For almost our entire life, there was an odd remnant of concrete ramp along the hillside in Schenectady, just where I-890’s ramp to Broadway pitched down the hill. It stood until just a few years ago (at least as late as 2012), but had been blocked off by the highway since the 1960s, and had been out of use well before that. That ramp remnant connected to a once-imposing structure known as the Klondike Ramp. Before the Klondike Ramp, there were Klondike Stairs. Both connected the neighborhood up on the top of the hill, the 11th ward streets of Strong and Summit up on Hamilton Hill, with access into what was once Pleasant Valley Park, enabling residents to get to work at the Schenectady GE and other businesses in the Center Street (Broadway) corridor.

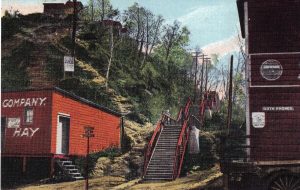

All attempts to understand why these were named “Klondike” seem bound to fail; even legendary Schenectady historian Larry Hart couldn’t offer more than guesses. According to a Times-Union article from 1958, soon after Edison’s works opened in 1886, residents of the elevated neighborhood started walking down the hill to get to work, but found the loose, sandy path a treacherous climb back home, and in 1900 residents petitioned the city to build steps with a hand rail. It took a few years before that actually happened, but around 1905 the stairs were constructed, and the complaining began in earnest. They were ill-kept, the lights were frequently broken by children, garbage was being dumped under the stairs – they were not well-loved. But they did make it much easier to get down the hill. They started at Strong Street, near the intersection with Mumford, angled out down the hill for a bit, and then made a straight path parallel to the hill, basically the same as the highway ramp today.

As early as 1919, efforts to avoid the stairs were made. A roadway was built that year through Pleasant Valley Park, going from Center Street (now Broadway) to Craig Street. “The roadway has been planned to do away with the necessity of the residents on the hill using the steep Klondike stairs while going to and from their work at the General Electric plant.” The road had a pathway alongside it to make it inviting for walkers, some of whom preferred the longer walk to Craig Street over the many steps up the stairs.

In 1929, the same year that Schenectady was moving forward with a new City Hall, the condition of the stairs was such that the city engineer reported that it would be “folly to repair them,” and recommended “a circular ramp and viaduct from the roadway in Pleasant Valley park to Strong street.” How he came up with the circular ramp idea is lost to time – and our interest in this was recently bolstered by a Facebook comment wondering if similar designs had been used elsewhere. Other than in some relatively more modern stadiums, we haven’t found a ramp used to overcome the challenges of getting pedestrians up and down hills, even in cities that have gone to rather famous lengths to do so, such as San Francisco and Pittsburgh. In any event, a circular ramp it was to be.

Interestingly, the engineer’s report identified some problems with that hillside that have continued to this day: it ain’t stable.

“The common council was advised in the report that it was believed inadvisable to rebuild the stairs and walks in their present locations because of the tendency of the side hill slope, along and up which they are built, to slide, due to the nature of the soil and to the superimposed loads of houses and filling along the southerly side of Strong street. The opinion was expressed that unless the dumping and filling is stopped in the rears of the houses and buildings facing the southerly side of Strong street, some of the buildings and fillings will some day be found to have moved part way down the slope, if not to the bottom, because this heavy loading superimposed on top of the slope is quite likely to start a landslide, particularly after the clay soil has been saturated and lubricated by heavy or continued rainfall.”

Turns out, they knew what they were talking about more than 90 years ago. That area continues to slide with periodically devastating results. (There were examples even then – we found one article from 1915 relating how a homeowner was severely injured when his house at Strong and Summit fell down on him as he tried to create a new foundation.)

The solution was in its way rather elegant – rather than a long set of stairs, difficult for anyone with mobility issues, in need of clearing in snow and ice, and exposed to a long hillside that could slide at any point along the way, the new Klondike Ramp would be a standing structure, a circular ramp with seven levels (giving rise to its nickname of “Seven Heavens”), connecting down to street level with the long concrete ramp that stood for so many years. Lots of pitch, but no steps.

The description in the report to the council from the committee on roads and bridges was quite detailed:

“It is proposed to construct the spiral ramp in an eight-sided tower, supported on concrete piers, constructed of structural steel, 64 feet in height about the piers and about 50 feet in outside diameter. The passageway for pedestrians will be seven feet and four inches clear inside width winding and rising upward from the lower landing on a grade of about eight per cent. There are nearly seven complete turns in the tower between the bottom landing, where the ramp from Broadway meets the tower, to the top landing where the viaduct extends to Strong street. The head room between turns on the spiral ramp will be slightly over eight feet. The viaduct extending from the top landing of the spiral ramp will be of steel construction supported on bents which in turn will be supported on concrete piers. The railed passageway of the viaduct will be seven feet and four inches clear inside width. In a bee line the distance between Broadway at the beginning of the ramp and Strong street at the point where the viaduct lands is 530 feet. The difference in elevation between these two points is 110 feet. In order to gain additional distance to overcome this large difference in elevation, the introduction of the circular ramp was decided upon and thus it will be possible to walk from Broadway near the Pleasant Valley park to Strong street near Mumford street on a gradually ascending grade of about eight percent without using any stairs or steps whatsoever.”

Just for the record, eight percent is not a mild grade, although a later document put it at seven percent. Nevertheless, the engineer told the board “that a baby carriage can be wheeled with ease the entire distance.”

In 1930, the contract was let to a DuBois and Son, at a cost of $46,787.70 (somewhat below the bonded amount of $50,000). “Persons using the Klondike ramp will walk about 1,580 feet or about three tenths of a mile . . . It will be much easier to clean the ramp of snow than the old stairs, and the railings along the ramp afford more of a protection against slipping in unfavorable weather than on ordinary walks on the same grade.” It seems like it should have opened in 1931, but we don’t find definitive proof that it wasn’t later.

Curiously, tearing down the old stairs wasn’t part of the project. They were auctioned off as scrap metal (the railings) in 1936, with Buff and Buff offering the winning bid of $10. “The bidder will receive the scrap metal in the abandoned stairs, but will not be required to remove concrete landings which are being left intact to strengthen the steep hill.”

But soon after the ramp was built, its time was already passing. There were trolleys and buses and private cars, with fewer workers walking to the plant. The ramp was a favorite of children who used it for wagon racing, “and people began to fear using the ramp, particularly during the evening when gangs of tough youngsters made the ramp their hangout.” In fact, in 1945, it was noted that six boys were brought to the Chief of Police for throwing rocks and fruit at motorists from the Klondike ramp. He gave them YMCA membership cards and got them involved in the brand new “Pal” league. “They were in need of guidance and discipline, which are afforded by YMCA activities.”

In 1958, the viaduct at the top began to sag, probably the result of moving earth, and the Klondike ramp was quickly closed. At the time, it was not seeing much use anyway. Repair or reconstruction was studied; repairs were estimated as high as $30,000, and reconstruction as much as $110,000, which included precautions to prevent further slides. The City Council voted unanimously to demolish the ramp. The contract went to C.M. Gridley & Son, and demolition was underway in August. During the demo, a worker was hurt in a fall as heavy rains caused the structure to slide and a piece of the structure gave way. It was noted that the contract called for a fence to be installed at Strong Street, which seems like a pretty good idea. But we find no explanation of why the walkway up to the ramp was just left in place. It stood, as we said, until at least 2012, when it’s shown in photos in the Times-Union.

In 1961, the supervisor of the 13th Ward (the wards must have been renumbered or shifted) asked for a stairway from Strong Street to Broadway 50 yards west of the ramp, but soil erosion conditions made it prohibitive. The supervisor, Joel Weiss, wrote “It is hoped that in the future – under brighter conditions – this facility may again be provided.” It was not.

All photographs are from The Grems-Doolittle Library at the Schenectady County Historical Society.

Leave a Reply