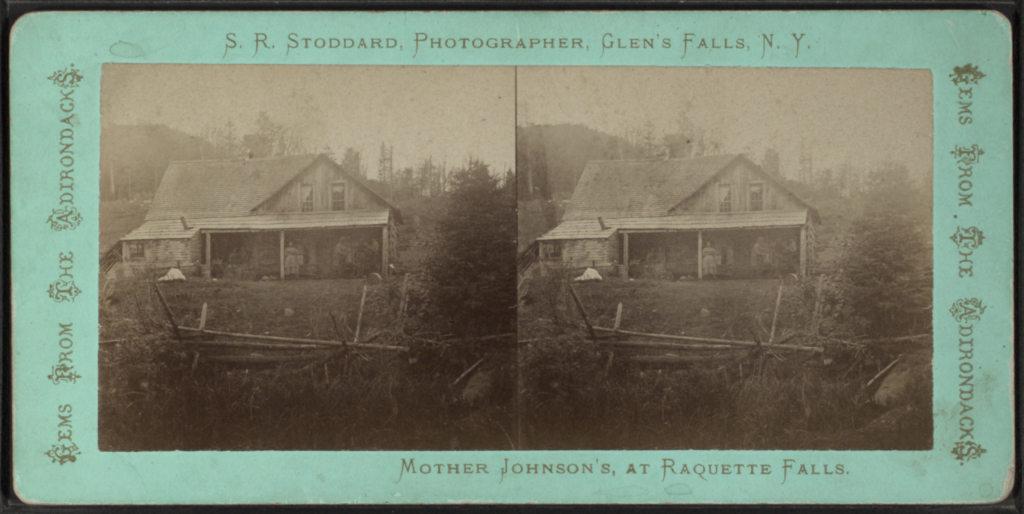

While we’re on a little bit of family history, here’s a bit more: my great great great grandmother was “Mother Johnson,” famed supplier of pancakes to the likes of Rev. W.H.H. Murray and Seneca Ray Stoddard. Along with husband Philander Johnson, she ran a lodge on the Raquette River at Raquette Falls starting in the 1860s; it was a popular stopping-off point for local guides and their big-city swells who were just then making wilderness a destination. This stereophotograph by Stoddard likely shows Mother Johnson next to the center post.

She was born about 1812 as Lucy Kimbol (or Kimball – spelling was loose in those days). She married Philander Johnson, who was about five years older, and they lived in Moriah in eastern Essex County. They moved to Crown Point, where other parts of the Johnson family and other related families resided, and then went inland to Newcomb some time before 1855. They appear to have had at least two children, and possibly four. One was William K. Johnson, whose Civil War service was mentioned yesterday. Then, sometime around or after 1860, they moved deeper into the wilderness, to Raquette Falls in what was then Brandon in Franklin County; now it’s part of Harrietstown.

We don’t know exactly when Lucy Kimbol Johnson, my great great great grandmother, became the “Mother” Johnson of Adirondack fame, known for her pancakes and her hospitality in the middle of what was then some pretty remote wilderness at Raquette Falls; some reports say 1860, some say after the Civil War. We don’t know why her husband Philander isn’t mentioned by name in any of the accounts of her lodge, inn, or house, however it might be described, though he is mentioned as “Uncle” Johnson. We don’t get much of a description of what she provided other than pancakes and fish that may have been trout, and and we know that Uncle did some boat dragging and portaged luggage with oxen. But her place on the Raquette River was considered a must-visit by several of the writers who made the Adirondacks famous, including Edwin R. Wallace, Rev. William Henry Harrison Murray, and Seneca Ray Stoddard. It was Murray who first mentioned her and apparently started a stream of visitors to her house.

W.H.H. Murray wrote a book titled “Adventures in the Wilderness: Camp-life in the Adirondacks,” published in 1869. This was one of the earliest guidebooks for city folks looking to get away to the wilderness, and in it Murray provides every particular of how to get there, including where to make rail connections and which hotels to write to in order to make arrangements. It was all very complicated, and the roads were very bad at the time. Hardly anyone lived in this region, which was of course part of the attraction; those few who did ran hotels or worked as guides. There’s hardly a prominent innkeeper or guide in the Saranac/Raquette region that this family isn’t connected to in one way or another. This is what Murray wrote about Mother Johnson’s in his listing of hotels:

“Mother Johnson’s.” – This is a “half-way house.” It is at the lower end of the carry, below Long Lake. Never pass it without dropping in. Here it is that you find such pancakes as are rarely met with. Here, in a log-house, hospitality can be found such as might shame many a city mansion. Never shall I forget the meal that John and I ate one night at that pine table. We broke camp at 8 A.M., and reached Mother Johnson’s at 11.45 P.M., having eaten nothing but a hasty lunch on the way. Stumbling up to the door amid a chorus of noises, such as only a kennel of hounds can send forth, we aroused the venerable couple, and at 1 A.M. sat down to a meal whose quantity and quality are worthy of tradition. Now, most housekeepers would have grumbled at being summoned to entertain travellers at such an unseasonable hour. Not so with Mother Johnson. Bless her soul, how her fat, good-natured face glowed with delight as she saw us empty those dishes! How her countenance shone and side shook with laughter as she passed the smoking, russet-colored cakes from her griddle to our only half-emptied plates. For some time it was a close race, and victory trembled in the balance; but at last John and I surrendered, and, dropping our knives and forks, and shoving back our chairs, we cried, in the language of another on the eve of a direr conflict, “Hold, enough!” and the good old lady, still happy and radiant, laid down her ladle and retired from her benevolent labor to her slumbers. Never go by Mother Johnson’s without tasting her pancakes, and, when you leave, leave her with an extra dollar.

So we have a mention of Mother Johnson and even of her husband, whose name is given in none of these accounts. Seneca Ray Stoddard, in his “The Adirondacks: Illustrated” from 1874, also mentions Mother Johnson:

Mother Johnson’s is on the Raquette, seven miles above Stony Creek. All admirers of the Rev. W.H.H. Murray, and readers of his romantic and perilous adventures in the Adirondacks, will remember his struggle with the pancakes, and Mother Johnson is the one who had the honor of providing them. We reached the house at noon, and the good-natured old lady got up a splendid dinner for us; venison that had (contrary to the usual dish set before us) a juiciness and actual taste to it. Then she had a fine fish on the table.

“What kind of fish is that, Mrs. Johnson,” I inquired.

“Well,” said she, “they don’t have no name after the 15th of September. They are a good deal like trout, but it’s against the law to catch trout after the fifteenth, you know.”

Mother Johnson moved here with her husband in 1870, and they pick up a good many dollars during the season from travelers, who seldom pass without getting at least one meal. Boats are dragged over the [Raquette Falls] carry nearly two miles in extent, and a very rough road at that, on an ox sled, at a cost of $1.50. A few rods above the house is Raquette Falls, laying claim to the honor of being Mr. Murray’s “Phantom Falls.” The actual fall here is probably not over twelve or fifteen feet. Mother Johnson entertains a very exalted opinion of Mr. Murray, with good reason, too, as his Adirondack book first turned the tide of travel past her door, and was the means of converting her pancakes (we had some) into greenbacks; and although she may subscribe heartily to the belief that “man was created a little lower than the angels,” it is no more than natural that she should make an exception in the case of the Nimrodish divine alluded to [meaning Murray].”

Stoddard also writes a fanciful, outlandish, absurd history of the Battle of Plattsburgh (citing for instance that the attacking squadron, under Commodore Columbus, included the Santa Maria Smitha and the Mayflower) in which he namechecks Mother Johnson, 19th century style:

Soon other reinforcements began to arrive. Fred Averill’s dragoons came in Harper & Tuft’s four-horse coaches. Kellogg advanced from Long Lake, and Martin came Moodily over from Tuppers. Old Mountain Phelps slid down into the enemy, creating a panic in the commissary department; while Mother Johnson turned such a fierce fire of hot pancakes toward them that they fell back in confusion, and when Bill Nye arrived with his mounted Amazons, they fled totally routed seeing which, the attacking fleet withdrew, badly riddled, the commodore’s ship to discover America, the Mayflower only floating long enough to land its commander on Plymouth Rock, where he climbed into the gubernatorial chair and remained there until he was translated in a chariot of fire – which way the historian fails to state.

Edwin R. Wallace’s “Descriptive Guide to the Adirondacks,” 1876, says that Mother Johnson died in January 1875, “but the house will probably be continued as a hotel,” and provides us with a drawing of the house which appears to be taken from a photograph by Seneca Ray Stoddard:

His text must have been written before his appendix, for the text says,

“At Raquette Falls, ‘Mother Johnson’s famous pancakes’ may be procured, and ‘Uncle’ Johnson may be employed to transport baggage over the portage with his oxen, for which he charges $1.50 per load. The house is a sort of blocked log concern, pleasantly overlooking the river. The falls, ¼ mile distant, are very pretty and romantic, and are entitled to all the notice they receive. . . A “blazed” line extending 3 m westerly from “Hotel de Johnson,” terminates at Folingsby’s [sic] Pond, to which the water distance is 12½ m.”

By the way, meals at Mother Johnson’s were listed by Wallace as being 50 cents, or $1.50 for the day, $7.00 per week. By comparison, the nearby Dukett & Farmers’s lodge at Spectacle Ponds (where Lucy Johnson’s daughter Sylvia likely lived) charged 50 cents, $2.00 for the day, or $12.00 for the week, the same rate as Corey’s near Upper Saranac Lake. At this time, train fare from New York City to one of the Adirondack stations cost from $5 to $8. At the time, a blacksmith might have earned $18 a week (for 60 hours), a laborer somewhat less than $10. So these provisions were not on the cheap side, but all food probably had to be brought in from Newcomb and likely well beyond, so the cost was likely very high.

Christopher Angus, in his “The Extraordinary Adirondack Journey of Clarence Petty: Wilderness Guide,” says that:

Predating even these hearty timbermen was a woman by the name of Lucy Johnson. A former lumber camp cook from Newcomb, Mother Johnson, as she was called, took up residence at Raquette Falls around 1860 with her husband, Philander. Even at this early date, the secluded spot was a natural location for the distribution of supplies to lumbermen working high on the slopes of the Seward Range.

Mother Johnson remained at the site for many years as a revered cook and innkeeper, and her legendary pancakes were immortalized in Adirondack Murray’s book. After her death during the winter of 1875, a hermit by the name of Harney snowshoed ten miles to Hiawatha Lodge [which her daughter and son-in-law Sylvia and Clark Farmer owned] to arrange for a coffin for her burial. She was supposedly buried at the foot of the cascade, but there is no sign of her grave. Christine Jerome, author of An Adirondack Passage: The Cruise of the Canoe “Sairy Gamp, notes that a marker bearing the name Lucy Johnson stands among other stones of the same era in the Long Lake Cemetery. The tradition Mother Johnson began of providing lodging at Raquette Falls continued for nearly half a century beyond her death.

Hiawatha House was Dukett’s place on Stony Creek Ponds. Harney the hermit was Harney Frenia, who was listed as living with Philander Johnson in 1875. The Duketts were the house next door, though next door may have been about seven miles down the Raquette and some ponds away. Christine Jerome, in recounting the adventures of George Washington Sears, better known as the Adirondack writer Nessmuk, says that at places like Mother Johnson’s, out-of-season deer was identified on the menu as “mountain lamb.” This is certainly taking liberties, as it is extremely unlikely Mother Johnson’s had a menu.

Jerome also writes that:

Although she had asked to be buried in Long Lake, her request had to be deferred in the face of January realities: a frozen river, thigh-high snowdrifts, and miles of forest in every direction. The burial itself proved difficult enough. Harney had to snowshoe ten miles to find someone who could make a coffin, and then several miles farther to get the lumber. In the meantime a shallow grave was hacked out of the frozen earth on a knoll behind the inn. There was no real ceremony; besides the family only three mourners were present. The plan was to move her remains in the spring, when the river opened.

A mystery attends the final disposition of Lucy Johnson’s remains. Some historians believe she still lies beneath her knoll, but there is no trace of her grave at the falls. There is, however, a marker in the Long Lake cemetery bearing her name, and it stands among other stones dating back to her era. (Her headstone is a curious affair. On one end of the small slab someone chiseled “Old Mrs. Johnson” and then thought better of it, turned it upside down, and chiseled “Mother Johnson.” The original inscription is still visible at the grass line.) A married daughter [likely Sylvia Farmer] ran the place for a while, and for the next forty-odd years a succession of other innkeepers came and went, although the house continued to be known as Johnson’s.

Jerome goes on to say it became a residence after WWI, owned by a New York City lawyer named George Morgan, who died in 1944 and was buried on a knoll nearby; and that the final inhabitant was Charles Bryan, former president of the Pullman railroad car company After his death the state acquired the land.

A Sept. 12, 1973 newspaper article in the Tupper Lake Free Press Herald tells the story a little differently. It recounts a fire that destroyed the Raquette Falls lodge, which had been built on the site of Mother Johnson’s. It said that Charles DeLancett of Tupper Lake built a lodge there in 1910, which burned and was replaced by a new lodge by George Morgan, who died there in 1944. The article says that Philander and Lucy A. Johnson came in from Newcomb “shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War and built a crude log house in a clearing off the river, below the falls. There they catered to the needs of the passing sportsmen, trappers and loggers for food and shelter and there, on January 27, 1875, ‘Mother’ Johnson died. To get boards for a coffin it was necessary for Harney, a hired hand who had driven the oxen to haul boats around the carry for the Johnsons, to hike down river to Indian Carry and on out to Bartlett’s, between Upper and Middle Saranac Lake. ‘Mother’ Johnson was buried on the knoll behind the original log cabin, where a bronze plaque set in a rock now marks her resting place. Philander Johnson gave up his lonely wilderness hostelry soon after his wife’s death, leaving the area in 1876.”

In addition to all these remembrances from now-famous writers, we do have a small bit of remembrance from a family member. Sylvia Johnson Farmer’s daughter, Jennie Farmer Morehouse, wrote to the Tupper Lake Free Press in 1938. The paper incorporated her letter into a general remembrance of Mother Johnson:

The reason for this item lies in a letter received at the Free Press from a direct descendant of that grand old character – Mrs. Jennie Morehouse of Indian Lake, great-granddaughter [incorrect: she was the granddaughter] of Mother Johnson. Mrs. Morehouse is 63 years of age, and she recalls many a colorful incident from her childhood at Axton. Her father, she says, shot several panthers in that sector in the early days. His grave, and those of her grandfather and grandmother, are at Raquette Falls, where stands the old Johnson barn – more than 80 years old, and put together, in pioneer fashion, with wooden pegs instead of nails. Nails were a rare and expensive commodity in the North Woods in the middle of the 19th century.

“My father’s name was Clark Farmer; my mother was Sylvia M. Johnson,” Mrs. Morehouse writes. “I was born at Axton. I had two cousins, Charley and George Johnson, who lived there 40 years ago – yes – 50. I wonder if the Johnson boys, or men, who go to Raquette Lodge would by any chance be Charley Johnson’s sons, or grandsons? George had no children. Charley’s oldest boy was named Leroy. I don’t recall the others; I was only 19, or around that, at the time.”

“I am 63 years old now, and my one desire is to see again the place where I spent my childhood,” Mrs. Morehouse writes. “That is why I am writing this letter. I want to take a trip to that dear old spot, and drop a line through between [sic] the logs of the old bridge where we used to cross the river on our way to Axton. I used to catch trout there with twine for fishline and a bent pin for a hook! I am wondering just how to get there – as we used to in the old days, by rowboat from Stony Creek, above Axton, or if there is a road so I can go by car. Please let me know if I should go in on the Wawbeek trail.”

With the passage of the half-century or more since Mrs. Morehouse lived there, it has become considerably easier to reach the old Johnson homesite near Raquette Falls, which lays claim to being the original “Phantom Falls” in the Rev. Murray’s exciting yarn. Today Mrs. Morehouse can travel by automobile from Indian Lake through Tupper Lake to Coreys – Axton, in her youth. A letter to George Morgan, proprietor of Raquette Falls Lodge, will undoubtedly result in arrangement to meet her near the Stony Creek bridge, and the remainder of the trip, about seven miles, must still be made by boat.

For the information of those of our readers who, like ourselves, arrived in the Adirondacks in a day when good highways and automobiles have replaced the guide-boat as a means of “getting places,” we can offer a little information about “Mother Johnson.” She moved, with her husband, to Raquette Falls in [illegible – 1860?]. Travel from Long Lake to Tupper was all by boat in those days, and it fell to Mother Johnson’s lot to feed the travelers, who invariably turned to her door while their boats were being dragged by ox-sled over the rough road around Raquette Falls carry. Mother Johnson became known far and wide for her pancakes, and many a man whose name was well-known throughout the country gratefully sampled her wares.

Mother Johnson died on January 27, 1875, after a short illness. Stoddard, in his volume “The Adirondacks,” printed in 1875, notes that “at the request of her husband, she was buried on a little knoll back of the house . . . the snow was so deep at the time as to make the way almost impassable, and but three, besides the family, were present at the time; but with their aid the body was laid away, with no ceremony save the sad good bye of those who loved her.”

Thanks to Jennie Morehouse’s letter, we have further confirmation that all these Johnsons were related; until uncovering a Civil War record wherein William directly named his parents, it was all hearsay and happenstance. The Charley and George she refers to as her cousins were Lucy’s grandchildren, William’s boys. They, too, became Adirondack guides. Charley did have a son named Leroy (or Lee Roy), and also had sons named Eugene, Guy and Jesse. Guy was my father’s father, so we get a little closer to the current generations.

After Lucy’s death, in 1880 Philander was living in Brandon very close to Charles and George Johnson, his grandsons (through William); his daughter Sylvia Farmer was living with him. He was also very close to John and Nancy Dukett, who ran a lodge at Corey’s, at the Indian Carry. Nancy was from the Graham family, which Philander’s son William married into. Nearly everyone in this part of the woods was related in some way; not too surprising considering how few people there were in that area.

So, uncharacteristically for the time, we know very little about Philander but at least a bit more about his wife Lucy. It appears that they had son William K. in 1830, and daughter Sylvia (Farmer) around 1836, in Moriah. There also appear to have been children named Betsy (1844) and Henry (1847); I haven’t done more to track the later children down, though Wallace (1876) mentions a Raquette River guide by the name of H.D. Johnson who could be reached through the Potsdam Post Office.

We finally got to visit the spot of earth where Mother and Philander set up their lodge – you can read about it here.

Leave a Reply