Yesterday we read the exhortations of Samuel Ruggles, champion of improvement, for the establishment of a National University at Albany. So, what happened with that?

The dream of a national university was as old as the dream of our nation itself.

The idea was first attributed to Samuel Blodget (sometimes Blodgett), who was said to have, in General Washington’s presence in 1775, suggested that the damage done by the militia to the colleges in which they were quartered could be made good:

Well, to make amends for these injuries, I hope after our war we shall erect a noble national university at which the youth of all the world may be proud to receive instructions.

In the establishment of the Federal City, in which Blodget had a hand. Washington clearly intended there be a national university established; although he acknowledged it “may be properly deferred until Congress is comfortably accommodated and the city has so far grown as to be prepared for it, the enterprise must not be forgotten….” A number of members of the Constitutional Convention wanted provision for the university, “in which no preference or distinction should be allowed on account of religion,” to be included in the Constitution. It was omitted, in the end, not because a national university was not desired, but because a number of states felt the provision to be superfluous, and that it was clear the government had the power to create such an institution. (All this detail and vastly more can be found in John W. Hoyt’s “Memorial in Regard to a National University.”) In presidency after presidency, the issue was raised, without action. The issue faded and then, Hoyt says, rose again after 1849, when “something was done toward founding a national university at Albany, New York.”

The subject appears to have been first publicly broached at Albany by Henry J. Raymond, in the State legislature of 1849. Finally, by agreement between leading educators, scholars, scientists, and statesmen, in the year 1851 a preliminary arrangement was made for the organization of a university of the highest type, as the same was then apprehended, and in accordance with the following governing principles:

[1] The concentration of the ablest possible teaching force for each and all the departments of human learning.

[2] The utmost freedom of students to pursue any preferred branch or branches of study.

[3] Support by the State, for a period of two years, of one student from each assembly district, to be chosen by means of open competitive examinations, so conducted by competent examiners as to exclude all considerations but that of real merit; such public support to be had, however, only after at least fifteen departments had been so endowed as to command the best professional talent the country could afford.

The movement awakened so much interest among distinguished educators that conditional engagements are said to have been made with such men as Profs. [Louis] Agassiz, [Benjamin] Peirce, [Arnold] Guyot, [James] Hall, [Ormsby M.] Mitchell, and [James Dwight] Dana.

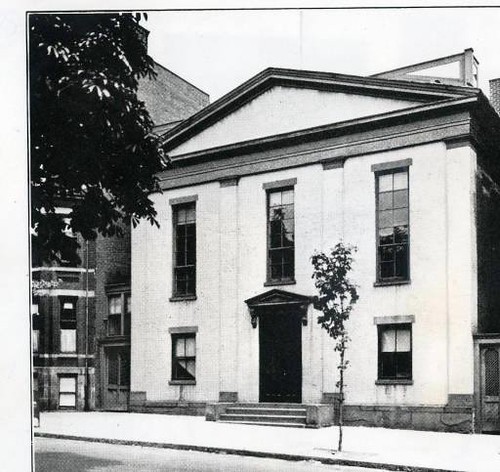

The result was an act, passed April 17, 1851, incorporating the University of Albany. Forty-eight city residents were named as trustees, empowered to create departments of medicine and law, and others as might be deemed desirable. The law school was organized that month, with Thomas W. Olcott as president of the board of trustees, and the first course of lectures begun in December 1851 by Amos Dean. This, of course, became Albany Law School, which merged into Union University in 1873.

A department of scientific agriculture was established, in which would be lectures on geology, entomology, chemistry and practical agriculture. A course on the connection of science and agriculture was begun in January 1852 by Prof. John F. Norton of Yale College. Prof. James Hall and Dr. Goodly also lectured.

In March 1852 came a further clamor (some of which we read about yesterday) for the establishment of the national university at Albany, with meetings in the Assembly chamber on March 10, 11 and 12 of that year, and much, much speechifying. Out of it all came the Dudley Observatory, which Hoyt described as the third institution inaugurated as part of the proposed national university, though it is less than clear if the agricultural arm was still functioning by the time the observatory sort of opened in 1856. At its inauguration, many spoke of the need to establish a great national university, though by that time none of the speakers seemed to be suggesting that these three-ish institutions in Albany were it, and one went so far as to say that “in order to be national it should be located upon common ground. Under existing circumstances it would be wholly impracticable in New York, or Alabama, or anywhere outside the District of Columbia.” He suggested the states have a role in both governing and paying for the institution.

Eventually, the Dudley Observatory, Albany Law School, and Albany Medical College (which predated the legislative call for such a school) would all become part of the loose federation known as Union University, created in 1873. The State Normal School became the NYS College for Teachers, which in 1962 finally fulfilled the promise of a university in Albany with the creation of the State University of New York at Albany.

Whether the legislation that originally constituted the University of Albany was ever amended or repealed, we have not determined. But it was more real than a national university ever was.

Leave a Reply