In the middle of the 19th century, the highly respected scientific advisor to Albany’s nascent observatory went on a spending spree of epic proportions. Even in Albany, rarely has so much been spent for so little result. That even some of what was purchased was eventually actually acquired and put into use should be considered something of a miracle. As we previously noted, the Dudley Observatory was inaugurated without any of its telescopes, clocks, or scientific instrumentation in place, and some of that equipment never came to fruition. But it did get some heavy stone piers, the fanciest iron shutters for the dome, and one of the earliest computers in the world, which was apparently never put to any use.

On the Observatory’s Scientific Council were Dr. Benjamin Apthorp Gould and Alexander Bache, one of the leading men of science of his day and head of the Coast Survey. Bache championed the opinions of Dr. Gould and pressed for him to be named director of the Dudley. Bache wrote “Now that matters have gone so far at Albany, why not . . . consult Dr. Gould about all the details? I would not now move a peg without his advice.”

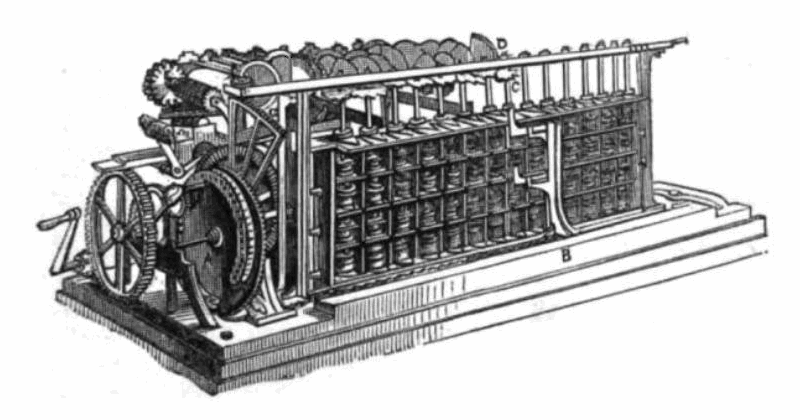

The Trustees were nevertheless souring on the promises of Gould. with little to show for many thousands of dollars in spending. And then there was the question of buying a computer.

About this time [1856], Dr. Gould urged the Trustees to purchase a calculating machine of the achievements of which he had spoken very enthusiastically. Neither Transit, Meridian circle, Chronographs, Clocks or Dials, in all of which large investments had been already made, were received, and nothing was in working order. Great as was their respect for science, and entire as was their confidence in their scientific advisers, they could not always repress the regret and disappointment they felt, that, as yet, so little that was visible or practical, had been accomplished. Still, they retained their confidence in Dr. Gould, and gave their consent that he should purchase “the calculating machine,” although the funds of the Observatory scarcely justified the expense . . .

The Trustees will not attempt to justify themselves for permitting an expenditure, so obviously injudicious. The “machine” had been exhibited and held for sale, both in Paris and in London, without finding a purchaser. Its utility had yet to be demonstrated. Not another Observatory in the world had ventured to invest the amount required, in such an experiment . . . The “machine” was purchased in December, at a cost of five thousand dollars. It arrived in April, 1857, but was laid aside for more than twelve months, when it brought forth a column of printed figures, and the Trustees were charged two hundred dollars for “bringing it into use.”

There is only one reference in the Trustees’ statement on the matter that positively identifies this calculator – it was a device created by Per Georg and Edvard Scheutz of Sweden, based on Babbage’s difference engine. Wikipedia mentions that Georg Scheutz created two of these machines, one sold to the British government in 1859 and another to the United States in 1860; but Gould in one of his letters in 1858 clearly refers to it: “the Observatory possesses the Calculating or Tabulating machine of G. and E. Sheutz, of Stockholm, which is still unpacked.” Wikipedia describes the devices as being used to create logarithmic tables, but notes that it was imperfect and did not produce complete tables. It was never clear what it was intended to accomplish in astronomical calculation.

That was hardly the final indignity the Trustees suffered. There was the matter of the piers, the supports for the telescopic instruments.

“Dr. Gould desired to have the largest solid stone piers in the world; irrespective of cost; and the Trustees, relying upon him as a practical astronomer, were anxious to second his views. It is true, they sometimes considered those views peculiar.” For instance, Dr. Gould’s insistence meant that the front wall of the Circle Meridian room “was necessarily kept open during the whole winter, in consequence of Dr. Gould’s objections to the piers from the Lockport quarries, and the time occupied in procuring others from Kingston.” Further, he insisted on the development of a crane of his own design for the placement of the piers, and the use of this crane required that the walls of the west wing be taken down and then rebuilt.

The Trustees, ignorant as they are, are not so ignorant as not to know that great precision is necessary in placing such piers. But they also suppose that to move them to their place and elevate them, is a very simple and easy matter. A competent mechanic could do it all. But, to have a stone, which was to be devoted to such a purpose, moved and handled like common stones, would not suit the notions of Dr. Gould. He must have a crane contrived specially for this purpose.

That involved engineering, lots of back and forth of plans and, of course, much expense. He also insisted on iron shutters for the wooden dome and the wings. The shutters, if made of wood, were expected to cost $300, and go on a wooden dome that cost $3000.

In 1857, in the midst of the financial troubles of the country, Dr. Gould directed the architect to prepare plans for flexible iron shutters – a thing, as the Trustees understand, unknown in any Observatory in the world. The plan has been executed. The shutters have been made, and now they are too heavy for the dome. A new dome must be built, at a cost of $3000 or more, or else the shutters, which, with the machinery for opening and closing them, cost nearly $2000, must be lost. Dr. Gould also caused expensive machinery to be constructed for opening the shutters of the wings. The practical loss to the Observatory, arising from these injudicious expenditures, is probably not less than $5000.

The Trustees expressed the end of their patience to the Scientific Council in June of 1858, and believed that Council would advise Dr. Gould “to retire from his position, and, if they chose to be further connected with the Observatory, suggest some suitable person to succeed him.” Instead, Gould and the Council put up a fight, enlisting Mrs. Dudley, the original benefactor, to their side. Found, unusually, at the Observatory, Gould employed a guard to prevent the Trustees from entering the facility; he was finally run out by a court order and police escort.

Happily, Dr. O. M.Mitchel, the Trustees’ first choice, was now able to accept the position of director, and although he was still unable to relocate to Albany, he sent an associate director, Franz Brünnow, who was more than capable. Under their guidance, the Dudley finally became ready to make astronomical observations.

(The Trustees, by the way, were the following: Thomas W. Olcott, Ira Harris, Robert H. Pruyn, William H. DeWitt, Jonathan F. Rathbone, James H. Armsby, Samuel H. Ransom, Alden March, and Isaac W. Vosburgh.)

Pictured is rawing of the Difference Engine No. 1 designed by Pehr Georg Scheutz and his son Edvard Scheutz from 1843 onward. The machine was completed in 1853 conjunction with Johan Wilhelm Bergström. F

Leave a Reply