Yesterday, in talking about plans to replace the old Greenbush Bridge, we noted the somewhat odd comments of Holland Tunnel designer Fred Williams, who had come to Albany to talk about how you should always think about a tunnel, but lamented that “This isn’t tunnel day.” Well, that wasn’t as random as it sounded – turns out, a tunnel had been seriously considered earlier that same year.

Yep. On Feb. 14, 1928, the Albany Evening News unveiled the first description of a proposed tunnel under the Hudson River between Albany and Rensselaer, proudly announcing “Albany – Rensselaer Project Will Introduce Maj. Hewes’ Spiral Staircase Approach – Nassau Architect to Show Drawings Thursday at Public Discussion of Plan in City Hall.”

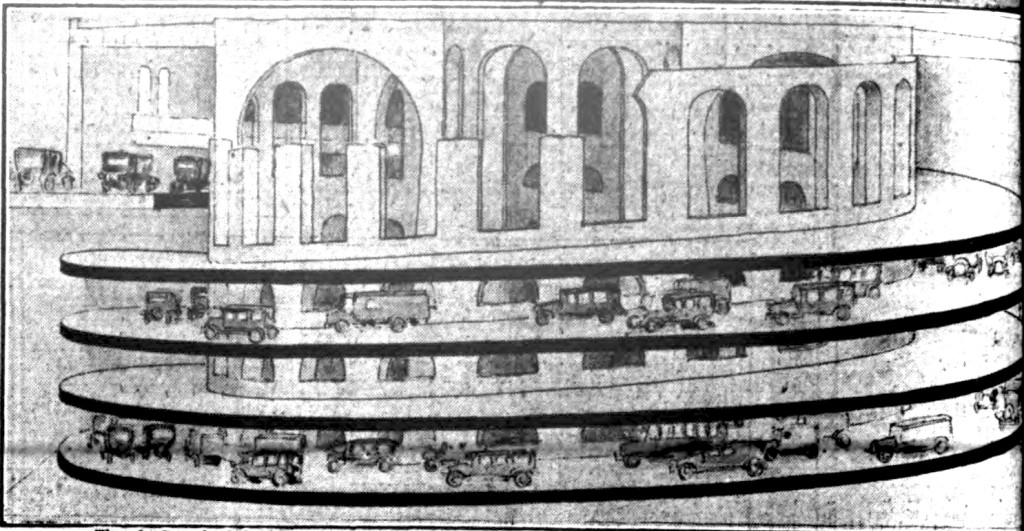

The project provides for circular approaches, an engineering concept that may have profound effect on future tunnel construction. Traffic goes into and out of the tunnel by means of a spiral “staircase,” an expedient heretofore unthought of and which resulted from special study of landscape conditions prevailing here and in Rensselaer.

The idea originated with Major James E. Hewes, an engineer and former executive of the Eastern New York Utilities company. He is a member of the Albany-Rensselaer bridge committee, created to determine whether a new structure is needed between the two cities and what form that project should take.

There would be a public discussion of the plan at City Hall, with Nassau architect Herman Kobbe, who was associated with Hewes, to display “a series of water color and pen and ink pictures of the project.” It was confidently expressed that the total project, including land, dredging, the tunnel and ventilating systems would not exceed $5 million.

Location–The Albany terminal would be a few hundred feet north of the Greenbush bridge and would be situated in Riverside park extending from the river to Broadway. In Rensselaer the terminal would be directly in front of the Huyck mills with exit and entrances to Broadway.

These proposed terminals would serve not only to shelter the ramp approaches dipping into the earth but could be utilized for office, manufacturing or state and municipal requirements, according to Major Hewes. Because of the substantial foundations necessary for the ramps, a building of almost any height could be erected over them. The buildings would have an area of 300×300 feet each, providing 90,000 square feet of space to the floor. Major Hewes believes that each building could be made to provide an annual rental return of $200,000.

The Approaches–Entrance and exit of the terminal would be at street level. In order to forestall the danger of high water, with terminals built at the river brink, the street at that point would be elevated a few feet. This would make the top of the ramp at least four feet above the height of the highest water ever recorded here.

The ramps would be thirty-four feet wide of reinforced concrete construction. Two types of ramp construction are named. One provides for a ramp within a ramp. This would permit unobstructed passage for traffic descending to the tunnel, while traffic bound upward would travel the second ramp.

The other type of ramp provides for two distinct approaches, side by side. One for ascending, and the other for descending traffic.

Listen, we’re living in the 21st century. Ramps aren’t entirely a rarity. But in 1928? Not terribly common. They needed explanation.

An automobile entering the Albany terminal at street level would begin the descent to the tube at once. On the downward trip the motorist would make two complete circles before reaching the tunnel level. He would descend a total of 76.8 feet and would actually travel 1,920 feet over a four per cent grade, a trifle less sharp than the grade of the State street hill between James street and Pearl street.

The Tunnel–The tube itself would be 860 feet long. It might contain two roadways, one superimposed above the other with a four foot fill between. The idea here would be to divide east and west bound traffic, or to make both levels two way, and limit trucks and heavy vehicles to one level only. Another plan would provide but one roadway, resting on the bottom of the tunnel.

The article noted that the tunnel would be flat, not sloping like the recently completed Holland Tunnel; the tube would be 50 feet in diameter, steel reinforced concrete built near the site and then lowered into the river onto a dredged bed and joined, then covered so that it would have four feet of stone above it as protection against a boat sinking and coming to rest on top of the tube. Major Hewes was confident the whole thing could be put in place in less than two years, and that at no time would the work interfere with navigation. Maybe so. We never found out.

Leave a Reply