Did ya think we were done with the Albany piano makers? Not quite. For one thing, there were quite a lot more – various offshoots and apprentices going off on their own from the established makers that kept Albany a vital pianomaking center for decades. And there was another huge piano maker that we haven’t really touched on yet – William McCammon, maker of McCammon Piano-Fortes. But also, maker of Boardman & Gray piano-fortes. Or maybe not – it was a matter of some dispute.

William McCammon (born 1811) was the son of Enoch McCammon and Lydia Sturtevant. One of their other children, William’s sister, was Elizabeth McCammon (born 1826) – who married prominent Albany pianomaker James A. Gray (born 1815). William and James were pretty much contemporaries while Elizabeth was many years younger. Elizabeth died quite young, following childbirth, in 1853. So, however briefly, William and James were brothers-in-law.

McCammon’s history is a little difficult to figure out. He doesn’t show up in earlier chronicles of piano making, though it’s entirely possible he was employed in some fashion by Boardman & Gray. It’s also possible that he simply entered the business when opportunity presented itself, as it did when Boardman & Gray’s factory burned in 1860. For a few years after the fire, the city directories are very, very confusing about who was doing business at the site at Broadway and North Ferry – whether it was Boardman & Gray, James A. Gray & Co., or the new McCammon Piano-Forte Co. The answer seems to be: yes. More details to follow.

As we have noted in an overly extensive history, Boardman & Gray began building pianos in 1837. They moved all over the place, but for many years were in a factory at Broadway and North Ferry; that factory had a major fire in 1860, mostly destroying the building and a very significant amount of their stock and materials. They did rebuild at the site – or perhaps it was William McCammon who did the rebuilding. A number of articles, including one in the Times-Union from 1881, say that Boardman and Gray sold out to William McCammon in 1862. But both William Boardman and James Gray continued to be listed as piano makers in the city directory, or had their business location listed as Broadway and North Ferry. It now appears to us that after the fire, William McCammon took over the business of building pianos, specifically the Boardman & Gray brand, at the same location, and that he employed James Gray and William Boardman in that endeavor. Perhaps given the devastation of the fire, this was the only way that the venerable piano makers could continue. But it wasn’t a relationship that lasted long.

Feud with Boardman & Gray

Through a series of opposing “notices” in the Albany Evening Journal, usually printed one just above the other, we learn of a business relationship that went seriously sour. In one Boardman and Gray acknowledge that they “disposed” of their piano-forte factory to William McCammon in 1862, “having arranged that we should remain and supervise the business.” In furtherance of that, they issued what they called a “card” that said that they “would respectfully solicit for him the favorable consideration of our friends, as we are satisfied that the character of the instruments will be fully sustained.” The card said that “Messrs. Boardman & Gray, of the late firm, are engaged, and will give their undivided attention to the manufacture of the Pianos. The public will therefore be assured that the article sold will be in every respect the same as that heretofore made by them.”

As we said, that didn’t last terribly long. It looks like McCammon discharged Boardman at the end of 1864, but the business with James Gray and son William continued. But at the beginning of 1867, both Grays and Boardman published a notice that,

“Having terminated our business connection with the said Wm. McCammon, and the consideration for issuing said Card having ceased, in a letter to him dated Dec. 22d, 1867, we informed him that we had resumed the use of our names in the manufacture of Piano-Fortes, and formally withdrew from him the use of said Card, and all commendatory letters of Piano-Fortes manufactured by us, the originals of which letters are now and always have been in our possession, and forbade him, and all other unauthorized persons using our names in any manner whatever.”

They further noted that his claim to the use of the Boardman & Gray Patented Iron Rim was rather a sham, as the patent, which Gray sold to McCammon for $1, had been declared void by the patent office. “Our successors, Messrs. Jas. A. Gray & Co., do not use it, and do not intent to use it, having invented improvements in the Piano-Forte which entirely supercede it.”

In a counter notice, McCammon posted his Dec. 31, 1864 letter to William Boardman, which simply said, “Dear Sir – After the above date, compensation for your services will cease.” He explained that the public would see the “impropriety” of Boardman “giving the impression that he withdrew from my employ of his own free will.” He goes on to say that since Boardman is not a partner in Jas. A. Gray & Co., “it is difficult to imagine any motive other than personal hostility to me, which should prompt Wm. G. Boardman, of Buffalo, engaged in the Lithography business, and having no connection with the firm of Jas. A. Gray & Co., to intermeddle in a matter with which he has really no concern.”

A year later, in January 1868, the feud was ongoing. Gray posted this notice in the Evening Journal:

Boardman, Gray & Co.,

New and Improved

Piano-Fortes

Notice.

For some thirty years past, the undersigned has associated with the late firms of Boardman & Gray, and Boardman, Gray & Co., of this city. In the manufacture and sale of their celebrated Piano-Fortes, and having ceased his business connection with said firms, does hereby assign over to James A. Gray, his former partner, and the only practical Piano-Forte maker of said firm, his entire interest to the exclusive right and good will of said firms to the manufacture and sale of the Boardman, Gray & Co. Piano-Forte.

Mr. James A. Gray having associated with him in business his brother, W. N. Gray, in the manufacture of the Boardman, Gray & Co. Piano-Fortes, introducing new and improved scales and designs. I do hereby cheerfully commend them to the public as worthy of their patronage, as the utmost confidence may be placed in the superiority and durability of their instruments.

Albany, N.Y., Oct. 18th, 1867. Wm. G. Boardman

The undersigned are now manufacturing Piano-Fortes with

NEW AND IMPROVED SCALES

And are determined to maintain the high character for their instruments which Boardman, Gray & Co. so long enjoyed.

JAMES A. GRAY & CO., (Successors to Boardman, Gray & Co.,) Manufactory and Warerooms, 175 North Pearl street, Albany, N.Y.

Immediately below that, McCammon ran a counter-notice stating that Boardman, Gray & Co. had sold their factory, stock and materials, and that James A. Gray assigned to William McCammon, for the sum of one dollar, a patent for an improvement in piano-fortes from May 1, 1860. He then proclaimed that Wm. McCammon & Co. were manufacturers of the American Piano-Fortes, and sole manufacturers of the Boardman & Gray Iron Rim Piano-Fortes. (That the patent had been invalidated, he chose not to address.)

In November 1868, the feud continued, as James A. Gray once again published a notice to the editors of the Evening Journal:

“We notice a communication in your issue of yesterday, from certain parties styling themselves, ‘Sole Manufacturers of the Boardman and Gray Piano Fortes.’ In order to prevent the Public from being misled or imposed upon, we beg to give notice that we are the only persons authorized to use the name of Boardman and Gray in the manufacture and sale of Piano Fortes.”

Immediately below that was a notice from McCammon, claiming to be sole manufacturer of Boardman & Gray Piano Fortes, which also referenced a dispute over his claim to have won prizes at the Rensselaer County fair, beating out Steinway; the hosts of the Fair, the Rensselaer County Agricultural Society, said otherwise.

We lose track of the dispute beyond that point, but both companies continued to grow and prosper. (There are a number of piano-related websites with incorrect timelines and histories of the relationship between Boardman and Gray and McCammon; we believe we have here represented it correctly, from original sources.)

The Factory and Store

An 1875 publication, “Asher & Adams New Columbian Rail road Atlas and Pictorial Album of American Industry,” says that

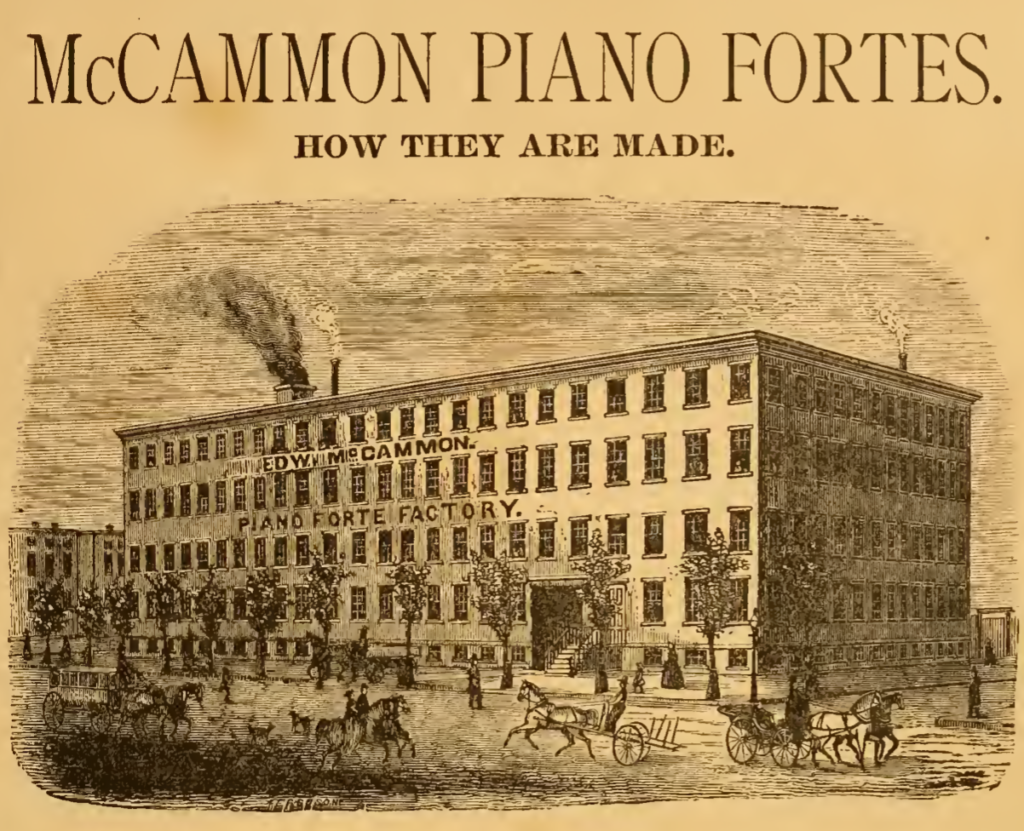

“Among the oldest and most favorably known piano-forte manufactories in the United States is that of Mr. Wm. McCammon of Albany. N.Y. This house was founded about forty years ago by Messrs. Boardman & Gray, who were succeeded in 1862 by the present proprietor. The accumulated experience of so many years, and a successful effort to profit by every new development in the art, the pianos of this house have gradually yet constantly increased in favor and popularity until they now stand in the first rank of distinction in every respect, among those most competent to judge. This extensive establishment is one of the largest and most complete in its appointments in the United States. It is a brick structure, five stories high, and divided into five fire-proof compartments, secured by iron doors. The building is 175 feet front, with a wing 100 feet long, the whole containing 36,750 square feet of floor. The building is on three streets, and with the lumber yard, covers a space of 26,250 square feet. The entire establishment is heated by steam, which passes through over two miles of pipe, fed by an engine of one hundred horse power. A magnificent engine of forty horse power propels an almost endless variety of new machinery, of the most approved designs.

“An immense quantity of all kinds of lumber required for the construction of Piano-Fortes is constantly piled in the lumber yard, exposed to all kinds of weather, from six months to two years, after which it is put into three extensive drying rooms, which are heated by steam and capable of holding 150,000 feet of lumber, where it is kept from six months to two years longer. Contracts for lumber are made annually, with the parties who cut it, thus giving the purchasers the advantage of first prices.

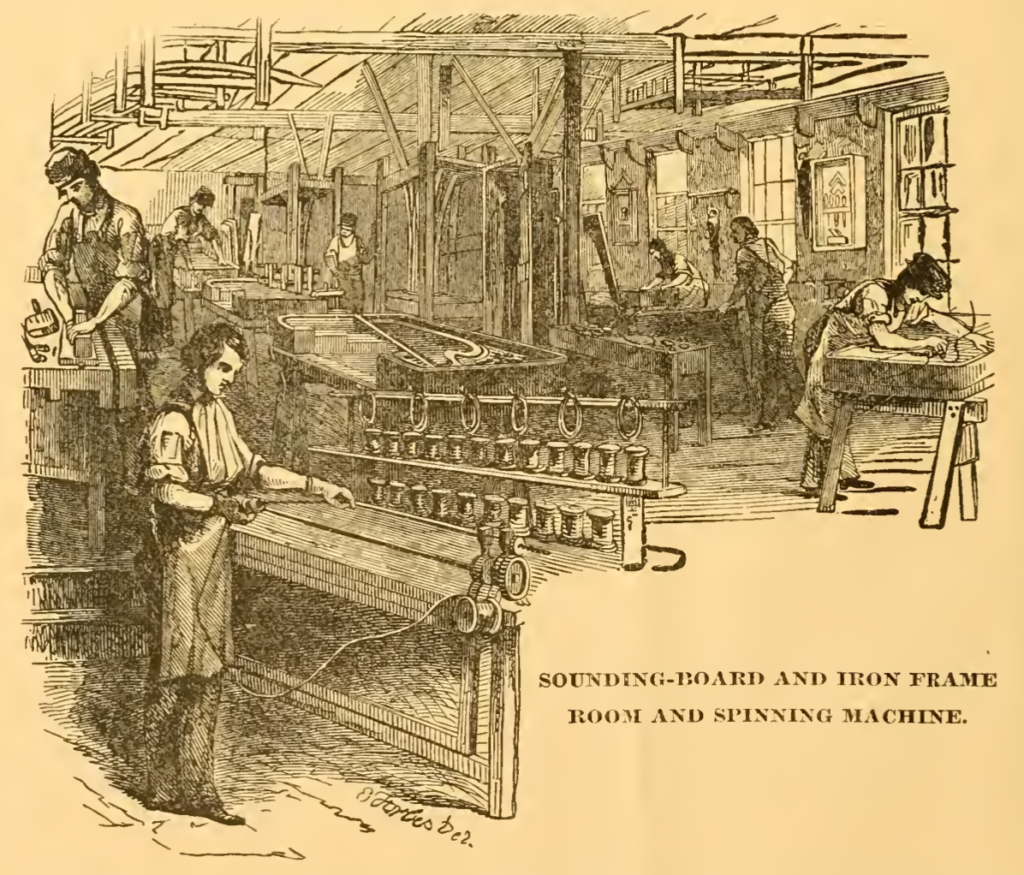

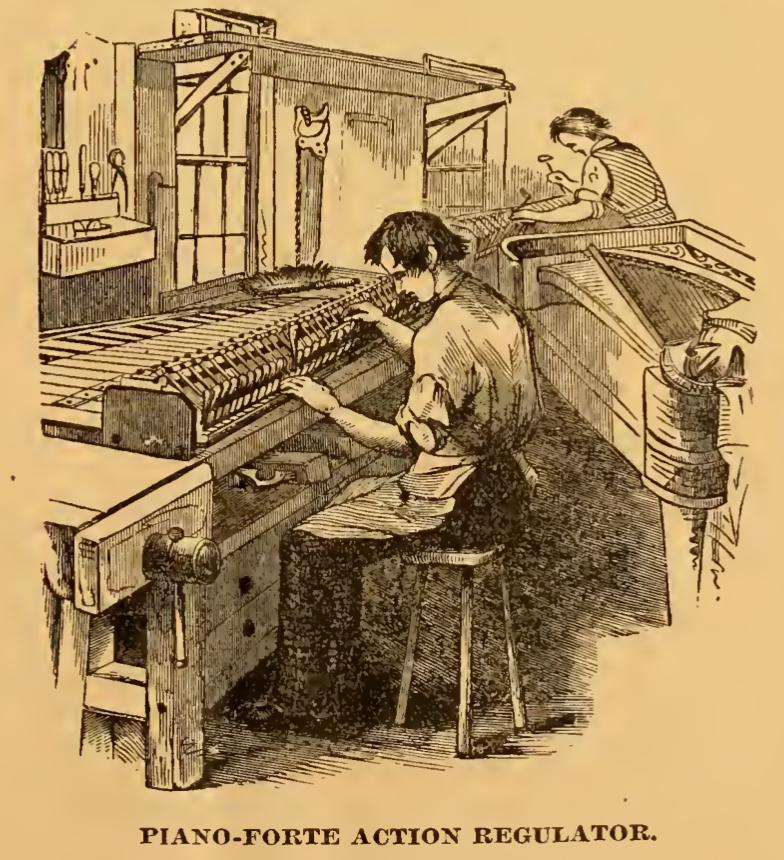

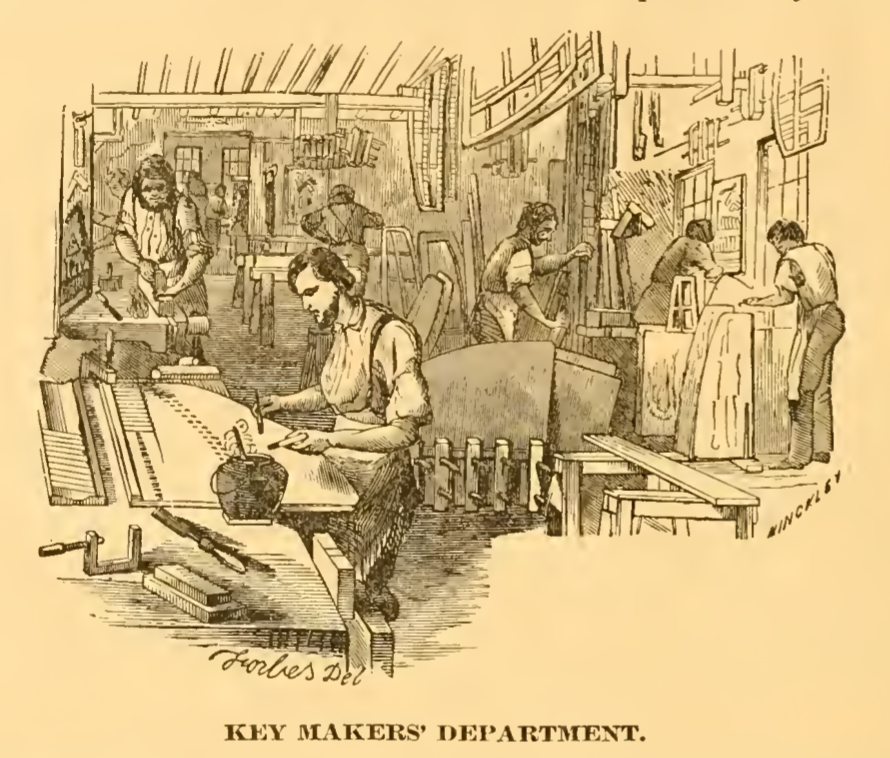

“The basement of the building is devoted to the manufacture of iron work. The first floor is occupied by the regulators and tuners. The packing room and machine shop are also on this floor. The second floor is devoted to the fly finishers and case makers; the third floor to finishers, carvers, sound board makers, &c.; and the upper part of the building to the varnishers, polishers and rubbers. He [sic] occupies elegant warerooms including two floors, on broadway. No piano is allowed to leave the factory until it is thoroughly examined by the superintendent, and known to be perfect.

“When we consider that the number of pieces in a piano is about 20,000 we may be able to appreciate in some measure the value of a perfect piano. Few persons we apprehend, as they look upon a piano, or listen to its enchanting music, consider the vast amount of labor, the perfection of material and the superior mechanism, requisite for the construction of such an instrument. The great number of workmen required in the construction of a piano, and the great variety of woods essential to impart the requisite properties to the different portions of the instrument, require, as may be imagined, the exercise of the greatest judgment, to secure such pieces, and so combine them, that they will produce that harmony of action and its results—sound—toward which all should tend. It is indispensable that these pieces be securely and proportionately adjusted to each other in the massing together of all the parts. The slightest vibration in any part desired to be fixed, or immobility in any part intended to vibrate, mars the effect of the most perfect perform, and often renders the player an object of deserved sympathy.

“This establishment has now turned out about 11,000 pianos of superior merit as is attested by testimonials of many of the best artists; among whom are Thalberg, Gottschalk, Jenny Lind, Jules Benedict, Strakosch, and Charles Halle.”

Edward McCammon takes over

In 1877, William was succeeded by son Edward McCammon, who expanded the company’s retail presence into Tweddle Hall. The Times-Union wrote it up:

“Hitherto Mr. McCammon’s retail trade has been confined to the factory on Broadway corner of North Ferry street, but the business has so increased that the establishment of a branch retail store became necessary. A large store one hundred feet deep by twenty-five wide in Tweddle hall, and known as 81 State street, has been elegantly fitted up for this purpose, and was last night formally opened in the presence of a number of members of the press and of the musical profession, who passed a very pleasant and social evening together in examining the appointments of the store and listening to some excellent music. . . . The new establishment will be under the general superintendence of Prof. George N. Rockwell, the organist of the Lutheran church, and Mr. Edward J. Flynn, who will have charge of the sheet-music department, having hitherto been employed in the same capacity at the upper store . . . particular attention will be given to sheet music which Mr. McCammon, through his special facilities, is enabled to sell at half price, the music comprising all the American and European publications.

“There are but three piano factories in the country which make every part of an instrument, and Mr. McCammon’s is one of them. His factory turns out a piano every four hours, or about a thousand a year, a number greater than that of all the piano factories in the United States west of Albany, combined. About 125 men are constantly employed, and such is the demand for these pianos that it is almost impossible to fill the orders that come from every part of the country. These pianos range in price from $500 to $1,000. Some idea of the continued increase of the business can be obtained from the fact that during the last four years the number of pianos made by this one firm has increased at the rate of a hundred a year.”

William McCammon died in 1881, just a few years after giving the business to Edward. Perhaps not coincidentally, McCammon ads no longer make any mention of the Boardman & Gray brand after that time.

In 1883, Edward McCammon’s music store in Tweddle Hall became, briefly, very very famous, as the origin of the fire that destroyed Tweddle Hall. After that their retail location seems to have moved to 53 North Pearl, and the factory continued at Broadway and North Ferry. Boardman and Gray and McCammon seem to have managed to coexist after that time without further friction. But business seems not to have continued to go well for McCammon. In 1887, Edward McCammon bought his own factory at a foreclosure, when one of three mortgagors on the property took action against him. That saved the business for a while, but in 1891, another creditor took action and the company was put into receivership. The factory itself was auctioned off in January 1891, and the debts and remaining property was disposed of around September 1891. How he did it, we don’t know, but somehow Edward picked himself up, moved to Oneonta, and started a new piano factory. (Sites that date the Oneonta factory to William or even earlier are, quite simply wrong.) The Oneonta Daily Star’s website includes the following:

After its first full year in business in Oneonta, the McCammon Piano Co. held its first annual meeting on Jan. 9, 1893, and as The Oneonta Star reported the next day, “The business of the company has been most excellent the past year and reflects credit upon all concerned.”

“This company is a strong combination, equipped with an elegant plant, having strong financial backing, and are putting on the market a piano second to none. They have run full ten hours every day (except a couple of months in the summer when they ran 12 hours), and have never been able to catch up with their orders since the business was removed … from Albany. It is the intention of the company to materially increase their output the coming year.”

McCammon remained in Oneonta until 1899, according to the Daily Star.

There’s one other bit of weirdness in the intertwined fortunes of Boardman & Gray and McCammon. For many years, James A. Gray lived at 45 Ten Broeck. He later moved to 99 Ten Broeck, then 6 First Street. Near the end of his run in Albany, Edward McCammon, son of James’s brother-in-law William, lived at . . . 45 Ten Broeck.

A very detailed but unfortunately undated catalogue from McCammon survives: “McCammon Piano Fortes How They Are Made.” It is VERY detailed, and gives a thorough description of the factory and its operations.

Leave a Reply