Just when brick manufacture began in New Netherlands has been the subject of considerable conjecture. It is often still taken as given that in the earliest days of settlement of the Hudson Valley, any brick that was used by the brick-loving Dutch settlers must have been imported, even though the cost to do so would have been astronomical and it seems unlikely any but the richest could have afforded to pay to have brick carried across the ocean in any meaningful quantities. A writer by the name of Robert W. Jones, writing in “Brick and Clay Record” back in 1917, said of the theory that bricks came over from Holland or England that “This interesting bit of fiction has been related so many times and so seldom disproved or questioned that it has come to be generally accepted as fact.” He argued that with the tremendous need for other manufactures, bringing brick across the ocean to a land so full of clay and fuel would have made little sense, and he made note of a letter from 1628 that said that in New Amsterdam, “They bake brick here but it is very poor.” He also said that in 1640 local yellow brick was being sold in Rensselaerswyck.

He did note however, an instance where brick was shipped. Arendt Van Curler, a founder of Schenectady, wrote to the patron in 1643 complaining that of 4,000 tiles and 30,000 hard bricks that were shipped from Holland, 2/3 of the bricks were kept by the ship’s captain as ballast, and that the tiles “crumble all away like sand . . . The broker who purchased the tile for your honor hath grossly cheated you.” The notation regarding ballast makes an excellent point, for it was often said that brick was brought over as useful ballast in these tiny sailing ships – but if they needed ballast coming to the new world, they certainly also needed it going back. Certainly some prominent homes were built of imported brick – Jones says that Crailo was among them.

Jones noted that a brickmaker was known to have come to New Amsterdam in 1653, and that there was notice that in 1657 Juffrouw (Miss) Johanna De Hulter had sold her steen bakkerij (brick kiln) to Adrian Van Ilpendam and her pannenbackerij (tile kiln) to Peter Mees. The Hoogeboom brothers were making tiles in Van Slechtenhorst’s kiln in 1658, and Pieter Jacobse Borseboom sold his brick kiln in 1662 when he moved to Schenectady. So it is pretty clear that early on there was a fair amount of brickmaking right in the Albany area.

In 1728, there was a little flood of applications to the Albany Common Council to establish new brick works. Luykas Hooghkerck applied to the Albany Common Council for two acres of land on Gallows Hill, for a term of fifty years, to be used in the manufacture of brick. (Gallows Hill appears to have been land to the south of Fort Frederick, running from Eagle down to South Pearl. Howell puts the cathedral squarely within Gallows Hill.) Jones reports that Hooghkerck was in the brick business for many years before and “this yard was never completely abandoned until about 1900.” According to the city records, Hooghkerck was granted that right for “twelf shillings,” provided that “he doth not stup op [stop up] ye Roods & passes at or near ye sd [said] ground nor the course of ye run of water.” “Roods” here meant “roads;” he couldn’t block the existing roads or paths. At exactly the same time, Abraham Vosburg applied for a 25 year lease for a brick kiln on two acres “upon ye Gallo hill adjouning at both side of a small run of water being by east of ye ground of Luykas Hoghkerck.” A third application was made by Wilhelmiss V.D. Bergh requested “to have ye use of a sartin small persell of ground lying to ye west of ye ground of ye heirs of Jan Gerritse, dec’d, on or near a creek or run of water which is said to be within ye limits of this corporation, for ye use of ye sd Wilhelmus & Nicolaes Groesbeeck to dig & prepare clay for bricks for ye term of six years.” Ten shillings for those rights to one acre of ground.

According to “A History of American Manufactures from 1608 to 1860,” by John Leander Bishop, “The clay banks in Lydius street (now Madison Avenue) for a long period supplied numerous brick-yards in the vicinity with material for their manufacture.” Bishop listed Hooghkerck’s among them, and said that in 1732 or 1733, the city “granted Lambert Radley and Jonathan Broocks an acre on gallohill, west of Hooghkerck’s brick-kiln, for twenty years.” They were charged 20 shillings for the privilege. Bishop also noted that Jan Masse had a brick-kiln in the western part of the city, south of Foxe’s Creek, in 1736, and Wynant Van der Bergh had one on the north side of the same creek (though I suspect Wynant was Wilhelmiss, mentioned above).

Jones also says that Jacobus Van Vorst’s bricks were used to build a parsonage in Schenectady in 1753, and that in 1736 Abraham Harpelse Van Deusen and Hendrick Gerritse Van Ness had a kiln on the north side of Foxen Creek.. He writes that “There are no records of these early times in which any mention is made of methods or manufacture except that the open yard was naturally the method of drying and to help cut the cost of production the school boys were allowed to ‘turn and spat’ for the privilege of swimming in the flooded clay pit. There are a few interesting records also of a method of tempering which was dependent upon a drove of cows being driven thru the prepared clay bed until the material was worked into a condition for molding.”

All of this was before significant brickmaking began over on the Beaver Kill, site of present-day Lincoln Park. William Moore began making bricks in Albany in 1844 (Howell, in his “Bi-centennial History of Albany,” notes that this came because his carting business was in decline.” He started at the head of Fourth Avenue, but with success moved to the corner of Morton and Hawk streets, where his son James succeeded him.

Howell also noted that George Stanwix started making bricks at Warren and Elizabeth streets in 1799; the business was passed down to his son and grandson, and the yard moved to Morton street in 1851. John Artcher made bricks sometime around 1840, starting on Chestnut Street, then on Jay, then on Hudson. Later on he moved to Western Avenue, where after 33 years in brickmaking he turned to brewing. James Smith and someone named Roberts made bricks at Morton and Eagle beginning in 1870. Capt. M.V.B. Wagoner made brick and slip clay at a yard his father established in 1845, bounded by Lark, Canal (Sheridan), Orange and Knox (Henry Johnson). Howell gave some other names without locations, including Edward Fisher, George Briant Basset, Ebenezer Wright, Patrick McCall, Alfred Hunter, Thomas McCarthy, Robert Marcelis and Joshua Babcock.

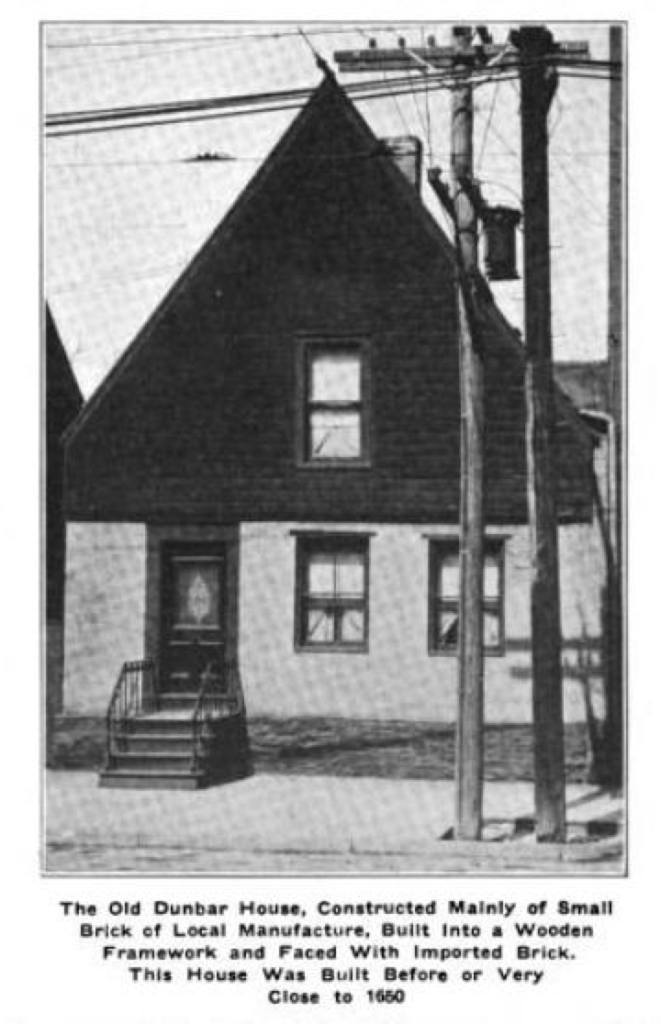

(Jones illustrated his story with a photograph of the “Old Dunbar House.” Presumably this was some relation to Robert Dunbar, the Patroon’s agent, but he didn’t give the location.)

Leave a Reply