We’ve written before about some of the prisoners of the Albany County Penitentiary, a rather legendary lockup. But the old city jail, on Maiden Lane just behind City Hall, “hosted” one of the most notorious bank robbers of his age, Maximilian Shinburn. It’s a tale of safe-cracking, safe-blowing-up, and possibly of love with a maiden stenographer.

In the same July 22, 1895 edition of the Albany Morning Express that found a bride in the soup, there was a story on a then-current denizen of the old Maiden Lane jail, whom the headline described as “Slickest Robber in America, Is Maximilian Shinburn Whom the Jail Harbors. His Methods Are all His Own. He is a Man of Patience and Strategy; Not of Violence.”

“Maximilian Shinburn or Shinborn, alias ‘Count’ Mark Shinburn, alias H. E. Mosher, now in the Maiden lane jail for his suspected complicity in the attempt to rob the Schoharie bank last spring continues to attract a great deal of attention from visitors to the jail. Shinburn was at the request of the Schoharie authorities placed in the Albany county jail for safe keeping. The criminal record of Shinburn is such that it was deemed best to take no changes with him, but place him in a secure place. Sheriff Thayer has his hands full, the jail at present containing some of the most desperate criminals in this country, and a constant watch day and night is kept in and about the jail.”

Turns out that was not without reason. Shinburn was rather famous. According to “Professional Criminals of America,” an 1895 tome by former New York City Chief of Police Thomas Byrnes, Shinburn was recognized for thirty years by police authorities all over the world as the “King of Bank Burglars.” “He is an American product, in the criminal sense, having begun his ‘professional’ work here early in the sixties as a leader of that great galaxy of safe breaking stars, all of whom are now either dead or imprisoned under virtually life sentences. He fled twenty years ago from this country, carrying away half a million dollars in plunder. It now appears that three years ago he quietly returned to his original field of operations, organized a new band of burglars, and went to work. All of the recent bank robberies in this vicinity are now attributed to the skill and generalship of Shinburn, and a vast amount of evidence is in the hands of authorities indicating that his is the genius which substituted nitro-glycerine for the safe breaking appliances of earlier date.”

He was arrested for robbing the First National Bank at Middleburgh (Schoharie County) with three accomplices on April 16, 1895, “but this is only one of a hundred crimes perpetrated by him during an unparalleled record.” He was arrested by Pinkertons June 28 in New York City and taken to Middleburgh under heavy guard, and apparently from there transferred to Albany for safe keeping, so to speak. In the previous two years, his band of robbers were believed to have robbed banks in Griswold, Iowa, Phoenix, NY, Milan and Sandusky, Ohio, Thomaston, Connecticut, and in Montreal and Toronto.

“Under a dozen aliases and over a period of thirty years he has stolen millions, evaded countless pursuits, broken out of a dozen prisons, lived in luxury, purchased a foreign title, engineered the greatest robberies of the age, and fairly won the title of the century’s greatest thief.” Born in Germany, he first appeared in New York City in 1860, gaining attention as a patron of the best hotels in the city, and as “a gambler of remarkable nerve and seemingly inexhaustible purse.” If a later article is to be believed, he was taught the trade of machinist and locksmith by his father, and had “wonderful skill” as a locksmith. He came to America before he was 17 and embarked on crime before he was 18. He fell in with a rogue’s gallery of rogues and went on a safecracking spree, beginning with a New Jersey bank. “He progressed rapidly,” the Los Angeles Herald later reported,” and as his ability became known in the ‘crook’ world his services were in constant demand.” He soon started organizing his own heists, always through breaking into the safe.

“At that time the only safe in general use in banks and business houses in this country was that made by the Lilly [sic] company. Shinburn figured that a man who could master the Lilly combination lock could loot every Lilly safe in the country.” So, he did what any clever criminal machinist locksmith would do – he went to work for Lillie (which was consistently misspelled in the sources).

“It took him over a year to obtain all the knowledge he needed for the successful consummation of the series of robberies he had planned, but he kept at work with patience. The most important discovery he made at the time was that a person with acute hearing could, by putting his ear near the lock of a Lilly safe and turning the dial, discover at what numbers the tumblers dropped into placed. He made a careful study of difficult combinations, and is credited with a discovery that is alleged to have driven the Lilly safe out of the market. He removed the combination from a safe and then placed an impressionable piece of paper under it. Then he turned the dial slowly and found that whenever a combination number was reached the impression on the paper became more distinct. By using a microscope Shinburn was able to tell what the combination numbers were. With this mass of valuable information Shinburn and his associates plundered Lilly safes all over the country, finally driving the Lilly company out of business.”

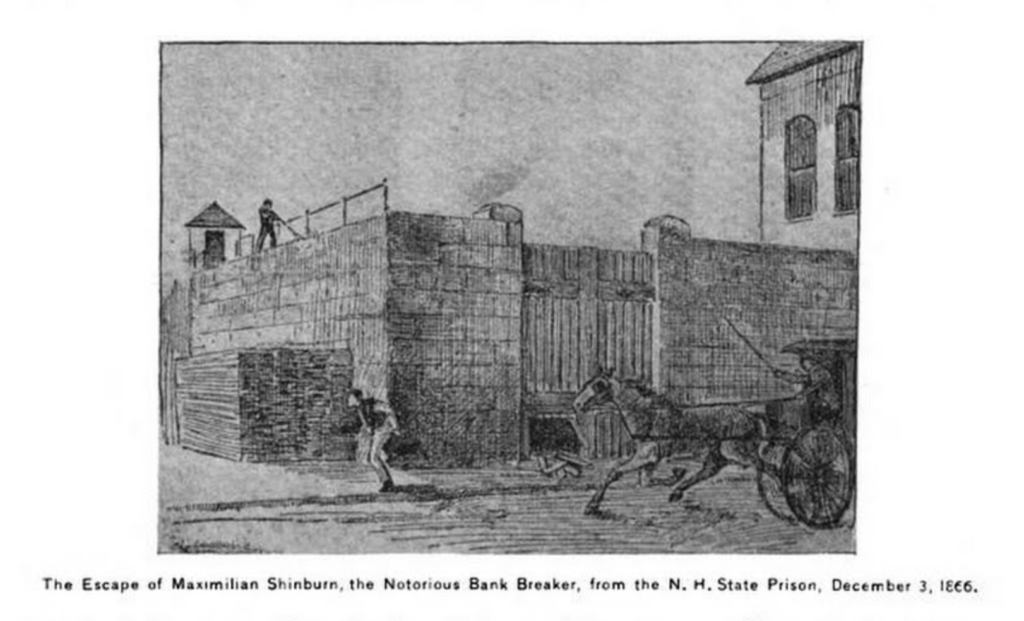

He was arrested in Saratoga in July 1865 for a robbery in New Hampshire, and sentenced to 10 years in that state’s prison but escaped on the first night (you can read about it here) and wasn’t recaptured until 1868, making an attempt on a bank in St. Albans, Vermont. For that he served nine months and escaped. He robbed a coal company in 1867, was arrested and handcuffed to a detective but escaped while his captor slept. There were more robberies, more arrests, more escapes. He apparently invested in the stock market, made a killing, and sailed for Belgium, where he lived large in Europe for fifteen years until he was penniless again. In Paris, he met some American crooks, planned a robbery in Belgium, got caught and jailed . . . and escaped. He returned to the US and began the spree that would see him arrested for the Middleburgh robbery.

Very well known by the time he was held in the Maiden Lane jail, Shinburn seemed to have impressed the Albany Morning Express:

“Even a casual observer at the little window or peek hole, will at once pick Shinburn out from 30 or 40 other prisoners. He dresses neatly, always wear a clean white shirt and goes about in his shirt sleeves. He keeps his hat on and remains most of the time in the rear portion of the corridor. He watches closely all that goes on, but at the same time manifests no interest in transpiring events. The officers at the jail, however, know his record pretty well and there is no time at which his movements are not watched.”

The newspaper goes on to quote “The Illustrated American,” which implicated Shinburn in “the Ocean bank wreck in New York city in 1869 when the bank was almost literally blown to pieces with dynamite. He is looked upon as the most dangerous bank robber, with one exception, who ever operated in America. His methods, however, are less violent than those employed by Hope. He resorts to strategy, watches his chances and as a rule has left little or no clue for the police. One of his tricks has been by some means to get possession of the keys of the bank or discover the combination of its safes or vaults.” He would get keys, make wax impressions, and return at a later time with a false key – then get into the vault to perform his impressionable paper trick, which would reveal the combination to him, though how he was able to slide paper behind the dials of the combination locks and have it remain unnoticed is not explained.

Despite the supposed security of the Albany jail, Shinburn did try to escape. In December 1895 he tried to slip out the cell door after asking the sheriff to give him a cup of water. He was grabbed by the sheriff’s wife at the outer door. “The sheriff’s wife is quite a large woman and the sheriff quite a good man, but Shinburn dragged them both about 100 feet, where all three fell over an iron fence. Mrs. Loveland’s cries were heard at this time and several men from the hotel ran to the scene. Shinburn, when he saw help coming, immediately gave himself up and was taken back to jail. The sheriff supposed that the cell door was locked, but Shinburn must have sawed off the lock during the afternoon, as the sheriff thought he heard a squeaking in the jail, but imagined it was the bed in the cell.” On a later occasion, being transported to Schoharie, Shinburn got into a fight and kicked Sheriff Loveland in the face.

An article from the Atlanta Georgian in 1913 claims that Shinburn found something like love while biding his time on Maiden Lane.

“Once when he was in jail at Albany, N.Y., awaiting trial for the robbery of a bank at Middleburgh, he won the heart of a young woman stenographer, whose desk in the county clerk’s office was directly opposite his cell window. So ardent was the flirtation which Shinburn carried on across the street which separated the two that the girl became infatuated. There followed a long period of correspondence, notes being exchanged by means of a long cord which the prisoner let fall to his waiting sweetheart in the street below.

“Shinburn finally got the girl’s promise to wait for him outside the door leading from the jail yard at 5 o’clock on a certain afternoon. She was to bring with her a loaded revolver and some money.

“Just before the hour set Shinburn got the door of his cell open by sawing off the lock. He cautiously made his way along the corridor, armed himself with a heavy broom handle and waited in a dark corner for the keeper who carried the key to the outer door.

“As the keeper approached Shinburn gripped his club tightly in both hands and swung it high above his head to strike a blow that would have been murder.

“But as Shinburn raised his weapon the keeper saw the shadow of it on the floor. He was a quick man with his revolver, and before the prisoner could strike he turned abruptly and fired. Shinburn fell, writhing in pain from an ugly wound in his leg.

“The love-sick maiden was waiting outside as Shinburn had told her but she fled in dismay when she heard the revolver shot and the cries of pain that followed. Her friends prevented her attempting to communicate with the prisoner again.”

An Evening Journal article from April 13, 1896, does indicate that there was an escape attempt, and that a jailer named McClellan shot at him, but did not hit him. In this version of the story, Shinburn had managed to plug two locks on doors, including using an iron poker and fire shovel (which you might think they’d keep out of the hands of prisoners). In driving him away from the door, McClellan shot at his feet. “I did not hit him. I only wanted to frighten him. He is not hurt.” No maiden stenographer is mentioned.

Byrnes predicted that with this arrest and imprisonment in Albany, his career was over. He remained in Albany until May 1896, when he was tried in Schoharie and sentenced to four years and eight months at Dannemora. After 11 months in Albany, He was taken to Dannemora May 19, 1896: “The prisoner was well dressed and gave his attendants no trouble.” Somewhere along the line, he was granted a retrial, and returned to the Maiden Lane jail in March 1898 on the way to Schoharie.

“When the ‘Count’ entered the office he glanced about him, but the faces he saw were new with the exception of Jailor Collopy, who also held the same position under former Sheriff Thayer, when the ‘Count’ had been his guest for eleven months before his trial and conviction at Schoharie. The ‘Count’ did not speak to the jailer, but gave him a scowl. He was not very friendly to Collopy, who held him to the strict discipline of the mail. The ‘Count’ looked exceedingly well. His hair has grown very grey, and he has gained thirty-five pounds. He wore a prison made suit, a standing collar, polka dot necktie and a black Fedora hat.” He was again convicted, sentenced to three years and one month, and did another night at Maiden Lane before returning to Dannemora.

He appears to have actually served his term; a 1900 Troy Daily Times article says that he left Dannemora on Oct. 10, 1900, having served a term of three years and one month. “When Shinburn stepped up to the clerk’s office his belongings were handed to him and he shook hands and bade good-bye to his keepers. For about thirty seconds he was a free man. Then Sheriff Cunningham of Plattsburgh, Clinton County, armed with warrants, requisitions and legal papers, stepped up and rearrested him on the charge of breaking out of the state prison in Concord, N.H., in 1866, thirty-four years ago.” His eventual defense in that case: that he wasn’t the guy who broke out of prison. He claimed to be Henry Edward Moebus. He didn’t win, and was sent back to the state prison at Concord, but continued to protest a case of mistaken identity. He was freed from Concord in 1908, and according to an article datelined Boston, April 22, “The aged robber enjoyed barely 24 hours of liberty after serving eight years in the New Hampshire state prison before he was arrested on the charge of stealing $200. He protested his innocence.” He was alleged to have taken the money from another man in the lodging house where he was to stay. After that, we lose track of him.

An article in the Los Angeles Herald in 1902 said:

“One of the best living illustrations of the old school of crooks is Maximilian Schoenbein, better known to the police of the world as ‘Count’ Max Shinburn. After defying the vault and safe makers of the world and looting banks in this country and abroad for an aggregate gain of $5,000,000, this great criminal fell victim to modern science. He was released not long ago from the Clinton, N.Y. prison, after a five years’ term for robbing the Middleburgh bank, penniless, gray with age, broken in health and spirit.”

Leave a Reply