If in, say, the 1780s anyone were taking bets on which local community might someday rise to rival Albany’s mercantile power, they would likely have favored Lansingburgh as the capital city’s chief competition. Schenectady was a sleepy community of broommakers and hops growers, though still a gateway to the west for the few who went that way (the terrors of the Revolution had proven a serious dissuasion to continued settlement farther west, and it took some time to recover). Other communities around the region, all huddled on the banks of one river or the other, were even less than that. The only other real seat of prosperity lay several miles up the Hudson in Lansingburgh, often called “New City,” which in 1787 had 500 inhabitants to the Old City’s (Albany’s) 3000. That was before things started expanding down at the Van der Heyden farms.

If in, say, the 1780s anyone were taking bets on which local community might someday rise to rival Albany’s mercantile power, they would likely have favored Lansingburgh as the capital city’s chief competition. Schenectady was a sleepy community of broommakers and hops growers, though still a gateway to the west for the few who went that way (the terrors of the Revolution had proven a serious dissuasion to continued settlement farther west, and it took some time to recover). Other communities around the region, all huddled on the banks of one river or the other, were even less than that. The only other real seat of prosperity lay several miles up the Hudson in Lansingburgh, often called “New City,” which in 1787 had 500 inhabitants to the Old City’s (Albany’s) 3000. That was before things started expanding down at the Van der Heyden farms.

There were three of them. The northern most was between Division Street and the Piscawen Kill, near current Hoosick Street, not very visible from the River Road; its one-story dwelling, built in 1756 by Jacob I. Van der Heyden, stood on a rise of ground not far north of the Hoosick Road.

The middle farm lay between Grand and Division streets, and had a two-story board building on the east side of the River Road, opposite a ferry “which for many years had been a source of income to the family. Jacob D. Van der Heyden, then enjoying the privilege of ferrying vehicles, animals and people to and from Steene Hoeck, resided in the old house….” Steene Hoeck was a site on the west bank (later West Troy, now Watervliet) known as Rock House. Just a bit further south was the third farm, a one-story brick dwelling built in 1752 by Mattys Van der Heyden. It sat about 1300 feet north of the Poesten Kill.

According to Arthur James Weise, in his “Troy’s One Hundred Years, 1789-1889,” after the Revolutionary War, migrating New Englanders heading to Lansingburgh and beyond saw how well situated the Van der Heyden places were, particularly with regard to navigation, and pleaded to be able to lease plots of land. Few were successful. Benjamin Thurber of Providence was allowed to rent, not lease, land from Jacob in 1786 for a dwelling and a store on River Street, just south of Hoosick Street. He grew quickly, serving neighborhood farmers. Around the same time, Captain Stephen Ashley of Salisbury, Connecticut, sought to settle near the ferry, but was denied. Taking the same request to Matthias, grandson of the builder of the southern farm, Ashley found a less prosperous landowner more inclined to listen. Captain Ashley got a two year lease on the brick house, fitted it for a public house, and called it the Farmers’ Inn. Then he established a new ferry, which soon came to be known as Ashley’s Ferry. What Jacob thought of this ferrying competition, Weise does not record.

Ashley and a gentleman from Providence named Benjamin Covell realized that Jacob’s middle farm enjoyed a deeper river channel and a steeper, firmer shoreline, and started pressing Jacob to have the western part of his land laid out for the site of a village.

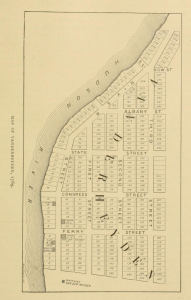

“After considerable reflection, he finally engaged Flores Bancker of Lansingburgh to lay out about sixty-five acres into lots, streets, and alleys. When the map of the plat was completed on May 1st, 1787, the Dutch farmer, in honor of his family, called the site of the projected village, Vanderheyden. As related by an early settler, the place was, ‘with a foresight not always observed, laid out with a view of its ultimately being a place of considerable magnitude; and Philadelphia, with its regular squares and rectangular streets, was selected as its model by the advice of a gentleman, who had made a then rare visit to that celebrated city.’

As seen on the map of Vanderheyden, the village comprised two hundred and eighty-nine lots, mostly fifty feet wide and one hundred and thirty deep, with alleys in the rear of them twenty feet wide; the streets having a width of sixty feet.”

So, important to note: one of the great things about Troy, its alleys, goes back to its very beginning.

Ashley built a new two-story wooden inn at the northeast corner of River and Ferry streets. The southern ferry business having been established. Matthias Van der Heyden put a notice in the May 10, 1788 Lansingburgh Federal Herald.

“The subscriber respectfully informs the public that as the time for which he leased his ferry to Captain S. Ashley hath expired, he proposes to exert himself in expediting the crossing of those who may please to take passage in his boat, which will ever be in readiness directly opposite the house at present occupied by said Ashley. The terms of crossing will be as moderate as can reasonably be expected, and a considerable allowance made to those who contract for the season. He has in contemplation to commence keeping a tavern in a few weeks from the date hereof, when no exertions of his shall be wanting to accommodate those who shall resort the house from which Mr. Ashley will shortly remove.

N.B. Notice for crossing will be given by sounding a conk-shell a few minutes before the boat starts.”

The new town of Vanderheyden was quickly a success. One store after another opened. Asa Crossen, a “taylor and habit-maker” from New London, Connecticut, advertised that he was carrying his business “in all its branches at Messrs. Ashley and Van der Heyden’s ferry.”

Many of these new residents were from somewhere else, particularly New England, and maybe that led to what happened next. Not even two years after Jacob Van der Heyden had agreed to split up his land into a village, the new residents started pressing for a name change.

“Considering the name Vanderheyden too polysyllabic, Dutch, and strange, the settlers determined to select a shorter and more acceptable designation for the village. On Monday evening, January 5th, 1789, they met at Ashley’s Inn, near the north-east corner of River and Ferry streets, and voted that the action taken by them in the choice of a name should be published in the Albany and Lansingburgh newspapers . . . The summary repudiation of the original name by the settlers was harshly criticised by the members of the Van der Heyden family. Jacob D. Van der Heyden was sorely offended, and for a number of years thereafter continued using the former designation in his conveyances, by writing it, ‘Vanderheyden alias Troy.’”

A week after the renaming, a pseudonymous critic going by the name of “Nestor” published a paragraph in the Lansingburgh paper:

“Yesterday I hear’d that a neighboring village had assumed the name of Troy – for what reason I cannot conceive, as I find not the least resemblance between the old city of that name and this small village. – Some classical critic has perhaps thought fit so to style it, from dissimilitude, as lucus is derived a non lucendo. – Some wag must surely have been playing a trick with the good people of the place, and is now laughing in his sleeve at their ignorance of ancient history. Let them consider what constructions may be put upon their choice, when it is so public known how the letters of said title may be placed, and what they signify. First, Tyro, in Latin, is a novice, a fresh-water sailor, or a fair-weather soldier. Second, Ryot, (according to the old way of spelling,) and surely they are not so famous for kicking up a dust that the letters composing the name of their town designate their character. Lastly, Tory; this alone would be sufficient to induce them to reject what ever bears the least resemblance to so hated a character.”

Unfavorable anagrams notwithstanding, the name stuck, and the village of Troy continued to grow.

Leave a Reply