So as we noted previously, the original Dudley Observatory, located on Dudley Heights in Arbor Hill in Albany, was created in a fit of local scientific boosterism that took advantage of the fact that Blandina Dudley had wads of her deceased husband’s cash, a wish to have him memorialized, and apparently couldn’t say no to the Trustees of this new institution, who went to the well repeatedly. Originally conceived and organized from 1851-53, the institution was inaugurated on August 28th, 1856, with a special meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. One would expect that would have been a tremendous occasion to show off the beautiful new observatory building, the various clocks and chronometers so vital to the study of celestial objects, and the Olcott Meridian Circle that was named for benefactor and trustee Thomas Olcott, which would precisely pinpoint objects in the night sky. What a proud night that would have been! But at the inauguration, none of the instruments had yet been received, the walls of the institution were unfinished (waiting for the large instruments to be put in place), and the entire ceremony took place over at the Capitol, a healthy distance from where the Observatory wasn’t yet.

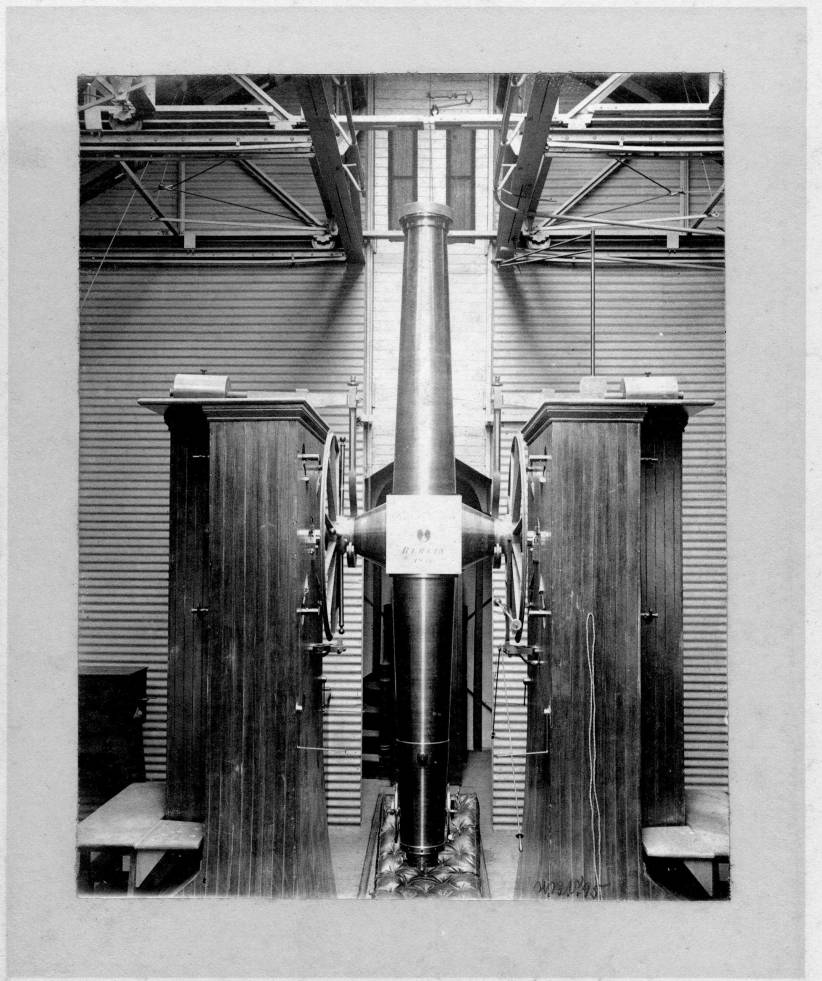

In 1858, the Trustees of the Observatory felt compelled to issue a statement, one of many in an unusual back-and-forth between the Trustees and the director/advisor of the Dudley, Benjamin Apthorp Gould. When their first choice to guide the observatory, O.M. Mitchel of Cincinnati, could not be available in Albany on their timetable, the Trustees turned to Dr. Gould, the first American to receive a Ph.D. in astronomy. He became introduced to the Dudley project when the Trustees looked at making a business arrangement with the Coast Survey, a Naval operation that was prohibited from establishing a fixed observatory. The survey’s superintendent, Doctor Bache, suggested that Albany obtain a heliometer, by means of which “certain astronomical measurements can be performed with greater accuracy, than by any other instrument at present known to science.” The Coast Survey was very much interested in access to such an instrument. Bache said that if the citizens of Albany should purchase a heliometer, the Coast Survey would supply a transit instrument and observers free to the institution. The Trustees went to Mrs. Dudley, secured $6000 for a heliometer, and went back to Bache. Bache and others asked for the creation of a scientific advisory council, on which both Bache and Dr. Gould, among others, would sit.

In the meantime, Mrs. Dudley was hit up for another $8,000 so that the “Heliometer might be the largest and best instrument of its kind in the world.” Olcott ponied up the money for his Meridian Circle (at a mere $5,000), and Bache authorized the purchase of a transit instrument. There was also to be a “Normal Clock,” a highly precise instrument that was to be funded in part by railroad magnate Erastus Corning. With this shopping list and a letter of credit, Dr. Gould was sent off to Europe in late 1855 to make the necessary arrangements for these vital instruments, which were to be constructed and in place by August 1856. Returning from Europe, Gould brought back the idea that the observatory would provide the New York Central Railroad with accurate time, determined by the observatory and indicated telegraphically to the railroad, at a rate of $1500 a year. Similar offers were made to other railroads, and to several cities including New York City. Writing to the mayor of New York City, Gould said that when the time service began in August 1856, it would “give accurate time to your city, within the fraction of a second, by the dropping of a time ball.”

Just two years after this promise, the Trustees expressed some bitterness, saying they, “in their simplicity, believed all this meant something. They believed that Dr. Gould had a perfect knowledge of all the facts; they thought that he, if any one, knew what instruments he had ordered were capable of accomplishing, and when they could go into operation. They believed that these visions were soon to become realities, and that from and after the time of the Inauguration, the trains on every railroad centering in Albany would govern their movements, and start from every station, by the click of the ‘Corning Clock;’ and that when, in the eloquent language of the immortal Everett, ‘the eternal sun strikes twelve at noon, and the glorious constellations, far up in the everlasting belfries of the skies, chime twelve at midnight’ – then, the dropping time ball in every great city on the continent would announce at so many points on earth, what was thus chimed in the ‘belfries of the skies.’” The Trustees had been promised this would be a tremendous revenue stream.

“The effect of these brilliant prospects was, as might be supposed, greatly to increase the confidence of the Trustees in their adviser.“

There was the matter of the heliometer. Gould had not contracted for one in Europe, and instead proposed that one be built by a Mr. Spencer of Canastota; not only did the price increase, but it was asked that the Trustees send Spencer to Europe to examine other heliometers. The Trustees assented. Then Gould suggested that another person be sent with this Spencer, arguing that Spencer was unused to travel, that his life was too precious to the cause of science to be risked, and that he bore certain peculiarities; “a judicious companion might, to use his own language, ‘prevent him from going off upon side issues.’” This the Trustees also finally agreed to. More things were bought, or at least ordered, and Dr. Gould was working from Cambridge, MA, his home, or travelling; he was rarely in Albany. He blamed others for problems with construction, though it was clear he was holding things up, delaying design of the piers needed to hold the telescopes and the designs needed for the time ball system. . He promised that the Meridian Circle would be shipped by the end of July, 1856, but found there was going to be trouble with the chronographs. Time, somewhat ironically, ran out. The Trustees wrote:

The Inauguration was to take place on the 28th of August. It was to occur at the time of the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and to constitute its great feature of attraction. To it, the Trustees had looked forward with intense interest. It brought with it, it is true, some reasons for sadness. It came with hopes unfulfilled, and expectations disappointed. Of all the splendid promises made by Dr. Gould, and the brilliant visions which he had kept before their eyes, not a single one was realized. No Transit, no Meridian Circle, nor any other instrument attracted the admiration of the scientific world. No marvelously constructed clock, noiselessly recorded the accurate passage of time, as it was chimed forth from the “belfries of the skies.” No “time ball” fell in the great commercial emporium. No bond of ever acting sympathy, linked together the clocks of Rochester, Buffalo, Troy and Albany. No railroad station exhibited to the scientific members, on their way, any evidence that the trains upon which they traveled, were deriving their time from the Dudley Observatory. The Observatory itself had the appearance of a ruin. The walls of both wings were open to receive the piers and cap-stones, and to permit the working of the “Ingenious Crane,” or as it might more properly be called, the Automaton Mason. Instead of leading their distinguished visitors up the hill, to spread before them the glories of the model instruments, the efforts of the Trustees were directed towards keeping them within the limits of the capitol, and the large tent, and inducing them to forget the deficiency of the real, in the brilliancy of the fanciful.

Leave a Reply