a commissioner of public safety in each city, who could appoint a health officer and superintendent of buildings, and could fill a vacancy in the chief police or fire positions. The law also accomplished the goal of the Albany Police Bill, in prohibiting certain political activities and requiring that any officer or member of the police department who violated any provision of Section 17-110 of the Election Law, which barred any commissioner, officer or member of the force from using, threatening, or attempting to use official power or authority in aid of or again any political organization, or to affect the affiliation or opinion or any citizen. It also barred appointments, punishments, etc. within the force based on party affiliation, and barred soliciting or receiving money from any political group. Today, that seems like the minimum we would expect of our police forces, but at the turn of that other century, it was controversial stuff.

Leave a Reply