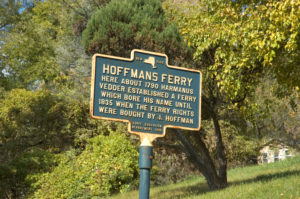

We posted this marker for Hoffmans on our Instagram account (@signsandmarkers) a little while back. Hoffmans is one of those places that, during our lifetime, always used to be a place, a name from history that probably couldn’t have been identified as anything, not even a hamlet, were it not for this historical marker. But at one time, it was an important connection point for Glenville.

Glenville historian Percy Van Epps, to whom we owe a debt of gratitude for this series of posts, noted that the first settler to come to the vicinity of Hoffmans was Karel Haensen Toll, sometime around 1700, until 1712. His holdings were transferred to his son-in-law, Johannes Van Eps, who established a home near Hoffmans in 1721. He built a sawmill there, and his son built cement kilns and a mill. It was here that late in the 18th century the Church of the Woestina, simply Dutch for wilderness, was established.

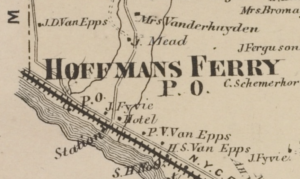

Van Epps says that it was Harmanus Vedder who established the ferry service across the Mohawk. Vedder lived on the other side, in what is now Pattersonville. The service, and Van Epps doesn’t describe the mechanics of it, was known as Vedders Ferry until 1835, when it was sold to John Hoffman, and the little hamlet in Glenville became known as Hoffmans Ferry, “thus often called today, though the official name of its post office is simply, Hoffmans.” In fact, an 1889 Bullinger’s Postal and Shipping Guide identifies Hoffmans Ferry as the central railroad stop for Glenville. A postal history indicates that it was a post office from 1838-1892, and just as Hoffmans from 1892 to 1975.

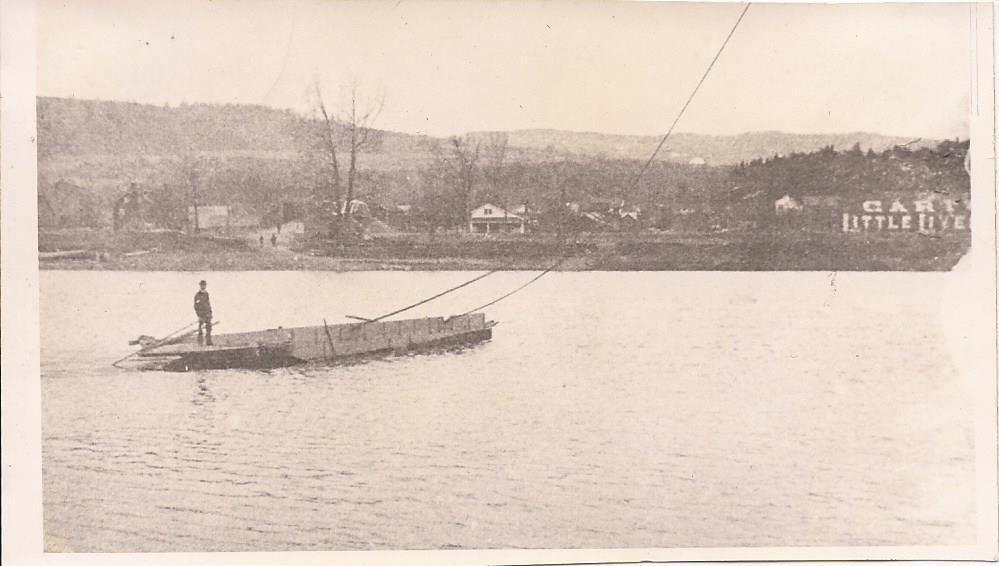

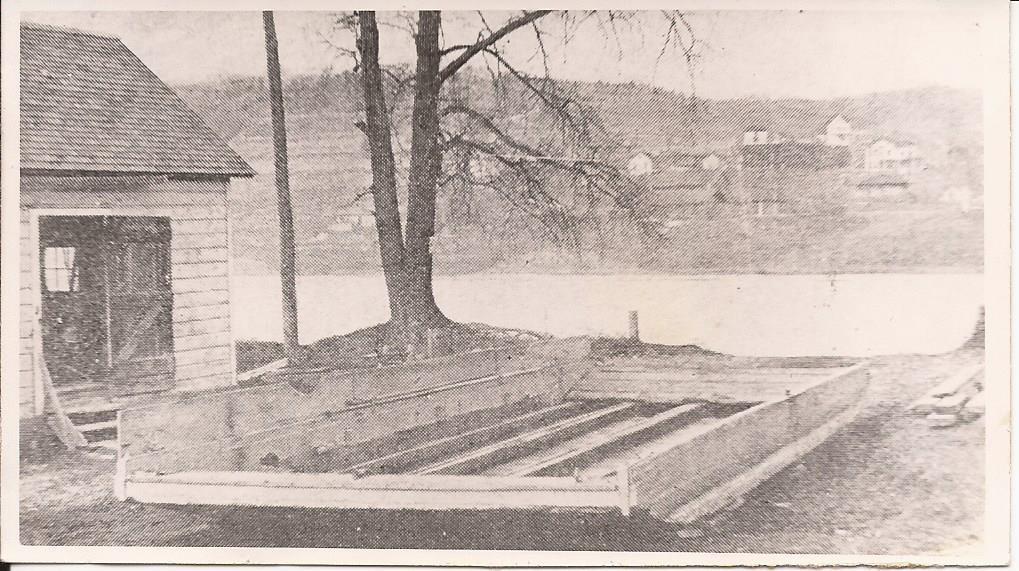

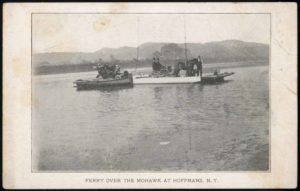

Van Epps says that he doesn’t know whether John Hoffman ever actually operated the ferry or just leased it out. We know that at some point it was operated by John French, and then his son Alonzo French, and then by men named Vander Heyden, Bradshaw, and McKee. The last operator was Louis Phillips. It’s not entirely clear what the earlier ferry technologies were, but Van Epps provides a description of the Phillips enterprise that lasted until 1924:

“Teams and automobiles were taken across on a large scow held on its course by ropes heading to a steel cable stretched across the river, its ends fastened to stout anchor frames on each side. The movement of the scow across the water was effected by adjusting the holding ropes, leading to the suspended cable, in such a manner as to cause the scow to move by the force of the current to either side desired. In its last few years of operation the scow was hastened on its passage to and fro by the aid of a small gasoline motor-boat fastened to its side. The abandonment of this ferry service closely followed the flooring for vehicular traffic of the movable-dam bridge at Lock Nine, two miles below, the first of these ponderous structures crossing the Mohawk River to be thus floored. The accomplishment of this beneficial project was mainly brought about by the persistent efforts of Dr. A.P. Squire of Rotterdam Junction, despite vigorous and ill-directed opposition.”

It’s hard to imagine that this little not-a-dot on the map was once a bustling little center, but it was. In 1836, the Utica and Schenectady Railroad, first in the Mohawk Valley, was completed, and the first train passed through Hoffmans on August 1st. Van Epps writes (in 1936) that the first station stood on the north side of the tracks, “across from the present station and a little to the east.” Meaning there was still a station of some sort in 1936; unfortunately, we have not come across any evidence as to when it went away.

“Before the 1860s this was abandoned and an old white dwelling house standing on the site of the present station was made the stopping place for the trains. The writer well remembers seeing the old station building, a long and high structure, then used for storage of wood for the locomotives. Still, high on its side, facing the racks, above a row of large arched openings, were the words, painted in staring black letters, RAILROAD STATION. At each end of the building was great piles of cordwood. At one end, a steam engine busy sawing the four-foot sticks in half for the locomotives, while at the other end of the old station a tread-power with its team of horses was doing similar work. Coal did not come in general use as a fuel for locomotives until after 1868.” Not only fuel but water was taken on at Hoffmans, and there was a pumping operation that took water from a spring and then from the Compaanen Kill about a mile west. A 1945 “who remembers” article in the paper asked who remember “when a string of 200 canal horses and mules was sent to winter quarters at Hoffmans Ferry? The business proved quite a bonanza to the farmers, who received $1 per head per week for the care of the animals.”

Percy Van Epps

In the early days, railroads were limited in what they were allowed to carry. At first, it was passengers and their baggage only. In 1837, the mail was allowed to be carried. In 1844, freight was allowed, but only in the winter, after the Erie Canal had closed. In 1847, that was expanded to year-round, with railroads paying the same tolls to the state as the canal.

In the 1860s, there were six trains a day at Hoffmans, “a passenger train each way, morning and evening, and at noon a mixed train, a string, long or short, of freight cars with one or two passenger coaches appended. This accommodation train, as it was called, stopped at Hoffmans to discharge passengers, and on signal to take them on. The signals thus used were globe-shaped affairs of basket work painted bright red, which were drawn to the top of tall poles standing on either side of the tracks, as the occasion demanded. At the crossing, the roadway leading to the station, and the ferry, a sign suspended high across the road for years warned the public to LOOK OUT FOR THE CARS WHEN THE BELL RINGS.”

Van Epps tells us that the first station master may have been Michael Carroll, who was followed by Alonzo French (yes, the ferry operator), who held the position for 33 years, and “was absent from duty but two or three days, and never once was he away from his work overnight.” In addition to what Van Epps speculates may have been a record for service on the New York Central, French was also the freight and express agent, and post master of Hoffmans. The son of John J. and Rachel French, he was born in “the old red house that stood near the ferry landing opposite Hoffmans – a landmark of the vicinity for generations. In his younger days Mr. French was employed for some little time on a fast packet boat on the Erie Canal. Later, eh entered the employ of the Utica and Schenectady Railroad as a brakeman. In this service he was caught between two freight-cars and severely injured.”

Super special thanks to Dean Splittgerber for hepping us to this fantastic Life Magazine photograph of Hoffmans by Alfred Eisenstaedt from 1943. The caption is “Signalman Nick Carter watching oncoming train from his signal tower at station on the New York Central’s Mohawk Division. Hoffmans, NY, US 1943 Photographer: Alfred Eisenstaedt.”

The first postmaster of Hoffmans was probably John A. Johnson, who ran the post office in his house, which Van Epps said was (again, 1936) the last one westward between the railroad and the river. It was also a small general store, and at the time Van Epps was writing, the oldest edifice in Hoffmans. After that, French kept the post office in the old station house; when that burned, it moved into the hotel and store that were north of the Mohawk Turnpike. “The present postmaster is Frank Splittgerber, proprietor of a large modern general store which stands nearly on the site of Hoffman’s old hotel.” There had been a hotel going back to when it was still called Vedders Ferry; the last was run by Jack Kellerhouse and his family until it burned in 1918.

“Formerly, before the advent of the automobile, the hosrseless era – great quantities of baled hay and straw were shipped from Hoffmans. Indeed, it was said that this station was the greatest shipping point for these products save one along the whole line of the New York Central railroad. It was not an uncommon occurrence for 200 sleigh loads of hay to be brought here in a single day.”

Van Epps then adds that a flourishing industry in 1936 was the “extensive greenhouses conducted by the Hatcher family.” It was in the 1950s owned by an Alfred Parillo, but we only find references to it through about 1955. More on that business another day.

Today, there is virtually nothing at Hoffmans. From the sky, on the other side of the tracks, one can see what could be the remains of a station, and possibly the old foundation of another; they could just as well be something else.

By the way, the old folks in our family, and everyone else I can remember in Glenville, pronounced it “Huffmans.”

Leave a Reply