The Albany and Hudson Railway, which provided trolley service from Hudson to Rensselaer and into Albany, only lasted under that name from 1899 to 1903. In addition to running the trolleys, the company ran a resort called “Electric Park” at Kinderhook Lake. A round-trip ticket from Albany to Electric Park cost forty cents. Extra cars ran on Sundays and holidays to serve the park.

The Albany and Hudson Railway, which provided trolley service from Hudson to Rensselaer and into Albany, only lasted under that name from 1899 to 1903. In addition to running the trolleys, the company ran a resort called “Electric Park” at Kinderhook Lake. A round-trip ticket from Albany to Electric Park cost forty cents. Extra cars ran on Sundays and holidays to serve the park.

On a late spring Sunday, May 26, 1901, trains were running to and from the park, filled with those who wanted to enjoy the park’s two Ferris wheels, carousel, vaudeville amusements and boating. (The roller coaster wouldn’t be built until 1907.) Train 22 left Rensselaer at 3:17 pm, two minutes late and carrying, after some stops, 83 passengers. Frank Smith of North Chatham was the motorman, and Charles Johnson of Clinton Heights the conductor. Train 19 set out northbound from Kinderhook Lake 3 minutes later, running 20 minutes behind with about 20 passengers. William Nicholas of Rensselaer was the motorman, and Seward Clapper of Nassau the conductor.

Much of the line was single-track, necessitating careful timing and the use of sidings so that cars could pass each other. At a spot known as siding 69, somewhere on the border between East Greenbush and East Schodack, there was a deep bank to the west and a large bluff to the east, creating a bend with no visibility along the tracks. Northbound No. 19 got to siding 69 at 3:30, “on the south side of the bluff and slowing up to give [conductor] Clapper a chance to drop off and turn the switch in the siting just ahead, when, without a moment’s warning the south-bound car [No. 22] dashed around the corner at full speed, and before the motorman could even shut off the power or put on the brakes, the cars collided, knocking each other almost to pieces in the jam of telescoping.”

The Times-Union’s coverage the next day was nothing short of sensationalistic:

“In the cars were two masses of injured humanity huddled together in conscious and unconscious state. Beneath them trickled their own blood, and in answer to their appeals for help came back, the moans of injured men, the screams of hurt women and the voices of children. For the minute those who had life left in them were too stunned to realize what had happened. Shock and pain gave them patience, as it were. Then began the race of life. Those of the passengers who were not so severely hurt as to be unable to assist began the work of rescue. The task was slow and wearisome. One by one the dead and the injured were extricated from the wreck and sent to places where they could be best cared for under the circumstances until the arrival of the surgeons.

Dr. W.F. Allen, of Rensselaer, was the first to reach the scene. He was followed by Drs. Powell and Griswold, and O’Hare of Nassau; Kern and French, of East Albany, and Garrison and Humphrey, of Rensselaer. The rural district was turned in a moment from quietude to an immense operating room. Where but a few minutes before the blades of grass stood erect and green, the forms of men, women and children were stretched in all their bloody repulsiveness … The saddest carload that ever entered Rensselaer was that which arrived shortly after 6, earing the mangled bodies of Motormen Smith and Nicholas, with the floor of its baggage apartment and every seat filled with wounded, some unconscious and many groaning with pain.”

Four were killed immediately, motormen Smith and Nichols, Miss Annie Mooney of Stuyvesant and Miss Maud Kellogg of Ballston. The next day another passenger died, Daniel Mahoney, a mate on the steamer Dean Richmond. Those who survived suffered every kind of laceration, broken bone, bruise, concussion and other injury imaginable.

Conductor Clapper said he was standing by Nicholas. “the car was slowing down and I was just ready to jump out and run ahead to throw the switch when I heard Nicholas cry, ‘Good god, there she comes, jump, jump!’ I looked and saw No. 22 coming like the wind and right on us. It seemed as though I had no more than thrown the door wide open and jumped before the crash came.” Nicholas wasn’t so lucky. The Times-Union didn’t spare its readers the grisly details of the conditions of the motormen’s bodies.

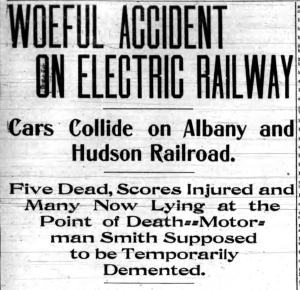

Even in its first reporting, the Times-Union speculated that motorman Frank Smith was to blame. Under the headline “Was Smith Temporarily Demented?” they reported stories that he was either demented or mentally incapacitated “at the time he took the car from the switch at the high rate of speed at which it was going, when he new that another car was in all probability dashing towards that point in an endeavor to make up time lost. It is said that ever since the sad death of his wife some time ago he has been depressed, and at times was very remorseful and sullen. Possibly one of such mental spells was upon him and caused him to forget the danger which threatened him when he disregarded the rules of the company.” An official investigation also placed the blame on Smith “not stopping at siding No. 69, where he should have met car No. 38 on run No. 19.” But his conductor was also assigned some of the blame, as he “should have been on the lookout to see whether car No. 38 of run No. 19, was on the siding or not.” His mental state was not described. The rules of the railroad were not found to be at fault.

As terrible as the accident was, it wasn’t the last fatality on the line. The very next summer, August 4, 1902, a trolley headed from Electric Park to Hudson came to a stop, possibly from losing contact with the third rail. The next car behind it, an extra car to handle the summer crowd, came quickly behind at about 40 mph and slammed into the back of the stalled car. Again, the injuries were horrendous, with two dead at the scene and another dying of her injuries some days later.

Leave a Reply