Where else do you get a triple threat, two NYS Education Department historical markers and a monumental plaque, and with it the story of an ambush and a corpse tethered to a crow?

The first:

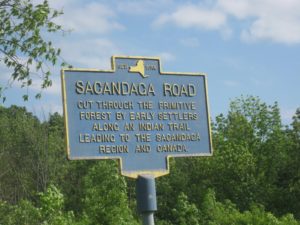

SACANDAGA ROAD

CUT THROUGH THE PRIMITIVE

FOREST BY EARLY SETTLERS,

ALONG AN INDIAN TRAIL

LEADING TO THE SACANDAGA

REGION AND CANADA

Here’s what Glenville’s first town historian, Percy Van Epps, had to say about this marker – which, after all, he selected and wrote. In fact, there were two of these – one at Beukendaal, the other at the point Sacandaga Road leaves Glenville for Charlton.

Here’s what Glenville’s first town historian, Percy Van Epps, had to say about this marker – which, after all, he selected and wrote. In fact, there were two of these – one at Beukendaal, the other at the point Sacandaga Road leaves Glenville for Charlton.

“As told on the markers, the present road closely follows the course of an old Indian trail leading northward from Schenectady. Indeed, in certain places in lands yet wooded [in 1936], where the road now runs somewhat apart, it is said that the old path, deeply rutted, can yet be traced. At the time of the Battle of the Beukendaal, in 1748 … practically all the area north of that place was yet a dense wilderness, known only to the Indian and a few adventurous white hunters and trappers. Thenpart of the borough or township of Schenectady, the boundaries only of our township had been surveyed, and it was not until some few years after, that certain families of Dutch and Huguenot extraction ventured to chop out and widen this old Sacandaga path, choosing alongside sites for their homes. Prominent, if indeed not first among these were the Conde family and the Van Pattens. Others, however, the Vromans, the Cornells, the Wessels, the Lighthalls, the Groots, the Lows, the Rowley family and many others soon followed …

“Before the close of the century the Sacandaga Road became an important and busy thoroughfare, serving as an outlet for the country to the north. Countless loads of grain and other products from the fertile farms of ‘Scotch Street,’’and from Galway were drawn over this road, to the markets of Schenectady and those of Albany. Lumber, charcoal and tan bark were brought from the hills north of Galway and from the Sacandaga region. And it was along this road that, during the War of 1813, troops and military supplies, even heavy guns, were taken from Albany and Schenectady, up and through the wilderness of the Adirondacks, to Sacketts Harbor. The late Anson B. Hamlin often related seeing in his boyhood days long strings of sleighs loaded with soldiers being taken northward. He said, ‘Looking from my father’s house, the road was black with sleighs.’”

The other two markers at this site commemorate the same event, the Battle of Beukendaal. It was an insignificant little skirmish on the frontier – insignificant unless you were one of the dead or a corpse who had a crow tied to his hand to wave in the reinforcements. The State Education Department marker, which Van Epps says was placed in 1932, says simply:

BEUKENDAAL, 1748

DUTCH WORD MEANING

BEECHDALE. DEGRAFF HOUSE

WHERE 40 SCHENECTADY

MILITIA FOUGHT OFF FRENCH-

INDIAN RAIDING PARTY

That marker was established just three years after the Beukendaal Chapter of the Schenectady Daughters of the American Revolution put up a huge granite monument with a bronze tablet that reads:

1748 IN MEMORY 1929

OF THE MEN WHO WERE KILLED

IN THIS RAVINE IN

THE BEUKENDAAL BATTLE

ON JULY 18, 1748

BY THE CANADIAN INDIANS

JOHN A. BRADT ADRIAN VAN SLYKE

JOHANNES MARINUS JACOB GLEN, JR.

PETER VROOMAN ADAM CONDE

DANIEL VAN ANTWERPEN J.P. VAN ANTWERPEN

CORNELIS VIELE, JR. FRANS VANDERBOGART

NICHOLAAS DeGRAFF CAPTAIN DANIEL TOLL

WHO WERE CITIZENS

ALSO LIEUTENANT JOHN DARLING

AND SEVEN CONNECTICUT SOLDIERS

STATIONED AT SCHENECTADY

1748 was the tail end of what was known as King George’s War, an outbreak of hostilities in North America that meant these residents of Glenville and Schenectady were victims of a battle over succession of the Austrian throne. Below is the story as Van Epps related it, from an account by a survivor of the battle, Albert Van Slyck. We have chosen not to modernize the language, nor to edit much out because this is one of the stories that has resounded with us throughout our life, and it’s worth the telling.

1748 was the tail end of what was known as King George’s War, an outbreak of hostilities in North America that meant these residents of Glenville and Schenectady were victims of a battle over succession of the Austrian throne. Below is the story as Van Epps related it, from an account by a survivor of the battle, Albert Van Slyck. We have chosen not to modernize the language, nor to edit much out because this is one of the stories that has resounded with us throughout our life, and it’s worth the telling.

“On the eighteenth day of July, 1748, a part of men had come together at a farm near the river, a little over a mile west of Schenectady, at a place then called the Maalwyck, to raise the frame of a barn. Three men, Dirk Van Voast, Daniel Toll, and Rykert, a slave of Toll, shortly left the group at the Maalwyck and set out to hunt up their horses, which had strayed off. Not long after this the men at the barn heard firing towards the north, the direction taken by Van Voast and Toll. Alarmed at this a slave was hurriedly sent to Schenectady with a message of warning, which he promptly delivered. At this, doubtless the bell of the Dutch Church sounded a clanging alarm. Not it so happened that there was a company of Connecticut militia under the command of Captain Stoddard stationed in Schenectady at this time. This body of men, under the leadership of Lieutenant John Darling, Captain Stoddard being absent, were at once ordered to go to the Beukendaal, the point from which the sound of the firing was – correctly – judged to come. The company numbered over sixty and was accompanied by five or six young men of the town.

“Van Voast, Toll and the slave, Rykert, in their search for the missing horses, coming near the DeGraff house at the Beukendaal, then unoccupied, heard, as they imagined the sound of horses stamping the ground. This sound came to them from a certain part of the ravine nearby; a cleared spot of bare and salty clay ground known to the Dutch as the ‘kleykuil,’ or clay pit, where deer and other animals came to lick the salty ground. Making their way through the fringe of trees and bushes on the brow of the ravine, expecting to see their horses at the deer-lick, there were startled to see instead, a group of painted savages seemingly engrossed in a game of ‘quoits,’ as Van Voast afterwards described it. This undoubtedly was ‘chunkey,’ a favorite out-door game among many Indian nations; played by rolling a prepared stone, and casting after the moving stone a wooden staff somewhat like a shepherd’s crook.

“Van Voast, Toll and the slave, Rykert, in their search for the missing horses, coming near the DeGraff house at the Beukendaal, then unoccupied, heard, as they imagined the sound of horses stamping the ground. This sound came to them from a certain part of the ravine nearby; a cleared spot of bare and salty clay ground known to the Dutch as the ‘kleykuil,’ or clay pit, where deer and other animals came to lick the salty ground. Making their way through the fringe of trees and bushes on the brow of the ravine, expecting to see their horses at the deer-lick, there were startled to see instead, a group of painted savages seemingly engrossed in a game of ‘quoits,’ as Van Voast afterwards described it. This undoubtedly was ‘chunkey,’ a favorite out-door game among many Indian nations; played by rolling a prepared stone, and casting after the moving stone a wooden staff somewhat like a shepherd’s crook.

“The approach of the men from the Maalwyck was seen at once; if indeed they had not been seen before and the game in progress staged to draw them into an ambush. However this may be, before Van Voast and his companions could turn and get away, Toll was shot dead and Van Voast wounded and made a prisoner. The slave, Rykert meanwhile managed to run clear of the Indian’s [sic] bullets and made the best speed he could toward the Maalwyck.

“Surmising that the escape of the slave would soon result in the appearance of armed men from the Maalwyck or from Schenectady, the wily savages proceeded to lay a trap in the glen. Taking the dead body of Toll, they set it up against a tree, as though alive, and with a short cord they tied a crow they had in captivity, to or directly in front of Toll’s body. Then, compelling Van Voast to go with them, they concealed themselves along the bushy and wooded sides of the ravine, where they awaited the outcome of this unique ruse. Nor did they have long to wait, for Lieutenant Darling and a part of his Connecticut men … soon entered the southern end of the Beukendaal and marched without suspicion and perhaps without caution directly into the ambush set for them with such devilish cunning. As they drew near the curious sight of Toll, apparently alive, sitting with his back to a tree, the crow fluttering before him, the Indians from their concealment opened fire. Eight or ten of the whites were at once stretched dead on the ground and then the yelling savages leaped out of cover with knife and hatchet. At this the greater part of the militia from Connecticut, raw levies, turned and ran, but the men of Schenectady bravely stood their ground, firing their muskets and then using them as clubs, thus the battle quickly became a hand-to-hand struggle. It is said that after the fight the bodies of Glen, DeGraff and other men of Schenectady and Scotia were found lying side by side with the bodies of Indians they had fought with.

“At this critical point in the fight, the little group of Dutch and the few soldiers left, partially sheltered behind trees and stumps, were reinforced by the second party sent out from Schenectady, a small company of New York militiamen headed by Adrian Van Slyck. However, as soon as these men got in line of the Indian’s [sic] fire, like the militia from Connecticut, they also turned and ran.

“It was madness to remain longer; those that had escaped the bullets and the tomahawk of the red man now succeeded in making their way through a western entrance of the ravine to the unoccupied DeGraff house. Here they barred the door and going up to the second, or attic story they quickly pried off clapboards and from the openings thus made poured a deadly fire of bullets at the savages who soon could be seen skulking behind the surrounding trees. While this rifle duel was in progress Dirk Van Voast, wounded and a prisoner, had been left in charge of two young Indians. Eager to see the fight in progress at the house, as best they could they tied Van Voast to a tree and scrambled up the bank of the ravine. Van Voast at once made attempts at reaching his knife, and soon succeeding, cut his bonds and hurried away as fast as his condition would permit. He had not gone very far, however, before he met a third party of armed men from Schenectady, headed by Jacob Glen and Albert Van Slyck. As this last reinforcement came in sight of the DeGraff house the Indians lost no time in taking the old path heading northward through the woods, the present Sacandaga Road, taking with them thirteen or fourteen prisoners. Some of these, by an exchange made two years later, were returned to their homes.”

We’re thankful for the picture from Howard Ohlhous at the Historical Marker Database (oh yeah there is one) because we didn’t have our own photo of these, even though we have driven and ridden past them thousands and thousands of times.

Leave a Reply