Ripley’s “Romance of a Great Factory” from 1919 gives us an unsurprisingly romantic view of the Schenectady General Electric works at that time. In addition to providing us with Charles Steinmetz’s private shorthand method, its appendix section (titled “Fragments”) gave a little recitation of industrial accident facts to show that life at GE was pretty safe, especially in comparison to some occupations.

“A man who fishes for a living is really in a very dangerous occupation, as on the average three men out of 1,000 lose their lives at this work every year. Comparing this with the figures of the General Electric fatalities . . . it is seen that in round numbers that it is 30 times more dangerous to fish for a living than to work in the General Electric shops, surrounded by high pressure steam, high voltage electricity, with tons of steel and cast iron being swung over your head by the electric cranes, and with tens of thousands of tons of freight moved daily on the two railway systems within the works.”

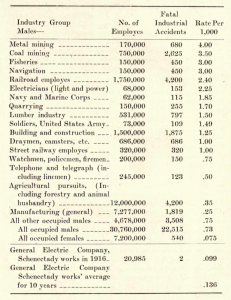

Using figures from 1913, Ripley showed that pretty much every industry of the time had a significantly higher rate of fatal accidents than the GE Schenectady works did. At a time when the works employed nearly 21,000 people, it suffered only two fatalities in 1916 (a rate of 0.099 per 1000). Only the line of “general” manufacturing even approached GE’s rate, at 0.25 per thousand. Only the overall rate for “all other occupied females” fared better than GE, at 0.075 per thousand.

Using figures from 1913, Ripley showed that pretty much every industry of the time had a significantly higher rate of fatal accidents than the GE Schenectady works did. At a time when the works employed nearly 21,000 people, it suffered only two fatalities in 1916 (a rate of 0.099 per 1000). Only the line of “general” manufacturing even approached GE’s rate, at 0.25 per thousand. Only the overall rate for “all other occupied females” fared better than GE, at 0.075 per thousand.

“Who would ever imagine that men engaged in agricultural pursuits, the farmers, should suffer from a high rate of ‘industrial accident?’” Hoxsie has met a lot of farmers and even today, their fingers often don’t add up to 10, so this is no surprise.

It’s a little hard to make a comparison to the present day, as what is included in these categories may have changed over time. What then fell under draymen and teamsters would almost certainly be truck drivers and freight loaders today, with a whole different set of threats. It’s certainly safer today to be a street railway employee, though the opportunities have also decreased. But for even a rough comparison, the building and construction trade saw 1875 deaths in 1913. In 2014, the private construction industry saw an uptick in fatalities, to a total of 899 (according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics). If you lump together mining and quarrying in 1913, there were 3560 fatalities. A century and a year later, fatal injuries in the private mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction industries rose to 183. BLS now lumps farming, fishing and forestry together, with 253 deaths (77 of those in logging) in 2014; in 1913, that number was probably more like 5,447.

Since those are absolute numbers, not rates, it helps to have a little bit of perspective. In 1913, the US population was about 97.23 million. In 2014, it was about 318.9 million – 3.28 times greater.

So for everyone who says, “We didn’t used to have all this safety stuff, and we were fine” – no, you weren’t. You died in droves. Unless, of course, you worked at the Schenectady works.

Leave a Reply