The memoirs of Henriette Lucie Dillon, Marquise de la Tour du Pin Gouvernet, touched on one of the most mysterious and unsettling events in Albany history, a mix of fear, fire and racial scapegoating. Her comments on this are enlightening as they certainly reflect the understanding given her by the Albany elites who hosted her at this time, Schuylers and Van Rensselaers, and instructive in the ways they vary from less heated accounts decades later, and of course from what modern minds suspect may actually have happened in the case of the fire of 1793. This is fairly disturbing stuff, and we’re obliged to use the language of the sources.

The memoirs of Henriette Lucie Dillon, Marquise de la Tour du Pin Gouvernet, touched on one of the most mysterious and unsettling events in Albany history, a mix of fear, fire and racial scapegoating. Her comments on this are enlightening as they certainly reflect the understanding given her by the Albany elites who hosted her at this time, Schuylers and Van Rensselaers, and instructive in the ways they vary from less heated accounts decades later, and of course from what modern minds suspect may actually have happened in the case of the fire of 1793. This is fairly disturbing stuff, and we’re obliged to use the language of the sources.

Nearly her first mention of Albany was that the city, “the capital of the state, had been almost entirely burned two years before by an insurrection of negroes. Slavery was not yet entirely abolished in the state of New York, except for children to be born during the year of 1794, and only when these had reached their twentieth year … One of these ‘blacks,’ a very worthless character, who had hoped that the act of the legislature would give him his liberty without conditions, resolved to be revenged. He enrolled several miserable fellows like himself, and on a fixed day arranged to set fire to the city, which at this time was constructed mainly of wood. This atrocious plan succeeded beyond their expectations. Fires were started in twenty places at once, and houses and stores, with their contents, were destroyed, notwithstanding the efforts of the inhabitants, at the head of whom labored the old General Schuyler, and all his family. A little negress, twelve years old, was arrested at the moment she was setting fire to a store with straw from the stable of her master. She revealed the names of her accomplices. The next day a court assembled upon the still smoking ruins, and condemned the black chief and six of his accomplices to be hung, which sentence was executed at once.”

We can perhaps forgive the Marquise for an imperfect memory, as she was writing these memoirs no sooner than 1820, and perhaps much later than that. And recall that she had lived through the Reign of Terror. So she may well not have remembered all the particulars … but what she did remember is telling: a conspiracy of slaves, mass arson, and Schuyler heroism. Coming to Albany as a guest of the Schuylers, who did her some very substantial favors, she would of course be inclined to believe and relate a Schuyler-centric view of events.

Writing in 1867, Albany’s chronicler Joel Munsell presented a somewhat different view of events from 70 years before, using an undated article from the Albany Evening Journal:

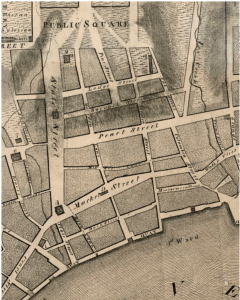

“Sunday, the 17th of November, 1793, was a day long remembered by the inhabitants of this city, and the few who still linger among us retain a vivid recollection of the scenes enacted during that night. The greater portion of the then quiet church-going people of that day had retired to rest, and were slumbering upon their pillows, when they were awakened by the alarming cry of fire … The fire originated in a barn or stable, belonging to Leonard Gansevoort, in the centre of the block then bounded by Market, State, Maiden and Middle lanes, in the rear of the store on State street now occupied by Hickcox and Co.”

It started in that stable, but quickly spread and destroyed that block.

“The fire laid waste all that portion of the city previously described, from the dwelling house and store of Daniel Hale, northerly to the dwelling house of Teunis T. Van Vechten, on the corner of Maiden lane and Market street (now Broadway), destroying on that street the dwelling houses and stores of D. Waters, John G. Van Schaick, E. Willet, John Maley, James Caldwell, Caldwell & Pearson, C. Glen, P.W. Douw, Maley & Cuyler, and Mrs. Beekman. On State street, there was consumed the dwelling house of T. Barry (then a new and considered an elegant brick building), the store house of G.W. Van Schaick; the house of C.K. Vanderberg, partly occupied by Giles K. Porter, merchant tailor; the dwelling of Leonard Gansevoort; the drug store of Dexter & Pomeroy, and the dwelling of Mrs. Hilton. In Middle lane, there were a large number of stables, all of which were consumed, greatly aiding in the spreading of the fire by the intense heat made by the burning of pitch-pine timber, which was used for building in those days. In Maiden lane the dwelling house of Mrs. Deforest and the new and spacious store house of Maley & Cuyler were destroyed, the latter firm being by far the heaviest losers by this calamity.”

The bucket brigade was called out (at that time, every house was required to have three leather water buckets), and two primitive fire engines were put to use. Wet blankets were put up on roofs, and at least one building was chopped down in order to check the progress of the flames. Cold rain followed by sleet probably did the most to put it out. Then began the scapegoating, and one of the most shameful episodes in Albany’s history.

“The fire was so plainly the work of an incendiary, that not only were several slaves arrested upon suspicion, but subsequently a meeting of the common council was held and an ordinance passed forbidding any negro or mulatto, of any sex, age or description whatever, from walking in the streets or lanes after 9 o’clock in the evening, or from being in any tavern or tippling house after that hour, under penalty of twenty-four hours confinement in the jail.”

After being jailed for 24 hours, then they could seek to prove that they were upon lawful and necessary business, if supported by their master or mistress (ignoring that there were free blacks). If they established that, they had to pay the jail expenses (!); if they failed, there was further fine and imprisonment.

As Munsell tells it, “tradition asserts” that a young man named Sanders, of Schenectady, had been seeking the attentions of Leonard Gansevoort’s daughter, but was rejected by her or her father. Apparently this was a high insult, and Sanders in some way enlisted a friend named McBurney who was a jeweler in State street in Albany. McBurney, in turn, called on a slave named Pomp (or Pompey), who served Matthew Visscher, and promised a gold watch for anyone who would set fire to Gansevoort’s stable on a certain night. Pomp, it was written, either lacked the “moral courage to commit the act,” or preferred not to have it associated with him and so he enlisted two female slaves. One was Bet, 16 or 17 years old, who served Philip S. Van Rensselaer; the other was Dinah (often given as Dean), about the same age, served Volkert Douw.

“After Pomp had concluded the negotiations with the girls, to commit the arson, he apparently became alarmed, and fearing the consequences that might ensue, endeavored to prevail upon them to relinquish the thought of committing the fiendish act. The same evening, Pomp was seen in his master’s stable, in company with the girls, endeavoring to persuade them from doing it, and a short time previous to the breaking out of the fire he was seen with them in Middle alley, talking to them in a supplicating tone of voice. In fact he was overhead to say, that he would not give them the watch if they committed the deed.”

Boy, does that not add up. Munsell’s account gets a little confusing, saying that Bet carried live coals from the kitchen of Mr. Gansevoort to his barn in an old shoe, and threw them upon the hay. It didn’t take as quickly as she expected, so she brought more coals, and this time “the conflagration speedily ensued.” Then Munsell seems to say there were two different fires, which doesn’t match up with any other accounts we found. He says that the next day “after the fire of the 17th these same girls set on fire the stable of Peter Gansevoort in the rear of his house, on the corner of Market street (now Broadway) and Maiden lane, which was also destroyed, and the same evening visited the house on the opposite corner, and attempted to set it on fire by putting coals of fire in a bureau drawer containing clothes. It did not succeed for want of air.” Whether this somehow came from one of the girls’ confessions, or from Pomp’s stories, it is not clear, but all other accounts say the fire was on the 17th, making this part of the tale inconsistent.

Other (later) accounts say that Bet and Dinah took live coals from Douw’s house, and went with Pomp to the Gansevoort stable, where Pomp put the coals into a pile of hay. From a distance, this seems more reasonable.

Shortly after the fire, Bet and Dinah were arrested. They admitted guilt and implicated Pomp, who was also then arrested. There was a rush to judgment, and from judgment to execution. At trial in January 1794, the girls pled guilty; Pomp professed his innocence. “The girls were executed in the following spring [March 14] on Pinkster hill, which was then a few rods west of the Academy, or about on the corner of Fayette and Hawk streets. The revelations [a later confession] made by Pomp were given to Gov. Clinton, and a few months after the execution of the wenches, Pomp suffered the extreme penalty of the law upon the same spot [April 11]. Sanders and McBurney were not arrested, for there was no evidence against them except the assertions of Pomp, and he being implicated in the crime his evidence could not be taken.”

The fire and resulting executions have been the subjects of modern articles and even dramatic vignettes. The idea that Bet and Dinah (also given as Dean) would have insisted on going through with the act, over the protests of Pomp, is clearly nonsense, probably taken from one of Pomp’s declarations of innocence. None of the three had any known grievance against Gansevoort.

So from this, as a number of other writers have noted, were passed the aforementioned restrictions on the movements of African-Americans. This has sometimes been grouped with slave rebellions, although it was clearly nothing of the sort. In fact, a brief entry in the Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Volume 1, charges that Pompey was hired to set the fire by “five white men who had a grudge against the landowner . . . An explanation of the grudge is suggested by contemporary accounts that show Thomas Bissbrown, watchmaker, had recently moved his shop from a prominent location, rented from Leonard Gansevoort, to a less advantageous one. A rival watchmaker, newly arrived in Albany, was in Bissbrown’s former location.” (This version of events seems to come from a 1977 article in the Journal of Black Studies, “Black Arson in Albany, New York, November 1793.”) But Munsell’s account gives no mention of this watchmakers’ rivalry.

And somehow, many years later, the Marquise had converted these events into something really quite different, almost entirely removed from the facts. An act of hired revenge was turned into a plot to burn the city as a redress for slavery, with fires started in 20 places at once. The actions of three teenage slaves became those of a large mob, and Bet became even younger than she really was. A trial and later execution, stayed at least once by the governor, became summary judgment and instant execution. What was, of course, a terrifying event for all concerned became something not driven by either a jilted (white) lover or an angered (white) businessman, but instead by angry slaves, who served as convenient scapegoats.

Leave a Reply