Paging through an old Schenectady Directory, an oddly worded series of advertisements led us to an interesting story – the story of the armless man who owned a group of rooming houses in Schenectady and once, quite famously, drove across country.

Looking through the 1920 directory, searching for some other bit of history, we noticed these facing-page ads for the Hotel Foster and the Seneca, two iconic downtown edifices for decades. (The Foster recently underwent a wonderful renovation; the Seneca nearly succumbed to a neighboring fire, but has now been restored as well.). It wasn’t the buildings themselves that caught our eye – it was the advertising copy above the pictures:

“WHY SLEEP IN THE PARK WHEN . . . YOU CAN GET FIRST CLASS ROOMS”

It continued on the next pages with advertisements for Bachelor’s Hall and The Livingston:

“WITH UP-TO-DATE CONVENIENCES . . . AND AT REASONABLE PRICES”

Finally, a fifth full-page ad for The Mynderse:

“FROM A.L. STEVENS.”

We can’t be alone in thinking that sleeping in the park, if you could afford a first class room, wasn’t actually an option. Was it?

Stevens had quite a collection of rooms to rent. The Hotel Foster, at 508 State Street, advertised 60 nicely furnished rooms, with a bathroom and separate toilet on each floor. Plus hot and cold water in every room, and an elevator. Rates were $1.50 per day or $6.00 per week and up; more for rooms with a bath.

The Seneca, at 120 Jay Street (“Opposite City Hall – Rooms for Men and Women – Open Day and Night”) featured 47 “light, airy rooms. Newly furnished in Mission style, two bath rooms and separate toilet and lavatory on each floor. Call bell in each room. Use of telephone and other conveniences.” The Seneca would only run you $1.00 a day, or $3.50 a week, and up. (By the way, try to get a 50% discount for a week’s stay at a hotel today.)

Bachelor’s Hall, two minutes’ walk from the new trolley waiting room, at 618 Chapel Street, had 74 rooms for men, with two bath rooms, shower bath and two separate toilets on each floor; lavatory with hot and cold water in each room, at only $3.00 to $7.00 per week.

The Livingston, 773 State Street, was listed as an “excellent location for permanent roomers.” It had 30 rooms and six three-room apartments, all furnished in mission style, with two bathrooms on each floor and use of telephones. Rooms went for $3.75 to $7.50 per week; apartments from $9.00 to $10.50.

The Mynderse, at 785 State Street, was “homelike and quiet.” It had 30 rooms and six three-room apartments, again in Mission style, with two bathrooms on each floor and use of telephones. It ran $3.75 to $7.50 per week for rooms, $9.00 to $10.50 for apartments.

Who was A.L. Stevens?

It made us curious, who was this A.L. Stevens, who owned such a fleet of properties? Apparently Albert Livingston Stevens was a native of Schenectady County, born in 1874, and was orphaned at 10 years of age. In 1888, the 14-year-old was working for the very new Edison works (later a little bit better known as General Electric) when he was, according to the Albany Express of Sept. 23, “struck by a freight train near Darrow & Co.’s coal yard in [Schenectady], yesterday, and terribly injured. He was taken to the free dispensary, where both arms were amputated. The freight engineer was Walter Green, but no blame is attributed to him.” One arm was completely lost; the other was retained to just below the elbow. A 1913 biographical article, when he was running for the position of Fourth Ward supervisor, said that,

“When he recovered his health, notwithstanding his loss of limbs, Mr. Stevens continued his studies in the public schools and at Claverack College. In 1893 he left this city to travel for a theatrical concern, and later became a traveling salesman. In 1901 he returned to the city and opened in co-partnership with Harry E. Webster, a newsroom at State street and Nott Terrace.”

He married a Canadian immigrant named Mabel Brown around 1905. He entered the rooming house business, starting with the Livingston. He followed with the Mynderse and Bachelors’ Hall. In 1912, he leased the Hotel Seneca and put $5,000 into making improvements to the rooms and hallways to make it “one of the most modern rooming houses in this section of the state,” including new Mazda lamps and reflectors, and a system of bells. It would appear his business was very successful, and he was well-known in fourth ward politics.

Stevens made national news in 1915 for doing something you might not expect an armless man to do: he drove across the country, from Schenectady to San Francisco to attend the Panama-Pacific Exposition. The New York Tribune announced it in March 1915:

“Albert L. Stevens, who lost both his arms in a railroad accident twenty-six years ago, will start next June from his home in Schenectady on an automobile trip across the continent to the Panama-Pacific Exposition at San Francisco, driving his own car, a Ford.

“Doing the driving himself will be no experiment for Mr. Stevens. This remarkable man, by grit, determination and natural cleverness, has taught himself to do most of the things that other men do in spite of the fact that his right arm was removed from the shoulder and his left one just below the elbow.

“Some time ago he determined that he could drive a car, and he picked out a Ford. Purchasing his car in April, 1914, by December he had driven it a little more than 10,000 miles. He has made many long tours – one to New York, one to the Thousand Islands and one to Washington. His touring experiences have taken him over all manner of roads, and he has never met with an accident.

“He describes the few necessary alterations he made as follows:

‘I had the emergency brake lever changed so I can operate it with my foot. I have a foot accelerator to feed the gas; electric lights, which I turn on or off with my foot; an electric horn, which I blow by pushing a button with the side of my knee; spark level bent so I can advance or retard the spark with my knee, and I crank the engine with my foot. I have a steel S-shaped attachment which clamps on the side of the steering wheel. I place my arm in that and steer very easily. I drive just as steadily and well as most people with two hands and arms, and, I think, a great deal better than some. I can turn around anywhere and go anywhere any one else can go.’

Mr. Stevens will be accompanied on his across-the-continent trip by his wife and two friends. They will carry a light camping outfit to make themselves independent of hotels.”

If we could ask him one question, it’d be: Why sleep in the park?

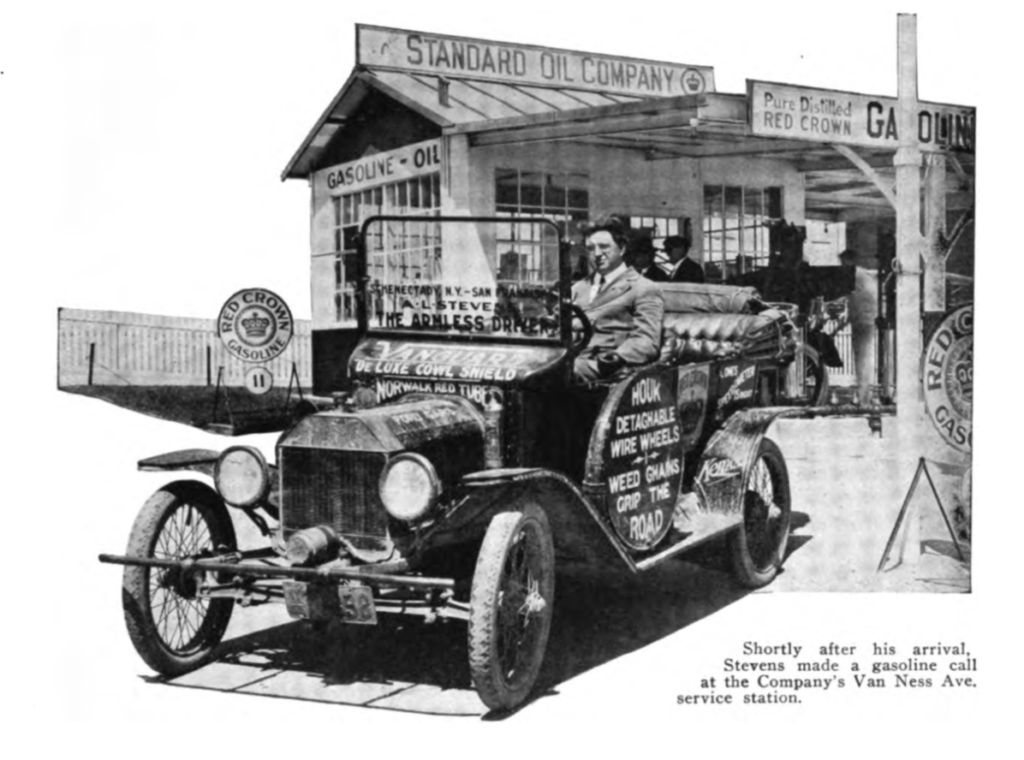

Amazingly, we were able to find this high-resolution photo of Stevens in his Ford, plastered with advertising, including his own. The front right fender reads “When in Schenectady N.Y. Stop at Hotel Foster 508 State St.” Across the windshield reads “Schenectady N.Y. to / San Francisco and Return / A.L. Stevens / The Armless Driver.” The rest of the ads are for Kelly-Springfield tires, K-W Road Smoothers, Norwalk Red Tubes, Dann Inserts, the Vanguard deluxe cowl shield, Houk detachable wire wheels, and Droms Garage on Keyes Avenue, which may well be where this photo was taken. With the sponsorships, Stevens said that he broke even on his trip.

He started on June 8, and made it to San Francisco by July 29 – one has to remember that this was 1915, and there were barely paved roads. Directional signs were few and far between, and the Rota-Ray wouldn’t be invented until 1921. That he had racked up 10,000 miles in just a few months in 1914 seems almost impossible. The Standard Oil Bulletin reported that Stevens gassed up at their service station on Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco. “Being a hotel man it is perhaps natural that Al. Stevens should smile and laugh his way through life. To him it was funny when he concluded that farmers in Nebraska were directing him and other cross-country motorists into mud holes so that they could have the job of hauling them out at $10.00 per car. To him it was funny when a Golden Gate Park policeman ordered him out of the park because San Francisco has regulations against advertising on the park boulevard.”

In 1920, at least Stevens and wife lived at Bachelors’ Hall. We don’t find him much in the news after that. In 1924, he was advertising the entire furnishings of a 48-room hotel (the Seneca?), listing his address as 233 Broadway, opposite Neil Ryan’s Garage. We found him still living in Schenectady, at the Hotel Foster, in 1932. At some point, he moved south, to Southern Pines, North Carolina. He died there in 1963, at the age of 89, and was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery there.

The Seneca and the Foster still stand and, as we noted, have recently been renovated. Of the others, it would appear that only The Livingston, at 773 State Street, still stands.

Leave a Reply