The Wright Brothers first achieved sustained, powered, heavier-than-air flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in December 1903. Their first flight was 120 feet for 12 seconds; their fourth and final flight of that day covered 850 feet in 59 seconds. However famous that is now, the flight was barely noticed at the time. Their suspicious and sometimes contentious relationship with the press meant that much of what they did in subsequent years was little reported, or received with skepticism. Even when the press was allowed to watch, photography was banned, leading to more questions than answers.

So it was that the first public flight of a heavier-than-air craft really wasn’t until 1908, when F.W.”Casey” Baldwin took off from the frozen surface of New York’s Keuka Lake and covered 318 feet, 11 inches for 20 seconds before crashing into the ice. Baldwin was part of a group called the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), which included Alexander Graham Bell, J.A.D. McCurdy, Army Lieut. Thomas Selfridge, and a young man from Hammondsport in the Finger Lakes named Glenn Hammond Curtiss.

Curtiss was a bicycle racer who built his own bicycles, then branched into motorcycles and other motorized vehicles and craft. He developed the motor that powered America’s first dirigible. His V-8 powered Hercules motorcycle achieved 136.3 mph in 1907, gaining Curtiss the title of “Fastest Man on Earth.” Two months after Baldwin’s flight, Curtiss flew an AEA plane 1017 feet in controlled flight, using horizontal rudders (ailerons) on the wings. In 1908, he competed for a Scientific American trophy that required flying in a straight line for one kilometer. In what is characterized as the first officially recognized, pre-announced and public observed flight in America, Glenn Curtiss flew 5090 feet. A year later, he flew 24.7 miles, and in another race set a speed record of an average 46 mph.

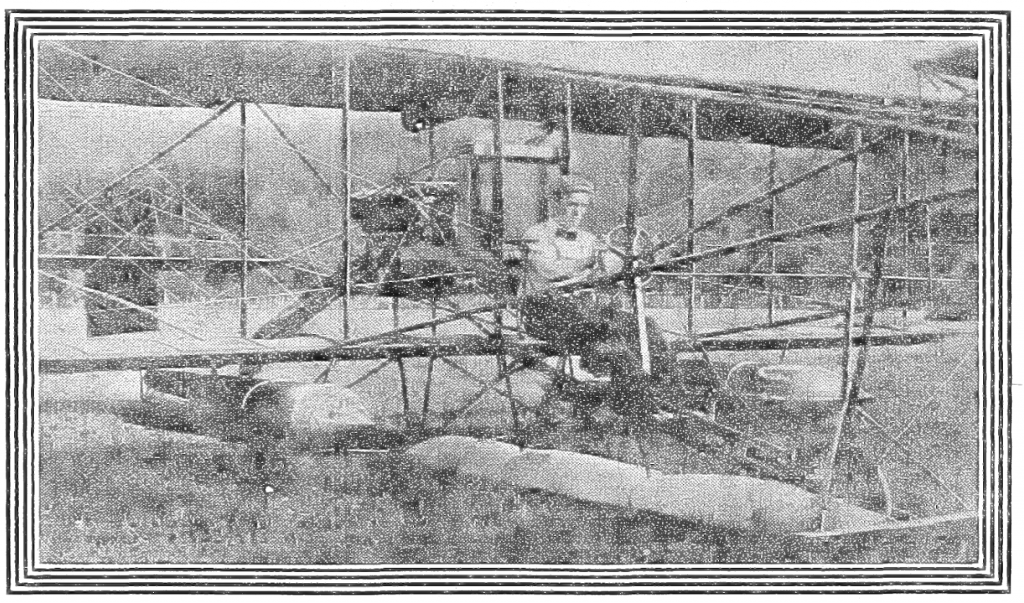

Hammondsport is a long way from Albany, so why are we talking about this? Well, in 1910, the New York World newspaper (publisher: Joseph Pulitzer) offered a $10,000 prize for the first successful flight between Albany and New York City following the Hudson River route. Two stops would be allowed, because it would be impossible for an airplane to carry that much fuel. Glenn Curtiss was determined to win the prize. It’s a little amazing to think that in the course of just a few years we went from powered flight that hardly anyone knew about to being able to fly a kilometer in a straight line, to, just two years later, flying from Albany to NYC. It was touted as the longest route devised over water. It was certainly not the same as flying over open ocean or a Great Lake, but flying down the Hudson presented some pretty formidable challenges for a craft of the time. For starters, we’re still talking about an open biplane — two fabric wings, rear-mounted wooden propeller, no cockpit. Basically, a powered kite. To facilitate a potential water landing, his airplane was fitted out with two tin floats.

In late May of 1910, Curtiss came to Albany to prepare for the flight. The New York Times reported that

“The aviator has been making much quiet preparation for his feat. For the last six months, off and on, he has been experimenting to determine the ability of his latest model to alight on the water and to keep afloat there without upsetting. Other aviators have alighted on water before now, but none has done it intentionally, and their accidents have revealed next to nothing that could be of benefit to Mr. Curtiss. The latter, however, has fashioned a sort of apron arrangement which he expects will keep his craft right side up should it drop with him into the Hudson, and by means of which he hopes, in the event of a fall, to be able to rise again.”

The weight of his safety devices, “which will include life buoys,” meant he couldn’t make the trip without stopping for fuel, and the plan was to do so just south of Poughkeepsie.

“His biplane will weigh 1,000 pounds, inclusive of his own weight of 145 pounds. It will be equipped with an eight-cylinder motor, developing 50 horse power. According to the aviator, it has a spread of supporting surface less than one-half that of any other biplane now in use.

The start will be made from [Van] Rensselaer Island, below the bridges across the Hudson at Albany, about 4 o’clock to-morrow morning [May 26] if the weather conditions prove favorable. If not, the start may be deferred until nightfall. Should he start in the morning Curtiss expects to reach here some time in the afternoon. A night start will necessitate a stop all night at Poughkeepsie, and the resumption of the flight on Friday morning.

The problem of alighting in this city has bothered the aviator, but he expects to be able to land at the Battery. The high buildings, occasioning conflicting air currents, he expects to prove his greatest source of trouble.”

Curtiss had taken the steamship Albany along the river to reconnoiter the proposed route of his flight, and tried to study the air currents over the river. He expected to take off on the 26th, but missed that window.

“Through twelve hours of constant work upon his aeroplane to get it in shape for its proposed flight down the Hudson to New York, Glenn H. Curtiss, the aviator, convinced a large gallery of Albany residents to-day that aerial navigation, so far as getting readily aloft is concerned, is still far from a perfect science. By his delay Curtiss lost a favorable day for a flight.

Mr. Curtiss’s five mechanics swarmed upon his machine early this morning and eased work only when the darkness made it impossible to continue. The aviator, who had directed the task at intervals, said as he left his craft for the night that there was still eight hours’ work ahead of him before it would ready to test in a preliminary flight. . . .

For twenty minutes just at sunset Curtiss brought his machine out of the two-pole tent where it has been assembled on the tide flats of Van Rensselaer Island, just outside the Albany city limits. It was then ready for flying except that harmonies have still to be established between the front and rear rudders, and that the ‘Ailerons,’ as the small movable planes between the main planes are called, had not yet been put in place.

Curtiss started his engine several times for the delectation of the multitude which assembled in automobiles, in carriages, and on foot. As the big wooden propeller blade picked up its thousand revolutions a minute it forced a spurt of air out behind it which turned straw hats into gliders by the score and sent them spinning toward the Hudson.”

The craft was compared to the “June Bug,” a machine that Curtiss had taken to Governors Island during the previous year’s Hudson-Fulton celebration but in which he had done little flying, disappointing the crowds who had come to expect something spectacular. The new craft, known as the “Albany Flyer,” was eight feet longer in wingspan. Black balloon cloth was used in place of silk and brown varnish for the wings. The front elevating planes were larger, as were the ailerons and the rear rudder.

His plan was to not only follow the river’s route, but to stay close to its surface. “I shall fly close to the water all the way down, and if I’m upset I shall count on my five airbags and two tin airtight compartments to keep afloat. My hydroplane attachment in front will force the machine to skim along on the surface until by the loss of speed and momentum it gradually settles to a depth of about two feet, just the tips of the lower plane and half the propeller blade projecting above the surface. All I will have to do will be to stand upon the seat to keep my feet dry and wait for help. If I am compelled to do that this trip it will probably cause me to lose the event, as I cannot start again from the water, and I have little faith in being able to tow the craft ashore in condition to take the air at once from land.”

By the way, the Times wasn’t kidding around in its coverage. It had engaged a special New York Central train with “a fast locomotive and a single coach car, prepared to leave at a moment’s notice to accompany the aeroplane on its journey.” The train would have priority over all other trains, and would carry Times reporters and Curtiss’s wife. Curtiss said he could keep the train company “so long as it went no slower than forty-five miles an hour.” From the train “a bulletin service to The Times on the progress of the flight will be maintained.” Curtiss expected to reach Poughkeepsie in an hour and three quarters; three miles south of that city, he was to take on twelve gallons of gasoline and replenish his oil and water supply at the Gill farm. That stop was to take about fifteen minutes, and then he expected to reach New York in two more hours. “His present intention is to land at Battery Park, or if the cross wind currents from the skyscraper district are too strong to permit him or effect a safe landing there, then at Governors Island.”

Leave a Reply